A Land and Resource Management Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Cascades Contested Terrain

North Cascades NP: Contested Terrain: North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History NORTH CASCADES Contested Terrain North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History CONTESTED TERRAIN: North Cascades National Park Service Complex, Washington An Administrative History By David Louter 1998 National Park Service Seattle, Washington TABLE OF CONTENTS adhi/index.htm Last Updated: 14-Apr-1999 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/noca/adhi/[11/22/2013 1:57:33 PM] North Cascades NP: Contested Terrain: North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History (Table of Contents) NORTH CASCADES Contested Terrain North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Cover: The Southern Pickett Range, 1963. (Courtesy of North Cascades National Park) Introduction Part I A Wilderness Park (1890s to 1968) Chapter 1 Contested Terrain: The Establishment of North Cascades National Park Part II The Making of a New Park (1968 to 1978) Chapter 2 Administration Chapter 3 Visitor Use and Development Chapter 4 Concessions Chapter 5 Wilderness Proposals and Backcountry Management Chapter 6 Research and Resource Management Chapter 7 Dam Dilemma: North Cascades National Park and the High Ross Dam Controversy Chapter 8 Stehekin: Land of Freedom and Want Part III The Wilderness Park Ideal and the Challenge of Traditional Park Management (1978 to 1998) Chapter 9 Administration Chapter 10 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/noca/adhi/contents.htm[11/22/2013 -

Wilderness Visitors and Recreation Impacts: Baseline Data Available for Twentieth Century Conditions

United States Department of Agriculture Wilderness Visitors and Forest Service Recreation Impacts: Baseline Rocky Mountain Research Station Data Available for Twentieth General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-117 Century Conditions September 2003 David N. Cole Vita Wright Abstract __________________________________________ Cole, David N.; Wright, Vita. 2003. Wilderness visitors and recreation impacts: baseline data available for twentieth century conditions. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-117. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 52 p. This report provides an assessment and compilation of recreation-related monitoring data sources across the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). Telephone interviews with managers of all units of the NWPS and a literature search were conducted to locate studies that provide campsite impact data, trail impact data, and information about visitor characteristics. Of the 628 wildernesses that comprised the NWPS in January 2000, 51 percent had baseline campsite data, 9 percent had trail condition data and 24 percent had data on visitor characteristics. Wildernesses managed by the Forest Service and National Park Service were much more likely to have data than wildernesses managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Fish and Wildlife Service. Both unpublished data collected by the management agencies and data published in reports are included. Extensive appendices provide detailed information about available data for every study that we located. These have been organized by wilderness so that it is easy to locate all the information available for each wilderness in the NWPS. Keywords: campsite condition, monitoring, National Wilderness Preservation System, trail condition, visitor characteristics The Authors _______________________________________ David N. -

Vaccinium Processing in the Washington Cascades

Joumul of Elhoobiology 22(1): 35--60 Summer 2002 VACCINIUM PROCESSING IN THE WASHINGTON CASCADES CHERYL A 1viACK and RICHARD H. McCLURE Heritage Program, Gifford Pirwhot National Forest, 2455 HighlL¥1lf 141, Dou! Lake, WA 98650 ABSTRACT,~Among Ihe native peoples of south-central Washington, berries of the genus Vaccil1ium hold a signHicant place among traditional foods. In the past, berries were collected in quantity at higher elevations in the central Cascade Mmmtains and processed for storage. Berries were dried along a shallow trench using indirect heat from d smoldering log. To date, archaeological investigations in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest have resulted in lhe identil1cation of 274 Vatcin;um drying features at 38 sites along the crest of the Cascades. Analyses have included archaeobotanical sampling,. radiocarbon dating. and identification of related features, incorporating ethnohistonc and ethnographic studies, Archae ological excavations have been conducted at one of the sites. Recent invesHgations indicate a correlation behveen high feature densities and specific plant commu nities in the mountain heml()(~k zone. The majority of the sites date from the historic period, but evidence 01 prehistoflc use is also indicated, Key words: berries, Vaccinium~ Cascade rv1ountains, ethnornstory, ardtaeubotanical record. RESUMEN,~-Entre los indig~.nas del centro-sur de Washinglon, las bayas del ge nero Vaccinium occupan un 1ugar significati''ilo entre los alirnentos tradicionales. En 121 pasado, estas bayas se recogfan en grandes canlidades en las zonas elevadas del centro de las rvtontanas de las Cascadas y se procesaban para e1 almacena miento, Las bayas Be secabl''ln n 10 largo de una zanja usando calor indirecto prod uddo POt un tronco en a"'icuas. -

