The Impact of Interactive Violence on Children Hearing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Annual Taxpayer Location Address List 2014

Annual Taxpayer Location Address List 2014 ILLINOIS BUSINESS TAX NUMBER SEQUENCE NUMBER TYPE OF FILER 4139-6499 0 CL 4152-9510 0 CL 4148-4207 0 CL 4044-1474 0 CL 0196-7053 0 CL 2241-7494 1 CL 4149-4229 0 CL 3904-2121 0 CL 3041-2331 0 CL Page 1 of 3815 09/27/2021 Annual Taxpayer Location Address List 2014 SIC DBA NAME OWNING ENTITY 5431 JACKIE BURNS 5947 KENSON ORR 5999 SHANNON WYNN BITE A BILLION 5947 MADELINE RAMOS KAY-EMI BALLOON KEEPSAKES 2038 SCHWANS HOME SERVICE INC 5065 ECHOSPHERE LLC 5947 AFRICOBRA LLC 5999 CHASE EVENTS INC 5661 VICTOR GUTIERREZ Page 2 of 3815 09/27/2021 Annual Taxpayer Location Address List 2014 ADDRESS ADDRESS SECONDARY CITY PO BOX 25 MARSHALL PO BOX 6623 ENGLEWOOD 316 PINE ST SUMTER 3N265 WILSON ST ELMHURST 5233 W 29TH PL CICERO Page 3 of 3815 09/27/2021 Annual Taxpayer Location Address List 2014 Boundaries - Community STATE ZIP LOCATION ZIP Codes Areas MN 56258-0025 PO BOX 25 MARSHALL, MN 56258-0025 (44.44589741800007, - 95.78116775399997) CO 80155-6623 PO BOX 6623 ENGLEWOOD, CO 80155-6623 (39.592180549000034, - 104.87610010699996) SC 29150-3545 316 PINE ST SUMTER, SC 29150-3545 (33.93458485700006, - 80.34958253299999) IL 60126-1359 3N265 WILSON ST ELMHURST, IL 60126-1359 (41.92621464400003, - 87.93331031799994) IL 60804-3523 5233 W 29TH PL CICERO, IL 60804-3523 Page 4 of 3815 09/27/2021 Annual Taxpayer Location Address List 2014 Historical Zip Codes Census Tracts Wards Wards 2003- 2015 21432 20300 12955 15603 4458 Page 5 of 3815 09/27/2021 Annual Taxpayer Location Address List 2014 4144-6917 0 CL 4114-7601 0 CL 2258-3394 0 CL 2251-1423 0 CL 0354-2785 0 CL 4002-5845 0 CL Page 6 of 3815 09/27/2021 Annual Taxpayer Location Address List 2014 5999 JASCO INC 5651 CORTEZ BROADNAX 2449 THE LONGABERGER CO 7379 DUNN SOLUTIONS GROUP INC 2099 LANDSHIRE INC 1389 IPC (USA) INC. -

