Cringe Comedy, Benign Masochism, and Not-So-Benign Violations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WDSG Keeping in Touch Newsletter, Issue 9

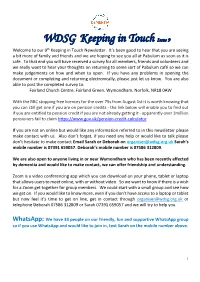

WDSG Keeping in Touch Issue 9 Welcome to our 9th Keeping in Touch Newsletter. It’s been good to hear that you are seeing a bit more of family and friends and we are hoping to see you all at Pabulum as soon as it is safe. To that end you will have received a survey for all members, friends and volunteers and we really want to hear your thoughts on returning to some sort of Pabulum café so we can make judgements on how and when to open. If you have any problems in opening the document or completing and returning electronically, please just let us know. You are also able to post the completed survey to: Fairland Church Centre, Fairland Green, Wymondham, Norfolk, NR18 0AW With the BBC stopping free licences for the over 75s from August 1st it is worth knowing that you can still get one if you are on pension credits - the link below will enable you to find out if you are entitled to pension credit if you are not already getting it - apparently over 1million pensioners fail to claim https://www.gov.uk/pension-credit-calculator If you are not on online but would like any information referred to in this newsletter please make contact with us. Also don’t forget, if you need any help or would like to talk please don’t hesitate to make contact Email Sarah or Deborah on [email protected] Sarah’s mobile number is 07391 659057. Deborah’s mobile number is 07586 312809. We are also open to anyone living in or near Wymondham who has been recently affected by dementia and would like to make contact, we can offer friendship and understanding. -

Statistical Yearbook 2019

STATISTICAL YEARBOOK 2019 Welcome to the 2019 BFI Statistical Yearbook. Compiled by the Research and Statistics Unit, this Yearbook presents the most comprehensive picture of film in the UK and the performance of British films abroad during 2018. This publication is one of the ways the BFI delivers on its commitment to evidence-based policy for film. We hope you enjoy this Yearbook and find it useful. 3 The BFI is the lead organisation for film in the UK. Founded in 1933, it is a registered charity governed by Royal Charter. In 2011, it was given additional responsibilities, becoming a Government arm’s-length body and distributor of Lottery funds for film, widening its strategic focus. The BFI now combines a cultural, creative and industrial role. The role brings together activities including the BFI National Archive, distribution, cultural programming, publishing and festivals with Lottery investment for film production, distribution, education, audience development, and market intelligence and research. The BFI Board of Governors is chaired by Josh Berger. We want to ensure that there are no barriers to accessing our publications. If you, or someone you know, would like a large print version of this report, please contact: Research and Statistics Unit British Film Institute 21 Stephen Street London W1T 1LN Email: [email protected] T: +44 (0)20 7173 3248 www.bfi.org.uk/statistics The British Film Institute is registered in England as a charity, number 287780. Registered address: 21 Stephen Street London W1T 1LN 4 Contents Film at the cinema -

Hist Art 3901 Course Change.Pdf

COURSE CHANGE REQUEST Last Updated: Haddad,Deborah Moore 3901 - Status: PENDING 12/31/2020 Term Information Effective Term Summer 2021 Previous Value Summer 2017 Course Change Information What change is being proposed? (If more than one, what changes are being proposed?) to offer a 100% distance learning offering of 3901 What is the rationale for the proposed change(s)? The course ran in AU20 during the pandemic and received a course assurance. The department would like the flexibility to run the course as a "DL" course in the future. What are the programmatic implications of the proposed change(s)? (e.g. program requirements to be added or removed, changes to be made in available resources, effect on other programs that use the course)? The department will be able to offer the course as "DL" during the summer (with college approval) and students who are off-campus during the summer will be able to take the course and further their degree requirements. The course is also a Film Studies major course option and it will help students in that program as well. Is approval of the requrest contingent upon the approval of other course or curricular program request? No Is this a request to withdraw the course? No General Information Course Bulletin Listing/Subject Area History of Art Fiscal Unit/Academic Org History of Art - D0235 College/Academic Group Arts and Sciences Level/Career Undergraduate Course Number/Catalog 3901 Course Title World Cinema Today Transcript Abbreviation World Cinema Course Description An introduction to the art of international cinema today, including its forms and varied content. -

