Fairness and Equality in Electoral Redistributions in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Independents in Federal Parliament: a New Challenge Or a Passing Phase?

Independents in Federal Parliament: A new challenge or a passing phase? Jennifer Curtin1 Politics Program, School of Political and Social Inquiry Monash University, Melbourne, Australia. [email protected] “Politics just is the game played out by rival parties, and anyone who tries to play politics in some way entirely independent of parties consigns herself to irrelevance.” (Brennan, 1996: xv). The total dominance of Australia’s rival parties has altered since Brennan made this statement. By the time of the 2001 federal election, 29 registered political parties contested seats and while only the three traditional parties secured representation in the House of Representatives (Liberals, Nationals and Labor) three independents were also elected. So could we argue that the “game” has changed? While it is true that government in Australia, both federally and in the states and territories, almost always alternates between the Labor Party and the Liberal Party (the latter more often than not in coalition with the National Party), independent members have been a feature of the parliaments for many years, particularly at the state level (Costar and Curtin, 2004; Moon,1995). Over the last decade or so independents have often been key political players: for a time, they have held the balance of power in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory. More generally, since 1980 an unprecedented 56 independents have served in Australian parliaments. In 2003, 25 of them were still there. This is more than six times the number of independents elected in the 1970s. New South Wales has been the most productive jurisdiction during that time, with fourteen independent members, and Tasmania the least, with only one. -

Annual Report 2020 Facts and Trends 2019/20 2

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 FACTS AND TRENDS 2019/20 2 Import Coal Market at a Glance 2017 2018 2019 World Hard Coal Production Mill. t 6,852 7,064 7,257 World Hard Coal Trade Mill. t 1,267 1,324 1,336 of which seaborne hard coal trade Mill. t 1,157 1,208 1,221 of which internal hard coal trade Mill. t 110 116 115 Hard Coal Coke Production Mill. t 633 646 682 Hard Coal Coke World Trade Mill. t 26 28 26 European Union (28) Hard Coal Production Mill. TCE 81 76 67 Hard Coal Imports (incl. internal trade) Mill. t 172 166 134 Hard Coal Coke Imports Mill. t 9.1 9.0 9.5 Germany Hard Coal Use Mill. TCE 50.0 48.7 38.7 Hard Coal Volume Mill. TCE 51.6 47.1 37.9 of which import coal use Mill. TCE 47.9 44.4 37.9 of which domestic hard coal production Mill. TCE 3.7 2.7 0.0 Imports of Hard Coal and Hard Coal Coke Mill. t 51.4 47.0 42.2 of which steam coal 1) Mill. t 36.3 32.5 29.2 of which coking coal Mill. t 12.9 12.4 11.2 of which hard coal coke Mill. t 2.3 2.1 1.9 Prices Steam Coal Marker Price CIF NWE US$/TCE 98 108 72 Border-crossing Price Steam Coal €/TCE 92 95 79 CO2 emission rights (EEX EUA settlement price) EUR/EUA 5.83 15.82 24.84 Exchange rate (US$1 = €....) EUR/US$ 0.89 0.85 0.90 1) Including anthracite and briquettes Quelle: ??? 3 AN INTRODUCTORY WORD In 2020, it will be decided to end coal-fired power generation. -