List of Certified Suppliers

LIST OF CERTIFIED SUPPLIERS BY TYPES OF PRODUCTS/SERVICES and a list of MINNESOTA AMERICAN INDIAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE CONTRACTOR MEMBERS Carpet & Floor Maintenance Service Company Product/Service Contact Dynamic Cleaning Services Complete janitorial and Willie Suttle 635 W. Central Avenue carpet cleaning St. Paul, MN 55104 PH: 651-221-9731 FAX: 651-293-1137 # of Employees: 7 Year Established: 1981 Major Customers: Justin Properties, Face to Face Health Counseling Contractors/Subcontractors Aeration Aeration equipment for Richard wastewater treatment plants, Ravendren American Aerators, Inc. lakes & river restoration and 398 129th Street NW aquaculture ponds. Monticello, MN 55362 PO Box 44161 Eden Prairie, MN 55344 PH: 612-873-6951 FAX: 612-873-6951 # of Employees: 5 Year Established: 1994 SIC Code: 3589 Major Customers: City of Eagan, Spurlock Adhesives, Inc. Construction Supply Material handling, equipment Jay Goodwin sales and service, JGC Equipment Company construction supply, 10005 Goodhue Street NE hospitality equipment Blaine, MN 55449 PH: 612-780-7901 FAX: 612-780-7967 # of Employees: 14 Year Established: 1991 SIC Code: 5098 Major Customers: Grand Casino Mille Lacs, Medtronic, Kraus Anderson Company Product/Service Contact Elevator Installation/Maintenance Professional Elevator Services, Inc. Elevator installation, repair, Kenneth Mason 400 E. Randolph, Suite 3124 maintenance, modernization, Chicago, IL 60601 custom cab interiors and PH: 312-431-0055 FAX: 312-321-9637 general contracting service # of Employees: 20 Year Established: 1990 SIC Code: 1796, 1791 Major Customers: Montgomery Kone, Turner Construction Floor Covering Benson Carpet, Inc. Carpet, vinyl flooring, vinyl Paul DeLao 1889 Buerkle Road tile, hardwood flooring, White Bear Lake, MN 55110 ceramic and installation of PH: 651-777-8496 FAX: 651-777-3699 such material # of Employees: 3 Year Established: 1975 SIC Code: 5700 Major Customers: Thor Construction, Construction 70, Inc., Sheehy Const. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games (Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack (TG16, Arcade) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1942 (Revision B) (Arcade) 12. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) (Arcade) 13. 1943: Kai (TG16) 14. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 15. 1944: The Loop Master (Arcade) 16. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 17. 19XX: The War Against Destiny (Arcade) 18. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge (Arcade) 19. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 20. 2020 Super Baseball (SNES, Arcade) 21. 21-Emon (TG16) 22. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 23. 3 Count Bout (Arcade) 24. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 25. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 26. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 27. -

EA Teams up with Legendary Development Studio Id Software for RAGE

EA Teams up With Legendary Development Studio id Software for RAGE EA Partners to Publish the Next Blockbuster From the Inventors of the First Person Shooter LOS ANGELES, Jul 14, 2008 (BUSINESS WIRE) -- Electronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ:ERTS) today announced that it has signed an agreement with id Software, award-winning creators of iconic gaming brands and industry defining innovations, to publish RAGE(TM), the studio's next blockbuster franchise. Built on id Software's newest game engine, id Tech5, RAGE is an all-new take on the first person shooter being developed for release on the PLAYSTATION(R)3 computer entertainment system, Xbox 360(TM) system from Microsoft, PC and Mac. "RAGE represents a new direction for our games," said Todd Hollenshead, CEO of id Software. "RAGE is a shooter unlike any other, developed on our cutting edge new technology, and built to the exacting standards id is famous for. We're excited to have the support of EA Partners to launch RAGE on the world." "The RAGE publishing deal is the epitome of EA Partners' mission: Provide the world's best developers with access to the world's best publishing resources," said David DeMartini, senior vice president and general manager of EA Partners. "The team at id Software is one of the best development studios in the world. We're excited to work with id Software to give RAGE a blockbuster launch on the global stage." Stay tuned for additional information about RAGE at QuakeCon 2008 in Dallas, Texas from July 31 to August 2nd. More information about QuakeCon is available at www.quakecon.org About id Software id - defined by Freud as the primal section of the human psyche; id Software, located in Mesquite, Texas, was founded in 1991. -