SELF-CONSCIOUS EMOTIONS in AUTISM 1 Exploring the Subjective

SELF-CONSCIOUS EMOTIONS IN AUTISM 1 Exploring the subjective experience and neural correlAtes of self-conscious emotion processing in autistic adolescents: Over-reliAnce on leArned sociAl rules during heightened perspective- tAking demAnds mAy serve as compensAtory strategy for less reflexive mentAlizing KAthryn F. JAnkowski1 & Jennifer H. Pfeifer1 1 Department of Psychology, University of Oregon Corresponding author: Jennifer H. Pfeifer Department of Psychology University of Oregon 1227 University of Oregon Eugene, OR, 97403 541-346-1984 [email protected] SELF-CONSCIOUS EMOTIONS IN AUTISM 2 Abstract Autistic individuals experience a secondary wAve of sociAl cognitive challenges during Adolescence, which impact interpersonal success (Picci & Scherf, 2015). To better understAnd these challenges, we investigated the subjective experience and neural correlAtes of self- conscious emotion (SCE) processing in autistic adolescent mAles compared to age- And IQ- mAtched neurotypicAl (NT) adolescents (ages 11-17). Study I investigated group differences in SCE attributions (the ability to recognize SCEs) and empathic SCEs (the ability/tendency to feel empathic SCEs) and the potentiAl modulAtory role of heightened perspective-tAking (PT) demAnds. Furthermore, Study I explored associAtions between SCE processing, a triAd of sociAl cognitive abilities (self-AwAreness/introspection, perspective-tAking/cognitive empathy, and Affective empathy), and Autistic feAtures. Study II investigated group differences in neural Activation patterns recruited during SCE processing and the potentiAl modulAtory role of heightened PT demAnds. During an MRI scAn, participants completed the Self-Conscious Emotions TAsk (SCET), which feAtured sAlient, ecologicAl video clips of adolescents in a singing competition. Videos represented two factors: emotion (embarrassment, pride) and PT demAnds (low, high). In low PT clips, singers’ emotions mAtched the situational context (singing quality; sing poorly, act embarrassed); in high PT clips, they did not (sing well, act embarrassed). -

Folklore and Mythology of the British Isles

1 PIVOTAL WRITERS: DRYDEN, & BEHN (Eng479/579) Dr. Dianne Dugaw, [email protected] TTh 2:00-3:20, 276 Lokey Office: PLC 458, 346-1496 Off.Hrs.: T3:30-5:30; Th10-11; & appt. This course looks at two pivotal writers at a watershed moment in British literary history, 1650-1700: John Dryden, and Aphra Behn. Through the works of these wonderful literary artists, we will consider five key themes: the crisis of civil war and questions of monarchy and rule; the Catholic-Protestant divisions of Britain with their ideological, cultural, and ethnic implications; the new empirical science against the backdrop of world exploration and colonization; the emergence of mercantile capitalism; and changing conceptions of sexuality and gender, particularly as women took up literary expression. We will examine poetry, drama, and prose in the context of a rich and waning baroque sensibility that was giving way to a more ‘modern’ world. BOOKS: Aphra Behn, Oroonoko, The Rover & Other Works (Penguin, 2003); John Dryden, Selected Poems (Penguin, 2001), All for Love (Nick Hern, 1998), & Marriage-à-la-Mode (Norton, 2002); M.H. Abrams, Glossary of Literary Terms, 10th ed.(Thomson/Wadsworth, 2012). WORK: Midterm (25%); Take-Home Final (25%); In-Class Essays (25%); Presented Scene & Essay (25%) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- WK 1 (3/31): ‘Early Modern’: Looking Forward, Looking Back; Royalist & Puritan; Gender & Heroism T: Introduction: Books; the Course; 17th-Century Britain—Civil War, Restoration, & a transforming World Dryden, Venus’s Song, “Fairest isle &c.” (Canvas) & “Introduction,” Selected Poems pp.ix-xxiv. Th: Baroque Poetry: Behn, “Love Armed” (Oroonoko, the Rover, &c., p.329; also read intro. -

