Commerce & Communication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protecting the Right to Freedom of Expression Under the European Convention on Human Rights

PROTECTING THE RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION This handbook, produced by the Human Rights National Implementation Division of the Directorate General of Human Rights and Rule of Law, is a practical UNDER THE EUROPEAN CONVENTION tool for legal professionals from Council of Europe member states who wish to strengthen their skills in ON HUMAN RIGHTS applying the European Convention on Human Rights and the case law of the European Court of Human Rights in their daily work. Interested in human rights training for legal professionals? Please visit the website of the European Programme for Human Rights Education for Legal Professionals (HELP): www.coe.int/help Exergue For more information on Freedom of Expression and the ECHR, have a look at the HELP online course: 048117 Prems Citation http://www.coe.int/en/web/help/help-training-platform www.coe.int/nationalimplementation ENG The Council of Europe is the continent’s leading human Dominika Bychawska-Siniarska rights organisation. It comprises 47 member states, A handbook 28 of which are members of the European Union. All for legal practitioners www.coe.int Council of Europe member states have signed up to the European Convention on Human Rights, a treaty designed to protect human rights, democracy and the rule of law. The European Court of Human Rights oversees the implementation of the Convention in the member states. PROTECTING THE RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION UNDER THE EUROPEAN CONVENTION ON HUMAN RIGHTS A handbook for legal practitioners Dominika Bychawska-Siniarska Council of Europe The opinions expressed in this work are the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. -

Slogans, Brands and Purchase Behaviour of Students

Published in Young Consumers by Emerald. The original publication is available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-07-2019-1020. This article is deposited under the Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial International Licence 4.0 (CC BY-NC 4.0). Any reuse is allowed in accordance with the terms outlined by the licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). To reuse the AAM for commercial purposes, permission should be sought by contacting [email protected]. Slogans, Brands and Purchase Behaviour of Students Maria Rybaczewska, University of Stirling, Stirling, Scotland, University of Social Sciences, Lodz, Poland, Siriphat Jirapathomsakul, Cosmo Group Public Company Limited, Bangkok, Thailand Yiduo Liu, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Hubei Province Branch, Hubei, China Wai Tsing Chow, University of Stirling, Stirling, Scotland Mai Thanh Nguyen, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam, Leigh Sparks, University of Stirling, Stirling, Scotland, Stirling Management School Marketing and Retail Divsion FK9 4NT Stirling, Scotland, United Kingdom Abstract Purpose: The aim of this paper is to extend the understanding of the influence of slogans (e.g. “Dare for More”) on brand awareness and purchase behaviour of students. Design/methodology/approach: Data were collected thorough 34 in-depth face-to-face interviews with university students, using the Customer Decision Process (CDP) model as an approach. Findings: Our research confirmed that conciseness, rhythm and jingle are key features strengthening customers’ recall and recognition, both being moderators of slogans’ power. The role and influence of slogans depend on the stage of the customer decision making process. Key influencers remain product quality, popularity and price, but appropriate and memorable slogans enhance products’ differentiation and sale. -

The Influence of Brand Effect on Slogan's Memorability

European Research Studies Journal Volume XXII, Issue 4, 2019 pp. 88-100 The Influence of Brand Effect on Slogan‘s Memorability Submitted 23/05/19, 1st revision 28/06/19, 2nd revision 17/08/19, accepted 20/10/19 Paulo Duarte Silveira1, Paulo Bogas2 Abstract: Purpose: The main aim of this article is to examine the influence of consumers’ brand effect on their ability to remember brand slogans. Design/Methodology/Approach: An empirical quantitative study was carried out via an online questionnaire, analyzing 370 real costumers of three telecom B2C service providers in Portugal. Findings: The results tend to indicate to not corroborate the positive influence of brand effect on brand slogan memorability. However, it was also found evidence to raise doubts on the absence of the relationships, since some components of brand effect had a positive impact on slogan recognition in some of the brands studied. Practical implications: Brands might consider focusing on other dimensions besides brand effect, if their aim is to increase brand and slogan awareness. However, since some contradictory results were verified, managers should not view that implication as a golden rule for management and branding decisions. Originality/Value: The main contribution of this study is to shed a light on a relation not yet sufficiently explored in previous studies related to slogan’s effectiveness. Keywords: Slogan, brand love, brand effect, brand recall, brand recognition. JEL Codes: M31,M37. Paper type: Research article. Acknowledgements: Authors acknowledge the support from the affiliation institutions Polytechnic Institute of Setúbal and CEFAGE-UE. CEFAGE-UE has financial support from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (Grant UID/ECO/04007/2013) and FEDER/COMPETE (POCI-01- 0145-FEDER-007659). -

