Enugu, Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

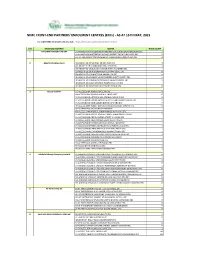

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

Parasitology August 24-26, 2015 Philadelphia, USA

Ngele K K et al., J Bacteriol Parasitol 2015, 6:4 http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2155-9597.S1.013 International Conference on Parasitology August 24-26, 2015 Philadelphia, USA Co-infections of urinary and intestinal schistosomiasis infections among primary school pupils of selected schools in Awgu L.G.A., Enugu State, Nigeria Ngele K K1 and Okoye N T2 1Federal University Ndufu Alike, Nigeria 2Akanu Ibiam Federal Polytechnic, Nigeria study on the co-infections of both urinary and intestinal schistosomiasis was carried out among selected primary schools A which include; Central Primary School Agbaogugu, Akegbi Primary School, Ogbaku Primary School, Ihe Primary School and Owelli-Court Primary School in Awgu Local Government Area, Enugu State Nigeria between November 2012 to October 2013. Sedimentation method was used in analyzing the urine samples and combi-9 test strips were used in testing for haematuria, the stool samples were parasitologically analyzed using the formal ether technique. A total of six hundred and twenty samples were collected from the pupils which include 310 urine samples and 310 stool samples. Out of the 310 urine samples examined, 139 (44.84%) were infected with urinary schistosomiasis, while out of 310 stool samples examined, 119 (38.39%) were infected with intestinal schistosomiasis. By carrying out the statistical analysis, it was found that urinary schistosomiasis is significantly higher at (p<0.05) than intestinal schistosomiasis. Children between 12-14 years were the most infected with both urinary and intestinal schistosomiasis with prevalence of 45 (14.84%) and 48 (15.48%), respectively, while children between 3-5 years were the least infected with both urinary and intestinal schistosomiasis 30 (9.68%) and 25 (8.06%), respectively. -

Mushroom Flora and Associated Insect Fauna in Nsukka Urban, Enugu State, Nigeria

Animal Research International (2008) 5(1): 801 – 803 801 MUSHROOM FLORA AND ASSOCIATED INSECT FAUNA IN NSUKKA URBAN, ENUGU STATE, NIGERIA ONYISHI, Livinus Eneje and ONYISHI, Grace Chinenye Department of Botany, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria Department of Zoology, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Enugu State, Nigeria Corresponding Author: Onyishi, L. E. Department of Botany, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria. Email: [email protected] Phone: +234 805900754 ABSTRACT The mushroom flora and associated insect pests of mushrooms in Nsukka urban was studied. The abundance of mushrooms from sampled communities is indicated with the family, Agaricaceae predominating “out of home” environment yielded more mushrooms (4.62) than the homestead environment (3.26). Insect pests associated with different mushrooms were Megasiela aganic Musca domestica Pygmaephorous stercola Paychybolus ligulatus and Drosophilla melanogester among others. Keywords: Mushroom, Pest, environment INTRODUCTION Gbolagade (2006) while highlighting some pests of Nigerian mushrooms listed such insects as Megasiela Total dependence on wild mushrooms entirely, for agaric, Megasiela boresi, Scaria fenestralis, mites food should be regarded as a means of harnessing such as Pygmaeophorus stercola, Tryophus sp and the resources associated with mushroom as a crop. the nematode Ditylenchus. These are pests even In recent times specific mushrooms are cultivated for when they are not known to cause any physical their food Mushrooms are valuable health foods low damage to the mushrooms. Through their in calories, high in vegetable proteins chitin iron zinc association, it is possible that they introduce fibre essential amino acids, vitamins, and minerals, prepagules of mushroom pathogens. Nsukka is a such as copper that help the body to produce red derived savanna (Agwu, 1997). -

Violence in Nigeria's North West

Violence in Nigeria’s North West: Rolling Back the Mayhem Africa Report N°288 | 18 May 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Community Conflicts, Criminal Gangs and Jihadists ...................................................... 5 A. Farmers and Vigilantes versus Herders and Bandits ................................................ 6 B. Criminal Violence ...................................................................................................... 9 C. Jihadist Violence ........................................................................................................ 11 III. Effects of Violence ............................................................................................................ 15 A. Humanitarian and Social Impact .............................................................................. 15 B. Economic Impact ....................................................................................................... 16 C. Impact on Overall National Security ......................................................................... 17 IV. ISWAP, the North West and -

