Music Scene Gentrification in the Lower East Side and Williamsburg Joshua Solomon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

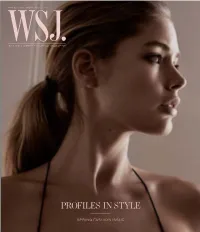

Profiles in Style

PROFILES IN STYLE spring fashion issue Collection RALPHLAURENCOLLECTION.COM 888.475.7674 FLÂNEUR FOREVER 1-800-441-4488 Hermes.com CHANEL BOUTIQUES 800.550.0005 chanel.com ©2015 CHANEL®, Inc. B® Reine de Naples Collection in every woman is a queen BREGUET BOUTIQUES – NEW YORK 646 692-6469 – BEVERLY HILLS 310 860-9911 BAL HARBOUR 305 866-1061 – LAS VEGAS 702 733-7435 – TOLL FREE 877-891-1272 – WWW.BREGUET.COM CAROLINAHERRERA.COM 888.530.7660 © 2015 Estée Lauder Inc. DRIVEN BY DESIRE esteelauder.com NEW. PURE COLOR ENVY SHINE Sculpt. Hydrate. Illuminate. On Carolyn: Empowered NEW ORIGINAL HIGH-IMPACT CREME AND NEW SHINE FINISH BALENCIAGA.COM 870 MADISON AVENUE NEW YORK MAXMARA.COM 1.866.MAX MARA BOUTIQUES 1-888-782-6357 OSCARDELARENTA.COM H® AC CO 5 01 ©2 Coach Dreamers Chloë Grace Moretz/ Actress Coach Swagger 27 in patchwork floral Fluff Jacket in pink coach.com Advertisement EVENTS HOLIDAY LUNCH NewYOrk,NY|12.1.14 On Monday,December 1, WSJ. Magazine hosted its annual holiday luncheon at Le Bernardin Privé in New York. The event welcomed WSJ. Magazine’seditorial and advertising partners and celebrated their 2014 collaborations. Publisher Anthony Cenname toasted WSJ. Mag’sstrongest year in history and stirred excitement about the new year ahead. Photos by Kelly Taub/BFAnyc.com Robert Chavez, Heather Vandenberghe, Shauna Brook Frank Furlan, Rosita Wheeler, Lynn Reid Brad Nelson, Tate Magner Colleen Caslin, Anthony Cenname Jon Spring, Arwa Al Shehhi Desiree Gallas Sandeep Dasgupta, Kevin Dailey Alberto Apodaca, Julia Erdman Jenny Oh, Dana Drehwing, Maria Canale Kevin Harter, Jason Weisenfeld, Vira Capeci Follow @WSJnoted or visit us at wsjnoted.com ©2015Dow Jones &Company,InC.all RIghts ReseRveD.6ao1412 ART DIR: PAUL MARCIANO PH: DAVID BELLEMERE GUESS?©2015 women’s style march 2015 54 EDITOR’S LETTER 58 ON THE COVER 60 CONTRIBUTORS 62 COLUMNISTS on Ambition 65 THE WSJ. -

Unobtainium-Vol-1.Pdf

Unobtainium [noun] - that which cannot be obtained through the usual channels of commerce Boo-Hooray is proud to present Unobtainium, Vol. 1. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We invite you to our space in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where we encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections by appointment or chance. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Please contact us for complete inventories for any and all collections. The Flash, 5 Issues Charles Gatewood, ed. New York and Woodstock: The Flash, 1976-1979. Sizes vary slightly, all at or under 11 ¼ x 16 in. folio. Unpaginated. Each issue in very good condition, minor edgewear. Issues include Vol. 1 no. 1 [not numbered], Vol. 1 no. 4 [not numbered], Vol. 1 Issue 5, Vol. 2 no. 1. and Vol. 2 no. 2. Five issues of underground photographer and artist Charles Gatewood’s irregularly published photography paper. Issues feature work by the Lower East Side counterculture crowd Gatewood associated with, including George W. Gardner, Elaine Mayes, Ramon Muxter, Marcia Resnick, Toby Old, tattooist Spider Webb, author Marco Vassi, and more. -