Fflw Rilxxi /Fj~ :Mmw 56' University Road, Annandale, Qld 4814 P.O

The Federal Redistribution 2009 QUEENSLAND Objection Number 534 Colin White Chairman of the Board of Trustees The Good Shepherd Limited 3 pages 14:53 6747792693 , GOOD SHEPHERD HOME PAGE 0747792093 fflw rilXXi /fJ~ :mmw 56' University Road, Annandale, Qld 4814 P.O. Box 212, AitkeJ.lvale Qtd 4814 Telephone (07) 4777. 9900 Facsimile (07) 4779 2093 Website www.tg.•h.org.au Email admin~tR-.lh .org.au ABN 33 905 968 697 FACSIMILE MESSAGE To: AUSTRALIAN ELECTORAL COMMISSION Fax No: (07) 3834 3452 From: THE TRUSTEES OF THE GOOD SHEPHERD HOME LTD FAX No: 07 4779Z093 Date: 218T AUGUST Z009 n.lllf1M:Btna1k cordA111!1 conftdcnlW ~rol'll1llttOD ftMat b IIItMId.c1 for use 01111 by the••ftnOC!. [f70u MYe rHein. dIU t.e.tnriJc In CrMT, :tOU IlI'C M~ tllat copyJnr.lffdlllltnl! or otlleNile actin!!: In ftIillllee na au ftK:RImIll! is I!X]lJ'UlI3' proN1lltl!d. If>,"bau ftCdYeci tht~ dfMllllllmt 1D crror. pI-noW) at hmnedlat~."tcJephOIM or ftlallnOc,.4tMh either dacruy the fllClfmOt: or rtauna U to II!! ..,. posL Yoni' cfalm tor rdIIIb\meJlM!llt ofreullllallie cHtI to eompl1ill~lOlth tIla ..._ will be AtWIded to. Message: Attached is an official objectioD to the proposed redistribution ofthe seats ofBerbert and Dawson.. No. of pages following - 2 .~ G:\Office\ES\Templates\Fax.doc RECEIVED TIME 21. AUG. 15: 14 PRINT TIME 21. AUG. 15: 16 21/68/2009 14:53 0747792093 ! GOOD SHEPHERD HOME PAGE 62/133 0747792093 fflw riO«! [JJ~ut ~ 565 University Road, Annandale, Qld 4814 P.O. Box 2H, Altkenvale Qld 4814. -

Balance of Power Senate Projections, Spring 2018

Balance of power Senate projections, Spring 2018 The Australia Institute conducts a quarterly poll of Senate voting intention. Our analysis shows that major parties should expect the crossbench to remain large and diverse for the foreseeable future. Senate projections series, no. 2 Bill Browne November 2018 ABOUT THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE The Australia Institute is an independent public policy think tank based in Canberra. It is funded by donations from philanthropic trusts and individuals and commissioned research. We barrack for ideas, not political parties or candidates. Since its launch in 1994, the Institute has carried out highly influential research on a broad range of economic, social and environmental issues. OUR PHILOSOPHY As we begin the 21st century, new dilemmas confront our society and our planet. Unprecedented levels of consumption co-exist with extreme poverty. Through new technology we are more connected than we have ever been, yet civic engagement is declining. Environmental neglect continues despite heightened ecological awareness. A better balance is urgently needed. The Australia Institute’s directors, staff and supporters represent a broad range of views and priorities. What unites us is a belief that through a combination of research and creativity we can promote new solutions and ways of thinking. OUR PURPOSE – ‘RESEARCH THAT MATTERS’ The Institute publishes research that contributes to a more just, sustainable and peaceful society. Our goal is to gather, interpret and communicate evidence in order to both diagnose the problems we face and propose new solutions to tackle them. The Institute is wholly independent and not affiliated with any other organisation. Donations to its Research Fund are tax deductible for the donor. -

Proposed Redistribution of Victoria Into Electoral Divisions: April 2017

Proposed redistribution of Victoria into electoral divisions APRIL 2018 Report of the Redistribution Committee for Victoria Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 Feedback and enquiries Feedback on this report is welcome and should be directed to the contact officer. Contact officer National Redistributions Manager Roll Management and Community Engagement Branch Australian Electoral Commission 50 Marcus Clarke Street Canberra ACT 2600 Locked Bag 4007 Canberra ACT 2601 Telephone: 02 6271 4411 Fax: 02 6215 9999 Email: [email protected] AEC website www.aec.gov.au Accessible services Visit the AEC website for telephone interpreter services in other languages. Readers who are deaf or have a hearing or speech impairment can contact the AEC through the National Relay Service (NRS): – TTY users phone 133 677 and ask for 13 23 26 – Speak and Listen users phone 1300 555 727 and ask for 13 23 26 – Internet relay users connect to the NRS and ask for 13 23 26 ISBN: 978-1-921427-58-9 © Commonwealth of Australia 2018 © Victoria 2018 The report should be cited as Redistribution Committee for Victoria, Proposed redistribution of Victoria into electoral divisions. 18_0990 The Redistribution Committee for Victoria (the Redistribution Committee) has undertaken a proposed redistribution of Victoria. In developing the redistribution proposal, the Redistribution Committee has satisfied itself that the proposed electoral divisions meet the requirements of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (the Electoral Act). The Redistribution Committee commends its redistribution -