05-15-14 Karlsen Digra Proofread

Analysing the history of game controversies Faltin Karlsen Norwegian School of Information Technology Schweigaardsgate 14 N-0185 +47 90 73 70 88 [email protected] ABSTRACT The aim of this paper is to discuss some of the controversies that have surrounded digital games. Within media studies, such controversies are often referred to as moral panics or media panics. They are understood as cyclical events that arise when new media or media phenomena are introduced into society. The paper’s point of departure is the controversy that erupted after the launch of Death Race in 1976, which initiated the first world- spanning debate concerning digital games and violence. Similar debates followed the launch of games like Doom and Mortal Kombat. More recent controversies about game violence have erupted specifically in the wake of school shootings. My analysis shows that, while these debates certainly share similarities, they also undergo important transformations over time. Via a historical perspective, I will demonstrate the importance of these changes to our understanding of the status of digital games in society. Keywords moral panic, media panic, game violence, media regulation, media history INTRODUCTION The concept of media panic is often invoked when public controversies arise around digital games or other media. A media panic is a heated public debate that is most often ignited when a new medium enters society. Concern is usually expressed on behalf of children or youth, and the medium is described as seductive, psychologically harmful, or immoral (Drotner 1999). While media panics tend to revolve around new media, slightly older media, like newspapers and television, are where these concerns are expressed. -

The Rise of Nintendo and the Nintendo Entertainment System Conquers America

The Rise of Nintendo and the Nintendo Entertainment System Conquers America In order to expand the reach of Nintendo, company president Hiroshi Yamauchi had Masayuki Uemura design a home console Yamauchi wanted the console to be a year ahead of the competition in technology and cost a third of the price of the Epoch Cassette Vision Uemura’s original design came with a modem, keyboard, and disk drive, but these were removed to lower the cost The system was released as the Family Computer, or Famicom for short, and its controller was based on the Game & Watch version of Donkey Kong Yamauchi picked three of Shigeru Miyamoto’s games – Donkey Kong, Donkey Kong Jr., and Popeye to be launch titles for the Famicom Yamauchi’s goal was to make money not off of the console sales, but off of the game sales Within two months of its July 1983 release, the Famicom sold 500,000 units, with more than a million units sold by years end Nintendo couldn’t keep up with its quickly growing fan base, and Yamauchi’s solution was to allow other game publishers to make games for the Famicom Nintendo set up some rules about allowing others make games for the Famicom Nintendo wanted cash upfront to manufacture cartridges, a cut of the profits from sales, and the right to veto the release of any game, including all pornographic bishojo games Many publishers baulked at Nintendo’s demands, finding them to be too strict Hudson Soft, makers of Bomber Man, signed up and released Roadrunner, a remake of the American platformer Load Runner, which sold over a -

Regulating Violence in Video Games: Virtually Everything

Journal of the National Association of Administrative Law Judiciary Volume 31 Issue 1 Article 7 3-15-2011 Regulating Violence in Video Games: Virtually Everything Alan Wilcox Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/naalj Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Alan Wilcox, Regulating Violence in Video Games: Virtually Everything, 31 J. Nat’l Ass’n Admin. L. Judiciary Iss. 1 (2011) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/naalj/vol31/iss1/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the National Association of Administrative Law Judiciary by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Regulating Violence in Video Games: Virtually Everything By Alan Wilcox* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................. ....... 254 II. PAST AND CURRENT RESTRICTIONS ON VIOLENCE IN VIDEO GAMES ........................................... 256 A. The Origins of Video Game Regulation...............256 B. The ESRB ............................. ..... 263 III. RESTRICTIONS IMPOSED IN OTHER COUNTRIES . ............ 275 A. The European Union ............................... 276 1. PEGI.. ................................... 276 2. The United -

Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2008-03-28 Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship Bradley R. Clark Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Clark, Bradley R., "Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship" (2008). Theses and Dissertations. 1350. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/1350 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Using the ZMET Method 1 Running head: USING THE ZMET METHOD TO UNDERSTAND MEANINGS Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship Bradley R Clark A project submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Brigham Young University April 2008 Using the ZMET Method 2 Copyright © 2008 Bradley R Clark All Rights Reserved Using the ZMET Method 3 Using the ZMET Method 4 BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL of a project submitted by Bradley R Clark This project has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

