Calculus Review Handout

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes on Calculus II Integral Calculus Miguel A. Lerma

Notes on Calculus II Integral Calculus Miguel A. Lerma November 22, 2002 Contents Introduction 5 Chapter 1. Integrals 6 1.1. Areas and Distances. The Definite Integral 6 1.2. The Evaluation Theorem 11 1.3. The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus 14 1.4. The Substitution Rule 16 1.5. Integration by Parts 21 1.6. Trigonometric Integrals and Trigonometric Substitutions 26 1.7. Partial Fractions 32 1.8. Integration using Tables and CAS 39 1.9. Numerical Integration 41 1.10. Improper Integrals 46 Chapter 2. Applications of Integration 50 2.1. More about Areas 50 2.2. Volumes 52 2.3. Arc Length, Parametric Curves 57 2.4. Average Value of a Function (Mean Value Theorem) 61 2.5. Applications to Physics and Engineering 63 2.6. Probability 69 Chapter 3. Differential Equations 74 3.1. Differential Equations and Separable Equations 74 3.2. Directional Fields and Euler’s Method 78 3.3. Exponential Growth and Decay 80 Chapter 4. Infinite Sequences and Series 83 4.1. Sequences 83 4.2. Series 88 4.3. The Integral and Comparison Tests 92 4.4. Other Convergence Tests 96 4.5. Power Series 98 4.6. Representation of Functions as Power Series 100 4.7. Taylor and MacLaurin Series 103 3 CONTENTS 4 4.8. Applications of Taylor Polynomials 109 Appendix A. Hyperbolic Functions 113 A.1. Hyperbolic Functions 113 Appendix B. Various Formulas 118 B.1. Summation Formulas 118 Appendix C. Table of Integrals 119 Introduction These notes are intended to be a summary of the main ideas in course MATH 214-2: Integral Calculus. -

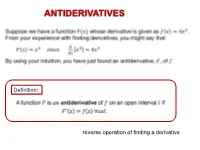

Notes Chapter 4(Integration) Definition of an Antiderivative

1 Notes Chapter 4(Integration) Definition of an Antiderivative: A function F is an antiderivative of f on an interval I if for all x in I. Representation of Antiderivatives: If F is an antiderivative of f on an interval I, then G is an antiderivative of f on the interval I if and only if G is of the form G(x) = F(x) + C, for all x in I where C is a constant. Sigma Notation: The sum of n terms a1,a2,a3,…,an is written as where I is the index of summation, ai is the ith term of the sum, and the upper and lower bounds of summation are n and 1. Summation Formulas: 1. 2. 3. 4. Limits of the Lower and Upper Sums: Let f be continuous and nonnegative on the interval [a,b]. The limits as n of both the lower and upper sums exist and are equal to each other. That is, where are the minimum and maximum values of f on the subinterval. Definition of the Area of a Region in the Plane: Let f be continuous and nonnegative on the interval [a,b]. The area if a region bounded by the graph of f, the x-axis and the vertical lines x=a and x=b is Area = where . Definition of a Riemann Sum: Let f be defined on the closed interval [a,b], and let be a partition of [a,b] given by a =x0<x1<x2<…<xn-1<xn=b where xi is the width of the ith subinterval. -