Flood Basalts and Glacier Floods—Roadside Geology

u 0 by Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Information Circular 90 January 1996 WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENTOF Natural Resources Jennifer M. Belcher - Commissioner of Public Lands Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor FLOOD BASALTS AND GLACIER FLOODS: Roadside Geology of Parts of Walla Walla, Franklin, and Columbia Counties, Washington by Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Information Circular 90 January 1996 Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor Division of Geology and Earth Resources WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Jennifer M. Belcher-Commissio11er of Public Lands Kaleeo Cottingham-Supervisor DMSION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Raymond Lasmanis-State Geologist J. Eric Schuster-Assistant State Geologist William S. Lingley, Jr.-Assistant State Geologist This report is available from: Publications Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources P.O. Box 47007 Olympia, WA 98504-7007 Price $ 3.24 Tax (WA residents only) ~ Total $ 3.50 Mail orders must be prepaid: please add $1.00 to each order for postage and handling. Make checks payable to the Department of Natural Resources. Front Cover: Palouse Falls (56 m high) in the canyon of the Palouse River. Printed oo recycled paper Printed io the United States of America Contents 1 General geology of southeastern Washington 1 Magnetic polarity 2 Geologic time 2 Columbia River Basalt Group 2 Tectonic features 5 Quaternary sedimentation 6 Road log 7 Further reading 7 Acknowledgments 8 Part 1 - Walla Walla to Palouse Falls (69.0 miles) 21 Part 2 - Palouse Falls to Lower Monumental Dam (27.0 miles) 26 Part 3 - Lower Monumental Dam to Ice Harbor Dam (38.7 miles) 33 Part 4 - Ice Harbor Dam to Wallula Gap (26.7 mi les) 38 Part 5 - Wallula Gap to Walla Walla (42.0 miles) 44 References cited ILLUSTRATIONS I Figure 1. -

VGP) Version 2/5/2009

Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS (VGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act (CWA), as amended (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.), any owner or operator of a vessel being operated in a capacity as a means of transportation who: • Is eligible for permit coverage under Part 1.2; • If required by Part 1.5.1, submits a complete and accurate Notice of Intent (NOI) is authorized to discharge in accordance with the requirements of this permit. General effluent limits for all eligible vessels are given in Part 2. Further vessel class or type specific requirements are given in Part 5 for select vessels and apply in addition to any general effluent limits in Part 2. Specific requirements that apply in individual States and Indian Country Lands are found in Part 6. Definitions of permit-specific terms used in this permit are provided in Appendix A. This permit becomes effective on December 19, 2008 for all jurisdictions except Alaska and Hawaii. This permit and the authorization to discharge expire at midnight, December 19, 2013 i Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 William K. Honker, Acting Director Robert W. Varney, Water Quality Protection Division, EPA Region Regional Administrator, EPA Region 1 6 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, Barbara A. -

In This Issue: President’S Message and Study Weekend P 2 Watching Washington Butterflies P 3 Are Cultivars Bad Nectar Sources? P 6

