Introduction PAINTING by CANDLELIGHT in MAO’S CHINA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Daily 0803 D6.Indd

life CHINA DAILY CHINADAILY.COM.CN/LIFE FRIDAY, AUGUST 3, 2012 | PAGE 18 Li Keran bucks market trend The artist has become a favorite at auction and his works are fetching record prices. But overall, the Chinese contemporary art market has cooled, Lin Qi reports in Beijing. i Keran (1907-89) took center and how representative the work is, in addi- stage at the spring sales with tion to the art publications and catalogues it two historic works both cross- has appeared in.” ing the 100 million yuan ($16 Though a record was set by Wan Shan million) threshold. Hong Bian, two other important paintings by His 1974 painting of former Li were unsold, which came as no surprise for Lchairman Mao Zedong’s residence in Sha- art collectors like Yan An. oshan, the revolutionary holy land in Hunan “Both big players and new buyers are bid- province, fetched 124 million yuan at China ding for the best works of the blue-chip art- Guardian, in May. ists, while the market can’t provide as many Th ree weeks later his large-scale blockbust- top-notch artworks and provide the reduced er of 1964, Wan Shan Hong Bian (Th ousands risks that people expect. of Hills in a Crimsoned View), was sold for a “Th is is because in the face of an unclear personal record of 293 million yuan at Poly market, cautious owners would rather keep International Auction. those items, which achieved skyscraping Li, a prominent figure in 20th-century prices, rather than fl ip them at auction,” Yan Chinese art, is recognized for innovating the says. -

Marketing Strategy Analysis of the Palace Museum

Journal of Finance Research | Volume 03 | Issue 02 | October 2019 Journal of Finance Research https://ojs.s-p.sg/index.php/jfr ARTICLE Marketing Strategy Analysis of the Palace Museum Qi Wang1* Huan Liu1 Kaiyi Liu2 1. School of management, Shandong University of Technology, Zibo, Shandong, 255000, China 2. Shandong University of Science and Technology, Qingdao, Shandong, 266000, China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history The development of cultural innovation is benecial for museums to give Received: 8 August 2019 full play to their cultural advantages and improve their economic benets, accordingly forming a virtuous circle. This paper analyzes the cultural Revised: 13 August 2019 and creative brand marketing environment and strategy of the Palace Mu- Accepted: 24 October 2019 seum, hoping to provide some references for other museums through the Published Online: 31 October 2019 analysis and summary of cultural and creative brand marketing strategy of the Palace Museum. Keywords: The Palace Museum Cultural and creative industries SWOT analysis Non-prot organizations 1. Overview of the Palace Museum vantages, seize the opportunity of cultural and creative de- velopment, actively explore ways of cultural and creative ith the continuous development of the econo- innovation, and enhance the resonance between people my, people’s consumption types have changed and museums, so as to meet the growing spiritual and cul- Wgreatly. As the material life has been basically tural needs of the people and better inherit the excellent satised, the proportion of material consumption has been traditional culture. The cultural innovation of museums increasing; people pay more and more attention to spiri- faces great opportunities for development. -

Behind the Thriving Scene of the Chinese Art Market -- a Research

Behind the thriving scene of the Chinese art market -- A research into major market trends at Chinese art market, 2006- 2011 Lifan Gong Student Nr. 360193 13 July 2012 [email protected] Supervisor: Dr. F.R.R.Vermeylen Second reader: Dr. Marilena Vecco Master Thesis Cultural economics & Cultural entrepreneurship Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication Erasmus University Rotterdam 1 Abstract Since 2006, the Chinese art market has amazed the world with an unprecedented growth rate. Due to its recent emergence and disparity from the Western art market, it remains an indispensable yet unfamiliar subject for the art world. This study penetrates through the thriving scene of the Chinese art market, fills part of the gap by presenting an in-depth analysis of its market structure, and depicts the route of development during 2006-2011, the booming period of the Chinese art market. As one of the most important and largest emerging art markets, what are the key trends in the Chinese art market from 2006 to 2011? This question serves as the main research question that guides throughout the research. To answer this question, research at three levels is unfolded, with regards to the functioning of the Chinese art market, the geographical shift from west to east, and the market performance of contemporary Chinese art. As the most vibrant art category, Contemporary Chinese art is chosen as the focal art sector in the empirical part since its transaction cover both the Western and Eastern art market and it really took off at secondary art market since 2005, in line with the booming period of the Chinese art market. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter free, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedtbrough, substandard margin*, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g^ maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. A Beil & Howell Information Company 300 North Zee0 Road. Ann Arpor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800:521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. -