Calculus Formulas and Theorems

Formulas and Theorems for Reference I. Tbigonometric Formulas l. sin2d+c,cis2d:1 sec2d l*cot20:<:sc:20 +.I sin(-d) : -sitt0 t,rs(-//) = t r1sl/ : -tallH 7. sin(A* B) :sitrAcosB*silBcosA 8. : siri A cos B - siu B <:os,;l 9. cos(A+ B) - cos,4cos B - siuA siriB 10. cos(A- B) : cosA cosB + silrA sirrB 11. 2 sirrd t:osd 12. <'os20- coS2(i - siu20 : 2<'os2o - I - 1 - 2sin20 I 13. tan d : <.rft0 (:ost/ I 14. <:ol0 : sirrd tattH 1 15. (:OS I/ 1 16. cscd - ri" 6i /F tl r(. cos[I ^ -el : sitt d \l 18. -01 : COSA 215 216 Formulas and Theorems II. Differentiation Formulas !(r") - trr:"-1 Q,:I' ]tra-fg'+gf' gJ'-,f g' - * (i) ,l' ,I - (tt(.r))9'(.,') ,i;.[tyt.rt) l'' d, \ (sttt rrJ .* ('oqI' .7, tJ, \ . ./ stll lr dr. l('os J { 1a,,,t,:r) - .,' o.t "11'2 1(<,ot.r') - (,.(,2.r' Q:T rl , (sc'c:.r'J: sPl'.r tall 11 ,7, d, - (<:s<t.r,; - (ls(].]'(rot;.r fr("'),t -.'' ,1 - fr(u") o,'ltrc ,l ,, 1 ' tlll ri - (l.t' .f d,^ --: I -iAl'CSllLl'l t!.r' J1 - rz 1(Arcsi' r) : oT Il12 Formulas and Theorems 2I7 III. Integration Formulas 1. ,f "or:artC 2. [\0,-trrlrl *(' .t "r 3. [,' ,t.,: r^x| (' ,I 4. In' a,,: lL , ,' .l 111Q 5. In., a.r: .rhr.r' .r r (' ,l f 6. sirr.r d.r' - ( os.r'-t C ./ 7. /.,,.r' dr : sitr.i'| (' .t 8. tl:r:hr sec,rl+ C or ln Jccrsrl+ C ,f'r^rr f 9. -

13.1 Antiderivatives and Indefinite Integrals

ANTIDERIVATIVES Definition: reverse operation of finding a derivative Notice that F is called AN antiderivative and not THE antiderivative. This is easily understood by looking at the example above. Some antiderivatives of 푓 푥 = 4푥3 are 퐹 푥 = 푥4, 퐹 푥 = 푥4 + 2, 퐹 푥 = 푥4 − 52 Because in each case 푑 퐹(푥) = 4푥3 푑푥 Theorem 1: If a function has more than one antiderivative, then the antiderivatives differ by a constant. • The graphs of antiderivatives are vertical translations of each other. • For example: 푓(푥) = 2푥 Find several functions that are the antiderivatives for 푓(푥) Answer: 푥2, 푥2 + 1, 푥2 + 3, 푥2 − 2, 푥2 + 푐 (푐 푖푠 푎푛푦 푟푒푎푙 푛푢푚푏푒푟) INDEFINITE INTEGRALS Let f (x) be a function. The family of all functions that are antiderivatives of f (x) is called the indefinite integral and has the symbol f (x) dx The symbol is called an integral sign, The function 푓 (푥) is called the integrand. The symbol 푑푥 indicates that anti-differentiation is performed with respect to the variable 푥. By the previous theorem, if 퐹(푥) is any antiderivative of 푓, then f (x) dx F(x) C The arbitrary constant C is called the constant of integration. Indefinite Integral Formulas and Properties Vocabulary: The indefinite integral of a function 푓(푥) is the family of all functions that are antiderivatives of 푓 (푥). It is a function 퐹(푥) whose derivative is 푓(푥). The definite integral of 푓(푥) between two limits 푎 and 푏 is the area under the curve from 푥 = 푎 to 푥 = 푏. -