Volume 20, Number 1 February 2019 G’num* The newsletter of the Washington Butterfly Association P.O. Box 31317 Seattle WA 98103 http://wabutterflyassoc.org Facebook: Washington Butterfly Association. Instagram: #washingtonbutterflies (anyone can use this hashtag) *G’num is the official greeting of WBA. It is derived from the name of common Washington butterfly food plants, of the genus Eriogonum. Papilio Papilio frigidorum. Seattle Snowpocalypse: Weiss during February’s Bellevue by Melanie New species spotted in In this issue: President’s Message and Study Weekend p 2 Watching Washington Butterflies p 3 Are Cultivars Bad Nectar Sources? p 6 Field Trip Schedule p 9 Upcoming Programs Wednesday Feb 20, Spokane: Dr. Gary Chang, Wool Carder Bees. Gary’s program will summarize his field study of the unusual behaviors of a relative newcomer to western landscapes, the European Wool Carder Bee, and it interac- tions with other species. Wednesday, March 6, Seattle: Maybe a second shot at the WSDOT Pollinator Habitat program cancelled in February. Wednesday, March 20, Spokane: Photography Workshop. Jeanne Dammarrell, Carl Barrentine and John Bau- mann team up to offer three perspectives on photography of butterflies and moths. They will chat about their preferred gear, methods, software and field locations in the hopes that many more area naturalists will be inspired to try their hands and lenses at lepidoptera photography! Jeanne's and Carl's photos have been extensively published in field re- sources in print and online. Wednesday, April 10, Seattle: TBA Wednesday, April 17, Spokane: David Droppers will present an update of his program "A Dichotomous Key for Identification of the Blues of Washington", in which all the species of the several genera of Washington's Polyom- matini tribe are described in vivid live photos and specimen photos. -

Layout 1 Copy 1

Events Contact Information Map and guide to points Festivals Goldendale From the lush, heavily forested April Earth Day Celebration – Chamber of Commerce of interest in and around Goldendale 903 East Broadway west side to the golden wheat May Fiddle Around the Stars Bluegrass 509 773-3400 W O Y L country in the east, Klickitat E L www.goldendalechamber.org L E Festival – Goldendale S F E G W N O June Spring Fest – White Salmon E L County offers a diverse selection Mt. Adams G R N O H E O July Trout Lake Festival of the Arts G J Chamber of Commerce Klickitat BICKLETON CAROUSEL July Community Days – Goldendale 1 Heritage Plaza, White Salmon STONEHENGE MEMORIAL of family activities and sight ~ Presby Quilt Show 509 493-3630 seeing opportunities. ~ Show & Shine Car Show www.mtadamschamber.com COUNTY July Nights in White Salmon City of Goldendale Wine-tasting, wildlife, outdoor Art & Fusion www.cityofgoldendale.com WASHINGTON Aug Maryhill Arts Festival sports, and breathtaking Sept Huckleberry Festival – Bingen Museums scenic beauty beckon visitors Dec I’m Dreaming of a White Salmon Carousel Museum–Bickleton Holiday Festival 509 896-2007 throughout the seasons. Y E L S Open May-Oct Thurs-Sun T E J O W W E G A SON R R Rodeos Gorge Heritage Museum D PETE O L N HAE E IC Y M L G May Goldendale High School Rodeo BLUEBIRDS IN BICKLETON 509 493-3228 HISTORIC RED HOUSE - GOLDENDALE June Aldercreek Pioneer Picnic and Open May-Sept Thurs-Sun Rodeo – Cleveland Maryhill Museum of Art June Ketcham Kalf Rodeo – Glenwood 509 773-3733 Aug Klickitat County Fair and Rodeo – Open Daily Mar 15-Nov 15 Goldendale www.maryhillmuseum.org Aug Cayuse Goldendale Jr. -