The Direct Action Politics of US Punk Collectives

DIY Democracy 23 DIY Democracy: The Direct Action Politics of U.S. Punk Collectives Dawson Barrett Somewhere between the distanced slogans and abstract calls to arms, we . discovered through Gilman a way to give our politics some application in our actual lives. Mike K., 924 Gilman Street One of the ideas behind ABC is breaking down the barriers between bands and people and making everyone equal. There is no Us and Them. Chris Boarts-Larson, ABC No Rio Kurt Cobain once told an interviewer, “punk rock should mean freedom.”1 The Nirvana singer was arguing that punk, as an idea, had the potential to tran- scend the boundaries of any particular sound or style, allowing musicians an enormous degree of artistic autonomy. But while punk music has often served as a platform for creative expression and symbolic protest, its libratory potential stems from a more fundamental source. Punk, at its core, is a form of direct action. Instead of petitioning the powerful for inclusion, the punk movement has built its own elaborate network of counter-institutions, including music venues, media, record labels, and distributors. These structures have operated most notably as cultural and economic alternatives to the corporate entertainment industry, and, as such, they should also be understood as sites of resistance to the privatizing 0026-3079/2013/5202-023$2.50/0 American Studies, 52:2 (2013): 23-42 23 24 Dawson Barrett agenda of neo-liberalism. For although certain elements of punk have occasion- ally proven marketable on a large scale, the movement itself has been an intense thirty-year struggle to maintain autonomous cultural spaces.2 When punk emerged in the mid-1970s, it quickly became a subject of in- terest to activists and scholars who saw in it the potential seeds of a new social movement. -

God in Chinatown

RELIGION, RACE, AND ETHNICITY God in Chinatown General Editor: Peter J. Paris Religion and Survival in New York's Public Religion and Urban Transformation: Faith in the City Evolving Immigrant Community Edited by Lowell W. Livezey Down by the Riverside: Readings in African American Religion Edited by Larry G. Murphy New York Glory: Kenneth ]. Guest Religions in the City Edited by Tony Carnes and Anna Karpathakis Religion and the Creation of Race and Ethnicity: An Introduction Edited by Craig R. Prentiss God in Chinatown: Religion and Survival in New York's Evolving Immigrant Community Kenneth J. Guest 111 New York University Press NEW YORK AND LONDON NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS For Thomas Luke New York and London www.nyupress.org © 2003 by New York University All rights reserved All photographs in the book, including the cover photos, have been taken by the author. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Guest, Kenneth J. God in Chinatown : religion and survival in New York's evolving immigrant community I Kenneth J. Guest. p. em.- (Religion, race, and ethnicity) Includes bibliographical references (p. 209) and index. ISBN 0-8147-3153-8 (cloth) - ISBN 0-8147-3154-6 (paper) 1. Immigrants-Religious life-New York (State)-New York. 2. Chinese Americans-New York (State )-New York-Religious life. 3. Chinatown (New York, N.Y.) I. Title. II. Series. BL2527.N7G84 2003 200'.89'95107471-dc21 2003000761 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Chinatown and the Fuzhounese 37 36 Chinatown and the Fuzhounese have been quite successful, it also includes many individuals who are ex tremely desperate financially and emotionally. -

