Media on Migrants: Report from the Field-I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perils of Women Trafficking: a Case Study of Joynagar, Kultali Administrative Blocks, Sundarban, India

International Journal of Education, Culture and Society 2017; 2(2): 61-68 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijecs doi: 10.11648/j.ijecs.20170202.13 Perils of Women Trafficking: A Case Study of Joynagar, Kultali Administrative Blocks, Sundarban, India Karabi Das Department of Geography, University of Calcutta, Kolkata, India Email address: [email protected] To cite this article: Karabi Das. Perils of Women Trafficking: A Case Study of Joynagar, Kultali Administrative Blocks, Sundarban, India. International Journal of Education, Culture and Society. Vol. 2, No. 2, 2017, pp. 61-68. doi: 10.11648/j.ijecs.20170202.13 Received: February 25, 2017; Accepted: March 13, 2017; Published: March 28, 2017 Abstract: The Indian Sundarban, comprising of 19 community development blocks (6 in North 24 Parganas and 13 in South 24 Parganas) is physiographically a deltaic plain, having an intricate network of creeks and is ravaged by natural hazards like Tropical cyclones. The inhabitants of Sundarban are primarily involved in agriculture (monocropping due to increased salinity), aquaculture and collection of non timber forest products and thus do not enjoy adequate income. An ill effect of globalization, trafficking means the trade of humans for the purpose of sexual slavery, forced labor or commercial sexual exploitation of the victim. It is now dominated by organized traffickers who lure young girls by making fake promises of love, marriage and lucrative job offers. Kultali and Joynagar of Indian Sundarban are highly vulnerable to hazards due to their close proximity to river Matla to the east and Bay of Bengal to the south. For this paper, data of women trafficking was collected from police department. -

Posting of Ias Officers As on 12.04.2021 1

POSTING OF IAS OFFICERS AS ON 12.04.2021 No. Year Name Designation 1. 1983 Sh. Amitabha Mukherjee On Foreign Deputation ( Applied for VRS) 2. 1985 Sh. Sanjeev Chopra Director, Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration (LBSNAA) 3. 1985 Sh. Pawan Agarwal Chief Executive Officer, Food Safety & Standards Authority of India 4. 1986 Dr. R.S. Shukla Secretary, Ministry of Parlamentary Affairs, Govt. of India 5. 1986 Sh. Arun Mishra Regional Director, Asia-Pacific Region, International Civil (DoB : 26/06/1962) Aviation Organisation [Applied for VRS] 6. 1987 Sh. Talleen Kumar Chief Executive Officer, Government e-Marketplace Special Purpose Vehicle (GeM SPV) in the rank of Additional Secretary, Government of India 7. 1987 Sh. Alapan Bandyopadhyay Chief Secretary, Government of West Bengal 8. 1987 Sh. Naveen Prakash Additional Chief Secretary, Irrigation & Waterways Deptt with additional charge of Public Works Department 9. 1987 Sh. Sunil Kumar Gupta Additional Chief Secretary to Hon’ble Gorvernor of West Bengal 10. 1988 Sh. Indevar Pandey Special Secretary, Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region, Govt of India 11. 1988 Sh. H.K. Dwivedi Additional Chief Secretary, Home and Hill Affairs Department with additional charge of Parliamentary Affairs Department and Department of Planning & Statistics and Deptt of Programme Monitoring 12. 1988 Sh. M.V. Rao Additional Chief Secretary, P&RD Department with additional charge of Additional Chief Secretary, Cooperation Department 13. 1988 Sh. S. Suresh Kumar Additional Chief Secretary, Power Department 14. 1989 Sh. S. Kishore Additional Secretary, Department of Commerce, M/o Commerce & Industry, Govt. of India 15. 1989 Sh. Chandan Sinha Director General, National Archives of India, M/o Culture 16. -