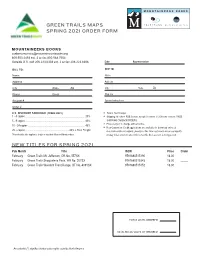

New Titles for Spring 2021 Green Trails Maps Spring

GREEN TRAILS MAPS SPRING 2021 ORDER FORM recreation • lifestyle • conservation MOUNTAINEERS BOOKS [email protected] 800.553.4453 ext. 2 or fax 800.568.7604 Outside U.S. call 206.223.6303 ext. 2 or fax 206.223.6306 Date: Representative: BILL TO: SHIP TO: Name Name Address Address City State Zip City State Zip Phone Email Ship Via Account # Special Instructions Order # U.S. DISCOUNT SCHEDULE (TRADE ONLY) ■ Terms: Net 30 days. 1 - 4 copies ........................................................................................ 20% ■ Shipping: All others FOB Seattle, except for orders of 25 books or more. FREE 5 - 9 copies ........................................................................................ 40% SHIPPING ON BACKORDERS. ■ Prices subject to change without notice. 10 - 24 copies .................................................................................... 45% ■ New Customers: Credit applications are available for download online at 25 + copies ................................................................45% + Free Freight mountaineersbooks.org/mtn_newstore.cfm. New customers are encouraged to This schedule also applies to single or assorted titles and library orders. prepay initial orders to speed delivery while their account is being set up. NEW TITLES FOR SPRING 2021 Pub Month Title ISBN Price Order February Green Trails Mt. Jefferson, OR No. 557SX 9781680515190 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass, WA No. 207SX 9781680515343 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Wasatch Front Range, UT No. 4091SX 9781680515152 18.00 _____ TOTAL UNITS ORDERED TOTAL RETAIL VALUE OF ORDERED An asterisk (*) signifies limited sales rights outside North America. QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE WASHINGTON ____ 9781680513448 Alpine Lakes East Stuart Range, WA No. 208SX $18.00 ____ 9781680514537 Old Scab Mountain, WA No. 272 $8.00 ____ ____ 9781680513455 Alpine Lakes West Stevens Pass, WA No. -

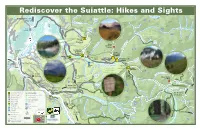

Rediscover the Suiattle: Hikes and Sights

Le Conte Chaval, Mountain Rediscover the Suiattle:Mount Hikes and Sights Su ia t t l e R o Crater To Marblemount, a d Lake Sentinel Old Guard Hwy 20 Peak Bi Buckindy, Peak g C reek Mount Misch, Lizard Mount (not Mountain official) Boulder Boat T Hurricane e Lake Peak Launch Rd na Crk s as C en r G L A C I E R T e e Ba P E A K k ch e l W I L D E R N E S S Agnes o Mountain r C Boulder r e Lake e Gunsight k k Peak e Cub Trailhead k e Dome e r Lake Peak Sinister Boundary e C Peak r Green Bridge Put-in C y e k Mountain c n u Lookout w r B o e D v Darrington i Huckleberry F R Ranger S Mountain Buck k R Green Station u Trailhead Creek a d Campground Mountain S 2 5 Trailhead Old-growth Suiattle in Rd Mounta r Saddle Bow Grove Guard een u Gr Downey Creek h Mountain Station lp u k Trailhead S e Bannock Cr e Mountain To I-5, C i r Darrington c l Seattle e U R C Gibson P H M er Sulphur S UL T N r S iv e uia ttle R Creek T e Falls R A k Campground I L R Mt Baker- Suiattle d Trailhead Sulphur Snoqualmie Box ! Mountain Sitting Mountain Bull National Forest Milk n Creek Mountain Old Sauk yo Creek an North Indigo Bridge C Trailhead To Suiattle Closure Lake Lime Miners Ridge White Road Mountain No Trail Chuck Access M Lookout Mountain M I i Plummer L l B O U L D E R Old Sauk k Mountain Rat K Image Universal C R I V E R Trap Meadow C Access Trail r Lake Suiattle Pass Mountain Crystal R e W I L D E R N E S S e E Pass N Trailhead Lake k Sa ort To Mountain E uk h S Meadow K R id Mountain T ive e White Chuck Loop Hwy ners Cre r R i ek R M d Bench A e Chuc Whit k River I I L Trailhead L A T R T Featured Trailheads Land Ownership S To Holden, E Other Trailheads National Wilderness Area R Stehekin Fire C Mountain Campgrounds National Forest I C Beaver C I F P A Fortress Boat Launch State Conservation Lake Pugh Mtn Mountain Trailhead Campground Other State Road Helmet Butte Old-growth Lakes Mt. -

Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest Geothermal Power Plant Environmental Impact Assessment Evan Derickson Western Washington University

