OCR Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Horizon Tours

New Horizon Tours Presents INTOXICATING, INCREDIBLE INDIA MARCH 14 -MARCH 26, 2020 (LAX) Mar. 14, SAT: PARTICIPANTS from Los Angeles (LAX) board on Emirates air at 4.35PM Mar. 15, SUN: LAX PARTICIPANTS ARRIVE IN DUBAI AND CONNECT FLIGHT TO MUMBAI / Washington (IAD) participants depart at 11.10 AM Mar. 16, MON: ARRIVE MUMBAI Different times- LAX passengers arrive at 2.15AM (immediate occupancy of rooms- rooms reserved from Mar. 15). IAD passengers arrive at 2.00 PM- separate arrival transfers for each in Mumbai. Arrive in Mumbai, a cluster of seven islands derives its name from Mumba devi, the patron goddess of Koli fisher folk, the oldest habitants. Meeting assistance and transfer to Hotel. Rest of the day is free. Evening welcome dinner at roof top restaurant at Hotel near airport. HOTEL.OBEROI TRIDENT (Breakfast & Dinner for LAX passengers, Dinner only for IAD participants). Mar. 17, TUE: MUMBAI - CITY TOUR – BL Breakfast at Hotel. This morning embark on city tour of Mumbai visiting the British built Gateway of India, Bombay's landmark constructed in 1927 to commemorate Emperor George V's visit, the first State, ever to see India by a reigning monarch. Followed by a drive through the city to see the unique architecture, Mumbai University, Victoria Terminus, Marine Drive, Chowpatty Beach. Next stop at Hanging Gardens (now known as Sir K.P. Mehta Gardens), where the old English art of topiary is practiced. Continue to the Dhobi Ghat, an open-air laundry where washmen physically clean and iron hundreds of items of clothing, delivering them the next day. -

Mumbai Residential June 2019 Marketbeats

MUMBAI RESIDENTIAL JUNE 2019 MARKETBEATS 2.5% 62% 27% GROWTH IN UNIT SHARE OF MID SHARE OF THANE SUB_MARKET L A U N C H E S (Q- o - Q) SEGMENT IN Q2 2019 IN LAUNCHES (Q2 2019) HIGHLIGHTS RENTAL VALUES AS OF Q2 2019* Average Quoted Rent QoQ YoY Short term Submarket New launches see marginal increase (INR/Month) Change (%) Change (%) outlook New unit launches have now grown for the third consecutive quarter, with 15,994 units High-end segment launched in Q2 2019, marking a 2.5% q-o-q increase. Thane and the Extended Eastern South 60,000 – 700,000 0% 0% South Central 60,000 - 550,000 0% 0% and Western Suburbs submarkets were the biggest contributors, accounting for around Eastern 25,000 – 400,000 0% 0% Suburbs 58% share in the overall launches. Eastern Suburbs also accounted for a notable 17% Western 50,000 – 800,000 0% 0% share of total quarterly launches. Prominent developers active during the quarter with new Suburbs-Prime Mid segment project launches included Poddar Housing, Kalpataru Group, Siddha Group and Runwal Eastern 18,000 – 70,000 0% 0% Suburbs Developers. Going forward, we expect the suburban and peripheral locations to account for Western 20,000 – 80,000 0% 0% a major share of new launch activity in the near future. Suburbs Thane 14,000 – 28,000 0% 0% Mid segment dominates new launches Navi Mumbai 10,000 – 50,000 0% 0% The mid segment continues to be the focus with a 62% share of the total unit launches during the quarter; translating to a q-o-q rise of 15% in absolute terms. -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1858 , 16/07/2018 Class 35 1818448 15

