Architectural History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Sublime Modularity

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Sublime Modularity A graduate project submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements For the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Art, Visual Arts By Curtis Taylor May 2017 i A graduate project of Curtis Taylor is approved: __________________________________________ ____________ Christian Tedeschi, M.F.A. Date __________________________________________ ____________ Lesley Krane, M.F.A. Date __________________________________________ ____________ Michelle Rozic, M.F.A., Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Acknowledgements To Genevieve, All I have earned I owe to you. I could not have done this without your support. You have guided me through this process and kept me sane along the way. Thank you, my love. Evan, Sophie and Inès, Thank you for all your patience throughout this program. I can’t express how much your understanding has helped me complete this program. Thank you. Mom and Dad, You have always been there for me with encouragement and inspiration. The genetic material to keep me moving and creating is especially appreciated! Monica and Jerry, You have always supported me, even before I knew I wanted to go on this adventure! Michelle Rozic, Thank you for all your support, encouragement. Your expectations have raised the expectations I now hold for myself and made me a better artist. Lesley Krane, You have always been so welcoming and gracious with your support; especially that one time in review when you commented about the absence of my, then secret, abstract prints. Christian Tedeschi, Thank you for introducing me to Googie architecture; an important puzzle piece which opened a new understanding of myself and my art. -

Brief History of Architecture in N.C. Courthouses

MONUMENTS TO DEMOCRACY Architecture Styles in North Carolina Courthouses By Ava Barlow The judicial system, as one of three branches of government, is one of the main foundations of democracy. North Carolina’s earliest courthouses, none of which survived, were simple, small, frame or log structures. Ancillary buildings, such as a jail, clerk’s offi ce, and sheriff’s offi ce were built around them. As our nation developed, however, leaders gave careful consideration to the structures that would house important institutions – how they were to be designed and built, what symbols were to be used, and what building materials were to be used. Over time, fashion and design trends have changed, but ideals have remained. To refl ect those ideals, certain styles, symbols, and motifs have appeared and reappeared in the architecture of our government buildings, especially courthouses. This article attempts to explain the history behind the making of these landmarks in communities around the state. Georgian Federal Greek Revival Victorian Neo-Classical Pre – Independence 1780s – 1820 1820s – 1860s 1870s – 1905 Revival 1880s – 1930 Colonial Revival Art Deco Modernist Eco-Sustainable 1930 - 1950 1920 – 1950 1950s – 2000 2000 – present he development of architectural styles in North Carolina leaders and merchants would seek to have their towns chosen as a courthouses and our nation’s public buildings in general county seat to increase the prosperity, commerce, and recognition, and Trefl ects the development of our culture and history. The trends would sometimes donate money or land to build the courthouse. in architecture refl ect trends in art and the statements those trends make about us as a people. -

Tiki Scholar Jeff Berry Burns a Torch for a Rum-Soaked Chapter of Americana

strawberry-prosecco sorbet | PORTUGaL | homemade bitters Market Fresh Celebrate the Best of the Season With Irresistible Summer Drinks Urban Wineries Crisp, Cool, Old-style American Lagers $4.95 US / $6.95 CAN mAY/ JUN 2007 The Best New Coffee CitieS 28 IMBIBe mAY/JUNE 07 Not Bad for a BEACHBUM Tiki scholar Jeff Berry burns a torch for a rum-soaked chapter of Americana Story by PAuL CLARKe Photos by PETE StARMAN hen your life’s work is researching a topic that Orleans native named Ernest Raymond Beaumont Gantt, many people consider campy at best and tacky who opened a small bar in Hollywood in 1934, decorated it W at worst, you have a tough job. with nautical castoffs and souvenirs from his South Pacific Jeff Berry has a tough job. travels, and called it Don the Beachcomber’s. Gantt, who But as a self-described “professional bum” who publicly later changed his name to Donn Beach, created an exotic expresses disdain for labor of any sort, Berry would never environment—replete with elaborate rum-based libations let you know it. A former journalist, screenwriter and film- such as the potent Dr. Funk, the flaming Volcano Bowl maker, and the author of three books on exotic cocktails and and his most legendary creation, the Zombie—that quickly cuisine, including Beachbum Berry’s Grog Log and Intoxica! became fashionable among Hollywood’s nobility, attracting (a fourth, Sippin’ Safari, comes out in June), Berry has made customers such as Charlie Chaplin, Clark Gable and Howard it his mission to rescue what he calls “faux-tropical” drinks Hughes. -