The Igbo Traditional Food System Documented in Four States in Southern Nigeria

Chapter 12 The Igbo traditional food system documented in four states in southern Nigeria . ELIZABETH C. OKEKE, PH.D.1 . HENRIETTA N. ENE-OBONG, PH.D.1 . ANTHONIA O. UZUEGBUNAM, PH.D.2 . ALFRED OZIOKO3,4. SIMON I. UMEH5 . NNAEMEKA CHUKWUONE6 Indigenous Peoples’ food systems 251 Study Area Igboland Area States Ohiya/Ohuhu in Abia State Ubulu-Uku/Alumu in Delta State Lagos Nigeria Figure 12.1 Ezinifite/Aku in Anambra State Ede-Oballa/Ukehe IGBO TERRITORY in Enugu State Participating Communities Data from ESRI Global GIS, 2006. Walter Hitschfield Geographic Information Centre, McGill University Library. 1 Department of 3 Home Science, Bioresources Development 5 Nutrition and Dietetics, and Conservation Department of University of Nigeria, Program, UNN, Crop Science, UNN, Nsukka (UNN), Nigeria Nigeria Nigeria 4 6 2 International Centre Centre for Rural Social Science Unit, School for Ethnomedicine and Development and of General Studies, UNN, Drug Discovery, Cooperatives, UNN, Nigeria Nsukka, Nigeria Nigeria Photographic section >> XXXVI 252 Indigenous Peoples’ food systems | Igbo “Ndi mba ozo na-azu na-anwu n’aguu.” “People who depend on foreign food eventually die of hunger.” Igbo saying Abstract Introduction Traditional food systems play significant roles in maintaining the well-being and health of Indigenous Peoples. Yet, evidence Overall description of research area abounds showing that the traditional food base and knowledge of Indigenous Peoples are being eroded. This has resulted in the use of fewer species, decreased dietary diversity due wo communities were randomly to household food insecurity and consequently poor health sampled in each of four states: status. A documentation of the traditional food system of the Igbo culture area of Nigeria included food uses, nutritional Ohiya/Ohuhu in Abia State, value and contribution to nutrient intake, and was conducted Ezinifite/Aku in Anambra State, in four randomly selected states in which the Igbo reside. -

Purple Hibiscus

1 A GLOSSARY OF IGBO WORDS, NAMES AND PHRASES Taken from the text: Purple Hibiscus by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Appendix A: Catholic Terms Appendix B: Pidgin English Compiled & Translated for the NW School by: Eze Anamelechi March 2009 A Abuja: Capital of Nigeria—Federal capital territory modeled after Washington, D.C. (p. 132) “Abumonye n'uwa, onyekambu n'uwa”: “Am I who in the world, who am I in this life?”‖ (p. 276) Adamu: Arabic/Islamic name for Adam, and thus very popular among Muslim Hausas of northern Nigeria. (p. 103) Ade Coker: Ade (ah-DEH) Yoruba male name meaning "crown" or "royal one." Lagosians are known to adopt foreign names (i.e. Coker) Agbogho: short for Agboghobia meaning young lady, maiden (p. 64) Agwonatumbe: "The snake that strikes the tortoise" (i.e. despite the shell/shield)—the name of a masquerade at Aro festival (p. 86) Aja: "sand" or the ritual of "appeasing an oracle" (p. 143) Akamu: Pap made from corn; like English custard made from corn starch; a common and standard accompaniment to Nigerian breakfasts (p. 41) Akara: Bean cake/Pea fritters made from fried ground black-eyed pea paste. A staple Nigerian veggie burger (p. 148) Aku na efe: Aku is flying (p. 218) Aku: Aku are winged termites most common during the rainy season when they swarm; also means "wealth." Akwam ozu: Funeral/grief ritual or send-off ceremonies for the dead. (p. 203) Amaka (f): Short form of female name Chiamaka meaning "God is beautiful" (p. 78) Amaka ka?: "Amaka say?" or guess? (p. -

Wind Energy Evaluation for Electricity Generation Using WECS in Seven Selected Locations in Nigeria ⇑ O.S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Covenant University Repository Applied Energy 88 (2011) 3197–3206 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Applied Energy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/apenergy Wind energy evaluation for electricity generation using WECS in seven selected locations in Nigeria ⇑ O.S. Ohunakin a, , M.S. Adaramola b, O.M. Oyewola c a Mechanical Engineering Department, Covenant University, P.M.B 1023, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria b Department of Energy and Process Engineering, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway c Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria article info abstract Article history: This paper statistically examine wind characteristics from seven meteorological stations within the Received 12 November 2010 North-West (NW) geo-political region of Nigeria using 36-year (1971–2007) wind speed data measured Received in revised form 14 February 2011 at 10 m height subjected to 2-parameter Weibull analysis. It is observed that the monthly mean wind Accepted 18 March 2011 speed in this region ranges from 2.64 m/s to 9.83 m/s. The minimum monthly mean wind speed was Available online 11 April 2011 recorded in Yelwa in the month of November while the maximum value is observed in Katsina in the month of June. The annual wind speeds range from 3.61 m/s in Yelwa to 7.77 m/s in Kano. It is further Keywords: shown that Sokoto, Katsina and Kano are suitable locations for wind turbine installations with annual Mean wind speed mean wind speeds of 7.61, 7.45 and 7.77 m/s, respectively. -