The Queer" Third Species": Tragicomedy in Contemporary

The Queer “Third Species”: Tragicomedy in Contemporary LGBTQ American Literature and Television A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences by Lindsey Kurz, B.A., M.A. March 2018 Committee Chair: Dr. Beth Ash Committee Members: Dr. Lisa Hogeland, Dr. Deborah Meem Abstract This dissertation focuses on the recent popularity of the tragicomedy as a genre for representing queer lives in late-twentieth and twenty-first century America. I argue that the tragicomedy allows for a nuanced portrayal of queer identity because it recognizes the systemic and personal “tragedies” faced by LGBTQ people (discrimination, inadequate legal protection, familial exile, the AIDS epidemic, et cetera), but also acknowledges that even in struggle, in real life and in art, there is humor and comedy. I contend that the contemporary tragicomedy works to depart from the dominant late-nineteenth and twentieth-century trope of queer people as either tragic figures (sick, suicidal, self-loathing) or comedic relief characters by showing complex characters that experience both tragedy and comedy and are themselves both serious and humorous. Building off Verna A. Foster’s 2004 book The Name and Nature of Tragicomedy, I argue that contemporary examples of the tragicomedy share generic characteristics with tragicomedies from previous eras (most notably the Renaissance and modern period), but have also evolved in important ways to work for queer authors. The contemporary tragicomedy, as used by queer authors, mixes comedy and tragedy throughout the text but ultimately ends in “comedy” (meaning the characters survive the tragedies in the text and are optimistic for the future). -

BBC Trust’S Review of BBC Services for Younger Audiences

Channel 4 submission to the BBC Trust’s review of BBC services for younger audiences 1. Channel 4 welcomes the opportunity to provide its views to the BBC Trust’s review of BBC services for younger audiences. Channel 4 is a publicly-owned, commercially-funded public service broadcaster. Its core public service channel, Channel 4, is a free-to-air service funded predominantly by advertising. Unlike the other commercially-funded public service broadcasters, Channel 4 is not shareholder owned: commercial revenue is only a means to delivering Channel 4’s public purpose end and any surplus revenues are reinvested in the delivery of its public service remit. 2. In recent years, Channel 4 has broadened its portfolio to offer a range of digital services, including the free-to-air, commercially-funded digital television channels Channel 4+1, E4, E4+1, Film4, More4 and 4Music. Channel 4 also offers a video on demand service, 4oD, and it is expanding its range of services at channel4.com. In addition, Channel 4 offers a range of online education projects for 14 to 19 year olds and has launched an innovation pilot fund, 4iP, which seeks to stimulate whole new digital media services across a range of areas, including video games, the arts, democracy and sport. 3. These innovations have allowed Channel 4 to stay in touch with audiences— especially younger viewers—who are rapidly migrating to digital media. Ever since its launch in 1982, Channel 4’s brand has resonated particularly strongly with teenagers and younger adults, and the organisation speaks with an authenticity of voice which is not easily replicated by other public institutions. -