The Decline of New York City Nightlife Culture Since the Late 1980S

1 Clubbed to Death: The Decline of New York City Nightlife Culture Since the Late 1980s Senior Thesis by Whitney Wei Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of BA Economic and Social History Barnard College of Columbia University New York, New York 2015 2 ii. Contents iii. Acknowledgement iv. Abstract v. List of Tables vi. List of Figures I. Introduction……………………………………………………………………7 II. The Limelight…………………………………………………………………12 III. After Dark…………………………………………………………………….21 a. AIDS Epidemic Strikes Clubland……………………..13 b. Gentrification: Early and Late………………………….27 c. The Impact of Gentrification to Industry Livelihood…32 IV. Clubbed to Death …………………………………………………………….35 a. 1989 Zoning Changes to Entertainment Venues…………………………36 b. Scandal, Vilification, and Disorder……………………………………….45 c. Rudy Giuliani and Criminalization of Nightlife………………………….53 V. Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………60 VI. Bibliography………………………………………………………………..…61 3 Acknowledgement I would like to take this opportunity to thank Professor Alan Dye for his wise guidance during this thesis process. Having such a supportive advisor has proven indispensable to the quality of this work. A special thank you to Ian Sinclair of NYC Planning for providing key zoning documents and patient explanations. Finally, I would like to thank the support and contributions of my peers in the Economic and Social History Senior Thesis class. 4 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to investigate the impact of city policy changes and the processes of gentrification on 1980s nightlife subculture in New York City. What are important to this work are the contributions and influence of nightlife subculture to greater New York City history through fashion, music, and art. I intend to prove that, in combination with the city’s gradual revanchism of neighborhood properties, the self-destructive nature of this after-hours sector has led to its own demise. -

Ramones 2002.Pdf

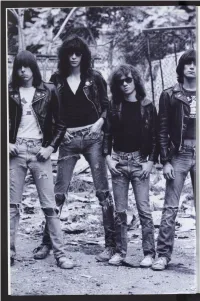

PERFORMERS THE RAMONES B y DR. DONNA GAINES IN THE DARK AGES THAT PRECEDED THE RAMONES, black leather motorcycle jackets and Keds (Ameri fans were shut out, reduced to the role of passive can-made sneakers only), the Ramones incited a spectator. In the early 1970s, boredom inherited the sneering cultural insurrection. In 1976 they re earth: The airwaves were ruled by crotchety old di corded their eponymous first album in seventeen nosaurs; rock & roll had become an alienated labor - days for 16,400. At a time when superstars were rock, detached from its roots. Gone were the sounds demanding upwards of half a million, the Ramones of youthful angst, exuberance, sexuality and misrule. democratized rock & ro|ft|you didn’t need a fat con The spirit of rock & roll was beaten back, the glorious tract, great looks, expensive clothes or the skills of legacy handed down to us in doo-wop, Chuck Berry, Clapton. You just had to follow Joey’s credo: “Do it the British Invasion and surf music lost. If you were from the heart and follow your instincts.” More than an average American kid hanging out in your room twenty-five years later - after the band officially playing guitar, hoping to start a band, how could you broke up - from Old Hanoi to East Berlin, kids in full possibly compete with elaborate guitar solos, expen Ramones regalia incorporate the commando spirit sive equipment and million-dollar stage shows? It all of DIY, do it yourself. seemed out of reach. And then, in 1974, a uniformed According to Joey, the chorus in “Blitzkrieg Bop” - militia burst forth from Forest Hills, Queens, firing a “Hey ho, let’s go” - was “the battle cry that sounded shot heard round the world. -

Notes CHAPTER 1 6

notes CHAPTER 1 6. The concept of the settlement house 1. Mario Maffi, Gateway to the Promised originated in England with the still extant Land: Ethnic Cultures in New York’s Lower East Tonybee Hall (1884) in East London. The Side (New York: New York University Press, movement was tremendously influential in 1995), 50. the United States, and by 1910 there were 2. For an account of the cyclical nature of well over four hundred settlement houses real estate speculation in the Lower East Side in the United States. Most of these were in see Neil Smith, Betsy Duncan, and Laura major cities along the east and west coasts— Reid, “From Disinvestment to Reinvestment: targeting immigrant populations. For an over- Mapping the Urban ‘Frontier’ in the Lower view of the settlement house movement, see East Side,” in From Urban Village to East Vil- Allen F. Davis, Spearheads for Reform: The lage: The Battle for New York’s Lower East Side, Social Settlements and the Progressive Movement, ed. Janet L. Abu-Lughod, (Cambridge, Mass.: 1890–1914 (New York: Oxford University Blackwell Publishers, 1994), 149–167. Press, 1967). 3. James F. Richardson, “Wards,” in The 7. The chapter “Jewtown,” by Riis, Encyclopedia of New York City, ed. Kenneth T. focuses on the dismal living conditions in this Jackson (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University ward. The need to not merely aid the impover- Press, 1995), 1237. The description of wards in ished community but to transform the physi- the Encyclopedia of New York City establishes cal city became a part of the settlement work. -

