Review 18 No 1.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re-Appraising Taxation in Travancore and It's Caste Interference

GIS Business ISSN: 1430-3663 Vol-14-Issue-3-May-June-2019 Re-Appraising Taxation in Travancore and It's Caste Interference REVATHY V S Research Scholar Department Of History University Of Kerala [email protected] 8281589143 Travancore , one of the Princely States in British India and later became the Model State in British India carried a significant role in history when analysing its system of taxation. Tax is one of the chief means for acquiring revenue and wealth. In the modern sense, tax means an amount of money imposed by a government on its citizens to run a state or government. But the system of taxation in the Native States of Travancore had an unequal character or discriminatory character and which was bound up with the caste system. In the case of Travancore and its society, the so called caste system brings artificial boundaries in the society.1 The taxation in Travancore is mainly derived through direct tax, indirect tax, commercial tax and taxes in connection with the specific services. The system of taxation adopted by the Travancore Royal Family was oppressive and which was adversely affected to the lower castes, women and common people. It is proven that the system of taxation used by the Royal Family as a tool for oppression and subjugation and they also used this P a g e | 207 Copyright ⓒ 2019 Authors GIS Business ISSN: 1430-3663 Vol-14-Issue-3-May-June-2019 discriminatorytaxation policies as of the ardent machinery to establish their political domination and establishing their cultural hegemony. Through the analysis and study of taxation in Travancore it is helpful to reconstruct the socio-economic , political and cultural conditions of Travancore. -

Dress As a Tool of Empowerment : the Channar Revolt

Dress as a tool of Empowerment : The Channar Revolt Keerthana Santhosh Assistant Professor (Part time Research Scholar – Reg. No. 19122211082008) Department of History St. Mary’s College, Thoothukudi (Manonmanium Sundaranar sUniversity, Tirunelveli) Abstract Empowerment simply means strengthening of women. Travancore, an erstwhile princely state of modern Kerala was considered as a land of enlightened rulers. In the realm of women, condition of Travancore was not an exception. Women were considered as a weaker section and were brutally tortured.Patriarchy was the rule of the land. Many agitations occurred in Travancore for the upliftment of women. The most important among them was the Channar revolt, which revolves around women’s right to wear dress. The present paper analyses the significance of Channar Revolt in the then Kerala society. Keywords: Channar, Mulakkaram, Kuppayam 53 | P a g e Dress as a tool of Empowerment : The Channar Revolt Kerala is considered as the God’s own country. In the realm of human development, it leads India. Regarding women empowerment also, Kerala is a model. In women education, health indices etc. there are no parallels. But everything was not better in pre-modern Kerala. Women suffered a lot of issues. Even the right to dress properly was neglected to the women folk of Kerala. So what Kerala women had achieved today is a result of their continuous struggles. Women in Travancore, which was an erstwhile princely state of Kerala, irrespective of their caste and community suffered a lot of problems. The most pathetic thing was the issue of dress. Women of lower castes were not given the right to wear dress above their waist. -

Download Download

Volume 02 :: Issue 01 April 2021 A Global Journal ISSN 2639-4928 CASTE on Social Exclusion brandeis.edu/j-caste PERSPECTIVES ON EMANCIPATION EDITORIAL AND INTRODUCTION “I Can’t Breathe”: Perspectives on Emancipation from Caste Laurence Simon ARTICLES A Commentary on Ambedkar’s Posthumously Published Philosophy of Hinduism - Part II Rajesh Sampath Caste, The Origins of Our Discontents: A Historical Reflection on Two Cultures Ibrahim K. Sundiata Fracturing the Historical Continuity on Truth: Jotiba Phule in the Quest for Personhood of Shudras Snehashish Das Documenting a Caste: The Chakkiliyars in Colonial and Missionary Documents in India S. Gunasekaran Manual Scavenging in India: The Banality of an Everyday Crime Shiva Shankar and Kanthi Swaroop Hate Speech against Dalits on Social Media: Would a Penny Sparrow be Prosecuted in India for Online Hate Speech? Devanshu Sajlan Indian Media and Caste: of Politics, Portrayals and Beyond Pranjali Kureel ‘Ambedkar’s Constitution’: A Radical Phenomenon in Anti-Caste Discourse? Anurag Bhaskar, Bluestone Rising Scholar 2021 Award Caste-ing Space: Mapping the Dynamics of Untouchability in Rural Bihar, India Indulata Prasad, Bluestone Rising Scholar 2021 Award Caste, Reading-habits and the Incomplete Project of Indian Democracy Subro Saha, Bluestone Rising Scholar Honorable Mention 2021 Clearing of the Ground – Ambedkar’s Method of Reading Ankit Kawade, Bluestone Rising Scholar Honorable Mention 2021 Caste and Counselling Psychology in India: Dalit Perspectives in Theory and Practice Meena Sawariya, Bluestone Rising Scholar Honorable Mention 2021 FORUM Journey with Rural Identity and Linguicism Deepak Kumar Drawing on paper; 35x36 cm; Savi Sawarkar 35x36 cm; Savi on paper; Drawing CENTER FOR GLOBAL DEVELOPMENT + SUSTAINABILITY THE HELLER SCHOOL AT BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY CASTE A GLOBAL JOURNAL ON SOCIAL EXCLUSION PERSPECTIVES ON EMANCIPATION VOLUME 2, ISSUE 1 JOINT EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Laurence R. -

