Large-Scale Trade in Legally Protected Marine Mollusc Shells from Java and Bali, Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animal Creativity and Innovation

CHAPTER 4 Cetacean Innovation Eric M. Patterson1 and Janet Mann1,2 1Department of Biology, Georgetown University, Washington DC, USA 2Department of Psychology, Georgetown University, Washington DC, USA A cloud of cigarette smoke was once deliberately released against the glass as Dolly was looking in through the viewing port. The observer was astonished when the animal immediately swam off to its mother, returned and released a mouthful of milk which engulfed her head, giving much the same effect as had the cigarette smoke. (Tayler & Saayman, 1973) Commentary on Chapter 4: Proto-c Creativity? Vlad Petre Glaveanu˘ Aalborg University, Department of Communication and Psychology, Aalborg, Denmark INTRODUCTION Dolly’s “milk smoking” is just one of many fascinating behaviors Tayler and Saayman observed in Indian Ocean bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) at the Port Elizabeth Oceanarium in South Africa in the 1970s. Not only did Dolly parade her impressive imitation abilities and potential analogous reasoning, she gave us a peek into her creative mind. But of what use would such creative behavior be in the wild? Milk smoking would certainly be maladaptive for a young, hungry calf, but could similar creative abilities be beneficial, say, for exploiting new Animal Creativity and Innovation. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800648-1.00004-8 73 © 2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 74 4. CETACEAN INNOVATION resources or obtaining mates? Only recently have such questions been the subject of empirical work in ethology. To date, most data on animal innovation come from primates and birds. After scouring the literature for anecdotal observations of novel behavior and carefully controlling for confounding factors (e.g., phy- logeny, research effort, observation biases, etc.), Laland, Lefebvre, Reader, Sol, and colleagues have provided some of the most intriguing data on animal creativity and innovation (Lefebvre, Reader, & Sol, 2013; Lefebvre, Whittle, Lascaris, & Finkelstein, 1997; Reader & Laland, 2001). -

Structure and Function of the Digestive System in Molluscs

Cell and Tissue Research (2019) 377:475–503 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-019-03085-9 REVIEW Structure and function of the digestive system in molluscs Alexandre Lobo-da-Cunha1,2 Received: 21 February 2019 /Accepted: 26 July 2019 /Published online: 2 September 2019 # Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract The phylum Mollusca is one of the largest and more diversified among metazoan phyla, comprising many thousand species living in ocean, freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems. Mollusc-feeding biology is highly diverse, including omnivorous grazers, herbivores, carnivorous scavengers and predators, and even some parasitic species. Consequently, their digestive system presents many adaptive variations. The digestive tract starting in the mouth consists of the buccal cavity, oesophagus, stomach and intestine ending in the anus. Several types of glands are associated, namely, oral and salivary glands, oesophageal glands, digestive gland and, in some cases, anal glands. The digestive gland is the largest and more important for digestion and nutrient absorption. The digestive system of each of the eight extant molluscan classes is reviewed, highlighting the most recent data available on histological, ultrastructural and functional aspects of tissues and cells involved in nutrient absorption, intracellular and extracellular digestion, with emphasis on glandular tissues. Keywords Digestive tract . Digestive gland . Salivary glands . Mollusca . Ultrastructure Introduction and visceral mass. The visceral mass is dorsally covered by the mantle tissues that frequently extend outwards to create a The phylum Mollusca is considered the second largest among flap around the body forming a space in between known as metazoans, surpassed only by the arthropods in a number of pallial or mantle cavity. -