THE 'WA APPROACH' to NATIONAL PARTY SURVIVAL John Phillimore

This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Phillimore, J. and McMahon, L. 2015. Moving Beyond 100 Years: The "WA Approach" to National Party Survival. Australian Journal of Politics and History. 61 (1): pp. 37-52], which has been published in final form at http://doi.org/10.1111/ajph.12085. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving at http://olabout.wiley.com/WileyCDA/Section/id-820227.html#terms MOVING BEYOND 100 YEARS: THE ‘WA APPROACH’ TO NATIONAL PARTY SURVIVAL John Phillimore* Lance McMahon Submitted to and accepted by Australian Journal of Politics and History *Corresponding Author: [email protected] or 9266 2849 John Curtin Institute of Public Policy, Curtin University GPO Box U1987 Perth WA 6845 Professor John Phillimore is Executive Director of the John Curtin Institute of Public Policy, Curtin University. Lance McMahon is a Research Associate at the John Curtin Institute of Public Policy, Curtin University. June 2014 1 MOVING BEYOND 100 YEARS: THE ‘WA APPROACH’ TO NATIONAL PARTY SURVIVAL Abstract Since its formation in 1913, the Western Australian branch of the National Party has faced many challenges to its survival. Electoral reform removing rural malapportionment in 2005 prompted changes in strategic direction, including abandoning coalition with the Liberal Party and creating a discrete image, branding and policy approach. Holding the balance of power after the 2008 election, the Party adopted a post-election bargaining strategy to secure Ministries and funding for its ‘Royalties for Regions’ policy. This ‘WA approach’ is distinctive from amalgamation and coalition arrangements embraced elsewhere in Australia. -

Alan Mayne 2 Pages

Suggestion 161 Alan Mayne 2 pages South Australian secretariat Phone (08) 8237 6504 Fax (02) 6293 7663 Email [email protected] From: Alan Mayne Sent: Wednesday, 22 November 2017 2:30 PM To: FedRedistribution - SA Subject: Federal Seat Redistribution in South Australia Mayo: I submit below a general text that you will already have received from many Mayo electors, and which you may discount because it is based upon a shared template. However I want to emphasise here at the beginning that Mayo should not be abolished because the region it represents has historical, geographical, cultural and economic coherence and unity (AND ongoing vitality) which it would be foolish to unravel. At a time when this region is attracting world interest for its collective signature in premium-quality agricultural and viticultural production, and when its bid for UNESCO world heritage recognition is slowly gaining traction, it would be heart-rending to residents for the region to be removed from the nation's electoral map. The region would be reassigned to the margins of formal political activity (which is surely the antithesis of sensible planning for a healthy democracy?). I speak from the heart not only as a rural constituent of this complicated electoral mix of rural and city- fringe residents, but as a long-term volunteer member of the Oakbank-Balhannah CFS brigade. In the CFS (region 1) we give our all for this place, and I would expect that commitment to be considered seriously as you rework the federal electoral map of South Australia. To the Redistribution Committee for South Australia, I write to make suggestions to the South Australian Federal Redistribution currently being undertaken by the Australian Electoral Commission. -