District Sl No Name Post Present Place of Posting S 24 Pgs 1 TANIA

District Sl No Name Post Present Place of Posting PADMERHAT RURAL S 24 Pgs 1 TANIA SARKAR GDMO HOSPITAL S 24 Pgs 2 DR KIRITI ROY GDMO HARIHARPUR PHC S 24 Pgs 3 Dr. Monica Chattrejee, GDMO Kalikapur PHC S 24 Pgs 4 Dr. Debasis Chakraborty, GDMO Sonarpur RH S 24 Pgs 5 Dr. Tusar Kanti Ghosh, GDMO Fartabad PHC S 24 Pgs 6 Dr. Iman Bhakta GDMO Kalikapur PHC Momrejgarh PHC, Under S 24 Pgs 7 Dr. Uday Sankar Koyal GDMO Padmerhat RH, Joynagar - I Block S 24 Pgs 8 Dr. Dipak Kumar Ray GDMO Nolgara PHC S 24 Pgs 9 Dr. Basudeb Kar GDMO Jaynagar R.H. S 24 Pgs 10 Dr. Amitava Chowdhury GDMO Jaynagar R.H. Dr. Sambit Kumar S 24 Pgs 11 GDMO Jaynagar R.H. Mukharjee Nalmuri BPHC,Bhnagore S 24 Pgs 12 Dr. Snehadri Nayek GDMO I Block,S 24 Pgs Jirangacha S 24 Pgs 13 Dr. Shyama pada Banarjee GDMO BPHC(bhangar-II Block) Jirangacha S 24 Pgs 14 Dr. Himadri sekhar Mondal GDMO BPHC(bhangar-II Block) S 24 Pgs 15 Dr. Tarek Anowar Sardar GDMO Basanti BPHC S 24 Pgs 16 Debdeep Ghosh GDMO Basanti BPHC S 24 Pgs 17 Dr.Nitya Ranjan Gayen GDMO Jharkhali PHC S 24 Pgs 18 GDMO SK NAWAZUR RAHAMAN GHUTARI SARIFF PHC S 24 Pgs 19 GDMO DR. MANNAN ZINNATH GHUTARI SARIFF PHC S 24 Pgs 20 Dr.Manna Mondal GDMO Gosaba S 24 Pgs 21 Dr. Aminul Islam Laskar GDMO Matherdighi BPHC S 24 Pgs 22 Dr. Debabrata Biswas GDMO Kuchitalahat PHC S 24 Pgs 23 Dr. -

(F) Persons Missing

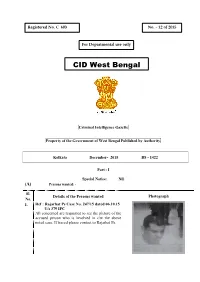

Registered No. C_603 No. – 12 of 2015 For Departmental use only CID West Bengal Criminal Intelligence Gazette Property of the Government of West Bengal Published by Authority. Kolkata December- 2015 BS - 1422 Part - I Special Notice: Nil. (A) Persons wanted: - Sl. Details of the Persons wanted Photograph No. 1. Ref : Rajarhat Ps Case No. 247/15 dated 06.10.15 U/s 379 IPC All concerned are requested to see the picture of the accused person who is involved in c/w the above noted case. If traced please contact to Rajarhat Ps. - 2 - 2. Ref : DumDum Ps Case No- 979/14 dated- 13/11/2014 U/s 420/406/506 IPC and adding section U/s 467/468/471 IPC And Ref : Khardah Ps Case No. 728/14 dated- 5.08.14 U/s 417/419/420/465/467/468/471 IPC The side pasted photos of two accused persons were collected from UCO Bank, Dum Dum Cantonment Branch, North 24 Parganas. They were involved in Bank fraud cases sevarel time. They have withdrawn cash of Rs. 2,75,500/- and 15,85,000/- in total Rs. 18,60,500/- from A/C No. 0733100005033 of the said Bank. All concerned are requested, if traced the above 1. noted accused persons contact to SS (HQ) CID, West Bengal, Phone No. 033-24506100/6174 and DDI Barackpore, Phone No. 033-2594-7174. Full particular of the accused persons:- 1. Dharmendra Yadav S/0 Shyam Charan Yadav of Garugarden Road, Provash Nagar, Dhubia Para, Ps- Srerampore, Dist- Hooghly Age- 25/26 years, Height- 5’-4” (approx), Build- Medium, Complexion- Sallow, Hair- Black 2. -