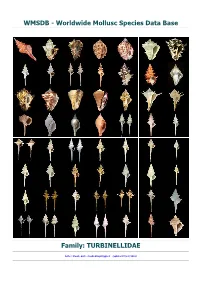

Turbinellidae

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINELLIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: CAENOGASTROPODA-HYPSOGASTROPODA-NEOGASTROPODA-MURICOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINELLIDAE Swainson, 1835 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=276, Genus=12, Subgenus=4, Species=91, Subspecies=13, Synonyms=155, Images=87 aapta , Coluzea aapta M.G. Harasewych, 1986 acuminata, Turbinella acuminata L.C. Kiener, 1840 - syn of: Latirus acuminatus (L.C. Kiener, 1840) aequilonius, Fulgurofusus aequilonius A.V. Sysoev, 2000 agrestis, Turbinella agrestis H.E. Anton, 1838 - syn of: Nicema subrostrata (J.E. Gray, 1839) aldridgei , Vasum aldridgei G.W. Nowell-Usticke, 1969 - syn of: Attiliosa aldridgei (G.W. Nowell-Usticke, 1969) altocanalis , Coluzea altocanalis R.K. Dell, 1956 amaliae , Turbinella amaliae H.C. Küster & W. Kobelt, 1874 - syn of: Hemipolygona amaliae (H.C. Küster & W. Kobelt, 1874) angularis , Coluzea angularis (K.H. Barnard, 1959) angularis , Turbinella angularis L.A. Reeve, 1847 - syn of: Leucozonia nassa (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) angularis riiseana , Turbinella angularis riiseana H.C. Küster & W. Kobelt, 1874 - syn of: Leucozonia nassa (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) angulata , Turbinella angulata (J. Lightfoot, 1786) annulata, Syrinx annulata P.F. Röding, 1798 - syn of: Pustulatirus annulatus (P.F. Röding, 1798) aptos , Columbarium aptos M.G. Harasewych, 1986 - syn of: Coluzea aapta M.G. Harasewych, 1986 ardeola , Vasum ardeola A. Valenciennes, 1832 - syn of: Vasum caestus (W.J. Broderip, 1833) armatum , Vasum armatum (W.J. Broderip, 1833) armigera , Tudivasum armigera A. Adams, 1855 - syn of: Tudivasum armigerum (A. Adams, 1856) armigera , Turbinella armigera J.B.P.A. -

The Snail & the Whale

T h e S n a i l & t h e W h a l e S T U D Y G U I D E . V I R T U A L P E R F O R M A N C E S 2 0 2 0 - 2 1 T I L L E S C E N T E R F O R T H E P E R F O R M I N G A R T S I S L O N G I S L A N D ’ S P R E M I E R C O N C E R T H A L L . For 39 years, Tilles Center has been host to more We thank you for supporting Tilles Center during than 70 performances each season by world- the COVID-19 Pandemic and providing this renowned artists in music, theater and virtual program for your students . We can't wait dance. Tilles Center’s newly renovated Concert Hall, to welcome you back IN PERSON! scheduled to open in the spring of 2021, seats over 2,200 guests and features orchestral performances, fully-staged operas, ballets and modern dance, along with Broadway shows, and all forms of music, Tilles Center’s Education Programs are made possible, in part, dance and theater from around the world. with funds from the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. Thanks to the generous support of Eric and Sandra Arts Education programs are made possible, in Krasnoff, the Krasnoff Theater, formerly part, by the Gilbert and Rose Tilles Endowment for Arts Education. -

Gastropod Evidence Against the Early Triassic Lilliput Effect: REPLY

Gastropod evidence against the Early Triassic Lilliput effect: REPLY REPLY: doi:10.1130/G31765Y.1 Cretaceous and whose members reach large sizes. Such gastropods were not present in the Early Mesozoic. Using Syrinx as a reference, the vast Arnaud Brayard1, Alexander Nützel2, Andrzej Kaim2, 3, Gilles majority of Phanerozoic gastropod faunas would fall into the Lilliput cat- Escarguel4, Michael Hautmann5, Daniel A. Stephen6, Kevin G. egory. Moreover, the absence of “giant” taxa in the Early Triassic fos- Bylund7, Jim Jenks8, and Hugo Bucher5 sil record may well be a preservation artifact due to the generally poorly 1UMR 5561 CNRS Biogéosciences, Université de Bourgogne, documented fossil record of that time interval. 21000 Dijon, France The reported maximum sizes of Permian (but not Late Permian) and 2Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und Geologie, Middle Triassic gastropods does exceed that of Early Triassic gastropods, 80333 Munich, Germany but this might be a purely stochastic effect due to the rather low Early 3Instytut Paleobiologii PAN, PL-00-818 Warsaw, Poland Triassic species diversity (<100 species known) and specimen abundance. 4UMR 5125 CNRS PEPS, Université Lyon 1, 69622 Villeurbanne Usually, log-normal size distributions are highly right-skewed, making Cedex, France larger species much rarer than smaller ones (independent of species’ rela- 5Paläontologisches Institut und Museum, Universität Zürich, tive abundance, negatively correlated with body size). We ran sub-sam- 8006 Zurich, Switzerland pling Monte Carlo analyses of Bouchet et al.’s (2002) size distribution of 6Department of Earth Science, Utah Valley University, Orem, Utah 2581 extant mollusc species based on random generation of sets of 100 84058, USA species (ca. -