Tiananmen Square Fast Facts

HOME | CNN - ASIA PACIFIC Tiananmen Square Fast Facts CNN May 20, 12:34 pm News 2019 Here is some information about the events in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square on June 3-4, 1989. Facts: Tiananmen Square is located in the center of Beijing, the capital of China. Tiananmen means “gate of heavenly peace.” In 1989, after several weeks of demonstrations, Chinese troops entered Tiananmen Square on June 4 and fired on civilians. Estimates of the death toll range from several hundred to thousands. It has been estimated that as many as 10,000 people were arrested during and after the protests. Several dozen people have been executed for their parts in the demonstrations. Timeline: April 15, 1989 – Hu Yaobang, a former Communist Party leader, dies. Hu had worked to move China toward a more open political system and had become a symbol of democratic reform. April 18, 1989 – Thousands of mourning students march through the capital to Tiananmen Square, calling for a more democratic government. In the weeks that follow, thousands of people join the students in the square to protest against China’s Communist rulers. May 13, 1989 – More than 100 students begin a hunger strike in Tiananmen Square. The number increases to several thousand over the next few days. May 19, 1989 – A rally at Tiananmen Square draws an estimated 1.2 million people. General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, Zhao Ziyang, appears at the rally and pleads for an end to the demonstrations. May 19, 1989 – Premier Li Peng imposes martial law. June 1, 1989 – China halts live American news telecasts in Beijing, including CNN. -

Masterwork by Li Keran to Take Centre Stage in Christie’S Hong Kong Modern Chinese Paintings Sale

For Immediate Release 7 May 2007 Press Contact: Victoria Cheung 852.2978.9919 [email protected] Dick Lee 852.2978.9966 [email protected] MASTERWORK BY LI KERAN TO TAKE CENTRE STAGE IN CHRISTIE’S HONG KONG MODERN CHINESE PAINTINGS SALE Li Keran (1907-1989) All the Mountains Blanketed in Red Scroll, mounted and framed Ink and colour on paper 131 x 84 cm. Dated autumn, September 1964 Estimate on request Fine Modern Chinese Paintings 28 May 2007 Hong Kong – An impressive selection of works by leading Chinese artists including Li Keran will be offered in the Fine Modern Chinese Paintings sale at Christie’s Hong Kong on 28 May. The works on offer will amaze art collectors with their exceptional quality and captivating themes. Also included in the sale are paintings of impeccable provenance from private collections. In this Spring auctions series, Christie's Hong Kong will introduce a real-time multi-media auction service Christie’s LIVE™, becoming the first international auction house in Asia to offer fine art through live online auctions. Christie’s LIVE™ enables collectors around the world to bid from their personal computers while enjoying the look, sound and feel of the sale. The star lot of the sale is All the Mountains Blanketed in Red by Li Keran (1907–1989) (Estimate on request, Lot 1088). From 1962 to 1964, Li produced a series of seven paintings that took on the theme of ‘All the mountains are blanketed in red and forests are totally dyed’, a phrase from Mao Zedong’s (1892–1976) poem Chang Sha (To the Tune of Spring Beaming in a Garden). -