Howrah, West Bengal

Howrah, West Bengal 1 Contents Sl. No. Page No. 1. Foreword ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 2. District overview ……………………………………………………………………………… 5-16 3. Hazard , Vulnerability & Capacity Analysis a) Seasonality of identified hazards ………………………………………………… 18 b) Prevalent hazards ……………………………………………………………………….. 19-20 c) Vulnerability concerns towards flooding ……………………………………. 20-21 d) List of Vulnerable Areas (Village wise) from Flood ……………………… 22-24 e) Map showing Flood prone areas of Howrah District ……………………. 26 f) Inundation Map for the year 2017 ……………………………………………….. 27 4. Institutional Arrangements a) Departments, Div. Commissioner & District Administration ……….. 29-31 b) Important contacts of Sub-division ………………………………………………. 32 c) Contact nos. of Block Dev. Officers ………………………………………………… 33 d) Disaster Management Set up and contact nos. of divers ………………… 34 e) Police Officials- Howrah Commissionerate …………………………………… 35-36 f) Police Officials –Superintendent of Police, Howrah(Rural) ………… 36-37 g) Contact nos. of M.L.As / M.P.s ………………………………………………………. 37 h) Contact nos. of office bearers of Howrah ZillapParishad ……………… 38 i) Contact nos. of State Level Nodal Officers …………………………………….. 38 j) Health & Family welfare ………………………………………………………………. 39-41 k) Agriculture …………………………………………………………………………………… 42 l) Irrigation-Control Room ………………………………………………………………. 43 5. Resource analysis a) Identification of Infrastructures on Highlands …………………………….. 45-46 b) Status report on Govt. aided Flood Shelters & Relief Godown………. 47 c) Map-showing Govt. aided Flood -

Inventory of Soil Resources of Howrah District, West Bengal State Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques

Inventory of Soil Resources of Howrah District, West Bengal State Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques ABSTRACT 1. Survey Area : Howrah District, West Bengal State 2. Geographical : 22°12′ N and 22°47′ N latitudes and between 88°37′ E Extent and 87°50′ E longitudes 3. Agro Climatic : Lower Gangetic Plain (Zone no. III as per planning Region commission) 4. Total area : 146701 ha. 5. Kind of Survey : Soil Resources Mapping using remote sensing techniques. 6. Base map : a) IRS – ID Geocoded Satellite Imagery (1: 50000 scale) b) SOI –toposheet (1:50000 scale) 7. Scale of Mapping : 1 : 50000 8. Period of Survey : 2013-14 9. Soil Series association mapped and their respective area Map Mapping Area S.NO. Symbol Uuit Soil Association Area (ha) (%) 1 1 ALb1a1 Sluria-Hoglar 15180 10.35 2 10 ALb2b1 Amta-Chinsura 1792 1.22 3 11 ALb1d1 Nampala-Khalna 2072 1.41 4 12 ALg3a1 Bagnan-Betai Amta 2084 1.42 5 13 ALe3a1 Goindpur-Betai Amta 3263 2.22 6 2 ALb1a2 Mansma-Dhaudhali 13023 8.88 7 3 ALb1a3 Chandpur-Khalna 15151 10.33 Khalna-Najekhan- 8 4 ALb1a4 Mansinghapur 17728 12.08 9 5 ALn2a1 Mainan-Kandulia-Haridhara 6852 4.67 10 6 ALb2a1 Uluberia-Dhaudhali 8347 5.69 11 7 ALb2a2 Udaynarayanpur-Shibanipur 28256 19.26 12 8 ALb2a3 Bansipur-Ichapur 3920 2.67 13 9 ALb2a4 Dhaudhali-Nuniadanga 777 0.53 14 HS Homestead 19481 13.28 15 River River 8382 5.71 16 Tank Tank 383 0.26 17 Water body WB 10 0.01 Grand Total 146701 100 10. -