Cop17 Inf. 2 (English Only / Únicamente En Inglés / Seulement En Anglais)

Original language: English CoP17 Inf. 2 (English only / Únicamente en inglés / Seulement en anglais) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Seventeenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Johannesburg (South Africa), 24 September – 5 October 2016 TRAFFIC Report April 2016 AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE TRADE OF NAUTILUS This document has been submitted by the United States of America, in relation to amendment proposal * CoP17 Prop. 48 on Inclusion of the Familiy Nautilidae in Appendix II . * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. CoP17 Inf. 2 – p. 1 TRAFFIC AN INVESTIGATIONINVESTIGATION INTO INTO THE THE TRADE TRADEOF NAUTILUS OF NAUTILUS REPORT APRIL 2016 AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE TRADE OF NAUTILUS ©Jürgen Freund and WWF/TRAFFIC APRIL 2016 TRAFFIC/WWF Nautilus Trade Investigation 1 ©TRAFFIC/WWF. 2016 All rights reserved. This material has no commercial purposes. The reproduction of the material contained in this publication is prohibited for sale or other commercial purposes. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit TRAFFIC / WWF as copyright owner. The document was financed by US Fish and Wildlife Service and US NOAA Fisheries. The opinions, findings and conclusions stated herein are those of the author[s] and do not necessarily reflect those of the donor and partner organizations listed in the acknowledgements. -

Shell's Field Guide C.20.1 150 FB.Pdf

1 C.20.1 Human beings have an innate connection and fascination with the ocean & wildlife, but still we know more about the moon than our Oceans. so it’s a our effort to introduce a small part of second largest phylum “Mollusca”, with illustration of about 600 species / verities Which will quit useful for those, who are passionate and involved with exploring shells. This database made from our personal collection made by us in last 15 years. Also we have introduce website “www.conchology.co.in” where one can find more introduction related to our col- lection, general knowledge of sea life & phylum “Mollusca”. Mehul D. Patel & Hiral M. Patel At.Talodh, Near Water Tank Po.Bilimora - 396321 Dist - Navsari, Gujarat, India [email protected] www.conchology.co.in 2 Table of Contents Hints to Understand illustration 4 Reference Books 5 Mollusca Classification Details 6 Hypothetical view of Gastropoda & Bivalvia 7 Habitat 8 Shell collecting tips 9 Shell Identification Plates 12 Habitat : Sea Class : Bivalvia 12 Class : Cephalopoda 30 Class : Gastropoda 31 Class : Polyplacophora 147 Class : Scaphopoda 147 Habitat : Land Class : Gastropoda 148 Habitat :Freshwater Class : Bivalvia 157 Class : Gastropoda 158 3 Hints to Understand illustration Scientific Name Author Common Name Reference Book Page Serial No. No. 5 as Details shown Average Size Species No. For Internal Ref. Habitat : Sea Image of species From personal Land collection (Not in Scale) Freshwater Page No.8 4 Reference Books Book Name Short Format Used Example Book Front Look p-Plate No.-Species Indian Seashells, by Dr.Apte p-29-16 No. -

Midden Formation and Marine Specialisation at Goemu Village, Mabuyag, Torres Strait, Before and After European Contact