Trade Marks Journal No: 1858 , 16/07/2018 Class 35 1818448 15/05/2009 BALBIR KUMAR YUVRAJ ARORA ABHISHEK ARORA trading as ;OCTAVE APPARELS G. T. ROAD (WEST), NEAR JALANDHAR BYE-PASS CHOWK, LUDHIANA-141008 (PUNJAB). MANUFACTURERS AND MERCHANT Address for service in India/Agents address: PURI TRADE MARK CO. "BRAND HOUSE",54-55, SUPER CYCLE MARKET, OPP. KWALITY KANDA, GILL ROAD, LUDHIANA-141003 (PUNJAB). Used Since :29/03/1990 DELHI 55, TRADING, WHOLESALE, RETAIL, IMPORT, EXPORT, MARKETING, DISTRIBUTION, RETAIL OUTLETS AND BUSINESS MANAGEMENT SERVICES RELATING TO ALL KINDS OF PERFUMERY & DEODORANTS (EXCEPT COSMETIC PRODUCTS). SUNGLASSES, OPTICAL APPARATUS & INSTRUMENTS, LEATHER BAGS AND LUGGAGE, LEATHER ACCESSORIES, LEATHER WALLET, LEATHER BELTS, LEATHER AND IMITATIONS OF LEATHER AND GOODS MADE OF THESE MATERIALS NOT INCLUDED IN OTHER CLASSES, TRAVELING BAGS (EXCEPT LEATHER JACKETS, LEATHER CAPS, LADIES LEATHER BAGS, UMBRELLAS AND WALKING STICKS). YARNS & THREADS, TEXTILE AND TEXTILE PIECE GOODS NOT INCLUDED IN OTHER CLASSES, BED AND TABLE COVERS, TOWELS, BLANKETS (EXCEPT SHAWLS, LOHIS, STOLES AND MUFFLERS), ALL KINDS OF CIRCULAR KNITTED HALF SLEEVES T-SHIRTS, CAPRIS, WOVEN LOWERS, TROUSERS, JEANS, SHORTS, SWEAT SHIRTS, JOGGING SUITS, KNITTED FABRIC LOWERS, PACK OF THREE T-SHIRTS (ROUND NECK HALF SLEEVES T-SHIRTS MADE FROM CIRCULAR MACHINE KNITTED SINGLE JERSEY PLAIN FABRIC), BOYS AND BOY"S KIDSWEARS, GENTS UNDERGARMENTS, SWIMWEAR, NECK TIES (EXCEPTFLAT KNITTED HALF SLEEVES T-SHIRTS, SWEATERS OF ALL KINDS, JACKETS, HALF SLEEVES WOVEN SHIRTS, FULL SLEEVES WOVEN SHIRTS, FULL SLEEVES T-SHIRTS, GIRLSWEARS, GIRL"S KIDSWEAR, MEN"S BRIEFS, CAPS, LADIES UNDERGARMENTS, SOCKS, FOOTWEARS AND PACK OF ONE ROUND NECK HALF SLEEVES T-SHIRTS MADE FROM CIRCULAR MACHINE KNITTED SINGLE JERSEY PLAIN FABRIC), MEN"S SPORTING ARTICLES, MEN"S SPORTS WEARS (EXCEPTGIRL"S SPORTING ARTICLES ANDGIRVS SPORTS WEARS) FOR SALE IN JNDIA &FOR EXPORT. -

Colonial Indian Architecture:A Historical Overview

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology Issn No : 1006-7930 Colonial Indian Architecture:A Historical Overview Debobrat Doley Research Scholar, Dept of History Dibrugarh University Abstract: The British era is a part of the subcontinent’s long history and their influence is and will be seen on many societal, cultural and structural aspects. India as a nation has always been warmly and enthusiastically acceptable of other cultures and ideas and this is also another reason why many changes and features during the colonial rule have not been discarded or shunned away on the pretense of false pride or nationalism. As with the Mughals, under European colonial rule, architecture became an emblem of power, designed to endorse the occupying power. Numerous European countries invaded India and created architectural styles reflective of their ancestral and adopted homes. The European colonizers created architecture that symbolized their mission of conquest, dedicated to the state or religion. The British, French, Dutch and the Portuguese were the main European powers that colonized parts of India.So the paper therefore aims to highlight the growth and development Colonial Indian Architecture with historical perspective. Keywords: Architecture, British, Colony, European, Modernism, India etc. INTRODUCTION: India has a long history of being ruled by different empires, however, the British rule stands out for more than one reason. The British governed over the subcontinent for more than three hundred years. Their rule eventually ended with the Indian Independence in 1947, but the impact that the British Raj left over the country is in many ways still hard to shake off. -