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Huxley College Graduate and Undergraduate Huxley College of the Environment Publications Winter 2013 Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest geothermal power plant environmental impact assessment Evan Derickson Western Washington University Ethan Holzer Western Washington University Brandon Johansen Western Washington University Audra McCafferty Western Washington University Eric Messerschmidt Western Washington University See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/huxley_stupubs Part of the Environmental Studies Commons Recommended Citation Derickson, Evan; Holzer, Ethan; Johansen, Brandon; McCafferty, Audra; Messerschmidt, Eric; and Olsen, Kyle, "Mt. Baker- Snoqualmie National Forest geothermal power plant environmental impact assessment" (2013). Huxley College Graduate and Undergraduate Publications. 29. https://cedar.wwu.edu/huxley_stupubs/29 This Environmental Impact Assessment is brought to you for free and open access by the Huxley College of the Environment at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Huxley College Graduate and Undergraduate Publications by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Author Evan Derickson, Ethan Holzer, Brandon Johansen, Audra McCafferty, Eric Messerschmidt, and Kyle Olsen This environmental impact assessment is available at Western CEDAR: https://cedar.wwu.edu/huxley_stupubs/29 Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest Geothermal Power -

The Wild Cascades

THE WILD CASCADES Fall, 1984 2 The Wild Cascades PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE ONCE THE LINES ARE DRAWN, THE BATTLE IS NOT OVER The North Cascades Conservation Council has developed a reputation for consistent, hard-hitting, responsible action to protect wildland resources in the Washington Cascades. It is perhaps best known for leading the fight to preserve and protect the North Cascades in the North Cascades National Park, the Pasayten and Glacier Peak Wilderness Areas, and the Ross Lake and Lake Chelan National Recreation Areas. Despite the recent passage of the Washington Wilderness Act, many areas which deserve and require wilderness designation remain unprotected. One of the goals of the N3C must be to assure protection for these areas. In this issue of the Wild Cascades we have analyzed the Washington Wilderness Act to see what we won and what still hangs in the balance (page ). The N3C will continue to fight to establish new wilderness areas, but there is also a new challenge. Our expertise is increasingly being sought by government agencies to assist in developing appropriate management plans and to support them against attempts to undermine such plans. The invitation to participate more fully in management activities will require considerable effort, but it represents a challenge and an opportunity that cannot be ignored. If we are to meet this challenge we will need members who are either knowledgable or willing to learn about an issue and to guide the Board in its actions. The Spring issue of the Wild Cascades carried a center section with two requests: 1) volunteers to assist and guide the organization on various issues; and 2) payment of dues. -

Northeast Chapter Volunteer Hours Report for Year 2013-2014

BACK COUNTRY HORSEMEN OF WASHINGTON - Northeast Chapter Volunteer Hours Report for Year 2013-2014 Work Hours Other Hours Travel Equines Volunteer Name Project Agency District Basic Skilled LNT Admin Travel Vehicle Quant Days Description of work/ trail/trail head names Date Code Code Hours Hours Educ. Pub. Meet Time Miles Stock Used AGENCY & DISTRICT CODES Agency Code Agency Name District Codes for Agency A Cont'd A U.S.F.S. District Code District Name B State DNR OKNF Okanogan National Forest C State Parks and Highways Pasayten Wilderness D National Parks Lake Chelan-Sawtooth Wilderness E Education and LNT WNF Wenatchee National Forest F Dept. of Fish and Wildlife (State) Alpine Lakes Wilderness G Other Henry M Jackson Wilderness M Bureau of Land Management William O Douglas Wilderness T Private or Timber OLNF Olympic National Forest W County Mt Skokomish Wilderness Wonder Mt Wilderness District Codes for U.S.F.S. Agency Code A Colonel Bob Wilderness The Brothers Wilderness District Code District Name Buckhorn Wilderness CNF Colville National Forest UMNF Umatilla National Forest Salmo-Priest Wilderness Wenaha Tucannon Wilderness GPNF Gifford Pinchot National Forest IDNF Idaho Priest National Forest Goat Rocks Wilderness ORNF Oregon Forest Mt Adams Wilderness Indian Heaven Wilderness Trapper Wilderness District Codes for DNR Agency B Tatoosh Wilderness MBS Mt Baker Snoqualmie National Forest SPS South Puget Sound Region Glacier Peak Wilderness PCR Pacific Cascade Region Bolder River Wilderness OLR Olympic Region Clear Water Wilderness NWR Northwest Region Norse Peak Mt Baker Wilderness NER Northeast Region William O Douglas Wilderness SER Southeast Region Glacier View Wilderness Boulder River Wilderness VOLUNTEER HOURS GUIDELINES Volunteer Name 1.