Antiderivatives Math 121 Calculus II D Joyce, Spring 2013

Antiderivatives Math 121 Calculus II D Joyce, Spring 2013 Antiderivatives and the constant of integration. We'll start out this semester talking about antiderivatives. If the derivative of a function F isf, that is, F 0 = f, then we say F is an antiderivative of f. Of course, antiderivatives are important in solving problems when you know a derivative but not the function, but we'll soon see that lots of questions involving areas, volumes, and other things also come down to finding antiderivatives. That connection we'll see soon when we study the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus (FTC). For now, we'll just stick to the basic concept of antiderivatives. We can find antiderivatives of polynomials pretty easily. Suppose that we want to find an antiderivative F (x) of the polynomial f(x) = 4x3 + 5x2 − 3x + 8: We can find one by finding an antiderivative of each term and adding the results together. Since the derivative of x4 is 4x3, therefore an antiderivative of 4x3 is x4. It's not much harder to find an antiderivative of 5x2. Since the derivative of x3 is 3x2, an antiderivative of 5x2 is 5 3 3 x . Continue on and soon you see that an antiderivative of f(x) is 4 5 3 3 2 F (x) = x + 3 x − 2 x + 8x: There are, however, other antiderivatives of f(x). Since the derivative of a constant is 0, 4 5 3 3 2 we can add any constant to F (x) to find another antiderivative. Thus, x + 3 x − 2 x +8x+7 4 5 3 3 2 is another antiderivative of f(x). -

Appendix: TABLE of INTEGRALS

-~.I-- Appendix: TABLE OF INTEGRALS 148. In the following table, the constant of integration, C, is omitted but should be added to the result of every integration. The letter x represents any variable; u represents any function of x; the remaining letters represent arbitrary constants, unless otherwise indicated; all angles are in radians. Unless otherwise mentioned, loge u = log u. Expressions Containing ax + b 1. I(ax+ b)ndx= 1 (ax+ b)n+l, n=l=-1. a(n + 1) dx 1 2. = -loge<ax + b). Iax+ b a 3 I dx =_ 1 • (ax+b)2 a(ax+b)· 4 I dx =_ 1 • (ax + b)3 2a(ax + b)2· 5. Ix(ax + b)n dx = 1 (ax + b)n+2 a2 (n + 2) b ---,,---(ax + b)n+l n =1= -1, -2. a2 (n + 1) , xdx x b 6. = - - -2 log(ax + b). I ax+ b a a 7 I xdx = b 1 I ( b) • (ax + b)2 a2(ax + b) + -;}i og ax + . 369 370 • Appendix: Table of Integrals 8 I xdx = b _ 1 • (ax + b)3 2a2(ax + b)2 a2(ax + b) . 1 (ax+ b)n+3 (ax+ b)n+2 9. x2(ax + b)n dx = - - 2b--'------'-- I a2 n + 3 n + 2 2 b (ax + b) n+ 1 ) + , ni=-I,-2,-3. n+l 2 10. I x dx = ~ (.!..(ax + b)2 - 2b(ax + b) + b2 10g(ax + b)). ax+ b a 2 2 2 11. I x dx 2 =~(ax+ b) - 2blog(ax+ b) _ b ). (ax + b) a ax + b 2 2 12 I x dx = _1(10 (ax + b) + 2b _ b ) • (ax + b) 3 a3 g ax + b 2(ax + b) 2 . -

Integral Calculus

Integral Calculus 10 This unit is designed to introduce the learners to the basic concepts associated with Integral Calculus. Integral calculus can be classified and discussed into two threads. One is Indefinite Integral and the other one is Definite Integral . The learners will learn about indefinite integral, methods of integration, definite integral and application of integral calculus in business and economics. School of Business Blank Page Unit-10 Page-228 Bangladesh Open University Lesson-1: Indefinite Integral After completing this lesson, you should be able to: Describe the concept of integration; Determine the indefinite integral of a given function. Introduction The process of differentiation is used for finding derivatives and differentials of functions. On the other hand, the process of integration is used (i) for finding the limit of the sum of an infinite number of Reversing the process infinitesimals that are in the differential form f ′()x dx (ii) for finding of differentiation and finding the original functions whose derivatives or differentials are given, i.e., for finding function from the anti-derivatives. Thus, reversing the process of differentiation and derivative is called finding the original function from the derivative is called integration or integration. anti-differentiation. The integral calculus is used to find the areas, probabilities and to solve equations involving derivatives. Integration is also used to determine a function whose rate of change is known. In integration whether the object be summation or anti-differentiation, the sign ∫, an elongated S, the first letter of the word ‘sum’ is most generally used to indicate the process of the summation or integration. -