Mountain View and Los Altos

MOUNTAIN VIEW VOICE | 2017 EDITION Mountain View and Los Altos PROFILES, MAPS AND VITAL FACTS OF FEATURED NEIGHBORHOODS IN THE COMMUNITY mv-voice.com Experience is Everything OVER 1,600 HOMES SOLD IN 30 YEARS Mountain View, Los Altos & Surrounding Areas 31 12 diamondcertifi ed.org www.HowardBloom.com [email protected] 650.947.4780 CalBRE# 00893793 2 | Mountain View Voice | Neighborhoods Thinking of Taking Advantage of the Spring Market? If so, it’s not too soon to start the process of preparing your home for sale. Our services range from minor touch-up to a complete makeover, with concierge service that includes: QRepairs and upgrades QLandscape and design QInterior design QStaging QProfessional Photography & Video QFull Page Newspaper Ads QPrint Marketing Whether your home is market-ready or in need of some TLC,, we offer strategic options designed to generate the highest possible sales price foror yyourour home. Derk is a born and raised Palo Altan, and the top producing agentagent in Alain Realtors Palo Alto office. Call today to schedule a consultation,ultation, and leverage the “Home Team” advantage offered by a true localocal who knows your neighborhood inside and out. Local Knowledge, Local Resources, Global Reach. Derk Brill Call Derk to schedule a one-on-one meeting at CELL 650.814.0478 Alain Pinel Realtors 578 University Avenue Palo Alto CalBRE# 01256035 [email protected] www.DerkBrill.com Neighborhoods | Mountain View Voice | 3 Judy Bogard-Tanigami Judy 650.207.2111 [email protected] CalBRE# 00298975 Sheri Bogard-Hughes 650.279.4003 [email protected] CalBRE# 01060012 Cindy Bogard-O’Gorman 650.924.8365 [email protected] Cindy Sheri CalBRE# 01918407 ConsultantsInRealEstate.com TOP REASONS TO WORK WITH OUR TEAM We Provide Individual Expertise Combined in a Successful Team Approach Ranked Among Top Agents “We knew that we were in good hands, and we also knew that you were in the Wall Street Journal for the best in the business. -

Souvenir Tiki Mugs

Souvenir Tiki Mugs ~8 Moai Mug So you can make your own awesome tiki drinks! ~15 Vintage Otagin Mercantile Company Mai Tai Mug Welcome to this humble ~10 if bought in addition to a drink tiki bar, a place where We happened upon these vintage Mai Tai mugs! tiki gods come from South America and Mai Tais are taken seriously but not much else is. May our drinks take you to a land where laziness is a virtue and hedonism reigns supreme. -Viracocha 301 N. Peters St. Above Felipe’s in the French Quarter NOLA 70117 504-267-4406 OPEN Tues - Thur 5PM – Midnight – check Facebook or Twitter - http://www.facebook.com/TikiTolteca http://twitter.com/TikiTolteca Tiki Alchemy Latiki ~10 Last Guinea Pig in Cuzco In this drink, pisco takes a stand in the world of tiki. For the story behind the name, you must visit the Cathedral of Santo Domingo in Peru (or you could just ask the bartender). –created by Nathan using Barsol Q. Pisco Small Plates ~9 Subtropical Itch When Trader Dick went south last year, he got an itch upon his ear The locals sold a ~7 Sweet Corn Tamale Cakes potion brown, which made him itch much further down. And then they all Fresh corn, masa harina, salsa verde, laughed…but at least it tastes good. Mexican crema picante, avocado -created by Trader Dick using Bulleit Rye and Goslings Rum ~22 Escorpion punch (serves 2 – 3) ~8 Classic Rumaki In the espectacular land of mezcal, escorpions do more with their hands then just Hickory bacon-wrapped chicken liver, pinch. -

