“Dig If You Will the Picture: Prince's Subversion of Hegemonic Black

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

Teddy Pendergrass - If You Don’T Know Me

TEDDY PENDERGRASS - IF YOU DON’T KNOW ME A Documentary Film by Olivia Lichtenstein 106 Mins This is the story of legendary singer, Teddy Pendergrass, the man who would have been the biggest R&B artist of all time. The story of a childhood in a Philadelphia ghetto; of the murders of his father and first manager; of sex, drugs, money and global fame; of the triumph against injustice; and of the tragic accident that changed his life forever at the age of only 31. His was a life where, despite poverty, racism, and violence, he managed to become one of the first African-American artists to go multi-platinum over and over again. A man who actively championed the rights of black artists when discrimination was rife. A man who in the years after becoming quadriplegic, overcame depression and thoughts of suicide and resumed doing what he loved best - making music. A man who left a priceless legacy after his death, with the music he had made and the people he touched. With revealing and exclusive interviews from the people who knew Teddy best, a soulful soundtrack, and rarely seen archive, it’s a story that all too few really know and which is crying out to be told… Hammersmith Odeon, London, February 3rd 1982. It’s a cold night and fans – almost all of them women - are swarming at the entrance eager to see their idol, the biggest male R&B artist of the time, even bigger then than closest rivals, Marvin Gaye and Barry White. Teddy Pendergrass – the Teddy Bear, the ‘Black Elvis’ - tall and handsome with a distinctive husky soulful voice that could melt a woman’s clothes clean off her body! 'It took Teddy eleven seconds to get to the point with a girl that would take me two dinners and a trip to meet her parents,' says Daniel Markus, one of his managers. -

Black Or White for SAB and Piano

From: “Michael Jackson - Dangerous” Black or White For SAB and Piano by MICHAEL JACKSON Lyrics by MICHAEL JACKSON and BILL BOTTRELL Arranged by KIRBY SHAW Published Under License From Sony/ATV Music Publishing © 1991 Mijac Music This arrangement Copyright © 2013 Mijac Music All Rights Administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC, 8 Music Square West, Nashville, TN 37203 International Copyright Secured All Rights Reserved Authorized for use by Alison Porter NOTICE: Purchasers of this musical file are entitled to use it for their personal enjoyment and musical fulfillment. However, any duplication, adaptation, arranging and/or transmission of this copyrighted music requires the written consent of the copyright owner(s) and of Musicnotes.com. Unauthorized uses are infringements of the copyright laws of the United States and other countries and may subject the user to civil and/or criminal penalties. Ǻ Musicnotes.com Recorded by MICHAEL JACKSON Black or White For SAB and Piano Duration: ca. 3:00 Arranged by Music by KIRBY SHAW MICHAEL JACKSON Words by MICHAEL JACKSON and BILL BOTTRELL Jacksonian rock = 116 q happy squeal Soprano [ mf Alto « · î G b 4 Î Î x Ow! happy squeal Baritone mf F 4 « · î x ] b 4 Î Î N.C. B /F F B 6/F F b b « ê ê « j G b 4 Î Î Ï Ï' Ï Ï Î ÏÏ ÏÏ Ï ú Piano Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï ú {} f F b j Î « j î Î « j nÏ Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï' [ G b · · · F · ] b B /F F B 6/F F B /F F b b b j G b Î Ï Ï Ï Î Ïê ê Ï« Ï ú Î Ï Ï Ï Î Ï Ï ' Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï ú Ï Ï ' Ï Ï {} F 3 b Î « j î « j Î « j Ï Ï bÏ Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï' Ï Ï Ï' Copyright © 1991 Mijac Music This arrangement Copyright © 2013 Mijac Music All Rights Administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC, 8 Music Square West, Nashville, TN 37203 International Copyright Secured All Rights Reserved 4 copies licensed Ǻ Musicnotes.com Authorized for use by: Alison Porter 2 [ G b î Î x · · Ow! F î x · · ] b Î B 6/F F B /F F B 6/F F b b b j j G b Ïê ê Ï« Ï ú Î Ï Ï Ï Î Ïê ê Ï« Ï ú Ï Ï Ï ú Ï Ï ' Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï ú {} F 6 b î Î « j Î « j î « j Ï Ï Ï bÏ Ï Ï Ï Ï' 9 Unis. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Madonna Vogue EP Mp3, Flac, Wma