UC Berkeley Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review

UC Berkeley Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review Title "Music for a National Defense": Making Martial Music during the Anti-Japanese War Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7209v5n2 Journal Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review, 1(13) ISSN 2158-9674 Author Howard, Joshua H. Publication Date 2014-12-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California “Music for a National Defense”: Making Martial Music during the Anti-Japanese War Joshua H. Howard, University of Mississippi Abstract This article examines the popularization of “mass songs” among Chinese Communist troops during the Anti-Japanese War by highlighting the urban origins of the National Salvation Song Movement and the key role it played in bringing songs to the war front. The diffusion of a new genre of march songs pioneered by Nie Er was facilitated by compositional devices that reinforced the ideological message of the lyrics, and by the National Salvation Song Movement. By the mid-1930s, this grassroots movement, led by Liu Liangmo, converged with the tail end of the proletarian arts movement that sought to popularize mass art and create a “music for national defense.” Once the war broke out, both Nationalists and Communists provided organizational support for the song movement by sponsoring war zone service corps and mobile theatrical troupes that served as conduits for musicians to propagate their art in the hinterland. By the late 1930s, as the United Front unraveled, a majority of musicians involved in the National Salvation Song Movement moved to the Communist base areas. Their work for the New Fourth Route and Eighth Route Armies, along with Communist propaganda organizations, enabled their songs to spread throughout the ranks. -

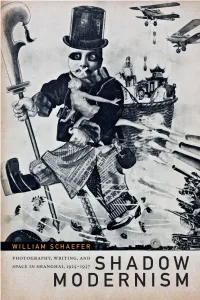

Read the Introduction

William Schaefer PhotograPhy, Writing, and SPace in Shanghai, 1925–1937 Duke University Press Durham and London 2017 © 2017 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Text designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schaefer, William, author. Title: Shadow modernism : photography, writing, and space in Shanghai, 1925–1937 / William Schaefer. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and ciP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017007583 (print) lccn 2017011500 (ebook) iSbn 9780822372523 (ebook) iSbn 9780822368939 (hardcover : alk. paper) iSbn 9780822369196 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcSh: Photography—China—Shanghai—History—20th century. | Modernism (Art)—China—Shanghai. | Shanghai (China)— Civilization—20th century. Classification: lcc tr102.S43 (ebook) | lcc tr102.S43 S33 2017 (print) | ddc 770.951/132—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007583 Cover art: Biaozhun Zhongguoren [A standard Chinese man], Shidai manhua (1936). Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University Libraries. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the University of Rochester, Department of Modern Languages and Cultures and the College of Arts, Sciences, and Engineering, which provided funds toward the publication -

Golden Week Tourism and Beijing City

Golden Week Tourism and Beijing City ZHAO Jian-Tong, ZHU Wen-Yi Abstract: Tourist Industry plays an important role in Beijing’s national economy and social development. After the Beijing Olympic Games, the urban space of Beijing has turned into a new development stage, and the city’s tourist attractiveness has been further improved. Beijing has been the hottest tourist city nationwide in National Day Golden Week for years running, and the new characteristics and problems of its urban space are concentratedly shown during the holiday. Through a brief summary of the tourist status and related urban spaces of Beijing, which is examined along the Golden Week tours, the new development stage of Beijing urban space will be discussed. Keywords: Beijing, Golden Week, Tourism, Urban Space The 7-day holiday of National Day, since set up in 1999, has rapidly become the most popular time for travel in China, both in terms of number and amassing of tourists. The main scenic spots and regions in Beijing are continuously facing with “blowouts”, and the record of the city’s tourist income has been constantly broken. The National Day holiday is the true “GOLDEN WEEK” of tourism in Beijing. After the 2008 Olympic Games, the city’s tourist attractiveness has been further improved. Beijing has been the hottest destination city nationwide in Golden Week from 2008 to 2010 (Figure 1); Tian An Men, the Forbidden City and the Great Wall stood on the top list of scenic spots concerned (Figure 2). Figure 1: Top three domestic destination cities in Golden Week in China, from 2008 to 2010 Figure 2: Beijing’s most popular scenic spots in Golden Week, from 2008 to 2010 Again in 2011, Beijing was crowned as the No.1 destination city nationwide in Golden Week1, and the city experienced another tourism peak. -