The Victorian and Art Deco Ensemble of Mumbai (India) No 1480

Consultations ICOMOS consulted its International Scientific Committees The Victorian and Art Deco Ensemble on Shared Built Heritage, on 20th Century Heritage, on of Mumbai Historic Towns and Villages, and several independent experts. (India) No 1480 Technical Evaluation Mission A technical evaluation mission from ICOMOS visited the nominated property from 6 to 11 September 2017. Additional information received by ICOMOS Official name as proposed by the State Party A letter was sent from ICOMOS to the State Party on The Victorian and Art Deco Ensemble of Mumbai 1 August 2017 requesting updated information on the nomination dossier, particularly on issues of protection Location management and conservation. Also, additional Mumbai, Maharashtra State information was requested regarding the boundaries of India the property and the buffer zone, justification for inscription, the resolution of the submitted maps, and Brief description questions about management and protection. A The demolition of the fortifications of Bombay in the 1860s response with additional information was received by marked the transformation of the city from a fortified ICOMOS from the State Party on 5 September 2017. outpost into a world class commercial centre and made available land for development. A group of public An Interim Report was sent to the State Party on buildings was built in the Victorian Gothic style and the 22 December 2017 and the State Party provided open green space of the Oval Maidan was created. The ICOMOS with additional information on 13 February th Backbay Reclamation Scheme in the early 20 century 2018. The information submitted has been incorporated offered a new opportunity for Bombay to expand to the in the relevant sections of this report. -

NOBLE PLUS Sr No

NOBLE PLUS Sr No. Br Location Shop Name Address Contact number Indian Oil Petrol Pump, Below Airport Metro Station, Andheri - Kurla Road, Marol, Andheri 1 MAROL, ANDHERI EAST Noble Plus (E), Mumbai - 400059 28349999, 28391199 Shop No. 1, Joanna Co-Operative Housing Society, Manuel Gonsalves Road, Bandra West, 2 M. G. ROAD, BANDRA WEST Noble Plus Mumbai, Maharashtra 400050 26431129, 9029069559 7-A, Seven Star Society, 33rd Road, Bandra West, Landmark : Mini Punjab Restaurant, Mumbai, 4 33RD, BANDRA WEST Noble Plus Maharashtra 400050 26493333, 9029069590 DIAMOND GARDEN, Bahari Auto Compound, S.T. Road, Opposite 5 CHEMBUR EAST Noble Plus Diamond Garden, Chembur (E), Mumbai-71 25202520, 9029069565 #6 , Maker Arcade ,Near World Trade Center, 6 CUFFE PARADE Noble Plus Cuffe Parade, Mumbai, 400005 22168888, 7718806670 Rustomjee Ozone Bldg, Goregaon - Mulund Link MULUND LINK ROAD, Rd, Sunder Nagar, Goregaon West, Mumbai, 7 GOREGAON WEST Noble Plus Maharashtra 400064 28710057, 9029069567 Ground Floor, Indian Oil Petrol Pump, Opp. Majas Bus Depot, JVLR Jogeshwari East Mumbai 8 JVLR, JOGESHWARI EAST Noble Plus 400060 28268888 #55, Krishna Vasant Sagar, Thakur village, Near THAKUR VILLAGE, Thakur Cinema, Kandivali East, Mumbai, 9 KANDIVALI EAST Noble Plus Maharashtra 400101 28855560, 9029069566 DAHANUKARWADI, 1,2 & 3, Kamalvan, Junction of Link Road, M.G. 10 KANDIVALI WEST Noble Plus Road, Kandivali (W), Mumbai -400067 28682349, 9029069568 #2,Tanna Kutir,17th Roaad,Next to Neelam 11 17TH ROAD, KHAR WEST Noble Plus Foodland,, 17th Rd, Khar West, Mumbai-52. 26047777, 8433915319 #2,Mahesh Society, 3rd TPS, 5th Road, Khar 12 5TH ROAD, KHAR WEST Noble Plus West, Mumbai, Maharashtra 400052 26492222, 7718805146 VEER SAVARKAR MARG, 3, West wind, Veer Savarkar Marg, Mahim West, 13 MAHIM Noble Plus Mumbai, Maharashtra 400016 24444141, 7718806673 Heera panna mall, Powai, Mumbai, Maharashtra 14 A. -

