A Different Kind of Institute: the American Institute of Mathematics Allyn Jackson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I. Overview of Activities, April, 2005-March, 2006 …

MATHEMATICAL SCIENCES RESEARCH INSTITUTE ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2005-2006 I. Overview of Activities, April, 2005-March, 2006 …......……………………. 2 Innovations ………………………………………………………..... 2 Scientific Highlights …..…………………………………………… 4 MSRI Experiences ….……………………………………………… 6 II. Programs …………………………………………………………………….. 13 III. Workshops ……………………………………………………………………. 17 IV. Postdoctoral Fellows …………………………………………………………. 19 Papers by Postdoctoral Fellows …………………………………… 21 V. Mathematics Education and Awareness …...………………………………. 23 VI. Industrial Participation ...…………………………………………………… 26 VII. Future Programs …………………………………………………………….. 28 VIII. Collaborations ………………………………………………………………… 30 IX. Papers Reported by Members ………………………………………………. 35 X. Appendix - Final Reports ……………………………………………………. 45 Programs Workshops Summer Graduate Workshops MSRI Network Conferences MATHEMATICAL SCIENCES RESEARCH INSTITUTE ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2005-2006 I. Overview of Activities, April, 2005-March, 2006 This annual report covers MSRI projects and activities that have been concluded since the submission of the last report in May, 2005. This includes the Spring, 2005 semester programs, the 2005 summer graduate workshops, the Fall, 2005 programs and the January and February workshops of Spring, 2006. This report does not contain fiscal or demographic data. Those data will be submitted in the Fall, 2006 final report covering the completed fiscal 2006 year, based on audited financial reports. This report begins with a discussion of MSRI innovations undertaken this year, followed by highlights -

Richard Schoen – Mathematics

Rolf Schock Prizes 2017 Photo: Private Photo: Richard Schoen Richard Schoen – Mathematics The Rolf Schock Prize in Mathematics 2017 is awarded to Richard Schoen, University of California, Irvine and Stanford University, USA, “for groundbreaking work in differential geometry and geometric analysis including the proof of the Yamabe conjecture, the positive mass conjecture, and the differentiable sphere theorem”. Richard Schoen holds professorships at University of California, Irvine and Stanford University, and is one of three vice-presidents of the American Mathematical Society. Schoen works in the field of geometric analysis. He is in fact together with Shing-Tung Yau one of the founders of the subject. Geometric analysis can be described as the study of geometry using non-linear partial differential equations. The developments in and around this field has transformed large parts of mathematics in striking ways. Examples include, gauge theory in 4-manifold topology, Floer homology and Gromov-Witten theory, and Ricci-and mean curvature flows. From the very beginning Schoen has produced very strong results in the area. His work is characterized by powerful technical strength and a clear vision of geometric relevance, as demonstrated by him being involved in the early stages of areas that later witnessed breakthroughs. Examples are his work with Uhlenbeck related to gauge theory and his work with Simon and Yau, and with Yau on estimates for minimal surfaces. Schoen has also established a number of well-known and classical results including the following: • The positive mass conjecture in general relativity: the ADM mass, which measures the deviation of the metric tensor from the imposed flat metric at infinity is non-negative. -

Curriculum Vitae.Pdf

Lan-Hsuan Huang Department of Mathematics Phone: (860) 486-8390 University of Connecticut Fax: (860) 486-4238 Storrs, CT 06269 Email: [email protected] USA http://lhhuang.math.uconn.edu Research Geometric Analysis and General Relativity Employment University of Connecticut Professor 2020-present Associate Professor 2016-2020 Assistant Professor 2012-2016 Institute for Advanced Study Member (with the title of von Neumann fellow) 2018-2019 Columbia University Ritt Assistant Professor 2009-2012 Education Ph.D. Mathematics, Stanford University 2009 Advisor: Professor Richard Schoen B.S. Mathematics, National Taiwan University 2004 Grants • NSF DMS-2005588 (PI, $250,336) 2020-2023 & Honors • von Neumann Fellow, Institute for Advanced Study 2018-2019 • Simons Fellow in Mathematics, Simons Foundation ($122,378) 2018-2019 • NSF CAREER Award (PI, $400,648) 2015-2021 • NSF Grant DMS-1308837 (PI, $282,249) 2013-2016 • NSF Grant DMS-1005560 and DMS-1301645 (PI, $125,645) 2010-2013 Visiting • Erwin Schr¨odingerInternational Institute July 2017 Positions • National Taiwan University Summer 2016 • MSRI Research Member Fall 2013 • Max-Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics, Germany Fall 2010 • Institut Mittag-Leffler, Sweden Fall 2008 1 Journal 1. Equality in the spacetime positive mass theorem (with D. Lee), Commu- Publications nications in Mathematical Physics 376 (2020), no. 3, 2379{2407. 2. Mass rigidity for hyperbolic manifolds (with H. C. Jang and D. Martin), Communications in Mathematical Physics 376 (2020), no. 3, 2329- 2349. 3. Localized deformation for initial data sets with the dominant energy condi- tion (with J. Corvino), Calculus Variations and Partial Differential Equations (2020), no. 1, No. 42. 4. Existence of harmonic maps into CAT(1) spaces (with C. -