Guggenheim Musem, Ground Level Interior

landmarks Preservation Commission August 14, 1990; Designation List 226 LP-1775 GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM, GROUND LEVEL INTERIOR consisting of the entrance loggia (nCM the bookstore), the entrance vestibule, the main gallery space including the fountain, adrnissionjinfo:rma.tion desk, and telephone alcove, and the coat room foyer; AUDITORIUM LEVEL INTERIOR consisting of the staircase in the triangular stai:rhall leading from the auditorium level to the ground level, the elevator foyer, the auditorium, the auditorium mezzanine, the stairs and areas providing access to the auditorium mezzanine, and the stage/platform; the GROUND 1EVEL 'IHROUGH SIXTH LEVEL INTERIORS, up to and including the glass dome, consisting of the continuous rarrp; the space enclosed by the continuous rarrp; the adjacent gallery spaces, among them the grand gallery at the first and second levels, including the fixed planters at the bottom and top of the first level, at the top of the second level, and at the top of the third level, and the skylights; the elevator foyers; and the elevator cabs; the GROUND LEVEL THROUGH FaJRIH LEVEL INTERIORS consisting of the triangular stairhall and staircases which terminate at the top of the fourth level which is the beginning of the fifth level; the SEa:>ND LEVEL INTERIOR consisting of the Justin K. Thannhauser Wing; the SIXTH LEVEL INTERIOR consisting of the triangular gallery adjacent to the elevator shaft; and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces, included but not limited to, floor surfaces, wall surfaces, ceiling surfaces, doors, wind.CMS, brass railings, triangular light fixtures, trough light fixtures, signs, and metal museum seal, 1071 Fifth Avenue, Manhattan. -

Toward a Framework for Preserving Mid-Century Modern Resources: an Examination of Public Perceptions of the Sarasota School of Architecture

TOWARD A FRAMEWORK FOR PRESERVING MID-CENTURY MODERN RESOURCES: AN EXAMINATION OF PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS OF THE SARASOTA SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE By NORA L. GALLAGHER A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 ©2011 Nora Louise Gallagher 2 To my family 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First I would like to thank my committee chair, Morris Hylton, III who showed much patience and dedication to the project. I would also like to thank Sara Katherine Williams who came onto my committee last minute, but with no less dedication. I would also like to thank all of those who took the time out of their day at the beach or lunch schedule to answer my questions. Special thanks also goes Blair Mullins who not only helped with interviewing, but inspired motivation in me. Finally, I would like to thank my parents, Phil and Linda Gallagher who used to force me to work on house projects and repairs – without this I would not have an appreciation for what makes a building important, the memories which are made there. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 4 LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................ 7 LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... 8 ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................. -