WS Folk Riot Booklet

1 playing “cover” songs as diverse and influential Meanwhile, due to our leftist leanings and omni- 10,000 Watts of Folk as the Statler Brothers’ “Flowers on the Wall,” presence in the Village, activist Abbie Hoffman 1. I AIN’T KISSING YOU (0:54) by Trixie A. Balm met with we three Squares and co-wrote a theme VANGUARD STUDIOS, NYC (aka Lauren Agnelli) Alas, that deal fell through. though the song for his new live radio show, “Radio Free September 1985 sessions remain, with Tom, Lauren, Bruce and Billy U.S.A.”: heard here for the first time since the playing “cover” songs as diverse and influential debut show back in 1986 at the Village Gate. By 1985, we Washington Squares, having worked, as the Statler Brothers’ “Flowers on the Wall,” Vanguard, an important folk label during the ‘50s sang and played our way through the ‘80’s Richard Hell’s “Love Comes in Spurts,” Lou Reed’s At last, in 1987, Gold Castle/Polydor records who and ‘60s was sold in 1985. Vanguard sold off their Greenwich Village folk scene fray, were ready to “Sweet Jane,” and Johnny Thunders’ “Chinese Rocks.” DID sign us to a deal found the perfect sound classical collection and reissued their folk and then record. The record company interest was there though producer Mitch Easter (of the group Let’s started looking for new acts. With a bunch of well and soon serious recording contracts would dangle Having somewhat mastered those formative nuggets, Active— he also recorded REM’s initial sessions) known original Vanguard producers in the control room: before our fresh (very fresh!) young smirks. -

Compatible Infill Design Principles for New Construction in Oregon’S Historic Districts

SPECIAL REPORT Compatible Infill Design Principles for New Construction in Oregon’s Historic Districts Recommendations from Restore Oregon based on the 2011 Preservation Roundtable Page 2 Restore Oregon Special Report: Compatible Infill Design Purpose 2 2011 Preservation Why Good Infill Matters 3 Roundtable Process The Value of Oregon’s Historic Districts 4 Topic defined Fall 2010 Advising, Encouraging, and Regulating 5 Research and planning What Makes a Good Guideline? 7 Spring 2011 Principles for Infill Construction 8 Regional Workshop I The Dalles Strategies for Implementation 11 June 25, 2011 Acknowledgements and Notes 11 Regional Workshop II Ashland July 8, 2011 Cover photo: Drew Nasto © 2011 Restore Oregon. All rights reserved. Regional Workshop III Portland August 18, 2011 Online Survey Early September 2011 Report Released October 13, 2011 The Preservation Roundtable was organized by Restore Oregon, formerly the Historic Preservation League of Oregon, to bring together diverse stakeholders to analyze and develop solutions to the underlying issues that stymie preservation efforts. The inaugural topic in 2010 was “Healthy Historic Districts in a Changing World—Compatibility and Viability.” Nearly one hundred people participated, arriving at nine recommendations published in a report titled Healthy Historic Districts – Solutions to Preserve and Revitalize Oregon’s Historic Downtowns. An electronic copy is available on Restore Oregon’s website. The 2011 Preservation Roundtable focused in on “Design Standards for Compatible Infill,” one of the recommendations from the 2010 report, to provide clarity and consistency for review of new construction projects in historic districts. The principles and approaches to implementation that follow come from the best source: the people that live, work, own property, govern, and build within the state’s 123 National Register historic districts. -

Oral History Interview with Wendy Olsoff and Penny Pilkington, 2009 January 21 and May 22