Memoirs of the Queensland Museum | Culture Volume 8 Part 2 Goemulgaw Lagal: Cultural and Natural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait Edited by Ian J. McNiven and Garrick Hitchcock Minister: Annastacia Palaszczuk MP, Premier and Minister for the Arts CEO: Suzanne Miller, BSc(Hons), PhD, FGS, FMinSoc, FAIMM, FGSA , FRSSA Editor in Chief: J.N.A. Hooper, PhD Editors: Ian J. McNiven, PhD FSA FAHA and Garrick Hitchcock, PhD FLS FRGS Issue Editor: Geraldine Mate, PhD PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD 2015 © Queensland Museum PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone: +61 (0) 7 3840 7555 Fax: +61 (0) 7 3846 1226 Web: qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 VOLUME 8 IS COMPLETE IN 2 PARTS COVER Image on book cover: Pearlshelling station at Panay, Mabuyag, 1890s. Photographer unknown (Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology: N23274.ACH2). NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the CEO. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed on the Queensland Museum website qm.qld.gov.au A Queensland Government Project Design and Layout: Tanya Edbrooke, Queensland Museum Printed by Watson, Ferguson & Company Midden formation and marine specialisation at Goemu village, Mabuyag, Torres Strait, before and after European contact Ian J. -

Adec Preview Generated PDF File

Records of the Western Allstralian Mllselllll Supplement No. 66: 247-291 (2004). Diversity and distribution of subtidal benthic molluscs from the Dampier Archipelago, Western Australia; results of the 1999 dredge survey (DA2/99) John D. Taylor and Emily A. Glover Department of Zoology, The Natural History Museum, London SW7 5BD, U.K. email: [email protected] [email protected] Abstract - From a dredge survey of the subtidal fauna of the Dampier Archipelago a total of 422 species of macromolluscs was identified, comprising 227 gastropods, 188 bivalves, four scaphopods and three chitons. Most species were uncommon but abundant taxa included the bivalves Melaxinaea vitrea, Corbllla fZlIIlcata and C. crassa and the gastropods Herpetopoma atrata and Xenophora solarioides. Community analysis identified eight molluscan assemblages, reflecting the varied and patchy nature of the substrates that ranged from muds and silts to coarse sands, gravel, rubble and rocks. The most species-rich stations were those located inshore at water depths <10 m. These muddy stations were also notable for the diversity and abundance of suspension-feeding bivalves. Most of the mollusc species identified are distributed widely around tropical Australia and the Indo-West Pacific but a few are endemic to northwestern Australia, including the newly described lucinid bivalve Lamellolllcina pilbara. INTRODUCTION parts of the world. Studies of latitudinal gradients Although the northwestern Australian shelf is of in molluscan diversity usually focus on well outstanding biological interest for its suspected high documented continental margins such as the diversity and the relatively high numbers of eastern Pacific coast of North America (Roy, endemic taxa, the subtidal molluscan fauna is Jablonski and Valentine, 2001; Valentine, Roy and poorly known. -

80 Mile Beach, 1999 - Preliminary Research Report

80 mile beach, 1999 - preliminary research report Preliminary Research Report Anna Plains Benthic Invertebrate and bird Mapping 1999 ANNABIM-99 by Theunis Piersma (Netherlands Institute for Sea Research - NIOZ and University of Groningen) Marc Lavaleye (Netherlands Institute for Sea Research - NIOZ) & Grant Pearson (Western Australian Department of Conservation and Land Management - CALM) Maps by Michelle Crean (Curtin University of Technology) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Study area and methods http://www.yogibob.com/80mile/annabim.html (1 of 11)4/04/2007 1:39:05 PM 80 mile beach, 1999 - preliminary research report 3. Preliminary results 4.Management Implications 5.Conclusions 6. Acknowledgements 1. Introduction Among the wetland wonders of the northern part of Western Australia, the intertidal foreshore of Anna Plains Station, representing the northernmost 80 km of Eighty Mile Beach, stands out for its importance as a key nonbreeding area used by arctic-breeding shorebirds. Along Eighty Mile Beach, about half a million roosting shorebirds have been counted in recent years (414,000 in October 1998; C.D.T. Minton et al. pers. comm.). The great majority of these birds occur at the beach along Anna Plains Station, 25 to 75 km south of Cape Missiessy. Although it is widely agreed that most species (other than Little Curlew Numenius minutus and Oriental Plover Charadrius veredus) use the intertidal foreshore as their feeding area, nobody has hitherto studied either the feeding distribution and behaviour of shorebirds, nor has anybody studied the nature of their food resources along Eighty Mile Beach. We really need such knowledge if we are to conserve the immense and internationally shared natural values of Eighty Mile Beach, and to find informed compromises between the increasing use of beach and foreshore by the soaring human population in the Kimberley Region and their use by the beasts and the birds. -