Arcade Rewind 3500 Games List 190818.Xlsx

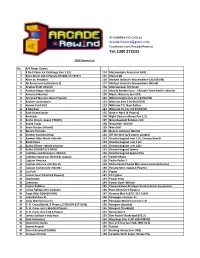

ArcadeRewind.com.au [email protected] Facebook.com/ArcadeRewind Tel: 1300 272233 3500 Games List No. 3/4 Player Games 1 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 114 Metamorphic Force (ver EAA) 2 Alien Storm (US,3 Players,FD1094 317-0147) 115 Mexico 86 3 Alien vs. Predator 116 Michael Jackson's Moonwalker (US,FD1094) 4 All American Football (rev E) 117 Michael Jackson's Moonwalker (World) 5 Arabian Fight (World) 118 Minesweeper (4-Player) 6 Arabian Magic <World> 119 Muscle Bomber Duo - Ultimate Team Battle <World> 7 Armored Warriors 120 Mystic Warriors (ver EAA) 8 Armored Warriors (Euro Phoenix) 121 NBA Hangtime (rev L1.1 04/16/96) 9 Asylum <prototype> 122 NBA Jam (rev 3.01 04/07/93) 10 Atomic Punk (US) 123 NBA Jam T.E. Nani Edition 11 B.Rap Boys 124 NBA Jam TE (rev 4.0 03/23/94) 12 Back Street Soccer 125 Neck-n-Neck (4 Players) 13 Barricade 126 Night Slashers (Korea Rev 1.3) 14 Battle Circuit <Japan 970319> 127 Ninja Baseball Batman <US> 15 Battle Toads 128 Ninja Kids <World> 16 Beast Busters (World) 129 Nitro Ball 17 Blazing Tornado 130 Numan Athletics (World) 18 Bomber Lord (bootleg) 131 Off the Wall (2/3-player upright) 19 Bomber Man World <World> 132 Oriental Legend <ver.112, Chinese Board> 20 Brute Force 133 Oriental Legend <ver.112> 21 Bucky O'Hare <World version> 134 Oriental Legend <ver.126> 22 Bullet (FD1094 317-0041) 135 Oriental Legend Special 23 Cadillacs and Dinosaurs <World> 136 Oriental Legend Special Plus 24 Cadillacs Kyouryuu-Shinseiki <Japan> 137 Paddle Mania 25 Captain America 138 Pasha Pasha 2 26 Captain America -

Gaming Scenarios: Making Sense of Diverging Developments

DOI:10.6531/JFS.2017.22(2).A15 ARTICLE .15 Gaming Scenarios: Making Sense of Diverging Developments Sascha Dannenberg Freie Universität Berlin Germany Nele Fischer Freie Universität Berlin Germany Abstract This article introduces Huizinga’s notion of the Homo Ludens as theoretical framework to gaming approaches in Futures Studies. This understanding of games as social functions, simultaneously representing reality and creating social structures, is then discussed in relation to scenario techniques. Finally, a scenario project from Berlin, Germa- ny is presented as case study, showing how gaming scenarios can engage participants in playfully thinking about and experimenting with futures. Keywords: Experiential foresight, Card game, Homo Ludens, Gaming, Scenario. Introduction Experiential Turn in Futures Studies What Futures Studies is (or should be) has been discussed along a divide between analytical and creative approaches right from the beginning (see e.g. Masini, 1993; Marien, 2002; Bell, 2003). Futures Studies would be understood either as science or as art, while many considered both approaches as being incompatible (see e.g. de Jouvenel, 1967; Bell 2003). However, in recent years the so-called experiential turn1 became prominent within Futures Studies. Experiential foresight combines analytical, creative and experimental approaches. It is based mostly on methods and techniques of interactive play (theatre, board games), experimental research (modeling, design), and different forms of immersive visualization (interactive videos, virtual reality) (Daheim, 2015). The development of experiential foresight can be seen within a context of changing demands on research in general and on Futures Studies in particular: For example, there is a rising emphasis on tangible outcomes as well as a stronger focus on motivation and realization of shared images of the future through stakeholder Journal of Futures Studies, December 2017, 22(2): 15–26 Journal of Futures Studies engagement (Daheim, 2015).