Stable Minimal Hypersurfaces in Four-Dimensions

STABLE MINIMAL HYPERSURFACES IN R4 OTIS CHODOSH AND CHAO LI Abstract. We prove that a complete, two-sided, stable minimal immersed hyper- surface in R4 is flat. 1. Introduction A complete, two-sided, immersed minimal hypersurface M n → Rn+1 is stable if 2 2 2 |AM | f ≤ |∇f| (1) ZM ZM ∞ for any f ∈ C0 (M). We prove here the following result. Theorem 1. A complete, connected, two-sided, stable minimal immersion M 3 → R4 is a flat R3 ⊂ R4. This resolves a well-known conjecture of Schoen (cf. [14, Conjecture 2.12]). The corresponding result for M 2 → R3 was proven by Fischer-Colbrie–Schoen, do Carmo– Peng, and Pogorelov [21, 18, 36] in 1979. Theorem 1 (and higher dimensional analogues) has been established under natural cubic volume growth assumptions by Schoen– Simon–Yau [37] (see also [45, 40]). Furthermore, in the special case that M n ⊂ Rn+1 is a minimal graph (implying (1) and volume growth bounds) flatness of M is known as the Bernstein problem, see [22, 17, 3, 45, 6]. Several authors have studied Theorem 1 under some extra hypothesis, see e.g., [41, 8, 5, 44, 11, 32, 30, 35, 48]. We also note here some recent papers [7, 19] concerning stability in related contexts. It is well-known (cf. [50, Lecture 3]) that a result along the lines of Theorem 1 yields curvature estimates for minimal hypersurfaces in R4. Theorem 2. There exists C < ∞ such that if M 3 → R4 is a two-sided, stable minimal arXiv:2108.11462v2 [math.DG] 2 Sep 2021 immersion, then |AM (p)|dM (p,∂M) ≤ C. -

A Representation Formula for the P-Energy of Metric Space Valued

A REPRESENTATION FORMULA FOR THE p-ENERGY OF METRIC SPACE VALUED SOBOLEV MAPS PHILIPPE LOGARITSCH AND EMANUELE SPADARO Abstract. We give an explicit representation formula for the p-energy of Sobolev maps with values in a metric space as defined by Korevaar and Schoen (Comm. Anal. Geom. 1 (1993), no. 3-4, 561–659). The formula is written in terms of the Lipschitz compositions introduced by Ambrosio (Ann. Scuola Norm. Sup. Pisa Cl. Sci. (4) 3 (1990), n. 17, 439–478), thus further relating the two different definitions considered in the literature. 0. Introduction In this short note we show an explicit representation formula for the p-energy of weakly differentiable maps with values in a separable complete metric space, thus giving a contribution to the equivalence between different theories considered in the literature. Since the early 90’s, weakly differentiable functions with values in singular spaces have been extensively studied in connection with several questions in mathematical physics and geometry (see, for instance, [1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22]). Among the different approaches which have been proposed, we recall here the ones by Korevaar and Schoen [15] and Jost [12] based on two different expressions of approximate energies; that by Ambrosio [1] and Reshetnyak [18] using the compositions with Lipschitz functions; the Newtonian–Sobolev spaces [11]; and the Cheeger-type Sobolev spaces [17]. As explained by Chiron [3], all these notions coincide when the domain of def- inition is an open subset of Rn (or a Riemannian manifold) and the target is a complete separable metric space X (contributions to the proof of these equiva- lences have been given in [3, 11, 19, 22]). -