South – East Zone

South – East Zone Abia State Contact Number/Enquires ‐08036725051 S/N City / Town Street Address 1 Aba Abia State Polytechnic, Aba 2 Aba Aba Main Park (Asa Road) 3 Aba Ogbor Hill (Opobo Junction) 4 Aba Iheoji Market (Ohanku, Aba) 5 Aba Osisioma By Express 6 Aba Eziama Aba North (Pz) 7 Aba 222 Clifford Road (Agm Church) 8 Aba Aba Town Hall, L.G Hqr, Aba South 9 Aba A.G.C. 39 Osusu Rd, Aba North 10 Aba A.G.C. 22 Ikonne Street, Aba North 11 Aba A.G.C. 252 Faulks Road, Aba North 12 Aba A.G.C. 84 Ohanku Road, Aba South 13 Aba A.G.C. Ukaegbu Ogbor Hill, Aba North 14 Aba A.G.C. Ozuitem, Aba South 15 Aba A.G.C. 55 Ogbonna Rd, Aba North 16 Aba Sda, 1 School Rd, Aba South 17 Aba Our Lady Of Rose Cath. Ngwa Rd, Aba South 18 Aba Abia State University Teaching Hospital – Hospital Road, Aba 19 Aba Ama Ogbonna/Osusu, Aba 20 Aba Ahia Ohuru, Aba 21 Aba Abayi Ariaria, Aba 22 Aba Seven ‐ Up Ogbor Hill, Aba 23 Aba Asa Nnetu – Spair Parts Market, Aba 24 Aba Zonal Board/Afor Une, Aba 25 Aba Obohia ‐ Our Lady Of Fatima, Aba 26 Aba Mr Bigs – Factory Road, Aba 27 Aba Ph Rd ‐ Udenwanyi, Aba 28 Aba Tony‐ Mas Becoz Fast Food‐ Umuode By Express, Aba 29 Aba Okpu Umuobo – By Aba Owerri Road, Aba 30 Aba Obikabia Junction – Ogbor Hill, Aba 31 Aba Ihemelandu – Evina, Aba 32 Aba East Street By Azikiwe – New Era Hospital, Aba 33 Aba Owerri – Aba Primary School, Aba 34 Aba Nigeria Breweries – Industrial Road, Aba 35 Aba Orie Ohabiam Market, Aba 36 Aba Jubilee By Asa Road, Aba 37 Aba St. -

The District Health System in Enugu State, Nigeria an Analysis of Policy Development and Implementation POLICY BRIEF JANUARY 2010

THE DISTRICT HEALTH SYSTEM IN ENUGU STATE, NIGERIA An analysis of policy development and implementation POLICY BRIEF JANUARY 2010 The research INTRODUCTION presented in this policy brief was The District Health System (DHS) is a form of decentralised provision of health conducted by BSC care where health facilities, health care workers, management and administrative Uzochukwu, OE structures are organised to serve a specific geographic region or population. The Onwujekwe, S Eze, N Ezuma, and NP concept of a DHS is closely linked with the primary health care movement and Uguru. is considered to be a more effective way of providing integrated health services The authors are from the Health Policy and involving communities than a centralised approach. Research Group, based at the College of Medicine, University of Nigeria, Whilst the DHS strategy aims to improve the delivery and utilisation of government Enugu-campus (UNEC); and part of the health services by eliminating parallel services, strengthening referral systems Consortium for Research on Equitable and creating structures for community accountability, country experiences Health Systems (CREHS) and funded by the Department for International suggest that implementation of this policy is particularly complex and can be Development (DFID) UK. hindered by several factors including: power struggles between State and local level actors, non-compliance or unavailability of health workers, insufficient This policy brief is based on a research report “The District Health financial resources and inadequate health system infrastructure. System in Enugu State, Nigeria: An analysis of policy development and In Enugu State, Nigeria, the DHS was introduced following the election of a new implementation” The report is available democratic government in 1999. -