Supplementary Agenda of Extraordinary Council

Mayoral Minute MM1 Extraordinary Meeting Venue: Administrative Headquarters Civic Place Katoomba Meeting: 7.30pm 2 June, 2015 - 2 - EXTRAORDINARY MEETING 2 JUNE 2015 AGENDA ITEM PAGE SUBJECT COMMENTS NO. MINUTE BY MAYOR MM1 4 Redistribution of Federal Electoral Boundaries in New South Wales - 3 - MINUTE BY MAYOR Item MM1, Ordinary Meeting, 02.06.15 ITEM NO: MM1 SUBJECT: REDISTRIBUTION OF FEDERAL ELECTORAL BOUNDARIES IN NEW SOUTH WALES FILE NO: F08771 - 15/99475 Delivery Program Link Principal Activity: Civic Leadership Service: Governance and Risk Recommendations: 1. That Council notes the Australian Electoral Commission is currently considering the boundaries of the Federal Electorate of Macquarie; 2. That the Council reaffirms its desire to keep the seat as closely aligned as possible with the Local Government Area, noting the tourism and economic significance of this region, including being a World Heritage area, which demonstrate a custodial responsibility for the Blue Mountains at all levels of government; and 3. That the Council writes to the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) under the signature of the Mayor asking for Macquarie to contain the whole of the Blue Mountains Local Government Area after any redistribution. Mayoral Minute Reason for report That Council notes the Australian Electoral Commission is currently considering the boundaries of the Federal Electorate of Macquarie. Consequently, Council resolves to write to the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) before the cut-off this coming Friday under the signature of the Mayor asking for Macquarie to contain the whole of the Blue Mountains Local Government Area after any redistribution. Background A redistribution of federal electoral boundaries in New South Wales is required following a determination on 13 November 2014 of the number of members of the House of Representatives to which each state and territory will be entitled at the next federal general election. -

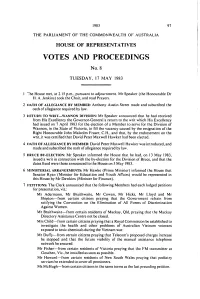

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 8 TUESDAY, 17 MAY 1983 1 "he House met, at 2.15 p.m., pursuant to adjournment. Mr Speaker (the Honourable Dr H. A. Jenkins) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2 OATH OF ALLEGIANCE BY MEMBER: Anthony Austin Street made and subscribed the oath of allegiance required by law. 3 IETURN TO WRIT-WANNON DIVISION: Mr Speaker announced that he had received from His Excellency the Governor-General a return to the writ which His Excellency had issued on 7 April 1983 for the election of a Member to serve for the Division of Wannon, in the State of Victoria, to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of the Right Honourable John Malcolm Fraser, C.H., and that, by the endorsement on the writ, it was certified that David Peter Maxwell Hawker had been elected. 4 OATH OF ALLEGIANCE BY MEMBER: David Peter Maxwell Hawker was introduced, and made and subscribed the oath of allegiance required by law. 5 BIRUCE BY-ELECTION: Mr Speaker informed the House that he had, on 13 May 1983, issued a writ in connection with the by-election for the Division of Bruce, and that the dates fixed were those announced to the House on 3 May 1983. 6 MINISTERIAL ARRANGEMENTS: Mr Hawke (Prime Minister) informed the House that Senator Ryan (Minister for Education and Youth Affairs) would be represented in this House by Mr Dawkins (Minister for Finance). 7 PETITIONS: The Clerk announced that the following Members had each lodged petitions for presentation, viz.: Mr Adermann, Mr Braithwaite, Mr Cowan, Mr Hicks, Mr Lloyd and Mr Shipton-from certain citizens praying that the Government refrain from ratifying the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. -

Practical Steps to Implementation of Integrated Marine Management Report of a Workshop, 13-15 April 2015

Practical steps to implementation of integrated marine management Report of a Workshop, 13-15 April 2015 Gavin A. Begg, Robert L. Stephenson, Tim Ward, Bronwyn M. Gillanders and Tony Smith SARDI Publication No. F2015/000465-1 SARDI Research Report Series No. 848 ISBN: 978-1-921563-80-5 FRDC PROJECT NO. F2008/328.21 SARDI Aquatic Sciences PO Box 120 Henley Beach SA 5022 July 2015 Final report for the Spencer Gulf Ecosystem and Development Initiative and the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation 1 Practical steps to implementation of integrated marine management Report of a Workshop, 13-15 April 2015 Final report for the Spencer Gulf Ecosystem and Development Initiative and the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation Gavin A. Begg, Robert L. Stephenson, Tim Ward, Bronwyn M. Gillanders and Tony Smith SARDI Publication No. F2015/000465-1 SARDI Research Report Series No. 848 ISBN: 978-1-921563-80-5 FRDC PROJECT NO. F2008/328.21 July 2015 ii © 2015 Fisheries Research and Development Corporation and South Australian Research and Development Institute All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-921563-80-5 Practical steps to implementation of integrated marine management. Final report for the Spencer Gulf Ecosystem and Development Initiative and the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation. F2008/328.21 2015 Ownership of Intellectual property rights Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this publication is owned by the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation and the South Australian Research and Development Institute. This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), no part may be reproduced by any process, electronic or otherwise, without the specific written permission of the copyright owner. -