Madonna Vogue EP mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Vogue EP Country: Japan Released: 1990 Style: House, Garage House MP3 version RAR size: 1802 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1716 mb WMA version RAR size: 1629 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 590 Other Formats: MMF AUD MP3 FLAC AA DXD DMF Tracklist Hide Credits Vogue (12" Version) 1 8:25 Producer – Madonna, Shep Pettibone Vogue (Bette Davis Dub) 2 7:26 Producer – Madonna, Shep Pettibone Vogue (Strike-A-Pose Dub) 3 7:39 Producer – Madonna, Shep Pettibone Hanky Panky (Bare Bones Single Mix) 4 3:52 Producer – Madonna, Patrick LeonardRemix – Kevin Gilbert Hanky Panky (Bare Bottom 12" Mix) 5 6:36 Producer – Madonna, Patrick LeonardRemix – Kevin Gilbert More 6 4:58 Producer – Bill Bottrell, Madonna Companies, etc. Licensed From – Warner Bros. Records (Japan) Inc. Marketed By – Warner Bros. Records Inc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Sire Records Company Copyright (c) – Sire Records Company Phonographic Copyright (p) – WEA International Inc. Copyright (c) – WEA International Inc. Made By – Warner Music Japan Inc. Notes Cover and CD has switched the positions of track 4 & 5 as the single mix precedes the 12" mix. Made in Japan. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (On Obi): 4 988014 736985 Matrix / Runout (Variant 1): WPCP-3698 1A1 TO Matrix / Runout (Variant 2): WPCP-3698 1A2 TO Rights Society: JASRAC Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Vogue (12", 0-21513, 9 21513-0 Madonna Sire, Sire 0-21513, 9 21513-0 US 1990 Maxi) 5439-19851-7, W Vogue (7", Sire, Warner 5439-19851-7, W Madonna France 1990 9851 Single) Bros. -

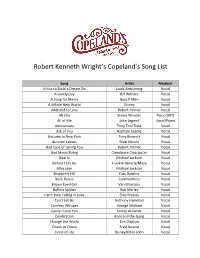

Robert Kenneth Wright's Copeland's Song List

Robert Kenneth Wright’s Copeland’s Song List Song Artist Medium A Kiss to Build a Dream On Louis Armstrong Vocal A Lovely Day Bill Withers Vocal A Song for Mama Boyz II Men Vocal A Whole New World Disney Vocal Addicted to Love Robert Palmer Vocal All I Do Stevie Wonder Piano (WT) All of Me John Legend Vocal/Piano Anniversary Tony Toni Tone Vocal Ask of You Raphael Saadiq Vocal Autumn in New York Tony Bennett Vocal Autumn Leaves Matt Monro Vocal Bad Case of Loving You Robert Palmer Vocal Bad Moon Rising Creedence Clearwater Vocal Beat It Michael Jackson Vocal Before I Let Go Frankie Beverly/Maze Vocal Billie Jean Michael Jackson Vocal Blueberry Hill Fats Domino Vocal Brick House Commodores Vocal Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Vocal Buffalo Soldier Bob Marley Vocal Can’t Help Falling in Love Elvis Presley Vocal Can’t Let Go Anthony Hamilton Vocal Careless Whisper George Michael Vocal Cause I Love You Lenny Williams Vocal Celebration Kool and the Gang Vocal Change the World Eric Clapton Vocal Cheek to Cheek Fred Astaire Vocal Circle of Life Disney/Elton John Vocal Close the Door Teddy Pendergrass Vocal Cold Sweat James Brown Vocal Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Vocal Creepin’ Luther Vandross Vocal Dat Dere Tony Bennett Vocal Distant Lover Marvin Gaye Vocal Don’t Stop Believing Journey Vocal Don’t Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Vocal Don’t You Know That Luther Vandross Vocal Early in the Morning Gap Band Vocal End of the Road Boyz II Men Vocal Every Breath You Take The Police Vocal Feelin’ on Ya Booty R. -