Indefinite Integrals

Arkansas Tech University MATH 2914: Calculus I Dr. Marcel B. Finan 5.3 Evaluating Definite Integrals: Indefinite Integrals In the previous section, we used Riemann sums to evaluate definite integrals. As you can tell, Riemann sums become hard to work with when the integrand function is complex. Therefore, a more convenient way for finding definite integrals is needed. This is provided by the following result. Theorem 5.3.1 (First Fundamental Theorem of Calculus) If f is continuous in [a; b] and F 0 = f then Z b f(x)dx = F (b) − F (a): a Recall that if s(t) is the position function of a moving object at time t then its velocity is given by v(t) = s0(t): Thus, we can apply the above theorem to find the displacement between the times a and b which is given by Z b v(t)dt = s(b) − s(a): a Recall that displacement can be positive (object moving to the right or upward) or negative (object moving to the left or downward). To find the total distance traveled, we compute Z b jv(t)jdt: a Remark 5.3.1 R b When using a f(x)dx in applications then its units is the product of the units of f(x) with the units of x: Example 5.3.1 R 2 Compute 1 2xdx: Solution. Since the derivative of x2 is 2x; F (x) = x2: Thus, we have Z 2 2xdx = F (2) − F (1) = 4 − 1 = 3 1 Indefinite Integrals Recall from Section 4.7 that a function f might have many antiderivatives. -

Chapter 11 Techniques of Integration

Chapter 11 Techniques of Integration Chapter 6 introduced the integral. There it was defined numerically, as the limit of approximating Riemann sums. Evaluating integrals by applying this basic definition tends to take a long time if a high level of accuracy is desired. If one is going to evaluate integrals at all frequently, it is thus important to find techniques of integration for doing this efficiently. For instance, if we evaluate a function at the midpoints of the subintervals, we get much faster convergence than if we use either the right or left endpoints of the subintervals. A powerful class of techniques is based on the observation made at the end of chapter 6, where we saw that the fundamental theorem of calculus gives us a second way to find an integral, using antiderivatives. While a Riemann sum will usually give us only an approximation to the value of an integral, an antiderivative will give us the exact value. The drawback is that antiderivatives often can’t be expressed in closed form—that is, as a formula in terms of named functions. Even when antiderivatives can be so expressed, the formulas are often difficult to find. Nevertheless, such a formula can be so powerful, both computationally and analytically, that it is often worth the effort needed to find it. In this chapter we will explore several techniques for finding the antiderivative of a function given by a formula. We will conclude the chapter by developing a numerical method—Simpson’s rule—that gives a good estimate for the value of an integral with relatively little computation. -

Barry Mcquarrie's Calculus I Glossary Asymptote: a Vertical Or Horizontal

Barry McQuarrie’s Calculus I Glossary Asymptote: A vertical or horizontal line on a graph which a function approaches. Antiderivative: The antiderivative of a function f(x) is another function F (x). If we take the derivative of F (x) the result is f(x). The most general antiderivative is a family of curves. Antidifferentiation: The process of finding an antiderivative of a function f(x). Concavity: Concavity measures how a function bends, or in other words, the function’s curvature. Concave Down: A function f(x) is concave down at x = a if it is below its tangent line at x = a. This is true if f 00(a) < 0. Concave Up: A function f(x) is concave up at x = a if it is above its tangent line at x = a. This is true if f 00(a) > 0. Constant of Integration: The constant that is included when an indefinite integral is performed. Z b Definite Integral: Formally, a definite integral looks like f(x)dx. A definite integral when evaluated yields a number. a The definite integral can be interpreted as the net area under the function f(x) from x = a to x = b. d Derivative: Formally, a derivative looks like f(x), and represents the rate of change of f(x) with respect to the dx variable x. Anther notation for derivative is f 0(x). Differential: Informally, a differential dx can be thought of a small amount of x. Differentials appear in both derivatives and integrals. Differentiation: The process of finding the derivative of a function f(x). -