Mullerpinzler2015

Europe PMC Funders Group Author Manuscript Neuroimage. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 September 01. Published in final edited form as: Neuroimage. 2015 October 1; 119: 252–261. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.06.036. Europe PMC Funders Author Manuscripts Neural Pathways of Embarrassment and their Modulation by Social Anxiety L Müller-Pinzlera,b, V Gazzolac,d, C Keysersd, J Sommere, A Jansene, S Frässleb,e, W Einhäuserf, FM Paulus#a, and S Krach#a,* aDepartment of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Social Neuroscience Lab | SNL, University of Lübeck, Ratzeburger Allee 160, D-23538 Lübeck, Germany bDepartment of Psychiatry, University of Marburg, Rudolf-Bultmann-Straße 8, D-35033 Marburg, Germany cDepartment of Neuroscience, University Medical Center Groningen, 9713 AW Groningen, The Netherlands dSocial Brain Laboratory, The Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience, Royal Netherlands Academy for the Arts and Sciences, 1105 BA Amsterdam, The Netherlands eDepartment of Child- and Adolescent Psychiatry, University of Marburg, Schützenstr. 49, D-35033 Marburg, Germany fInstitut für Physik, Physics of Cognitive Processes, TU Chemnitz, Reichenhainer Str. 70, 09107 Chemnitz, Germany # These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract While being in the center of attention and exposed to other’s evaluations humans are prone to Europe PMC Funders Author Manuscripts experience embarrassment. To characterize the neural underpinnings of such aversive moments, we induced genuine experiences of embarrassment during person-group interactions in a functional neuroimaging study. Using a mock-up scenario with three confederates, we examined how the presence of an audience affected physiological and neural responses and the reported emotional experiences of failures and achievements. The results indicated that publicity induced activations in mentalizing areas and failures led to activations in arousal processing systems. -

Fawlty Towers - Episode Guide

Performances October 6, 7, 8, 13, 14, 15 Three episodes of the classic TV series are brought to life on stage. Written by John Cleese & Connie Booth. Music by Dennis Wilson By Special Arrangement With Samuel French and Origin Theatrical Auditions Saturday June 18, Sunday June 19 Thurgoona Community Centre 10 Kosciuszko Road, Thurgoona NSW 2640 Director: Alex 0410 933 582 FAWLTY TOWERS - EPISODE GUIDE ACT ONE – THE GERMANS Sybil is in hospital for her ingrowing toenail. “Perhaps they'll have it mounted for me,” mutters Basil as he tries to cope during her absence. The fire-drill ends in chaos with Basil knocked out by the moose’s head in the lobby. The deranged host then encounters the Germans and tells them the “truth” about their Fatherland… ACT TWO – COMMUNICATION PROBLEMS It’s not a wise man who entrusts his furtive winnings on the horses to an absent-minded geriatric Major, but Basil was never known for that quality. Parting with those ill-gotten gains was Basil’s first mistake; his second was to tangle with the intermittently deaf Mrs Richards. ACT THREE – WALDORF SALAD Mine host's penny-pinching catches up with him as an American guest demands the quality of service not normally associated with the “Torquay Riviera”, as Basil calls his neck of the woods. A Waldorf Salad is not part of Fawlty Towers' standard culinary repertoire, nor is a Screwdriver to be found on the hotel's drinks list… FAWLTY TOWERS – THE REGULARS BASIL FAWLTY (John Cleese) The hotel manager from hell, Basil seems convinced that Fawlty Towers would be a top-rate establishment, if only he didn't have to bother with the guests. -

Review of the Film Sector in Scotland Creative Scotland

Review of the Film Sector in Scotland Creative Scotland January 2014 This report was produced by: BOP Consulting (www.bop.co.uk) in partnership with: Whetstone Group (www.whetstonegroup.org) Jonathan Olsberg (www.o-spi.com) If you would like to know more about the report, please contact the project’s director, Barbara McKissack: Email: [email protected] Tel: 0207 253 2041 i Contents 4.6 Festivals ........................................................................................... 17 1. Executive Summary ............................................... 1 4.7 Archives ........................................................................................... 18 1.1 Introduction ....................................................................................... 1 4.8 Cultural impact of film ................................................................... 18 1.2 Watching film ..................................................................................... 1 4.9 Consultants’ assessment of the issues ..................................... 19 1.3 Learning about film .......................................................................... 1 1.4 Making film ........................................................................................ 2 5. Learning about film ............................................. 21 1.5 Earning from film – supporting enterprises and 5.1 Introduction .....................................................................................21 employment ...................................................................................... -

Strategies for Promoting Affordable Housing in Oslo: a Case of Strong Path Dependence?