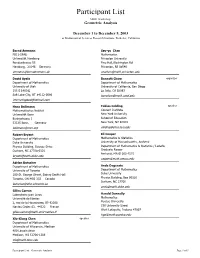

Participant List MSRI Workshop: Geometric Analysis

Participant List MSRI Workshop: Geometric Analysis December 1 to December 5, 2003 at Mathematical Sciences Research Institute, Berkeley, California Bernd Ammann Szu-yu Chen FB11-SPAD Mathematics Universität Hamburg Princeton University Bundesstrasse 55 Fine Hall,Washington Rd Hamburg, 20146 Germany Princeton, NJ 08540 [email protected] [email protected] David Ayala Bennett Chow organizer Department of Mathematics Department of Mathematics University of Utah University of California, San Diego 155 S 1400 E La Jolla, CA 92093 Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0090 [email protected] [email protected] Hans Ballmann Tobias Colding speaker Mathematisches Institut Courant Institute Universität Bonn New York University Beringstrasse 1 School of Education 53125 Bonn, Germany New York, NY 10003 [email protected] [email protected] Robert Bryant Eli Cooper Department of Mathematics Mathematics & Statistics Duke University University of Massachusetts, Amherst Physics Building, Science Drive Department of Mathematics & Statistics / Lederle Durham, NC 27708-0320 Graduate Resear Amherst, MA 01003-4515 [email protected] [email protected] Adrian Butscher Department of Mathematics Anda Degeratu University of Toronto Department of Mathematics 100 St. George Street, Sidney Smith Hall Duke University Toronto, ON M5S 3G3 Canada Physics Building, Box 90320 Durham, NC 27708 [email protected] [email protected] Gilles Carron Laboratoire jean Leray Harold Donnelly Université de Nantes Mathematics 2, rue de la Houssiniere, BP 92208 -

André Arroja Neves

Andr´eArroja Neves Department of Mathematics University of Chicago 5734 S University Ave Chicago, IL 60637 email: [email protected] 1. Education • Stanford University, Stanford, USA Ph. D. in Mathematics, 2000-2005. Thesis advisor: Richard Schoen. • Instituto Superior T´ecnico, Lisboa, Portugal. Licenciatura in Mathematics, 1999. 2. Appointments • 2016 { Present, Professor University of Chicago • Fall 2018, Member of IAS • 2012 { 2016, Professor Imperial College London • 2011 { 2012, Reader Imperial College London • 2009 { 2011, Lecturer Imperial College London • 2007 { 2009, Assistant Professor, Princeton University • 2005 { 2007, Instructor, Princeton University 3. Research Interests • Differential Geometry and Analysis of PDE's. 4. Awards • Member of American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2020 • Simons Investigator Award, 2018 • Oswald Veblen AMS Prize, 2016 • New Horizons in Mathematics Prize, 2016 • Royal Society Wolfson Merit Award, 2015 • LMS Whitehead Prize, 2013 • Philip Leverhulme Prize, 2012 • Excellence in teaching award, Princeton, 2006. 5. Invited Lectures • Pedro Nunes Lectures 2020 Portugal • Current Developments in Mathematics 2019 - Harvard, Boston, USA • Tondeur Lecture Series - Urbana-Champaign, 2019 • Distinguished Lecture - University of Wisconsin, 2018 • Joint AMS-MAA Annual Meeting Plenary Speaker, San Diego 2018 • EMS Distinguished Speaker 2018, Valladolid, Spain 2018 1 • Distinguished Visitor Professor - Fields Institute, Canada, Fall 2017 • Nirenberg Lectures - CRM, Canada, 2015 • ICM Invited Section Speaker, South Korea, 2014 • Rademacher Lectures - UPenn, USA, 2014 • Current Developments in Mathematics 2013 - Harvard, Boston, USA • Barret Lectures - University of Tennessee, USA, 2013 6. Grants • NSF grant DMS 2005468 (2020-2023) • NSF grant DMS 1710846 (2017-2020) • EPSRC Programme Grant(joint with Prof. Topping and Prof. Dafermos)(January 2013 to January 2019) 1,600,000 GBP • ERC Start Grant(January 2012 to January 2017) 1,100,000 EUR • Marie Curie IRG (January 2011 to January 2015) • NSF grant (July 2006 to June 2009) 7. -