ENG4111 Preliminary Report

University of Southern Queensland Faculty of Engineering and Surveying Own Identification of contributing factors for the success of toll roads in Australia under Public Private Partnerships A Dissertation submitted by Mr Luke Diffin In fulfilment of the requirements of Bachelor of Engineering (Civil) October 2015 ABSTRACT In Australia, Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) have been established as a common method for governments to deliver major road infrastructure projects. Success of PPPs has varied when measured against Government, Community, Market and Industry interests. Some projects have failed financially while still having a positive impact on the community. Other projects have failed to reach delivery stage as a result of community objections. The holistic success of PPP toll roads is ultimately determined by the needs of major project participants being satisfied in an unbiased equilibrium manner. PPP toll roads delivered in Sydney, Brisbane and Melbourne have had varying degrees of financial success, however there are other vitally important factors to be considered. Tollways directly contribute to travel time savings, vehicle operating cost savings, reduced accidents and vehicle emissions and can make a contribution to the overall economic performance of a city. Therefore these pieces of infrastructure contribute to society as a whole and not just the investors who provide capital for the projects. Even with recent financial failings of PPP toll roads, Governments within Australia are still actively pursuing the PPP model to deliver road infrastructure. Lessons must be learnt from past failures to ensure the successful delivery and operation of future projects. Overall success will be a result of finding a balance between the needs of Government, Private Sector and Society. -

July 2018 MAP of the FEDERAL ELECTORAL DIVISION OF

Macdonald Park Blakeview Penfield Andrews Farm Gardens Smithfield Virginia Penfield Davoren Uleybury Park Craigmore Yattalunga Waterloo Elizabeth JulyCorner 2018 North Elizabeth N Smith Downs k MAP OF THE FEDERAL Edinburgh Cree Buckland Park ELECTORAL DIVISION OF North Cr Elizabeth Park eek A One Tree Hill dams Humbug Scrub MAKIN Edinburgh Munno Para 0 2 km Direk Port Adelaide Elizabeth A D E L Elizabeth A ID East D E Name and boundary of R - HWY P O PLAYFORD Electoral Division W R A T Elizabeth TE Burton A R U Grove LO G O RD U SPENCE Gould Creek Names and boundaries of S P T I L G A I o k uld ree adjoining Electoral Divisions R H C C A O P RD Sampson Flat RN IL Hillbank E L Elizabeth Little Para R L IN Kersbrook St Kilda Reservoir L E Vale I Names and boundaries of Local H RD Government Areas (2016) Salisbury REE Paralowie North ittle r T BOLIVAR L Para Rive Salisbury D Hannaford Hump Rd Port Adelaide R Salisbury This map has been compiled by Spatial Vision from data supplied by the Australian Electoral S Park E Greenwith Commission, Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure, PSMA and Geoscience IT Heights E Australia. H Salisbury H N T O W Salisbury R T O HE Plain N r G Rive Salisbury Outer K R RD IN O G Downs FROST V Golden Grove Harbor S IN Salisbury Lower Bolivar E A E D Dry Creek N R I RD M East Hermitage locality boundary L Osborne IL TEA TREE GULLY Parafield A W a Salisbury r R RD Y a P Gardens South E R V E e E G tl RD O it L SALISBURY R Upper Hermitage A L W T Y G I Globe Derby A W H M Torrens Island Y G BRIDGE A - N