Preserving, Planning, and Promoting the Lower East Side

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of NYC”: The

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa B.A. in Italian and French Studies, May 2003, University of Delaware M.A. in Geography, May 2006, Louisiana State University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2014 Dissertation directed by Suleiman Osman Associate Professor of American Studies The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of the George Washington University certifies that Elizabeth Healy Matassa has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 21, 2013. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 Elizabeth Healy Matassa Dissertation Research Committee: Suleiman Osman, Associate Professor of American Studies, Dissertation Director Elaine Peña, Associate Professor of American Studies, Committee Member Elizabeth Chacko, Associate Professor of Geography and International Affairs, Committee Member ii ©Copyright 2013 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa All rights reserved iii Dedication The author wishes to dedicate this dissertation to the five boroughs. From Woodlawn to the Rockaways: this one’s for you. iv Abstract of Dissertation “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 This dissertation argues that New York City’s 1970s fiscal crisis was not only an economic crisis, but was also a spatial and embodied one. -

New York City Council Environmental SCORECARD 2017

New York City Council Environmental SCORECARD 2017 NEW YORK LEAGUE OF CONSERVATION VOTERS nylcv.org/nycscorecard INTRODUCTION Each year, the New York League of Conservation Voters improve energy efficiency, and to better prepare the lays out a policy agenda for New York City, with goals city for severe weather. we expect the Mayor and NYC Council to accomplish over the course of the proceeding year. Our primary Last month, Corey Johnson was selected by his tool for holding council members accountable for colleagues as her successor. Over the years he has progress on these goals year after year is our annual been an effective advocate in the fight against climate New York City Council Environmental Scorecard. change and in protecting the health of our most vulnerable. In particular, we appreciate his efforts In consultation with over forty respected as the lead sponsor on legislation to require the environmental, public health, transportation, parks, Department of Mental Health and Hygiene to conduct and environmental justice organizations, we released an annual community air quality survey, an important a list of eleven bills that would be scored in early tool in identifying the sources of air pollution -- such December. A handful of our selections reward council as building emissions or truck traffic -- particularly members for positive votes on the most significant in environmental justice communities. Based on this environmental legislation of the previous year. record and after he earned a perfect 100 on our City The remainder of the scored bills require council Council Scorecard in each year of his first term, NYLCV members to take a public position on a number of our was proud to endorse him for re-election last year. -

God in Chinatown

RELIGION, RACE, AND ETHNICITY God in Chinatown General Editor: Peter J. Paris Religion and Survival in New York's Public Religion and Urban Transformation: Faith in the City Evolving Immigrant Community Edited by Lowell W. Livezey Down by the Riverside: Readings in African American Religion Edited by Larry G. Murphy New York Glory: Kenneth ]. Guest Religions in the City Edited by Tony Carnes and Anna Karpathakis Religion and the Creation of Race and Ethnicity: An Introduction Edited by Craig R. Prentiss God in Chinatown: Religion and Survival in New York's Evolving Immigrant Community Kenneth J. Guest 111 New York University Press NEW YORK AND LONDON NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS For Thomas Luke New York and London www.nyupress.org © 2003 by New York University All rights reserved All photographs in the book, including the cover photos, have been taken by the author. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Guest, Kenneth J. God in Chinatown : religion and survival in New York's evolving immigrant community I Kenneth J. Guest. p. em.- (Religion, race, and ethnicity) Includes bibliographical references (p. 209) and index. ISBN 0-8147-3153-8 (cloth) - ISBN 0-8147-3154-6 (paper) 1. Immigrants-Religious life-New York (State)-New York. 2. Chinese Americans-New York (State )-New York-Religious life. 3. Chinatown (New York, N.Y.) I. Title. II. Series. BL2527.N7G84 2003 200'.89'95107471-dc21 2003000761 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Chinatown and the Fuzhounese 37 36 Chinatown and the Fuzhounese have been quite successful, it also includes many individuals who are ex tremely desperate financially and emotionally. -