Agatti Island, UT of Lakshadweep

Socioeconomic Monitoring for Coastal Managers of South Asia: Field Trials and Baseline Surveys Agatti Island, UT of Lakshadweep Project completion Report: NA10NOS4630055 Project Supervisor : Vineeta Hoon Site Coordinators: Idrees Babu and Noushad Mohammed Agatti team: Amina.K, Abida.FM, Bushra M.I, Busthanudheen P.K, Hajarabeebi MC, Hassan K, Kadeeshoma C.P, Koyamon K.G, Namsir Babu.MS, Noorul Ameen T.K, Mohammed Abdul Raheem D A, Shahnas beegam.k, Shahnas.K.P, Sikandar Hussain, Zakeer Husain, C.K, March 2012 This volume contains the results of the Socioeconomic Assessment and monitoring project supported by IUCN/ NOAA Prepared by: 1. The Centre for Action Research on Environment Science and Society, Chennai 600 094 2. Lakshadweep Marine Research and Conservation Centre, Kavaratti island, U.T of Lakshadweep. Citation: Vineeta Hoon and Idrees Babu, 2012, Socioeconomic Monitoring and Assessment for Coral Reef Management at Agatti Island, UT of Lakshadweep, CARESS/ LMRCC, India Cover Photo: A reef fisherman selling his catch Photo credit: Idrees Babu 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 7 Acknowledgements 8 Glossary of Native Terms 9 List of Acronyms 10 1. Introduction 11 1.1 Settlement History 11 1.2 Dependence on Marine Resources 13 1.3 Project Goals 15 1.4 Report Chapters 15 2. Methodology of Project Execution 17 2.1 SocMon Workshop 17 2.2 Data Collection 18 2.3 Data Validation 20 3. Site Description and Island Infrastructure 21 3.1 Site description 23 3.2. Community Infrastructure 25 4. Community Level Demographics 29 4.1 Socio cultural status 29 4.2 Land Ownership 29 4.3 Demographic characteristics 30 4.4 Household size 30 4.5. -

Women and Political Change in Kerala Since Independence

WOMEN AND POLITICAL CHANGE IN KERALA SINCE INDEPENDENCE THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE COCHIN UNIVERSITY or SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY FOR THE AWARD or THE DEGREE or DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNDER THE FACULTY or SOCIAL SCIENCES BY KOCHUTHRESSIA, M. M. UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. J. T. PAYYAPPILLY PROFESSOR SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT STUDIES COCHIN UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY COCHIN - 682 022, KERALA October 1 994 CERTIFICATE Certified that the thesis "Women and Political Change in Kerala since Independence" is the record of bona fide research carried out by Kochuthressia, M.M. under my supervision. The thesis is worth submitting for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Faculty of Social Sciences. 2’/1, 1 :3£7:L§¢»Q i9¢Z{:;,L<‘ Professorfir.J.T.§ay§a%pilly///// ” School of Management Studies Cochin University of Science and Technology Cochin 682 022 Cochin 682 022 12-10-1994 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is the record of bona fide research work carried out knrxme under the supervision of Dr.J.T.Payyappilly, School (HS Management. Studies, Cochin University of Science and Technology, Cochin 682 022. I further declare that this thesis has not previously formed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma, associateship, fellowship or other similar title of recognition. ¥E;neL£C-fl:H12§LJJ;/f1;H. Kochuthfe§§ia7—§iM. Cochin 682 022 12-10-1994 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Once the topic "Women and Political Change in Kerala since Independence" was selected for the study, I received a lot of encouragement from many men and women who'are genuinely concerned about the results (M5 gender discrimination. -