![Arxiv:1409.1632V2 [Math.DG] 27 Nov 2018 Hwn Aihn Fti Uri Ieeta N Icsigtecons the O Discussing and Product](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4463/arxiv-1409-1632v2-math-dg-27-nov-2018-hwn-aihn-fti-uri-ieeta-n-icsigtecons-the-o-discussing-and-product-1974463.webp)

Arxiv:1409.1632V2 [Math.DG] 27 Nov 2018 Hwn Aihn Fti Uri Ieeta N Icsigtecons the O Discussing and Product

UNIQUENESS THEOREMS FOR FREE BOUNDARY MINIMAL DISKS IN SPACE FORMS AILANA FRASER AND RICHARD SCHOEN Abstract. We show that a minimal disk satisfying the free boundary condition in a con- stant curvature ball of any dimension is totally geodesic. We weaken the condition to parallel mean curvature vector in which case we show that the disk lies in a three dimen- sional constant curvature submanifold and is totally umbilic. These results extend to higher dimensions earlier three dimensional work of J. C. C. Nitsche and R. Souam. 1. Introduction In this short note we consider the free boundary minimal disks in a ball in Euclidean space or a space N n of constant curvature. These are proper branched minimal immersions of a disk into the ball that meet the boundary orthogonally (the conormal vector of the disk is normal to the boundary of the ball). Such surfaces have been extensively studied and they arise as extremals of the area functional for relative cycles in the ball. They also arise as extremals of a certain eigenvalue problem [FS1] and [FS2]. We show here that any such free boundary minimal disk is a totally geodesic disk passing through the center of the ball. We extend the result to free boundary disks with parallel mean curvature in a ball. If the mean curvature is not zero, we show that such disks are contained in a totally geodesic three dimensional submanifold (an affine subspace in the flat case) and that the disk is totally umbilic. Both of these results are known in case n = 3. -

Reference Yau, Shing-Tong (1949-)

Yau, Shing-Tong I 1233 government manipulation of evidence in the Japanese article by the eminent Chinese American mathemati internmentcases, offeredto bring a challenge to Yasui cian Shiing-Shen Chern. In 1966, Yau entered the and his fellow wartime defendants' convictions by Chinese University of Hong Kong to study mathemat means of a coram nobis petition. Yasui consented, ics but moved three years later to the University of and a legal team headed by Oregon attorney Peggy Californiaat Berkeley to pursue graduate studies under Nagae took up his case. Unlike in the case of Fred Chern. At Berkeley, besides working with Chern in Korematsu, however, Yasui's petition failed to bring differential geometry, Yau also studied differential about a reconsideration of the official malfeasance equations with other professors, believing that cross involved in his prosecution. In 1984, district judge fe1tilizationwas key to the future of mathematics. In Robert C. Belloni issued an order vacating Yasui's depth knowledge of both fields indeed proved to be conviction, in accordance with a motion by Justice crucial to his success as it helped lay the foundation Department officials anxious to dispose of the case, for Yau's research in integrating thetwo. Yau received but declined to either grant Yasui's coram nobis peti his PhD in 1971, after spending less than two years at tion or to make findings of fact regarding the record Berkeley. of official misconduct. Yasui and his lawyers appealed After graduation from Berkeley, Yau went to the the ruling, but he died in ovember 1986, thereby Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton where he mooting the case before the appeal could be decided. -