The Importance of Advertising Slogans and Their Proper Designing in Brand Equity

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INDUSTRIAL ORGANIZATIONAL LEADERSHIP MANAGEMENT 2013, VOL. 2; NO. 2; 62-69 INSTITUTE THE IMPORTANCE OF ADVERTISING SLOGANS AND THEIR PROPER DESIGNING IN BRAND EQUITY Somayeh Abdia*, Abdollah Irandoustb a. Islamic Azad University, Ardabil branch, Ardabil, Iran b. Entrepreneurship management, University of Allameh Tabatabaii, Tehran, Iran Abstract The term slogan derives from Slough-ghairm, pronounced as Slogorm from Scottish Gaelic which means battle cry. Slogan is usually an unforgettable phrase that is frequently used to express an idea or purpose. Slogans have been employed in religious and political areas since long time ago, but today they are mostly used in business and trading. They vary from other ordinary text and images, and often because of their simple structure cannot convey a lot of concepts and details. Hereupon, slogans instead of drawing specific audience, address general audience to convey their particular meanings. Brand owners pay lots of money to advertising agencies to come up with snappy advertising slogans. Advertising slogans often claim to have knowledge of something and attempt to show it. Slogans usually serve a substantial role in calling audience’s attention to one or more aspects of a product or service. Normally slogans claim that the advertised product or service is of the highest quality, or is the most delicious, the most inexpensive, or nutritious… one. The slogans should point out, at least, the most important advantage of a product, or respond to the audience’s needs, or offer more benefits for their future/probable customers. Keywords: advertising slogans, brand equity, competitive markets, customer knowledge 62 Introduction Advertising slogans and promotional tools enable companies to introduce themselves, their products, or services. -

Slogan Word Count and the Effects on Consumer Behavior

SLOGAN WORD COUNT AND THE EFFECTS ON CONSUMER BEHAVIOR Paige Scro Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2017 APPROVED: Tammy Kinley, Major Professor Sanjukta Pookulangara, Committee Member Lynn Brandon. Committee Member Bugao Xu, Chair of the Department of Merchandising and Digital Retailing Judith C. Forney, Dean of the College of Merchandising, Hospitality and Tourism Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Scro, Paige. Slogan Word Count and the Effects on Consumer Behavior. Master of Science (Merchandising), December 2017, 90 pp., 22 tables, 2 figures, references, 83 titles. Slogans can be attributed as a way in which to communicate a brand's message to its key consumer. An effectively established brand amongst targeted consumers can in turn generate profitability and ever further promote the brand. The purpose of this paper was to investigate the effectiveness of advertisements that employ vague or precise cosmetic product brand slogans among both male and female consumers. Ultimately, the end goal of marketing is to make a sale. Additionally, the purpose of this study was to determine whether or not the length of a slogan is an influential factor on the participant's motivation to purchase a cosmetic or skincare product. Data was collected through the use of survey in an online social media format, in order to test the effectiveness of different lengths of slogans for slogan recall, brand recall, brand awareness and purchase intention. Prior research and hypotheses were used to predict the concept that shorter more concise or precise slogans in this study would heighten the levels of all measured variables in the study, slogan recall, brand recall, brand awareness and purchase intention. -

The Effect of Advertising Credibility: Could It Change Consumers' Attitude

The effect of advertising credibility: could it change consumers’ attitude and purchase intentions? A research about different advertising formats on the relationship between advertising credibility and consumers’ attitude and purchase intentions. Romy Verstraten 356757 Master thesis Economics & Business Erasmus School of Economics Erasmus University Rotterdam August 2015 Master Thesis – MSc Economics and Business Master specialization: Marketing The effect of advertising credibility: could it change consumers’ attitude and purchase intentions? Romy Verstraten (356757) Department of Erasmus School of Economics Erasmus University Rotterdam Supervisor: Dr. Zhiying Jiang August 2015 Abstract The aim of this research is to investigate whether brand versus experience oriented advertising has an influence on the relationship between advertising credibility and consumers’ attitude and purchase intentions. Hereby, it examines what kind of effect different advertising formats have on consumers’ perception about advertising. Based on a sample of 100 respondents, acquired from an online survey, this study finds that consumers trust a brand more, believe a brand is more authentic and are able to affirm themselves with a brand more easily when they are exposed to brand oriented ads. Moreover, it is shown that when the semantic memory of consumers is being triggered within ads the brand image consumers have about a brand is stimulated. This indicates that brand oriented advertisements are more effective in creating the perception of a trustworthy, authentic and affirmable brand. Regressions on the multiple relationships between the credibility drivers trust, authenticity, affirmation and consumers’ attitude and purchase intentions show that the only significant proven relationship is the one between attitude towards brands and purchase intentions. -