Antiderivatives and Indefinite Integration

ANTIDERIVATIVES AND INDEFINITE INTEGRATION The opposite of a derivative is called an antiderivative or integral. Definition: A function F is an antiderivative of f on an interval I if for all x in I. EX #1: Antiderivatives differ only by a constant, C: C is called the constant of integration Family of all antiderivatives of f(x) = 2x and the general solution of the differential equation A differential equation in x and y is an equation that involves x, y, and derivatives of y. For example: and 1 EX #2: Solving a Differential Equation EX #3: Notation for antiderivatives: The operation of finding all solutions of this equation is called antidifferentiation or indefinite integration denoted by sign. differential form General Solution is denoted by: Variable of Constant of Integration Integration Integrand read as the antiderivative of f with respect to x. So, the differential dx serves to identify x as the variable of integration. The term indefinite integral is a synonym for antiderivative. 2 BASIC INTEGRATION RULES Integration is the “inverse” of differentiation. Differentiation is the “inverse” of integration. Differentiation Formula Integration Formula POWER RULE: 3 EX #4: Applying Basic Rules EX #5: Rewriting Before Integrating Original Integral Rewrite Integrate Simplify 4 EX # 6: Polynomial Functions A. B. C. EX #7: Integrate By Rewriting 5 EX #8: Solve differential equations subject to given conditions. Given: and 6 EX #9: A ball is thrown upward with an initial velocity of 64 feet per second from an initial height of 80 feet. A. Find the position function giving the height, s, as a function of the time t. -

1 Indefinite Integrals

November 16, 2019 MAT186 { Week 7 Justin Ko 1 Indefinite Integrals Definition 1. The antiderivative of f(x) on [a; b] is a function F (x) such that F 0(x) = f(x) for all x 2 [a; b]. The antiderivative is not unique since for any antiderivative F (x) of f(x), F (x) + C is also an antiderivative for all integration constants C 2 R. We will use the notation Z f(x) dx = F (x) + C called the indefinite integral of f to denote the family of all antiderivatives of f. 1.1 Table of Integrals (omitting the integration constant) Elementary Functions Z cot(x) dx = ln j sin(x)j (10) Z 1 xa dx = · xa+1; a 6= −1 (1) a + 1 Z Z 1 dx = ln jxj (2) sec(x) dx = ln j tan(x) + sec(x)j (11) x Exponential and Logarithms Z Z csc(x) dx = − ln j cot(x) + csc(x)j (12) ex dx = ex (3) Rational Functions Z ln(x) dx = x ln(x) − x (4) Z 1 dx = tan−1(x)(13) 1 + x2 Z ax ax dx = (5) Z 1 ln(a) p dx = sin−1(x)(14) 1 − x2 Z x ln(x) − x log (x) dx = (6) Z 1 a ln(a) p dx = sec−1(jxj)(15) x x2 − 1 Trigonometric Functions Hyperbolic Functions Z Z sin(x) dx = − cos(x)(7) sinh(x) dx = cosh(x)(16) Z Z cos(x) dx = sin(x)(8) cosh(x) dx = sinh(x)(17) Z Z tan(x) dx = − ln j cos(x)j (9) tanh(x) dx = ln j cosh(x)j (18) 1.2 Basic Property For constants a; b 2 R and integrable functions f and g, we have Linearity: Z Z Z (af(x) + bg(x)) dx = a f(x) dx + b g(x) dx: We will introduce more basic properties in the coming weeks.