CRAMPED for ROOM Mumbai’S Land Woes

CRAMPED FOR ROOM Mumbai’s land woes A PICTURE OF CONGESTION I n T h i s I s s u e The Brabourne Stadium, and in the background the Ambassador About a City Hotel, seen from atop the Hilton 2 Towers at Nariman Point. The story of Mumbai, its journey from seven sparsely inhabited islands to a thriving urban metropolis home to 14 million people, traced over a thousand years. Land Reclamation – Modes & Methods 12 A description of the various reclamation techniques COVER PAGE currently in use. Land Mafia In the absence of open maidans 16 in which to play, gully cricket Why land in Mumbai is more expensive than anywhere SUMAN SAURABH seems to have become Mumbai’s in the world. favourite sport. The Way Out 20 Where Mumbai is headed, a pointer to the future. PHOTOGRAPHS BY ARTICLES AND DESIGN BY AKSHAY VIJ THE GATEWAY OF INDIA, AND IN THE BACKGROUND BOMBAY PORT. About a City THE STORY OF MUMBAI Seven islands. Septuplets - seven unborn babies, waddling in a womb. A womb that we know more ordinarily as the Arabian Sea. Tied by a thin vestige of earth and rock – an umbilical cord of sorts – to the motherland. A kind mother. A cruel mother. A mother that has indulged as much as it has denied. A mother that has typically left the identity of the father in doubt. Like a whore. To speak of fathers who have fought for the right to sire: with each new pretender has come a new name. The babies have juggled many monikers, reflected in the schizophrenia the city seems to suffer from. -

Runwal the Reserve

https://www.propertywala.com/runwal-the-reserve-mumbai Runwal The Reserve - Worli, Mumbai 3 & 4 BHK apartments available at Runwals The Reserve Runwal The Reserve presented by Runwal Group with 3 & 4 BHK apartments available at Worli, Mumbai Project ID : J811900566 Builder: Runwal Group Location: Runwal The Reserve, Worli, Mumbai - 400018 (Maharashtra) Completion Date: Feb, 2016 Status: Started Description Runwal The Reserve is one of the residential developments by Runwal Group. It is located at Worli, Mumbai, Maharashtra. It offers skillfully designed 3 BHK and 4 BHK flats. The project is well equipped with all the amenities to facilitate the needs of the residents. Round the clock security is also available. Project Details Total area: 5 Acres Number of Blocks: 3 Number of Floors: G+25 Number of Units: 81 Amenities Hospital Community Center School Swimming Pool Multi Specialty Gym Yoga Center Club Park The Runwal group was established in 1978. The Runwal group is one of the leading players in several segments including construction and retail. The also make sure that great quality work, professionalism and customer satisfaction are some of the many things the group represents. In a society where good housing remains a basic necessity, Runwal is committed to making simple and elegant homes at a reasonably good speed. Features Luxury Features Security Features Power Back-up Centrally Air Conditioned Lifts Security Guards Electronic Security RO System High Speed Internet Wi-Fi Intercom Facility Fire Alarm Lot Features Lot Private Terrace -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