"An Evaluation of the History of Pentecostal Dalits in Kerala"

INTRODUCTION Research and studies have recently been initiated on the under-privileged people, namely, the Dalits in India. Though it is an encouraging fact, yet more systematic and classified studies are required because the Dalits are located over a wide range of areas, languages, cultures, and religions, where as the problems and solutions vary. Since the scholars and historians have ignored the Dalits for many centuries, a general study will not expose sufficiently their actual condition. Even though the Dalit Christian problems are resembling, Catholics and Protestants are divided over the issues. Some of the Roman Catholic priests are interested and assert their solidarity with the Dalit Christian struggle for equal privilege from the Government like other Hindu Dalits. On the other hand, most Protestant denominations are indifferent towards any public or democratic means of agitation on behalf of Dalit community. They are very crafty and admonish Dalit believers only to pray and wait for God’s intervention. However, there is an apparent intolerance in the Church towards the study and observations concerning the problems of Dalit Christians because many unfair treatments have been critically exposed. T.N. Gopakumar, the Asia Net programmer, did broadcast a slot on Dr. P.J. Joseph, a Catholic priest for thirty -eight years in the Esaw Church, on 22 October 2000. 1 Joseph advocated for the converted Christians that the Church should upgrade their place and participation in the leadership of the Church. The very next day, 1 T.N.Gopakumar, Kannady [Mirror-Mal], Asia Net , broadcast on 22 October, 2000. 1 with the knowledge of the authorities, a group of anti-Dalit Church members, attacked him and threw out this belongings from his room in the headquarters at Malapparambu, Kozhikode, where he lived for about thirty years. -

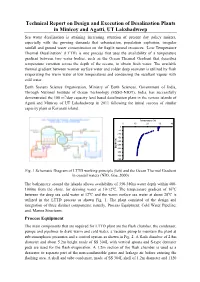

Technical Report on Design and Execution of Desalination Plants in Minicoy and Agatti, UT Lakshadweep

Technical Report on Design and Execution of Desalination Plants in Minicoy and Agatti, UT Lakshadweep Sea water desalination is attaining increasing attention of present day policy makers, especially with the growing demands that urbanization, population explosion, irregular rainfall and ground water contamination on the fragile natural resources. ‘Low Temperature Thermal Desalination’ (LTTD) is one process that uses the availability of a temperature gradient between two water bodies, such as the Ocean Thermal Gradient that describes temperature variation across the depth of the oceans, to obtain fresh water. The available thermal gradient between warmer surface water and colder deep seawater is utilized by flash evaporating the warm water at low temperatures and condensing the resultant vapour with cold water. Earth System Science Organization, Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India, Through National Institute of Ocean Technology (ESSO-NIOT), India, has successfully demonstrated the 100 m3/day capacity land based desalination plant in the remote islands of Agatti and Minicoy of UT Lakshadweep in 2011 following the initial success of similar capacity plant at Kavaratti island. Temperature (oC) 0 10 20 30 40 0 -50 -100 -150 -200 -250 Depth (m) Depth -300 -350 -400 -450 Fig. 1 Schematic Diagram of LTTD working principle (left) and the Ocean Thermal Gradient in coastal waters (NIO, Goa, 2000) The bathymetry around the islands allows availability of 350-380m water depth within 400- 1000m from the shore, for drawing water at 10-12oC. The temperature gradient of 16oC between the deep sea cold water at 12oC and the warm surface sea water at about 28oC is utilized in the LTTD process as shown Fig. -