Hildegunn Elstad Christiansen Strategies for promoting affordable housing in Oslo: a case of strong path dependence? A master’s thesis in International Social Welfare and Health Policy Supervisor: Jardar Sørvoll Oslo, November 2020 Oslo Metropolitan University Faculty of Social Science Department of Social Work, Child Welfare and Social Policy Summary This paper is an analysis of the new policy paper for the provision of affordable housing in Oslo, ‘Nye veier til egen bolig’ (new paths to a permanent home), launched by the City Government of Oslo in January 2019. The policy paper is examined in the theoretical light provided by Bengtsson and Ruonavaara’s weak (non-deterministic) conception of path dependence. I have identified the main political strategies for the provision of affordable housing in Oslo and mapped out four criteria based on three key moments (critical junctures) of in Norwegian housing history that I have used to discuss and measure the degree of path dependence in the affordable housing strategies: owner-orientation, rental-friendliness, market-orientation and subsidy-friendliness. The Danish housing scheme Almenbolig+ is included as a comparative element in the analysis, as the City Government have suggested to adapt this from Copenhagen. In the discussion I argue that there are varying degrees of path dependence in today’s affordable housing strategies, but the main tendency is that ownership strategies are the most emphasized and that the ambivalence towards rental housing still persists. The research questions of this paper are: 1) What are the main political strategies of the new policy paper (Nye veier til egen bolig) for the provision of affordable housing in Oslo? 2) To what extent do the affordable housing strategies of the City Government and the surrounding political debates reflect a strong path dependency? The purpose of this study is to shed light on the historical preconditions shaping the affordable housing strategies in Oslo. -

Patrons' Newsletter Diary

Patrons’Volume 2, Issue 7 | April 2013Newsletter May Fawlty Towers Sandy Wilson’s Written by John Cleese & Connie The Boy Friend 10 Booth Maghull Musical Theatre Company Directed by Les Gomersall By arrangement with Samuel French May 10th - 18th June 12th - 15th Box Office Opens 3rd May Box Office Opens 5th June Carousel Advance Booking on 01695 632372 Diary Birkdale Orpheus Society Coming soon to the Little Theatre Music by Richard Rodgers, book & lyrics by Oscar An Evening of Music with Old Hammerstein II May 25th - June 1st Hall Brass Sunday 16th June 2013 Box office opens 18th May 2013 Advance Booking 01942715684 Acorn Antiques: The Musical Advanced Booking on 01704 564042 Southport Spotlights Musical Theatre Company Damages Music, lyrics and script by Victoria Woods June June 29th - July 6th, Matinee July 6th Written by Stephen Thompson Loreto Bamber Dance Show Directed by Stephen Huges-Alty Box office opens 24th June 2013 4 Friday 21st - 22nd June 2013 Advanced Booking on 07927 331977 An SDC Bar/Studio Production Box Office Opens 20th June June 4th - 8th Advance Booking 01704 538351 Box Office Opens 28th May ‘Fawlty Towers’ A comedy By Les Gomersall, Director In the early 1970s John Cleese was unusual hotelier Donald Sinclair. a member of the highly success- The result of course turned out to ful Monty Python’s Flying Circus be Fawlty Towers owned and run team. In May 1971 the team were by the equally unusual, but ex- staying at the Gleneagles Hotel in tremely funny, Basil Fawlty Torquay which was owned and run Only 12 episodes were written, by a Mr Donald Sinclair.