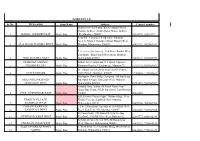

Hotel List 19.03.21.Xlsx

QUARANTINE FACILITIES AVAILABLE AS BELOW (Rate inclusive of Taxes and Three Meals) NO. DISTRICT CATEGORY NAME OF THE HOTEL ADDRESS SINGLE DOUBLE VACANCY POC CONTACT NUMBER FIVE STAR HOTELS 1 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Hilton Andheri (East) 3449 3949 171 Sandesh 9833741347 2 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star ITC Maratha Andheri (East) 3449 3949 70 Udey Schinde 9819515158 3 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Hyatt Regency Andheri (East) 3499 3999 300 Prashant Khanna 9920258787 4 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Waterstones Hotel Andheri (East) 3500 4000 25 Hanosh 9867505283 5 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Renaissance Powai 3600 3600 180 Duty Manager 9930863463 6 Mumbai Surburban 5 Star The Orchid Vile Parle (East) 3699 4250 92 Sunita 9169166789 7 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Sun-N- Sand Juhu, Mumbai 3700 4200 50 Kumar 9930220932 8 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star The Lalit Andheri (East) 3750 4000 156 Vaibhav 9987603147 9 Mumbai Surburban 5 Star The Park Mumbai Juhu Juhu tara Rd. Juhu 3800 4300 26 Rushikesh Kakad 8976352959 10 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Sofitel Mumbai BKC BKC 3899 4299 256 Nithin 9167391122 11 Mumbai City 5 Star ITC Grand Central Parel 3900 4400 70 Udey Schinde 9819515158 12 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Svenska Design Hotels SAB TV Rd. Andheri West 3999 4499 20 Sandesh More 9167707031 13 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Meluha The Fern Hiranandani Powai 4000 5000 70 Duty Manager 9664413290 14 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Grand Hyatt Santacruz East 4000 4500 120 Sonale 8657443495 15 Mumbai City 5 Star Taj Mahal Palace (Tower) Colaba 4000 4500 81 Shaheen 9769863430 16 Mumbai City 5 Star President, Mumbai Colaba -

Answered On:31.07.2000 Buildings for Post Offices Baliram

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA COMMUNICATIONS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:1258 ANSWERED ON:31.07.2000 BUILDINGS FOR POST OFFICES BALIRAM Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS be pleased to state: (a) the details of post offices functioning in rented buildings particularly in Azamgarh and Mau districts of U.P. and Mumbai in Maharashtra, district-wise; (b) the amount paid by the Government as rent for these buildings during 1999-2000; (c) whether the Government propose to construct departmental buildings for the post offices at those places; (d) if so, the details thereof, district-wise; and (e) if not, the reasons therefor? Answer MINISTER OF STATE FOR COMMUNICATIONS (SHRI TAPAN SIKDAR): (a) There are a total of 2599 post offices functioning in rented buildings in U.P. and 228 post offices functioning in rented buildings in Mumbai city. Details of the post offices functioning in rented buildings particularly in Azamgarh and Mau district of U.P. and Mumbai in Maharashtra is given district wise at Annexure `A`. (b) The amount paid by the Government as rent for these rented buildings is given at Annexure `B`. (c) There is no immediate proposal for construction of departmental buildings at place mentioned in (a) above. (d)&(e) No reply called for in view of (c) above. STATEMENT IN RESPECT OF PART (a) & (b) OF THE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 1258 FOR 31ST JULY, 2000 REGARDING BUILDINGS FOR POST OFFICES. ANNEXURE `A` (a) The details of post offices functioning in Azamgarh districts, district wise is as follows: Ahraula, Ambari, Atraulia, Azamgarh -

Sample Product Assessment and Urban Design Guidelines Study

XYZ developer, August, 201X Forward Liases Foras was approached by SD Corporation to conduct Product Viability Study and Design Brief Development that can help them take a decision on future development plan for their XYZ Redevelopment Project located in Tardeo in Mumbai, Maharashtra. While, there are many ways to arrive at the recommendations related to product, price and phasing, we have considered rationales that according to urban economics are most crucial for success of any location. All the recommendations and suggestions mentioned in the report are directly or indirectly governed by scientifically laid down theories and methodologies of Urban Economics. We hope the report will be helpful to SD Corporation to envisage the project and its future market outlook. Disclaimer The information provided in this report is based on the data collected by Liases Foras. Liases Foras has taken due care in the collection of the data. However, Liases Foras does not warranty the correctness of the information provided in this report. The report is available only on "as is" basis and without any warranties express or implied. Liases Foras disclaims all warranties including the implied warranty of merchantability and fitness for any purpose. Without prejudice to the above, Liases Foras will not be liable for any damages of any kind arising from the use of this report, including, but not limited to direct, indirect, incidental, punitive, special, consequential and/ or exemplary damages including but not limited to, damages for loss of profit goodwill resulting from: The incorrectness and/or inaccuracy of the information available on or through the Site Any action taken, proceeding initiated, transaction entered into on the basis of the information available in this report Terms of usage, Except as expressly permitted below, users of this report should not copy, modify, alter, reverse engineer, disassemble, sell, transfer, rent, license, publish, distribute, disseminate or otherwise allow access to all or any of the Information.