Expression of Interest for Development of Lighthouse Tourism on PPP Mode

EOI for 65 Lighthouse Sites for development of Lighthouse Tourism Projects on PPP Mode Government of India Ministry of Ports, Shipping & Waterways Directorate General of Lighthouses & Lightships INTEREST Expression of Interest for 65 OF Lighthouse Sites for Development of Lighthouse Tourism Projects on Public Private Partnership Mode April, 2021 EXPRESSION Directorate General of Lighthouses & Lightships, Ministry of Ports, Shipping & Waterways, Government of India 1 EOI for 65 Lighthouse Sites for development of Lighthouse Tourism Projects on PPP Mode Table of contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Tourism of India 3 3. Promotion of tourism at Lighthouses across India 3 3.1 The Expression of Interest (EOI) 4 3.2 Contact Details 5-6 4 Schedule I: Details of Lighthouse site 7-10 5 Schedule II: Indicative terms and conditions 11 6. Schedule III: Formats for Expression of Interest 12 6.1 Letter of Application 12-13 6.2 Details of Applicant 14-15 6.3 Details of development interest for specific Lighthouse location 16-17 7 Schedule IV: Mapping of Lighthouses 18-84 2 EOI for Development of Tourism Projects at selected Lighthouses across India on PPP Mode F.No. T-201/1/2020-TC Date: 09/04/2021 1 Introduction Globally, Lighthouses are not only perceived as a navigational aid, but also as a symbol of history & icons of maritime heritage and are being developed into unique tourism destinations. While the presence of historic lighthouses act as a driver to attract tourists across the globe, the spectacular panoramic vistas available from these tall structures along the coastline add on to the attractiveness of the locations. -

2020030324.Pdf

郸觀 郸GOVT. OF INDIA NDIA 郸 LAKSHADWEEP ADMINISTRATION ͬI郸 I郸 郸(Secretariat – Service Section) I⟦A DIA /^^^Kavaratti Island – 682 555 Change Request Form Recruitment 2019 - 2020 Name:___________________________________________________________ DOB:_______________Contact No.______________________________ Address:_________________________________________________________ Post (as Roll No. (as Changes to be made applicable) applicable) U- UD Clerk Stenogr S- apher L- LD Clerk Multi Skilled M- Employee (MSE) Signature of the applicant Email: [email protected] Details of applicants who have applied for the post of UDC vide F.No.12/45/2019-Services\3160 dated 21.10.2019 and F.No.12/33/2019-Services/384 dated 10.02.2020 Sl. No. Roll No. Name Father/Mother Name Date of Age Comm Permanent Address Address For Native Exam Remar Birth unity Communication Center ks 1 U-153 Abdul Ameer Babu.U Hamza.C 13/01/1986 33 ST Uppathoda, Agatti Uppathoda, Agatti Agatti Kochi 2 U-1603 Abdul Bari.PP Kidave.TK (Late) 08/12/1984 34 ST Pulippura House, Agathi. Pulippura House, Agatti Agatti Agathi. 3 U-1013 Abdul Gafoor.P.K Koyassan.K.C 16/03/1987 32 ST Punnakkod House, Agathi. Punnakkod House, Agatti Agatti Agathi. 4 U-810 Abdul Gafoor.TP Ummer koya.p 28/11/1986 32 ST Thekku Puthiya LDC General Section Agatti Kavarat [Govt. illam,Agatti Kavaratti ti Ser] 5 U-1209 Abdul hakeem.K Kasmikoya.P 02/08/1991 28 ST Keepattu Agatti Keepattu Agatti Agatti Agatti 6 U-821 Abdul Hakeem.M.M Abdul Naser.P 04/08/1992 27 ST Mubarak Manzil (H), Agatti Mubarak Manzil (H), Agatti Kavarat [Govt. -