The Decline of New York City Nightlife Culture Since the Late 1980S

1 Clubbed to Death: The Decline of New York City Nightlife Culture Since the Late 1980s Senior Thesis by Whitney Wei Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of BA Economic and Social History Barnard College of Columbia University New York, New York 2015 2 ii. Contents iii. Acknowledgement iv. Abstract v. List of Tables vi. List of Figures I. Introduction……………………………………………………………………7 II. The Limelight…………………………………………………………………12 III. After Dark…………………………………………………………………….21 a. AIDS Epidemic Strikes Clubland……………………..13 b. Gentrification: Early and Late………………………….27 c. The Impact of Gentrification to Industry Livelihood…32 IV. Clubbed to Death …………………………………………………………….35 a. 1989 Zoning Changes to Entertainment Venues…………………………36 b. Scandal, Vilification, and Disorder……………………………………….45 c. Rudy Giuliani and Criminalization of Nightlife………………………….53 V. Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………60 VI. Bibliography………………………………………………………………..…61 3 Acknowledgement I would like to take this opportunity to thank Professor Alan Dye for his wise guidance during this thesis process. Having such a supportive advisor has proven indispensable to the quality of this work. A special thank you to Ian Sinclair of NYC Planning for providing key zoning documents and patient explanations. Finally, I would like to thank the support and contributions of my peers in the Economic and Social History Senior Thesis class. 4 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to investigate the impact of city policy changes and the processes of gentrification on 1980s nightlife subculture in New York City. What are important to this work are the contributions and influence of nightlife subculture to greater New York City history through fashion, music, and art. I intend to prove that, in combination with the city’s gradual revanchism of neighborhood properties, the self-destructive nature of this after-hours sector has led to its own demise. -

Women Work It at W.T.C

downtownCOLLABORATIVE ART SHOWS, P. 23 ® express VOLUME 22, NUMBER 11 THE NEWSPAPER OF LOWER MANHATTAN JULY 24 - 30, 2009 25 Broadway makes the grade for private school’s expansion BY JULIE SHAPIRO “You walk right out our Claremont Prep’s $30 door, cross Bowling Green, million expansion is back on and there you are,” Koffl er track after the school fi nal- said. “It’s a wonderful build- ized a lease this week for ing, it’s close by, and the 200,000 square feet at 25 staff is really thrilled.” Broadway. Claremont was able to Claremont will use the back out of the 100 Church space for middle and high St. lease because owner The school classes starting in the Sapir Organization took a fall of 2010, said Michael long time to get their bank Koffl er, C.E.O. of Met Schools, to sign off on the deal, Claremont’s parent company. Koffl er said. Koffl er made a similar The asking rent at 25 announcement in March, Broadway was $39 per square saying the school had leased foot, compared to $40 at space for its expansion at 100 100 Church. Koffl er said he Church St., but Claremont paid very close to the asking opted out of that deal rent at 25 Broadway, which because the 25 Broadway is owned by the Wolfson space was better, Koffl er Group. Wolfson and Sapir said. A major tipping point could not immediately be was 25 Broadway’s location, reached for comment. just steps from Claremont’s Claremont had detailed Broad St. -

Calm Down NEW YORK — East Met West at Tiffany on Sunday Morning in a Smart, Chic Collection by Behnaz Sarafpour

WINSTON MINES GROWTH/10 GUCCI’S GIANNINI TALKS TEAM/22 WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’MONDAY Daily Newspaper • September 13, 2004 • $2.00 Accessories/Innerwear/Legwear Calm Down NEW YORK — East met West at Tiffany on Sunday morning in a smart, chic collection by Behnaz Sarafpour. And in the midst of the cross-cultural current inspired by the designer’s recent trip to Japan, she gave ample play to the new calm percolating through fashion, one likely to gain momentum as the season progresses. Here, Sarafpour’s sleek dress secured with an obi sash. For more on the season, see pages 12 to 18. Hip-Hop’s Rising Heat: As Firms Chase Deals, Is Rocawear in Play? By Lauren DeCarlo NEW YORK — The bling-bling world of hip- hop is clearly more than a flash in the pan, with more conglomerates than ever eager to get a piece of it. The latest brand J.Lo Plans Show for Sweetface, Sells $15,000 Of Fragrance at Macy’s Appearance. Page 2. said to be entertaining suitors is none other than one that helped pioneer the sector: Rocawear. Sources said Rocawear may be ready to consider offers for a sale of the company, which is said to generate more than $125 million in wholesale volume. See Rocawear, Page4 PHOTO BY GEORGE CHINSEE PHOTO BY 2 WWD, MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 2004 WWW.WWD.COM WWDMONDAY J.Lo Talks Scents, Shows at Macy’s Accessories/Innerwear/Legwear By Julie Naughton and Pete Born FASHION The spring collections kicked into high gear over the weekend with shows Jennifer Lopez in Jennifer Lopez in from Behnaz Sarafpour, DKNY, Baby Phat and Zac Posen. -