BIAFRAN GHOSTS. the MASOB Ethnic Militia

Biafran Ghosts DISCUSSION PAPER 73 BIAFRAN GHOSTS The MASSOB Ethnic Militia and Nigeria’s Democratisation Process IKE OKONTA NORDISKA AFRIKAINSTITUTET, UPPSALA 2012 Indexing terms: Nigeria Biafra Democratization Political development Ethnicity Ethnic groups Interethnic relations Social movements Nationalism The opinions expressed in this volume are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. Language checking: Peter Colenbrander ISSN 1104-8417 ISBN 978-91-7106-716-6 © The author and Nordiska Afrikainstitutet 2012 Production: Byrå4 Print on demand, Lightning Source UK Ltd. Contents Acknowledgement ................................................................................................................. 5 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 1. ‘Tribesmen,’ Democrats and the Persistence of the Past ................................ 10 Explaining Democratisation in ‘Deeply-divided’ Societies ............................................ 13 ‘Tribesmen’ and Generals: ‘Shadow’ Democratisation and its Ethnic Double ............. 16 Methodology ..................................................................................................................... 20 Chapter 2. MASSOB: The Civic Origins of an Ethnic Militia ............................................... 23 Chapter 3. Reimagining Biafra, Remobilising for Secession .............................................. 33 ‘Go Down, -

Original Paper a Review of Institutional Frameworks

Urban Studies and Public Administration Vol. 3, No. 2, 2020 www.scholink.org/ojs/index.php/uspa ISSN 2576-1986 (Print) ISSN 2576-1994 (Online) Original Paper A Review of Institutional Frameworks & Financing Arrangements for Waste Management in Nigerian Cities Michael Winter1 & Fanan Ujoh1* 1 ICF Consulting, UK * Fanan Ujoh, ICF Consulting, UK Received: March 30, 2019 Accepted: March 21, 2020 Online Published: May 18, 2020 doi:10.22158/uspa.v3n2p21 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.22158/uspa.v3n2p21 Abstract Nigeria is rapidly urbanizing and is forecasted to become the 3rd most urbanized nation by 2100. Expectedly, the rapid urbanization presents challenges in many areas including the management of municipal services such as solid waste. This yawning failure is reflected in the poor quality of waste services across Nigerian cities. The study reviewed municipal waste management governance and institutional frameworks, and financing arrangements in two major cities in the North-western and south-eastern parts of Nigeria—Kano and Enugu cities. Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) using a number of structured questions checklist were conducted for the Heads of Government institutions responsible for waste management, Public Appropriation/Budget and Finance Units, as well as other key stakeholders including waste generators (residents and business owners), waste pickers and informal waste recyclers, and waste service providers. Additional, existing policy frameworks and infrastructure financing were reviewed. The findings reveal institutional and policy inadequacies, financing limitations, technical incapacity, infrastructural inadequacies, and socio-economic and attitudinal barriers, that collectively impede effective and efficient waste management service delivery in both cities. The assumption is that the findings of this study reflects the status in many Nigerian cities. -

Gusau Journal of Accounting and Finance, Vol

Gusau Journal of Accounting and Finance, Vol. 2, Issue 3, April, 2021 Gusau Journal of Accounting and Finance (GUJAF) Vol. 2 Issue 3, April, 2021 ISSN: 2756-665X A Publication of Department of Accounting and Finance, Faculty of Management and Social Sciences, Federal University Gusau, Zamfara State –Nigeria 1 Gusau Journal of Accounting and Finance, Vol. 2, Issue 3, April, 2021 BOARD COMPOSITION AND EARNINGS MANAGEMENT OF LISTED NON- FINANCIAL FIRMS IN NIGERIA Adeoye Lukmon Adewale Department of Accounting Osun State University, Osogbo [email protected] Olowookere Johnson Kolawole Department of Accounting Osun State University, Osogbo [email protected] Bankole Oluwaseun Emmanuel Department of Accounting Osun State University, Osogbo [email protected] Abstract In recent years, earnings management has gotten a lot of attention. This is owing to the fact that it is linked to the accuracy of published accounting reports. According to the academic literature, earnings management appears to be widespread among publicly traded firms. In response to calls for a higher proportion and composition of independent directors on boards and for the board of directors to be more financially sophisticated, the paper examined the effect of board composition on earnings management of listed non-financial firms in Nigeria from 2009 to 2018. Secondary data was used and extracted from various annual financial reports of the selected firms. The population for the study consisted of 117 listed non-financial firms in Nigeria as at December, 2018. This study used purposive sampling technique where 20 firms, whose data were accessible and available within the sample period of 2009 to 2018 were selected, being the most recent ten years within which the second corporate governance codes for quoted firms was introduced as a replacement to the 2003 SEC code.