South 24 Parganas Merit List

NATIONAL MEANS‐CUM ‐MERIT SCHOLARSHIP EXAMINATION,2020 PAGE NO.1/92 GOVT. OF WEST BENGAL DIRECTORATE OF SCHOOL EDUCATION SCHOOL DISTRICT AND NAME WISE MERIT LIST OF SELECTED CANDIDATES CLASS‐VIII NAME OF ADDRESS OF ADDRESS OF QUOTA UDISE NAME OF SCHOOL DISABILITY MAT SAT SLNO ROLL NO. THE THE THE GENDER CASTE TOTAL DISTRICT CODE THE SCHOOL DISTRICT STATUS MARKS MARKS CANDIDATE CANDIDATE SCHOOL SUNDARBAN ADARSHA 210,KAK KALINAGAR,H P VIDYAMANDIR, VILL- COASTAL , SOUTH SUNDARBAN ADARSHA VIDYANAGAR PO- SOUTH 24 1 123205316055 ABHIJIT DAS NADIA 19181704901 M SC NONE 35 37 72 TWENTY FOUR VIDYAMANDIR KAKDWIP PS- KAKDWIP PARGANAS PARGANAS 743347 DIST- SOUTH 24 PGS, PIN- 743347 MANASADWIP RAMKRISHNA MISSION SAGAR,JIBANTALA,SAGA MANASADWIP SOUTH 24 HIGH SCHOOL, VILL- SOUTH 24 2 123205314148 ABHIK KHATUA R , SOUTH TWENTY FOUR 19182708401 RAMKRISHNA MISSION M GENERAL NONE 69 60 129 PARGANAS PURUSOTTAMPUR, PO- PARGANAS PARGANAS 743373 HIGH SCHOOL MANASADWIP, PS- SAGAR, SOUTH 24 PGS, PIN-743390 SATGACHIA,NODAKHALI, BAWALI HIGH SCHOOL , NODAKHALI , SOUTH SOUTH 24 VILL-BAWALI,PS- SOUTH 24 3 123205301040 ABHRADIP MALIK 19180812501 BAWALI HIGH SCHOOL M GENERAL NONE 50 66 116 TWENTY FOUR PARGANAS NODAKHALI,DIST- S PARGANAS PARGANAS 743318 24PGS, PIN-743384 NEAR RASH KASHINAGAR HIGH MORE,UTTAR SCHOOL, VILL- GOPALNAGAR,PATHAR SOUTH 24 KASHINAGAR HIGH KRISHNANAGAR, PS - SOUTH 24 4 123205316192 ADITI DAS 19181711002 F GENERAL NONE 58 57 115 PRATIMA , SOUTH PARGANAS SCHOOL KAKDWIP, DIST - 24 PARGANAS TWENTY FOUR PARGANAS SOUTH, PIN- PARGANAS 743347 743347 MASZID -

Date Wise Details of Covid Vaccination Session Plan

Date wise details of Covid Vaccination session plan Name of the District: Darjeeling Dr Sanyukta Liu Name & Mobile no of the District Nodal Officer: Contact No of District Control Room: 8250237835 7001866136 Sl. Mobile No of CVC Adress of CVC site(name of hospital/ Type of vaccine to be used( Name of CVC Site Name of CVC Manager Remarks No Manager health centre, block/ ward/ village etc) Covishield/ Covaxine) 1 Darjeeling DH 1 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVAXIN 2 Darjeeling DH 2 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVISHIELD 3 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom COVISHIELD 4 Kurseong SDH 1 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVAXIN 5 Kurseong SDH 2 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVISHIELD 6 Siliguri DH1 Koushik Roy 9851235672 Siliguri DH COVAXIN 7 SiliguriDH 2 Koushik Roy 9851235672 SiliguriDH COVISHIELD 8 NBMCH 1 (PSM) Goutam Das 9679230501 NBMCH COVAXIN 9 NBCMCH 2 Goutam Das 9679230501 NBCMCH COVISHIELD 10 Matigara BPHC 1 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVAXIN 11 Matigara BPHC 2 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVISHIELD 12 Kharibari RH 1 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVAXIN 13 Kharibari RH 2 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVISHIELD 14 Naxalbari RH 1 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVAXIN 15 Naxalbari RH 2 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVISHIELD 16 Phansidewa RH 1 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVAXIN 17 Phansidewa RH 2 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVISHIELD 18 Matri Sadan Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 Matri Sadan COVISHIELD 19 SMC UPHC7 1 Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 SMC UPHC7 COVAXIN 20 SMC UPHC7 2 Dr. -