Research Statement Chao Li

RESEARCH STATEMENT CHAO LI 1. Introduction My research lies in the interface of geometry, analysis and mathematical physics. A funda- mental theme in differential geometry is to understand curvature conditions. Together with my collaborators, I have resolved a number of questions on the global and local geometric and topo- logical affects of scalar curvature. A central technique in my research is the study of geometric variational problems. My most significant contributions can be organized as follows. (A) Scalar curvature is a coarse measure of local bending, making its effects on global topology of a manifold rather delicate. In the last sixty years, there has been dramatic progress on understanding global topological obstructions of manifolds with positive scalar curvature. However, a list of fundamental conjectures have been open. Recently, O. Chodosh and I proved the long-standing \K(π; 1) conjecture" in dimension 4 and 5. This conjecture was proposed by R. Schoen and S.T. Yau [39] in 1987 and inde- pendently by M. Gromov [15] in 1986. Our new observations apply to other previously open problems. For example, in 1988, R. Schoen and S.T. Yau studied the structure of locally con- formally flat manifolds with nonnegative scalar curvature, and established a Liouvelle type theorem for such manifolds with certain technical assumptions. In the same paper [9], O. Chodosh and I completed this Liouvelle type theorem for all locally conformally flat manifolds with nonnegative scalar curvature. (B) In 2013, M. Gromov [16] proposed a geometric comparison theory for manifolds with positive scalar curvature using polyhedrons, aiming to study local geometry and the convergence of metrics with positive scalar curvature. -

Topics in Differential Geometry Minimal Submanifolds Math 286, Spring 2014-2015 Richard Schoen

TOPICS IN DIFFERENTIAL GEOMETRY MINIMAL SUBMANIFOLDS MATH 286, SPRING 2014-2015 RICHARD SCHOEN NOTES BY DAREN CHENG, CHAO LI, CHRISTOS MANTOULIDIS Contents 1. Background on the 2D mapping problem 2 1.1. Hopf Differential 3 1.2. General existence theorem 4 2. Minimal submanifolds and Bernstein theorem 5 2.1. First variation of area functional 5 2.2. Second variation of area functional, Bernstein theorem 5 3. Bernstein's theorem in higher codimensions 8 3.1. Complexifying the stability operator 9 4 4 3.2. Stable minimal surfaces in R and T 11 n 3.3. Stable minimal genus-0 surfaces in R , n ≥ 5 18 4. Positive isotropic curvature 21 4.1. High homotopy groups of PIC manifolds 24 4.2. Fundamental group of PIC manifolds 25 5. Positive scalar curvature 28 5.1. Positive curvature obstructing stability 28 5.2. Bonnet-type theorem 29 5.3. Some obstructions to positive scalar curvature 31 5.4. Asymptotically flat manifolds and ADM mass 32 5.5. Positive mass theorem 34 5.6. Rigidity case 37 6. Calibrated geometry 38 6.1. Definitions and examples 38 6.2. The Special Lagrangian Calibration 41 6.3. Varitational Problems for (special) Lagrangian Submanifolds 44 6.4. Minimizing volume among Lagrangians 48 6.5. Lagrangian 2D mapping problem 50 6.6. Lagrangian cones 51 6.7. Monotonicity and regularity of minimizers in 2D 52 References 56 Date: January 27, 2017. 1 2 NOTES BY DAREN CHENG, CHAO LI, CHRISTOS MANTOULIDIS These are notes from Rick Schoen's topics in differential geometry course taught at Stanford University in the Spring of 2015. -

Leroy P. Steele Prize for Mathematical Exposition 1

AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY LEROY P. S TEELE PRIZE FOR MATHEMATICAL EXPOSITION The Leroy P. Steele Prizes were established in 1970 in honor of George David Birk- hoff, William Fogg Osgood, and William Caspar Graustein and are endowed under the terms of a bequest from Leroy P. Steele. Prizes are awarded in up to three cate- gories. The following citation describes the award for Mathematical Exposition. Citation John B. Garnett An important development in harmonic analysis was the discovery, by C. Fefferman and E. Stein, in the early seventies, that the space of functions of bounded mean oscillation (BMO) can be realized as the limit of the Hardy spaces Hp as p tends to infinity. A crucial link in their proof is the use of “Carleson measure”—a quadratic norm condition introduced by Carleson in his famous proof of the “Corona” problem in complex analysis. In his book Bounded analytic functions (Pure and Applied Mathematics, 96, Academic Press, Inc. [Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers], New York-London, 1981, xvi+467 pp.), Garnett brings together these far-reaching ideas by adopting the techniques of singular integrals of the Calderón-Zygmund school and combining them with techniques in complex analysis. The book, which covers a wide range of beautiful topics in analysis, is extremely well organized and well written, with elegant, detailed proofs. The book has educated a whole generation of mathematicians with backgrounds in complex analysis and function algebras. It has had a great impact on the early careers of many leading analysts and has been widely adopted as a textbook for graduate courses and learning seminars in both the U.S.