Negrocity: an Interview with Greg Tate

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2012 Negrocity: An Interview with Greg Tate Camille Goodison CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/731 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] NEGROCITY An Interview with Greg Tate* by Camille Goodison As a cultural critic and founder of Burnt Sugar The Arkestra Chamber, Greg Tate has published his writings on art and culture in the New York Times, Village Voice, Rolling Stone, and Jazz Times. All Ya Needs That Negrocity is Burnt Sugar's twelfth album since their debut in 1999. Tate shared his thoughts on jazz, afro-futurism, and James Brown. GOODISON: Tell me about your life before you came to New York. TATE: I was born in Dayton, Ohio, and we moved to DC when I was about twelve, so that would have been about 1971, 1972, and that was about the same time I really got interested in music, collecting music, really interested in collecting jazz and rock, and reading music criticism too. It kinda all happened at the same time. I had a subscription to Rolling Stone. I was really into Miles Davis. He was like my god in the 1970s. Miles, George Clinton, Sun Ra, and locally we had a serious kind of band scene going on. -

Who's Who in Pop Record Production (1995)

WHO'S WHO IN POP RECORD PRODUCTION (1995) The following is a list of PRODUCERS credited on at least one album or one single in the Top Pop 100 Charts or that has been picked in our "Next On The Charts" section so far this year. (Please note that due to computer restraints, PRODUCERS are NOT credited on records that have more than 5 PRODUCERS listed) This listing includes the PRODUCER'S NAME (S= # singles) (LP= # Albums) - "Record Title"- ARTIST-/ and OTHER PRODUCERS on the record. 20 Fingers(S = 3)- "Fat Boy"- Max-A-MillionV 'Mr. Personality"- Gillette-/ "Lick It"- Ftoula-/ Cyrus EstebanfS = 1)- "I'll Be Around"- Rappin' 4-Tay & The SpinnersVFranky J Bryan Adams(S = 1)- "Have You Ever Really Loved A Woman?"-Bryan Adams-/Robert John 'Mutt' Lange Emilto EstefanfS = 2)- "Everlasting Love'-Gloria Estefan-/ Jorge Casas Lawrence Dermer "It's Too Walter Afanasieff (S = 4)- "Always And Forever'-Luther Vandross-/ Luther Vandross "All I Want ForLate'-Gloria Estefan-/ Jorge Casas Clay Ostwald Christmas'-Mariah Carey-/ Mariah Carey "Going In Circles'-Luther Vandross-/ "Wherever Would iMeliasa Etheridge(S= 1)- "If I Wanted To/Like The Way I Do'-Melissa EtheridgeVHugh Padgham Be"-Dusty Springfield & Daryl Hall-/ Tom Sh Face To Face(S = 1)- "Disconnected"- Face To Face-/Thom Wilson Matt Aitken(S = 1)- "Total Eclipse Of The Heart"-Nicki FrenchVJohn Springate Mike Stock (|_P= 1)- "Big Choice"- Face To FaceVThom Wilson Derek Allen(S = 1)- "Let's Do It Again"- Blackgirt-/ Bruce Fairbairn(S = 2)- "Don't Tell Me What Love Can Do"- Van Halen-/ "Can't Stop -