Atoll Research Bulletin No. 506 Distribution And

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 506 DISTRIBUTION AND DIVERSITY OF MARINE FLORA IN CORAL REEF ECOSYSTEMS OF KADMAT ISLAND IN LAKSHADWEEP ARCHIPELAGO, ARABIAN SEA, INDIA VIJAY V. DESAI, DEEPALI S. KOMARPANT AND TANAJI G. JAGTAP ISSUED BY NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WASHINGTON, D.C., U.S.A. AUGUST 2003 1 SCALE Figurel. Physical data and morphological features of coral reef fiom Kadmat Island (the numbers in parenthesis refer to an area in km2). DISTRIBUTION AND DIVERSITY OF MARINE FLORA IN CORAL REEF ECOSYSTEMS OF KADMAT ISLAND IN LAKSHADWEEP ARCHIPELAGO, ARABIAN SEA, INDIA. VIJAY V. DESAI ', DEEPALI S. KOMARPANT and TANAJI G. JAGTAP ABSTRACT The coral reef of Kadmat Island of Lakshadweep was assessed for its biological components along with relevant hydrological characteristics. Corals were represented by 12 species, the most dominant being Acropora and Porites. The distribution of coral was mainly confined to the reef slope and fore reef; however, the cover was very poor except for a few patches on the fore reef towards northwest (< 10%). The lagoon and reef flats were almost devoid of corals. The low counts (0-80x10~ cells I-') and poor composition (11 spp.) of phytoplanktons could be due to oligotrophic waters around the island. The high contents of dissolved oxygen (DO) might be due to photosynthetic activities of macrophytes in the lagoon. Seagrass meadow occupied only 0.14 km2 area of the lagoon leaving 98% of it barren. It was more prominent in the mid- and landward region of the lagoon due to fine and well-sorted thick sediment. Seagrass flora was comprised of two species and was dominated by Cymodocea rotundata. -

Prioritized Species for Mariculture in India

Prioritized Species for Mariculture in India Compiled & Edited by Ritesh Ranjan Muktha M Shubhadeep Ghosh A Gopalakrishnan G Gopakumar Imelda Joseph ICAR - Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute Post Box No. 1603, Ernakulam North P.O. Kochi – 682 018, Kerala, India www.cmfri.org.in 2017 Prioritized Species for Mariculture in India Published by: Dr. A Gopalakrishnan Director ICAR - Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute Post Box No. 1603, Ernakulam North P.O. Kochi – 682 018, Kerala, India www.cmfri.org.in Email: [email protected] Tel. No.: +91-0484-2394867 Fax No.: +91-0484-2394909 Designed at G.K. Print House Pvt. Ltd. Rednam Gardens Visakhapatnam- 530002, Andhra Pradesh Cell: +91 9848196095, www.gkprinthouse.com Cover page design: Abhilash P. R., CMFRI, Kochi Illustrations: David K. M., CMFRI, Kochi Publication, Production & Co-ordination: Library & Documentation Centre, CMFRI Printed on: November 2017 ISBN 978-93-82263-14-2 © 2017 ICAR - Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Kochi All rights reserved. Material contained in this publication may not be reproduced in any form without the permission of the publisher. Citation : Ranjan, R., Muktha, M., Ghosh, S., Gopalakrishnan, A., Gopakumar, G. and Joseph, I. (Eds.). 2017. Prioritized Species for Mariculture in India. ICAR-CMFRI, Kochi. 450 pp. CONTENTS Foreword ................................................................................................................. i Preface ................................................................................................................. -

CMFRI Bulletin 43

CMFRI bulletin 43 APRIL 1989 MARINE LIVING RESOURCES OF THE UNION TERRITORY OF LAKSHADWEEP- An Indicative Survey With Suggestions For Development CENTRAL MARINE FISHERIES RESEARCH INSTITUTE (Indian Council of Agricultural Research) P, B. No. 2704, E. R. G. Road, Cochin-682 031, India Bulletins are issued periodically by Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute to interpret current knowledge in the various fields of research on marine fisheries and allied subjects in India Copyright Reserved © Published by P. S. B. R. JAMES Director Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute Cochin 682031, India Edited by C. SUSEELAN Scientist Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute Cochin 682031, India Limited Circulation 2. HISTORY OF MARINE RESEARCH IN LAKSHADWEEP p. S. B. R. James INTRODUCTION some environmental parameters. With the reali sation of the importance and scope for further The Lakshadweep consisting of a number development, attention is now being paid to of islands, islets and submerged reefs lie scattered take stock of the marine living resources by in the vast Arabian sea on the west coast of India. proper survey to assess and monitor these This geographic isolation has been a major resources to postulate management measures. impediment to maintain status quo with the progress and developmental activities on the The present review is to document all mainland. Of recent, the stress has been to available information on marine research in achieve a conduce growth of the economy of the Lakshadweep. The paper highlights essential islanders so as to improve their standard of aspects concerning the marine biological, living. Besides agriculture the traditional source fisheries and oceanographic research carried out of livelihood of the islanders is fishing which in Lakshadweep.