Environmental & Social Impact Assessment

ENVIRONMENTAL & SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT UNDER GROUND CABLING NETWORK FOR BARUIPUR TOWN UNDER WBEDGMP Document No: IISWBM/ESIA-WBSEDCL/2019-2020/002 (Version: 1.3) August 2020 ENVIRONMENTAL & SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR UNDER GROUND CABLING NETWORK OF BARUIPUR TOWN UNDER WBEDGMP WITH WORLD BANK FUND ASSISTANCE Document No: IISWBM/ESIA-WBSEDCL/2019-20/002 Version: 1.3 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION COMPANY LIMITED Vidyut Bhavan, Bidhan Nagar Kolkata – 700 091 Executed by Indian Institute of Social Welfare & Business Management, Kolkata – 700 073 August, 2020 CONTENTS ITEM PAGE NO LIST OF FIGURE LIST OF TABLE LIST OF ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i-xiv 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1-7 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Need of ESIA 1 1.3 Objectives of the Study 2 1.4 Scope of the Study 2 1.5 Engagement & Mobilization of Consultant for the Study 4 1.6 Structure of Report 5 2.0 PROJECT DETAILS 8-20 2.1 National & State Programs in Power Section 8 2.1.1 Country and Sector Issue 8 2.1.2 West Bengal Power Sector 8 2.2 Project Overview 10 2.3 Proposed Project Development Objectives and Benefits 11 2.4 Project Location & Consumer Profile 12 2.4.1 Location 12 2.4.2 Consumer Details 14 2.4.3 Annual Load Growth 14 2.5 Project Description and Key Performance Indicators 15 2.5.1 Implementing Agency 15 2.5.2 Co-Financing 15 2.5.3 Project Components 15 2.5.4 Key Performance Indicators 17 3.0 POLICY AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORK 21-29 3.1 Legal and Regulatory Framework 21 3.2 World Bank Environmental and Social Standards (ESS) 25 3.3 Environmental and Social -

Stratified Random Sampling - West Bengal (Code -35)

Download The Result Stratified Random Sampling - West Bengal (Code -35) Species Selected for Stratification = Cattle + Buffalo Number of Villages Having 500 + (Cattle + Buffalo) = 11580 Design Level Prevalence = 0.50 Cluster Level Prevalence = 0.03 Sensitivity of the test used = 0.95 Total No of Villages (Clusters) Selected = 160 Total No of Animals to be Sampled = 1120 Back to Calculation Number Cattle of units Buffalo Cattle DISTRICT_NAME BLOCK_CODE BLOCK_NAME VILLAGE_NAME Buffaloes Cattle + all to Proportion Proportion Buffalo sample 24 Paraganas North 418 Swarupnagar Nirman 0 712 712 1655 7 0 7 24 Paraganas North 13 Baduria Jangalpur 0 997 997 1697 7 0 7 24 Paraganas North 180 Hingalganj Samsernagar 0 1119 1119 4356 7 0 7 24 Paraganas North 47 Basirhat - Ii Srinagar 0 1208 1208 3582 7 0 7 24 Paraganas North 364 Rajarhat Ghuni (Ct) 0 1418 1418 2369 7 0 7 24 Paraganas North 35 Barasat - I Santoshpur 2 1548 1550 1571 7 0 7 Madhyamgram 24 Paraganas North 271 Madhyamgram 2235 553 2788 2791 7 6 1 (M) - Ward No.25 24 Paraganas North 418 Swarupnagar Banglani 0 3482 3482 6275 7 0 7 24 Paraganas South 262 Kultali Mandalerlat 0 778 778 1745 7 0 7 24 Paraganas South 272 Magrahat - I Iyarpur 0 1003 1003 2041 7 0 7 24 Paraganas South 199 Jaynagar - Ii Jautia 4 1187 1191 2086 7 0 7 24 Paraganas South 81 Canning - I Kumarsa Chak 0 1301 1301 3396 7 0 7 24 Paraganas South 44 Basanti Kumarkhali 25 1498 1523 3342 7 0 7 24 Paraganas South 43 Baruipur Nabagram 0 1958 1958 3216 7 0 7 Rajnagar 24 Paraganas South 318 Namkhana 0 3142 3142 5175 7 0 7 Srinathgram -