The Ticker, October 27, 1992

,..._,...·..:-....~,~.~ ~..<I(::~;.,oi;~~~bP"'1ll$;.,rf!lt.~..:~~_ .... ..... , __ ...._ .... ' .. ". _.. ~. t , :~\~~:~~~~ ....---. _.~.....-c.--~~ _- ~ --__ ,- -.::r -•. ~: . .';'- - _- •. --- --..-~ .,-' ~ ':,.' _ '.,"" -;- ,~. .. • -," ,'-' .' ...' .. "'.':'... '.' '. , ': ... -. f:" . ,..~ ""., , •. ....,,'.. ~ '~ I-li,• ..• ~ ·.~" ~.. •"~"'.••:ra"""~' 0 Vol. 63, Number 2 Baruch College. • City University of New_.- Ypr_. October 27,1992 Former RivalsJo--.,.-. By FarahGehy Thetwohavealreadyworked knowledge him. ,. Charles Weisenhart and ,toget~,onthe USS. ,They Quaterman saidheis the,"1 e- Simon Herelle, opponents iII worked, along with ether del- gal interim chair. Iftheydon't last years Day. SessionStu- egatesto the USS, to curtail recognize me {at the Board dent presidential race, have theelectionsoftheUSSChair. meetings], they're in violation forged an alliance, and they The election, which was to be ofthe Higher Education Law, are now working' together to heldOctober11, was re-sched- Section 6204." reform the UniversityStudent uled for November 8. , The law states' that there Senate. ,. HerellerWeisenhart .and must be consecutive student · Herelle, the DSSG presi- - otherdelegatesworkedtopost- representation atBoard meet dent as well .as Baruch's del- pone the electionbecause they ings. ThejobofChairis to vote . egate to the USS, said that, feel the USS should be re- and participateatBoardmeet Weisenhartwashisfirstchoice . formed. ings. The Chair is the only to be the alternate delegate. "We should be able to imple- student vote in CUNY "If we had to get anything ment reforms before the elec- Themajorityofthe delegates done in government this year, tions," said Herelle. wantreforrns"inordertoavoid the elections had to end," said The delegates are looking to the scandals of the previous Herelle, regarding the fiercely implementspecificguidelines, years,"saidQuatennan."We're contested race for D.S.S.G. which have notyetbeenset, to trying to change the image of president last year. -

United in Victory Toledo-Winlock Soccer Team Survives Dameon Pesanti / [email protected] Opponents of Oil Trains Show Support for a Speaker Tuesday

It Must Be Tigers Bounce Back Spring; The Centralia Holds Off W.F. West 9-6 in Rivalry Finale / Sports Weeds are Here / Life $1 Midweek Edition Thursday, May 1, 2014 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com United in Victory Toledo-Winlock Soccer Team Survives Dameon Pesanti / [email protected] Opponents of oil trains show support for a speaker Tuesday. Oil Train Opponents Dominate Centralia Meeting ONE-SIDED: Residents Fear Derailments, Explosions, Traffic Delays By Dameon Pesanti [email protected] More than 150 people came to Pete Caster / [email protected] the Centralia High School audito- Toledo-Winlock United goalkeeper Elias delCampo celebrates after leaving the Winlock School District meeting where the school board voted to strike down the rium Tuesday night to voice their motion to dissolve the combination soccer team on Wednesday evening. concerns against two new oil transfer centers slated to be built in Grays Harbor. CELEBRATION: Winlock School Board The meeting was meant to be Votes 3-2 to Keep Toledo/Winlock a platform for public comments and concerns related to the two Combined Boys Soccer Program projects, but the message from attendees was clear and unified By Christopher Brewer — study as many impacts as pos- [email protected] sible, but don’t let the trains come WINLOCK — United they have played for nearly through Western Washington. two decades, and United they will remain for the Nearly every speaker ex- foreseeable future. pressed concerns about the Toledo and Winlock’s combined boys’ soccer increase in global warming, program has survived the chopping block, as the potential derailments, the unpre- Winlock School Board voted 3-2 against dissolving paredness of municipalities in the the team at a special board meeting Wednesday eve- face of explosions and the poten- ning. -