A Map of Free Meals in Manhattan

washington heights / inwood north of 155 st breakfast lunch dinner ARC XVI Fort Washington m–f 12–1 pm 1 4111 BROADWAY Senior Center $2 ENTER 174th ST (A 175 ST) 2 ARC XVI Inwood Senior Center m–f 8:30– m–f 12–1 p m 84 VERMILYEA AVE (A DYCKMAN ST) 9:30 am $1 $1.50 Church on the Hill Older Adults 3 Luncheon Club 2005 AMSTERDAM AVE m–f 1 p m A map of free meals in Manhattan (C 163 ST AMSTERDAM AVE) $1.50 W 215 ST m–f 9– m–f 12–1:30 washington 4 Dyckman Senior Center heights & 3754 TENTH AVE (1 DYCKMAN ST) 10:30 am 50¢ pm $1 BROADWAY inwood Harry & Jeanette Weinberg m–f, su map key symbols key 5 Senior Center 54 NAGLE AVE 12–1 pm (1 DYCKMAN ST) $1.50 2 TENTH AVE SEAMEN AVE Moriah Older Adult Luncheon m-th 1:15–2 pm All welcome Mobile kitchen Residents only 204 ST 11 — 207 ST 6 f 11:45–12:15 pm Club 90 BENNETT AVE (A 181 ST) $1.50 — 205 ST Brown bag meal Only HIV positive 4 Riverstone Senior Center m–f 12–1 Senior Citizens — 203 ST 7 99 FORT WASHINGTON AVE (1 ,A,C 168 ST) pm $1.50 VERMILYEA SHERMANAVE AVE AVE POST AVE — 201 ST m–f m–f 12–1 pm Must attend Women only 8 STAR Senior Center 650 W 187th ST (1 191 ST) 9 a m $1.50 Under 21 services ELLWOOD ST NINTH NAGLE AVE UBA Mary McLeod Bethune Senior m–f 9 am m–f 12–1 pm 9 Center 1970 AMSTERDAM AVE ( 1 157 ST) 50¢ $1 HIV Positive Kosher meals 5 Bethel Holy Church 10 tu 1–2 pm 12 PM 922 SAINT NICHOLAS AVE (C 155 ST) Women Must call ahead to register The Love Kitchen m–f 4:30– BROADWAY 11 3816 NINTH AVE (1 207 ST) 6:30 pm W 191 ST Residents AVE BENNETT North Presbyterian Church sa 12–2 pm 8 W 189 ST 12 525 W 155th ST (1 157 ST) 6 W 187 ST W 186 ST W 185 ST east harlem W 184 ST 110 st & north, fifth ave–east river breakfast lunch dinner harlem / morningside heights ST AVE NICHOLAS W 183 ST 110 155 Corsi Senior Center m–f 12– st– st; fifth ave–hudson river breakfast lunch dinner 63 W 181 ST 307 E 116th ST ( 6 116 ST) 1 pm $1.50 WADSWORTH AVE WADSWORTH 13 Canaan Senior Service Center m–f W 180 ST W 179 ST James Weldon Johnson Senior m–f 12– 10 LENOX AVE (2 ,3 CENTRAL PARK NO. -

Sounds of the Great Religions

The Voice of the West Village WestView News VOLUME 14, NUMBER 6 JUNE 2018 $1.00 Sounds of the Great Religions By George Capsis ate—"Papadopoulos" which means “son of the father, or more accurately, son of the The dramatic, almost theatrical interior priest, for as you know, Greek priests can space of St. Veronica invites imaginative and do marry). uses and we came up with The Sounds A very young looking Panteleimon came of the Great Religions, a survey of great down for lunch in the garden and shortly it musical moments from the world’s great was like talking to a relative. That is what religions. is great about being Greek—it is really one Having been exposed to the Greek Or- big family. thodox church (my father was Greek, my I casually mentioned how long I thought mother a Lutheran German), I knew how the presentation should be and he snapped dramatic it could be so I called Archdea- "no, no, that's too long. Yah gotta make it con Panteleimon Papadopoulos who is in shorter.” charge of music at the Archdiocese. We were hours away from sending to the Archdeacon Panteleimon Papadopoulos A HUNDRED VOICES ECHO A THOUSAND YEARS: The Musical Director of the Greek Orthodox printer when I asked if he could send some (yes I know Greek names are a bit much Church offered its choir to celebrate the great moments in Orthodox history for the Sounds of thoughts about the presentation and here but in this case the last name is appropri- the Great Religions program at St. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