Mid-Century Modern Architecture of Norwich

COVID-19 Response Following guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and state and local public health authorities, park operations continue to adapt to changing conditions while maintaining public access, particularly outdoor spaces. Before visiting a park, please check the park website to determine its operating status. Updates about the overall NPS response to COVID-19, including safety information, are posted on www.nps.gov/coronavirus. Please recreate responsibly. National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Weekly List 20200925 KEY: State, County, Property Name, Address/Boundary, City, Vicinity, Reference Number, NHL, Action, Date, Multiple Name ALASKA, MATANUSKA-SUSITNA BOROUGH, Wasilla Depot, Parks Hwy. and Knik Rd., Wasilla, MV77000218, PROPOSED MOVE APPROVED, 9/21/2020 ARKANSAS, WASHINGTON COUNTY, Woolsey Farmstead Cemetery, 535 South Broyles Rd., Fayetteville, SG100005595, LISTED, 9/21/2020 CONNECTICUT, NEW HAVEN COUNTY, Pinto, William, House, 275 Orange St., New Haven, MV85002316, PROPOSED MOVE APPROVED, 9/21/2020 IOWA, BENTON COUNTY, Preston’s Station Historic District, 402 4th Ave., Belle Plaine, SG100005572, LISTED, 9/21/2020 IOWA, GRUNDY COUNTY, Grundy Center High School, 1001 8th St., Grundy Center, SG100005565, LISTED, 9/18/2020 IOWA, MUSCATINE COUNTY, Ijem Avenue Commercial Historic District, Ijem Ave. between Railroad St. and Main St., Nichols, SG100005566, LISTED, 9/18/2020 IOWA, POLK COUNTY, Acadian Manor Historic District, 2801- 2815 Grand Ave., Des Moines, SG100005567, LISTED, 9/18/2020 IOWA, POLK COUNTY, Argonne Building, 1723 Grand Ave. (1723-1733 Grand Ave., plus 515 18th St.), Des Moines, SG100005608, LISTED, 9/24/2020 IOWA, SCOTT COUNTY, Davenport Downtown Commercial Historic District, 2nd St. -

A. Quincy Jones: Building for Better Living Free

FREE A. QUINCY JONES: BUILDING FOR BETTER LIVING PDF Brooke Hodge | 224 pages | 25 Jun 2013 | PRESTEL | 9783791352657 | English | Munich, Germany A. Quincy Jones: Building for Better Living – Hammer Store Quincy Jones, Frederick E. Emmons and John L. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation, First Edition. Gray cloth stamped in black. Photo illustrated dust jacket. Color cover photograph by Julius Shulman. A truly rare book authored by a pair of architects whose roles in the development of the postwar modern residential movement cannot be overstated. Small ink A. Quincy Jones: Building for Better Living inscription to front free endpaper, otherwise a fine copy in a fine dust jacket. Sketches By Rudy Veland. This book is dedicated to Joseph L. Eichler: "a truly progressive builder, whose untiring efforts have advanced greatly the concepts of todays' development houses, this book is A. Quincy Jones: Building for Better Living dedicated. As Joe Eichler was initiating his fledgling real estate development in the Highlands, the X served as his promotional attraction to reel in crowds for his company's open houses. It was also a vehicle for showcasing new technology such as steel construction, indoor gardens, and other custom elements that was unique or unusual to the homebuilding industry. Here's the importance of Eichler to the authors: Eichler Homes are represented by 70 entries A. Quincy Jones: Building for Better Living the index. The Research Village of Barrington, Illinois is also covered in detail. The Research Village was a building project of United States Gypsum, which sponsored six architects and A. Quincy Jones: Building for Better Living to each design and build a single-family residence. -

Brutalism? Some Remarks About a Polemical Name, Its Definition, and Its Use to Designate a Brazilian Architectural Trend

Published at En Blanco n.9/2012 pages 130-2 Avaliable at: http://www.tccuadernos.com/enblanco_numero.php?id=86 Brutalism? Some Remarks About a Polemical Name, its Definition, and its Use to Designate a Brazilian Architectural Trend Ruth Verde Zein [email protected] Mackenzie University São Paulo, Brazil Abstract The term Brutalism is both used and ignored in the architectural literature of the second half of the twentieth century. A thorough analysis of the term shows that it does not have a single, agreed-upon meaning. Although its definition and frequent use have not provided an unequivocal characterization of a Brutalist “essence,” to use Reyner Banham’s words, there seems to be no shortage of architecture identified as Brutalist, even if they are only superficially related. Paradoxically, instead of disregarding the term as inappropriate or vague, we might consider it adequate if we agree that what is common to all the architecture referred to as Brutalist is nothing more than their appearance. By accepting a non-essentialist definition of this movement, one may correctly apply the term to a number of different works, from different places, designed between 1950 and 1970. For the most part, what really connects these buildings is not their essence but their surface, not their inner characteristics but their extrinsic ones. Such a straightforward definition, encompassing the broad variety of Brutalist works, has the merit of providing a working definition of a broadly influential if understudied movement in modern architecture. 1 Fifty years after Brasilia’s inauguration in 1960, Brazilian architecture remains stuck in the same frozen images of a glorious moment in history. -