Creative Use of Internet Memes in Advertising

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 57 (2016) 33-41 EISSN 2392-2192 Creative Use of Internet Memes in Advertising Beata Bury Philological School of Higher Education, Sienkiewicza Street 32, 50-335 Wroclaw, Poland E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT This study focuses on the creativity of Internet memes used in advertising campaigns. A random selection of memes is analysed. It is argued that the creation of Internet memes involves amusing juxtaposition of phrases and pictures. Advertisers have taken advantage of this Internet phenomenon. They use familiar ideas and background knowledge in order to make new and surprising combinations of Internet memes. Advertisers’ aim is to play creatively with memetic elements. To conclude, being able to skilfully and cleverly alter the original meme and create the humourous effect are the main goals of marketers. Keywords: creativity; Internet memes; advertising; LOLcats; Doge memes 1. INTRODUCTION The Internet has altered the way people live and become an important part of their life. The era of Web 2.0 has given netizens many ways of communicating, for instance via blogs, forums or chats. The Internet allows people to share their ideas, beliefs and thoughts. In recent years, the Internet memes have received considerable attention in popular culture and advertising. Every netizen has been exposed, to a greater or lesser degree, to this Internet phenomenon. A picture of a baby with an amusing tag attached or a video of cute animals that spread through Facebook or Twitter are all examples of Internet memes. Internet memes are thought to be a new Internet-era communication. -

The Influence of Customer Retention Time on Slogan Recall and Recognition: an Empirical Study

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OAR@UM International Journal of Economics and Business Administration Volume VI, Issue 1, 2018 pp. 3-13 The Influence of Customer Retention Time on Slogan Recall and Recognition: An Empirical Study Paulo Duarte Silveira1*, Susana Galvão2, Paulo Bogas3 Abstract: This research intends to explore some of the roots that might influence the effectiveness of slogans. The specific aim of the study is to examine the relationship between the customer retention time and the recall and recognition of brand slogans. This is as an important issue to be studied on branding, because no previous studies were found, and the better understanding of such relationship will help on deciding which marketing mix elements should be managed in order for the brands to obtain a more memorable and stable position in the consumers’ mind. An empirical quantitative study was conducted with an online survey research method employed to collect data from 370-real consumers of three B2C brands in telecom industry. The results revealed that customer seniority (retention time) did not significantly influence slogan recall nor recognition. Keywords: Slogans; Branding; Positioning; Advertising. JEL Classification: M31, M37. 1 College of Business Administration-Polytechnic Institute of Setúbal, Setúbal, Portugal, and CEFAGE-UE, Évora, Portugal. Corresponding author email: [email protected] 2 College of Business Administration-Polytechnic Institute of Setúbal, Setúbal, Portugal. 3 College of Business Administration-Polytechnic Institute of Setúbal, Setúbal, Portugal. * Authors are grateful to the anonymous participants in the study and their responses to the survey. -

From Organization to Coordination, the Change in the Public José María Perceval Ph

11 Comunicación número 32 enero - junio 2015 | pp. 11-22 From Organization to Coordination, the Change in the Public José María Perceval Ph. D. Professor Spaces of Communication [email protected] in the Arab World Núria Simelio Ph. D. Associate Professor and its Connection [email protected] Santiago Tejedor to the Social Networks Ph. D. Associate Professor [email protected] in the 2011 Movements Department of Journalism and Communication Studies Resumen Autonomous University En este artículo se analiza el cambio de los espacios públicos de comunicación of Barcelona (UAB) en el mundo árabe y su conexión con las redes sociales durante los Código ORCID: acontecimientos revolucionarios recientes, especialmente, en Túnez y 0000-0002-5539-9800 Egipto. El desprestigio del poder estuvo ligado al desprestigio de los medios tradicionales de comunicación de masas que siguieron los mecanismos habituales de desinformación y descrédito. En contraste, los participantes en las revueltas respondieron con innovadoras y modernas estrategias narrativas de contra-desinformación y explicación. A los canales satelitales y los blogs de internet que prepararon la opinión pública, se añadieron las redes sociales que organizaron las acciones concretas potenciadas por twitter y la expansión del teléfono móvil. La apropiación de los nuevos soportes por parte de los jóvenes, dándoles una conciencia de grupo para galvanizar el sentimiento colectivo de frustración y su utilización como elemento de conexión inmediata entre miles de activistas, hizo triunfar un movimiento gracias a la inmediatez, la sorpresa y el encadenamiento rápido de acciones. Abstract Palabras clave In this article we shall analyse the change in the public spaces of Espacio público, Revolución communication in the Arab world and its connection with the social networks árabe, Egipto, Túnez, Redes during the recent revolutionary events in Tunisia and Egypt. -