Nutrient Index of Available S in Soils of Howrah and South Dinajpur Districts of West Bengal, India

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2019) 8(4): 1024-1032 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 8 Number 04 (2019) Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2019.804.119 Nutrient Index of Available S in Soils of Howrah and South Dinajpur Districts of West Bengal, India Rahul Kumar1*, Gora Chand Hazra1, Ruma Das2, Shyam Prasad Majumder1 and Amal Chandra Das1 1Division of Agricultural Chemistry and Soil Science, Bidhan Chandra Krishi Viswavidyalaya, Mohanpur, Nadia, West Bengal, India 2Division of Soil Science and Agricultural Chemistry, ICAR-IARI Pusa Campus, New Delhi, India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT K e yw or ds Nutrient index of available S in soils of two districts, namely, Howrah and South Dinajpur of West Bengal falling in the soil order Inceptisols collecting 237 soil samples from Nutrient Index, Howrah and 256 soil samples from South Dinajpur district. Soil samples were collected Howrah, South according to grid sampling pattern maintaining approximately 4.0 km grid for Howrah and Dinajpur, Fertility Status, Soil 3.7 km grid for South Dinajpur district using global positioning system (GARMIN GPS properties, Version etrex) covering 13 blocks of Howrah and 8 blocks of South Dinajpur district. Soil Inceptisols pH of the Howrah and South Dinajpur district ranged from 3.0to 8.30 with a mean value of 5.75 and 3.7 to 7.0 with a mean value of 5.21.The organic carbon content in soils of Article Info Howrah and South Dinajpur district ranged from 0.18 to 1.21% with a mean value of Accepted: 0.55% and 0.37 to 1.32% with a mean value of 0.84%. -

PRESS NOTE Inauguration of Newly Constructed Baruipur Bus Terminus

PRESS NOTE Inauguration of newly constructed Baruipur Bus Terminus by Shri Biman Bandyopadhyay, Hon’ble Speaker, West Bengal Legislative Assembly and Shri Suvendu Adhikari Hon’ble Minister-in-Charge, Transport & Environment Department, Govt. of West Bengal is held on 2nd March, 2019 at Baruipur Bus Terminus. Shri B. P. Gopalika, I.A.S., Principal Secretary, West Bengal Transport Department & Narayan Swaroop Nigam, I.A.S., Secretary, West Bengal Transport Department & Managing Director, West Bengal Transport Corporation was present along with other dignitaries. At Present there are 7 bus routes operated by the West Bengal Transport Corporation. These buses were earlier parked in the road side which caused different problems for operation of the buses. Considering the about difficulties and for better service in the future the above terminus have been constructed. To ensure the safety of the passengers the following bus routes will be shifted in the newly built Modern Bus Terminus for daily operation after inauguration. Sl.No. Route No of Route Details No. Buses 1. AC-14 2 Baruipur – Karunamoyee –Via- Kamalgazi – EM Bye Pass 2. C-26 12 Baruipur – Howrah –Via- - Kamalgazi – Science City- Esplanade 3. C-46 1 Baruipur – Nabanna– via- Suryapur-Bansundaria-Dhamua- Sirakal-Amtala-Behala 4. C-48 2 Baruipur – Dakshineswar – Via- Champahati – New Garia 5. C-49 2 Baruipur – Nabanna– Via- Champahati – New Garia 6. ST-12 2 Baruipur – Sapoorji Housing –Via- Kamalgazi-EM Bye Pass—New Town – Unitec 7. S-15G 2 Baruipur – Dakshineswar –via- Garia– Dharmatala – Shyambazar 8. Digha 1 (AC) 9 Digha 1 (non AC) For Construction of the New Bus Terminus 1.64 acre land was handed over to the Transport Department, Govt.