Oral history interview with Wendy Olsoff and Penny Pilkington, 2009 January 21 and May 22 Funding for this interview was provided by the Widgeon Point Charitable Foundation. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Wendy Olsoff and Penny Pilkington on January 21 and May 22, 2009. The interview took place at in New York, New York, and was conducted by James McElhinney for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Funding for this interview was provided by a grant from the Widgeon Point Charitable Foundation. Wendy Olsoff, Penny Pilkington, and James McElhinney have reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview JAMES McELHINNEY: This is James McElhinney speaking with Penny Pilkington and Wendy Olstroff. PENNY PILKINGTON: Olsoff. O-L-S-O-F-F. MR. McELHINNEY: Olsoff? WENDY OLSOFF: Right. MR. McELHINNEY: At 432 Lafayette Street in New York, New York, on January 21, 2009. So for the transcriber, I’m going to ask you to just simply introduce yourselves so that the person who is writing out the interview will be able to identify— [END OF DISC 1, TRACK 1.] MR. McELHINNEY: —who’s who by voice. -

Music 5364 Songs, 12.6 Days, 21.90 GB

Music 5364 songs, 12.6 days, 21.90 GB Name Album Artist Miseria Cantare- The Beginning Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Pt. 2 Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Bleed Black Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Silver and Cold Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Dancing Through Sunday Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Girl's Not Grey Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Death of Seasons Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Great Disappointment Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Paper Airplanes (Makeshift Wings) Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. This Celluloid Dream Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. But Home is Nowhere Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Hurricane Of Pain Unknown A.L.F. The Weakness Of The Inn Unknown A.L.F. I In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The World Beyond In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Acolytes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Thousand Suns In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Into The Ashes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Smoke and Mirrors In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Semblance Of Life In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Empyrean:Into The Cold Wastes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Floods In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The Departure In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams From A Buried Heart Legend Abigail Williams Like Carrion Birds Legend Abigail Williams The Conqueror Wyrm Legend Abigail Williams Watchtower Legend Abigail Williams Procession Of The Aeons Legend Abigail Williams Evolution Of The Elohim Unknown Abigail Williams Forced Ingestion Of Binding Chemicals Unknown Abigail -

WC PUBLIC BROOKLYN 1 Name Location Open Year- Round

WC PUBLIC BROOKLYN Open Year- Name Location Accessible Round 100% Playground 100% Playground Yes Glenwood Road, East 100 & East 101 streets Albemarle Playground Albemarle Park Yes Albermarle Road & Dahill Road Albert J. Parham Playground Albert J. Parham Playground Adelphi Street, Clermont, DeKalb & Yes Willoughby avenues American Playground American Playground Yes Noble, Franklin Milton Streets Asser Levy Park Asser Levy Park Boardwalk, Surf, Sea Breeze avenues, Ocean Yes Parkway Asser Levy Park Asser Levy Park (Performance Boardwalk, Surf, Sea Breeze avenues, Ocean Yes Space) Parkway Bartlett Playground Bartlett Playground Yes Bartlett Street & Throop Avenue Bayview Playground Bayview Playground Yes Seaview Avenue & East 99 Street Bedford Playground Bedford Playground Bedford Avenue & South 9 Street, Division Yes Avenue Benson Playground Benson Playground Yes Bath Avenue between Bay 22 & Bay 23 streets Bensonhurst Park Bensonhurst Park Gravesend Bay, 21 & Cropsey avenues, Bay Yes Parkway Betsy Head Park Betsy Head Playground Livonia, Dumont, Hopkinson, Blake avenues, Yes Strauss Street Betsy Head Park Betsy Head Playground Livonia, Dumont, Hopkinson, Blake avenues, Yes (Administration Building) Strauss Street Bildersee Playground Bildersee Playground Flatlands Avenue between East 81 & East 82 Yes streets Bill Brown Playground Bedford Avenue, Avenue X to Avenue Y, E Bill Brown Memorial Playground Yes 24 Street This facility is currently closed. Details Breukelen Ballfields Breukelen Playground Yes Louisiana & Flatlands Avenue Brevoort Playground Brevoort Playground Yes Ralph Avenue & Chauncy Street Bridge Park 2 Bridge & Prospect streets Yes 1 2 [Tapez le texte] Open Year- Name Location Accessible Round Brower Park Brower Park Brooklyn, St. Mark's, Kingston avenues, Park Yes Place Brower Park Brower Park (Museum) Brooklyn, St.