Sabotage Records

Downloaded from: justpaste.it/princeflac Sabotage Records #SAB 001-002 Driving 2 Midnight Mess #SAB 003-005 Paisley Park Extravaganza Box Set #SAB 006-007 Past, Present & Future #SAB 006b-007b Past, Present & Futu re II #SAB 008-009 (Prince's Tales From A) Spa nish Harem #SAB 010-011+040 Rock Over Germany #SAB 012-013 Sound & Vision Volume 2 #SAB 014 The Hollywood Affair #SAB 015 Emancipation Proclam ation #SAB 016-017 Sound & Vision Volume 1 #SAB 018-019 Sound & Vision Volume 3 #SAB 020-021 Atlanta, January 19th 199 7 #SAB 022-023 Aloha Hawaii #SAB 024A-B Sun, Moon & S tars #SAB 025-026 Gold Tour Finale #SAB 027-028 The Artist V's Toronto #SAB 029 Emancipation - The Secret Chapter #SAB 030-031 Late Night Shows Part 1 #SAB 032-033 Late Night Shows Part 2 #SAB 034-035 Late Night Shows Part 3 #SAB 036+039 The Inner Sanctum #SAB 037-038 Mountain View #SAB 041-042 Sound & Vision Volume 4 #SAB 043-044 Apotheosis #SAB 045-046+066 Strippe d Down #SAB 047-048 Nighttown Vega #SAB 049-050 The Freak #SAB 051-052 The War #SAB 053-054 R U Xperienced #SAB 055 Gold Aftershow 1995 #SAB 056-057 Birthday Parade #SAB 058-061 Return To Zenith #SAB 062-063 Late Night Shows Part 4 #SAB 064-065 Cafe de Paris #SAB 067-069 A Night At The Bullring #SAB 070-071 1999 Revisited #SAB 072-073 Funkspectations #SAB 074 Late Night Shows Part 5 #SAB 075-076 Rock This Joint #SAB 077-078 R U Gonna Go My Way #SAB 079-080 Studio 54 #SAB 079-080+094-095 Viva Las Vegas 1999 #SAB 081-082 Ahoy Rotterdam #SAB 083-084 Funkball #SAB 085-086 Hypno Paradise #SAB 087-088 The Spanish -

The Purple Xperience - Biography

THE PURPLE XPERIENCE - BIOGRAPHY Hailing from Minneapolis, Minnesota, The Purple Xperience has been bringing the memories of Prince and The Revolution to audiences of all generations. Led by Matt Fink (a/k/a Doctor Fink, 3x Grammy Award Winner and original member of Prince and The Revolution from 1978 to 1991), The Purple Xperience imaginatively styles the magic of Prince’s talent in an uncannily unmatched fashion through its appearance, vocal imitation and multi-instrumental capacity on guitar and piano. Backed by the best session players in the Twin Cities, Matt Fink and Marshall Charloff have undoubtedly produced the most authentic re-creation of Prince and The Revolution in the world, leaving no attendee disappointed. MATT “DOCTOR” FINK Keyboardist, record producer, and songwriter Doctor Fink won two Grammy Awards in 1985 for the motion picture soundtrack album for “Purple Rain”, in which he appeared. He received another Grammy in 1986 for the album “Parade: Music from the Motion Picture ‘Under the Cherry Moon'”, the eighth studio album by Prince and The Revolution. Matt also has two American Music Awards for “Purple Rain”, which has sold over 25 million copies worldwide since its release. Doctor Fink continued working with Prince until 1991 as an early member of the New Power Generation. He was also a member of the jazz-fusion band, Madhouse, which was produced by Prince and Eric Leeds, Prince’s saxophonist. Notable work with Prince includes co-writing credits on the songs “Dirty Mind”, “Computer Blue”, “17 Days”, “America”, and “It’s Gonna Be a Beautiful Night,” as well as performing credits on the albums “Dirty Mind”, “Controversy”, “1999”, “Purple Rain”, “Around the World in a Day”, “Parade”, “Sign ‘O’ the Times”, “The Black Album”, and “Lovesexy”.