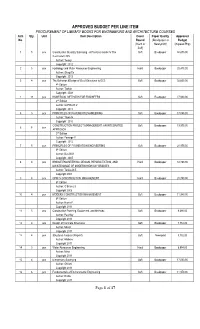

APPROVED BUDGET PER LINE ITEM PROCUREMENT of LIBRARY BOOKS for ENGINEERING and ARCHITECTURE COURSES Item Qty

APPROVED BUDGET PER LINE ITEM PROCUREMENT OF LIBRARY BOOKS FOR ENGINEERING AND ARCHITECTURE COURSES Item Qty. Unit Item Description Cover Paper Quality Approved No. Bound (Bookpaper or Budget (Hard or Newsprint) (in peso/Php) Soft) 1 5 pcs Construction Quantity Surveying - A Practical Guide for The Soft Bookpaper 30,475.00 Contractor's QS Author: Towey Copyright 2012 2 5 pcs Hydrology and Water Resources Engineering Hard Bookpaper 20,475.00 Author: Shagufta Copyright 2013 3 4 pcs The Behavior &Design of Steel Structures to EC3 Soft Bookpaper 30,600.00 4th Edition Author: Trahair Copyright 2008 4 14 pcs NUMERICAL METHODS FOR ENGINEERS Soft Bookpaper 27,930.00 2nd Edition Author: Griffiths D.V. Copyright 2011 5 3 pcs PRINCIPLES OF PAVEMENT ENGINEERING Soft Bookpaper 17,085.00 Author: Thom N. Copyright 2010 CONSTRUCTION PROJECT MANAGEMENT: AN INTEGRATED Soft Bookpaper 19,975.00 6 5 pcs APPROACH 2nd Edition Author: Fewings P. Copyright 2012 7 5 pcs PRINCIPLES OF FOUNDATION ENGINEERING Soft Bookpaper 20,975.00 6th Edition Author: Das B.M. Copyright 2007 8 4 pcs BRIDGE ENGINEERING: DESIGN, REHABILITATION, AND Hard Bookpaper 32,780.00 MAINTENANCE OF MODERN HIGHWAY BRIDGES Author: Tonias D.E. Copyright 2007 9 4 pcs CPM IN CONSTRUCTION MANAGEMENT Hard Bookpaper 28,780.00 6th Edition Author: O’Brien J.J. Copyright 2006 10 4 pcs MODERN CONSTRUCTION MANAGEMENT Soft Bookpaper 11,980.00 6th Edition Author: Harris F. Copyright 2013 11 5 pcs Construction Planning, Equipment, and Methods Soft Bookpaper 9,690.00 Author: Peurifoy Copyright 2011 12 4 pcs -

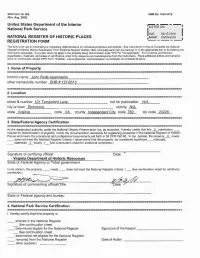

Nomination Form, “The Tuckahoe Apartments.” (14 June 2000)

NPS Form 10- 900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. Aug. 2002) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Fonn (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "NIA" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. ...................................................... - - - ...........................................................................................................................................................................1. Name of Property historic name John Rolfe Apartments other nameslsite number DHR # 127-6513 ---------- 2. Location street & number 101 Tem~sfordLane not for publication NIA city or town Richmond vicinity state Virqinia code & county Independent Citv code 760 zip code 23226 3. StatelFederal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Presewation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this