MANHUA MODERNITY HINESE CUL Manhua Helped Defi Ne China’S Modern Experience

CRESPI MEDIA STUDIES | ASIAN STUDIES From fashion sketches of Shanghai dandies in the 1920s, to phantasma- goric imagery of war in the 1930s and 1940s, to panoramic pictures of anti- American propaganda rallies in the 1950s, the cartoon-style art known as MODERNITY MANHUA HINESE CUL manhua helped defi ne China’s modern experience. Manhua Modernity C TU RE o ers a richly illustrated and deeply contextualized analysis of these il- A lustrations from the lively pages of popular pictorial magazines that enter- N UA D tained, informed, and mobilized a nation through a half century of political H M T and cultural transformation. N H O E A “An innovative reconceptualization of manhua. John Crespi’s meticulous P study shows the many benefi ts of interpreting Chinese comics and other D I M C illustrations not simply as image genres but rather as part of a larger print E T culture institution. A must-read for anyone interested in modern Chinese O visual culture.” R R I CHRISTOPHER REA, author of The Age of Irreverence: A New History A of Laughter in China L N “A rich media-centered reading of Chinese comics from the mid-1920s T U U I I through the 1950s, Manhua Modernity shifts the emphasis away from I R R T T ideological interpretation and demonstrates that the pictorial turn requires T N N examinations of manhua in its heterogenous, expansive, spontaneous, CHINESE CULTURE AND THE PICTORIAL TURN AND THE PICTORIAL CHINESE CULTURE Y and interactive ways of engaging its audience’s varied experiences of Y fast-changing everyday life.” YINGJIN ZHANG, author of Cinema, Space, and Polylocality in a Globalizing China JOHN A. -

Pressemitteilung ENGLISCH

Press release For immediate release Berlin, 26 November 2010 ‘The Art of the Enlightenment’ in Beijing German Museums present Exhibition on the Art of the Enlightenment in the Largest Museum in the World at Tiananmen Square; Stiftung Mercator organizes Parallel Event Series ‘Enlightenment in Dialogue’ An exhibition by the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden and Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen Munich, in conjunction with the National Museum of China in Beijing Spring 2011 – spring 2012 Berlin – In spring 2011 three major German museum bodies – the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden and the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen Munich – will join forces with the National Museum of China to present an exhibition on the art of the Enlightenment, to be held in Beijing. The exhibition reveals the unfolding artistic and intellectual curiosity and openness of mind which characterized this era in European history. It is furthermore the first international exhibition to be hosted at the National Museum of China when it reopens in early 2011 after the completion of an extensive refurbishment and expansion program. The initial agreement on the long-term presentation of works of art by the three German museum partners in the National Museum of China was signed by the then German President Horst Köhler and his Chinese counterpart Hu Jintao in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing in May 2007. The joint exhibition project between the three German museum bodies and the National Museum of China was then formally agreed to in writing on 29 January 2009, during a ceremony in the German Chancellery in Berlin which was attended by the German Chancellor Angela Merkel and the Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao. -

National Museum of China Reopened

National Museum of China reopened 2020/05/04 CGTN As the COVID-19 pandemic has eased in China, museums in Beijing reopened on May 1. Among these popular destinations are the Palace Museum and the National Museum of China. After closing for almost 100 days to help contain the spread of COVID-19, the Palace Museum, also known as the Forbidden City, opened its doors on Friday. However, the Palace administration has enforced a cap of 5,000 visitors per day to follow the social distancing measures. Tickets need to be booked online in advance. For now only outdoor spaces in the compound are open to public. Visitors must have their body temperature checked and scan a QR code to confirm their health status before entering the ancient site. The National Museum of China, which is right across the road, is taking similar precautions. Gu Jiandong, deputy Party secretary of the National Museum of China's CPC Committee, told CGTN: "Among the ongoing exhibitions, I especially recommend our 'Ancient China' exhibition, because it's the only one in the country in which you get to see 5,000 years of our country's cultural legacy in its full glory." For Beijing residents, who have been in self-quarantine for months, visiting museums is a popular choice for entertainment and education during the Labor Day holiday. A visitor praised the efforts made by the authorities in managing crowds. "The museum used to admit 30,000 people a day, but now only 3,000 visitors are allowed. So we want to take this opportunity to better appreciate the exhibition about ancient China," he said.