The World's Collections of Historical Advertisements and Marketing

Archiving the Archiving the Archives: The World’s Archives: The World’s Collections Collections of Historical Advertisements of Historical Advertisements and and Marketing Ephemera Marketing Ephemera 32 Fred K. Beard Gaylord College, University of Oklahoma, USA Abstract Purpose – When advertising historians began searching for substantial collections and archives of historical advertisements and marketing ephemera in the 1970s, some reported such holdings were rare. This paper reports the findings of the first systematic attempt to assess the scope and research value of the world’s archives and collections devoted to advertising and marketing ephemera. Approach – Searches of the holdings of museums, libraries, and the Internet led to the identification and description of 175 archives and collections of historical significance for historians of marketing and advertising, as well as researchers interested in many other topics and disciplines. Limitations – The search continued until a point of redundancy was reached and no new archives or collections meeting the search criteria emerged. There remains the likelihood, however, that other archives and collections exist, especially in non-Western countries. Contribution – The lists of archives and collections resulting from the research reported in this paper represent the most complete collection of such sources available. Identified are the world’s oldest and largest collections of advertising and ephemera. Also identified are quite extraordinary collections of historically unique records and artifacts. The findings make valuable contributions to the work of historians and other scholars by encouraging more global and cross-cultural research and historical analyses of trends and themes in professional practices in marketing and advertising and their consequences over a longer period than previously studied. -

The Campaign Slogans of 2008 and 2016: Meta-Analysis Of

The campaign slogans of 2008 and 2016 : meta-analysis of the literature produced on political slogans with a view to establishing a protocol for analyzing the structure and rhetoric of Barack Obama’s, John McCain’s, Donald Trump’s and Hillary Clinton’s slogans Louise Anglès d’Auriac To cite this version: Louise Anglès d’Auriac. The campaign slogans of 2008 and 2016 : meta-analysis of the literature pro- duced on political slogans with a view to establishing a protocol for analyzing the structure and rhetoric of Barack Obama’s, John McCain’s, Donald Trump’s and Hillary Clinton’s slogans. Humanities and Social Sciences. 2018. dumas-01960550 HAL Id: dumas-01960550 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01960550 Submitted on 19 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Louise-Noor Anglès d’Auriac École Normale Supérieure de Lyon Département des Langues, littératures et civilisations étrangères Parcours « Études Anglophones » The campaign slogans of 2008 and 2016 Meta-analysis of the literature produced on political slogans with a view to establishing a protocol for analyzing the structure and rhetoric of Barack Obama’s, John McCain’s, Donald Trump’s and Hillary Clinton’s slogans. -

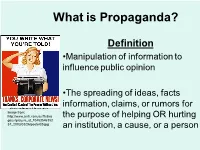

What Is Propaganda?

What is Propaganda? Definition •Manipulation of information to influence public opinion •The spreading of ideas, facts information, claims, or rumors for Image from: http://www.smh.com.au/ffxIma the purpose of helping OR hurting ge/urlpicture_id_10483546352 57_2003/03/26/poster05.jpg an institution, a cause, or a person Characteristics of Propaganda • Propaganda’s persuasive techniques are regularly applied by politicians, advertisers, journalists, radio personalities, and others who are interested in influencing human behavior • Propagandistic messages can be used to accomplish positive social ends, as in campaigns to reduce drunk driving, but they are also Image from:http://www.cynical used to win elections and to sell c.com/archives/bloggra products phics/Russian.jpg Propaganda • Persuading with BRIEF techniques not massive amounts of facts (flyers, pins, ads, slogans, etc.) • Can manipulate people or distort information • Often appeals to emotions Examples of Propaganda • During World War II, propaganda was used by nations (Russia & the United States) on both sides to shape public opinion and build loyalty • The Nazis used propaganda to promote Nazism, anti-Semitism, and the belief of an Aryan master race • Nazi propaganda was delivered Image from: http://www.wwii- collectibles.com/grp203.jpg through the Nazi-controlled mass media, banners, posters, and in fanatical/passionate speeches to audiences at mass rallies What are Slogans? Definition • A motto; a saying • A phrase expressing the aims or nature of an enterprise, organization,