View from the Street Neighborhood Overview: Manhattan

EASTERN CONSOLIDATED VIEW FROM THE STREET NEIGHBORHOOD OVERVIEW: MANHATTAN APRIL 2017 EASTERN CONSOLIDATED www.easternconsolidated.com VIEW FROM THE STREET NEIGHBORHOOD OVERVIEW: MANHATTAN OVERVIEW Dear Friends: Of the international investors, Chinese While asking rents for retail space on firms increased their acquisitions of major Manhattan corridors such as Fifth We are pleased to introduce the Manhattan properties to $6.5 billion in Avenue, Madison Avenue, East 57th inaugural issue of View from the Street, 2016, up from $4.7 billion in 2015. The Street, West 34th Street, and Times Eastern Consolidated’s research report most significant transactions included Square can reach up to $4,500 per on neighborhoods in core Manhattan, China Life’s investment in 1285 Avenue square foot, our analysis shows that which will provide you with a snapshot of the Americas, which traded for there are dozens of blocks in prime of recent investment property sales, $1.65 billion in May 2016, and China neighborhoods where entrepreneurial average residential rents, and average Investment Corporation’s investment in retailers can and do rent retail space for retail rents. 1221 Avenue of the Americas, in which under $200 per square foot. partial interest traded for $1.03 billion in As is historically the case in Manhattan, December 2016. Our review of residential rents shows neighborhoods with significant office that asking rents for two-bedroom buildings such as Midtown West, Investor interest in cash-flowing multifamily apartments are ranging from a low of Midtown East, and Nomad/Flatiron properties remained steady throughout $3,727 on the Lower East Side up to recorded the highest dollar volume 2016, with nearly 60 percent of these $9,370 in Tribeca. -

Stores of Memory:” an Oral History of Multigenerational Jewish Family Businesses in the Lower East Side

“Stores of Memory:” An Oral History of Multigenerational Jewish Family Businesses in the Lower East Side By Liza Zapol Advisor: Dr. Ruksana Sussewell Department of Sociology An Audio Thesis and Annotation submitted to the Faculty of Columbia University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Oral History April 28, 2011 1 I have walked through many lives, some of them my own, and I am not who I was, though some principle of being abides, from which I struggle not to stray. -Stanley Kunitz, 1979 © Copyright by Liza Zapol 2011 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements..............................................................................................................3 “Stores of Memory” with Annotation..............................................................................4 History and Memory of the Jewish Lower East Side..........................................................4 Visiting Lower East Side Stores........................................................................................11 Streit’s Matzo Factory........................................................................................................14 Harris Levy Linens............................................................................................................21 A Candy Story Interlude....................................................................................................27 Economy Candy.................................................................................................................27 -

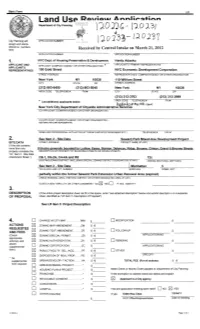

Zoning Text Amendment (ZR Sections 74-743 and 74-744) 3

UDAAP PROJECT SUMMARY Site BLOCK LOT ADDRESS Site 1 409 56 236 Broome Street Site 2 352 1 80 Essex Street Site 2 352 28 85 Norfolk Street Site 3 346 40 (p/o) 135-147 Delancey Street Site 4 346 40 (p/o) 153-163 Delancey Street Site 5 346 40 (p/o) 394-406 Grand Street Site 6 347 71 178 Broome Street Site 8 354 1 140 Essex Street Site 9 353 44 116 Delancey Street Site 10 354 12 121 Stanton Street 1. Land Use: Publicly-accessible open space, roads, and community facilities. Residential uses - Sites 1 – 10: up to 1,069,867 zoning floor area (zfa) - 900 units; LSGD (Sites 1 – 6) - 800 units. 50% market rate units. 50% affordable units: 10% middle income (approximately 131-165% AMI), 10% moderate income (approximately 60-130% AMI), 20% low income, 10% senior housing. Sufficient residential square footage will be set aside and reserved for residential use in order to develop 900 units. Commercial development: up to 755,468 zfa. If a fee ownership or leasehold interest in a portion of Site 2 (Block 352, Lots 1 and 28) is reacquired by the City for the purpose of the Essex Street Market, the use of said interest pursuant to a second disposition of that portion of Site 2 will be restricted solely to market uses and ancillary uses such as eating establishments. The disposition of Site 9 (Block 353, Lot 44) will be subject to the express covenant and condition that, until a new facility for the Essex Street Market has been developed and is available for use as a market, Site 9 will continue to be restricted to market uses.