Fish Tales the Harvard Museum of Natural History in November Unveiled Its New Exhibition on Marine Life

JOHNJOHN HARVard’s JOURNAL Fish Tales The Harvard Museum of Natural History in November unveiled its new exhibition on marine life. The centerpiece (shown here), a cleverly lit diorama, depicts New England coastal waters from the shallows to the depths: a pioneering way to educate and entrance visitors without penning liv- Photograph by LesJim HarrisonVants Aerial Photos/courtesy of Harvard Art Museums Harvard Magazine 17 Reprinted from Harvard Magazine. For more information, contact Harvard Magazine, Inc. at 617-495-5746 JOHN HARVARD'S JOURNAL ing specimens in a small habitat. That dis- ture (focusing on jel- play neatly complements the adjacent gal- lies), and of Harvard lery on the region’s forests, and closes what scientists’ work. They Visit harvardmag.com to see more specimens curators describe as a “gaping hole” in the will likely like the huge from the marine exhibitions, which have underrepresented Australian trumpet exhibition. Earth’s aquatic environment and the stag- shell (Syrinx aruanus, a gering biodiversity it supports. type of snail), and be thrilled or repelled A few hundred mounted specimens in by the giant isopod (Bathynomus giganteus, surrounding cases (from the millions of a crustacean) at rest in its jar. What par- molluscs and fish among the compara- ent could resist the vivid orange lion’s paw tive zoology holdings) give a sense of evo- scallop (Nodipecten nodosus)—or withhold a ON lution, species variation, and the sheer smile at the name of the diminutive Wolf S beauty of nature. Youngsters will enjoy fangbelly (Petroscirtes lupus, one of the Pa- ARRI H M the interactive explanations of nomencla- cific coral-reef combtooth blennies)? JI million—but only because corporate, have closed with The Fiscal Norm foundation, and international underwrit- a surplus of $68 The University’s fiscal year 2015, con- ing rose by more than 10 percent, while million—slightly cluded last June 30 and detailed in the an- federal direct funding decreased by nearly ahead of the fis- nual financial report released in late Octo- $15 million. -

Final Application to Australian Government Department of the Environment and Heritage on the Specimen Shell Managed Fishery

FINAL APPLICATION TO AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT AND HERITAGE ON THE SPECIMEN SHELL MANAGED FISHERY Against the Guidelines for the Ecologically Sustainable Management of Fisheries For Consideration Under Parts 13 and 13A of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 MARCH 2005 DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES, WESTERN AUSTRALIA LOCKED BAG 39, CLOISTERS SQUARE WA 6850 Final Application to the Department of the Environment and Heritage for the Specimen Shells Fishery TABLE OF FIGURES...............................................................................................4 TABLES ....................................................................................................................5 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE APPLICATION ......................................................6 1.1 DESCRIPTION OF INFORMATION PROVIDED ...........................................6 1.2 OVERVIEW OF APPLICATION.......................................................................7 2. BACKGROUND ON THE SSMF ..........................................................................9 2.1 DESCRIPTION OF THE FISHERY...................................................................9 2.2 BIOLOGY OF SPECIMEN SHELL SPECIES.................................................14 2.3 MAJOR ENVIRONMENTS .............................................................................15 2.3.1 PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT...................................................................15 2.3.2 ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT.................................................................15