Checklist of Inland Aquatic Isopoda (Crustacea: Malacostraca) of California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seasonal Diet Pattern of Non-Native Tubenose Goby (Proterorhinus Semilunaris) in a Lowland Reservoir (Mušov, Czech Republic)

Knowledge and Management of Aquatic Ecosystems (2010) 397, 02 http://www.kmae-journal.org c ONEMA, 2010 DOI: 10.1051/kmae/2010018 Seasonal diet pattern of non-native tubenose goby (Proterorhinus semilunaris) in a lowland reservoir (Mušov, Czech Republic) Z. Adámek(1),P.Jurajda(2),V.Prášek(2),I.Sukop(3) Received March 18, 2010 / Reçu le 18 mars 2010 Revised May 21, 2010 / Révisé le 21 mai 2010 Accepted June 3rd, 2010 / Accepté le 3 juin 2010 ABSTRACT Key-words: The tubenose goby (Proterorhinus semilunaris) is a gobiid species cur- Gobiidae, rently extending its area of distribution in Central Europe. The objective food, of the study was to evaluate the annual pattern of its feeding habits in lowland the newly colonised habitats of the Mušov reservoir on the Dyje River (the reservoir, Danube basin, Czech Republic) with respect to natural food resources. rip-rap bank, In the reservoir, tubenose goby has established a numerous population, the Dyje River densely colonising stony rip-rap banks. Its diet was exclusively of an- imal origin with significant dominance of and preference for two food items – chironomid (Chironomidae) larvae and waterlouse (Asellus aquati- cus), which contributed 40.2 and 27.6%, respectively, to the total food bulk ingested. The index of preponderance for the two items was also very high, amounting to 73.8 and 26.5, respectively. In the annual pat- tern, a remarkable preference for chironomid larvae was recorded in the summer period whilst waterlouse were consumed predominantly in win- ter months. The proportion of other food items was rather marginal – only corixids, copepods, ceratopogonids and cladocerans were of certain mi- nor importance with proportions of 5.4, 4.3, 4.1 and 3.9%, respectively. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/02/2021 05:23:45PM Via Free Access 24 R

Contributions to Zoology, 70 (1) 23-39 (2001) SPB Academic Publishing bv, The Hague Hierarchical analysis of mtDNA variation and the use of mtDNA for isopod (Crustacea: Peracarida: Isopoda) systematics R. Wetzer Invertebrate Zoology, Crustacea, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90007, USA, [email protected] Keywords: 12S rRNA, 16S rRNA, COI, mitochondrial DNA, isopod, Crustacea, molecular Abstract Transition/transversion bias 30 Discussion 32 Nucleotide composition 32 Carefully collected molecular data and rigorous analyses are Transition/transversionbias 34 revolutionizing today’s phylogenetic studies. Althoughmolecular Sequence divergences 34 data have been used to estimate various invertebrate phylogenies Rate variation across 34 lor lineages more than a decade,this is the first ofdifferent study survey Conclusions 35 of regions mitochondrial DNA in isopod crustaceans assessing Acknowledgements 36 sequence divergence and hence the usefulness ofthese regions References 36 to infer phylogeny at different hierarchical levels. 1 evaluate three loci fromthe mitochondrial ribosomal RNAs genome (two (12S, 16S) and oneprotein-coding (COI)) for their appropriateness in inferring isopod phylogeny at the suborder level and below. Introduction The patterns are similar for all three loci with the most speciose suborders ofisopods also having the most divergent mitochondrial The crustacean order Isopoda is important and nucleotide sequences. Recommendations for designing an or- because it has a broad dis- der- or interesting geographic suborder-level molecular study in previously unstudied groups of Crustacea tribution and is diverse. There would include: (1) collecting a minimum morphologically are of two-four species or genera thoughtto be most divergent, (2) more than 10,000 described marine, freshwater, sampling the across of interest as equally as possible in group and terrestrial species, ranging in length from 0.5 terms of taxonomic representation and the distributionofspecies, mm to 440 mm. -

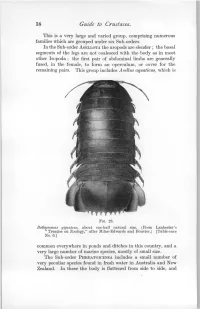

Guide to Crustacea

38 Guide to Crustacea. This is a very large and varied group, comprising numerous families which are grouped under six Sub-orders. In the Sub-order ASELLOTA the uropods are slender ; the basal segments of the legs are not coalesced with the body as in most other Isopoda ; the first pair of abdominal limbs are generally fused, in the female, to form an operculum, or cover for the remaining pairs. This group includes Asellus aquaticus, which is FIG. 23. Bathynomus giganteus, about one-half natural size. (From Lankester's "Treatise on Zoology," after Milne-Edwards and Bouvier.) [Table-case No. 6.] common everywhere in ponds and ditches in this country, and a very large number of marine species, mostly of small size. The Sub-order PHKEATOICIDEA includes a small number of very peculiar species found in fresh water in Australia and New Zealand. In these the body is flattened from side to side, and Peraca rida—Isopoda. 39 the animals in other respects have a superficial resemblance to Amphipoda. In the Sub-order FLABELLIFERA the terminal limbs of the abdomen (uropods) are spread out in a fan-like manner on each side of the telson. Many species of this group, belonging to the family Cymothoidae, are blood-sucking parasites of fish, and some of them are remarkable for being hermaphrodite (like the Cirri- pedia), each animal being at first a male and afterwards a female. Mo' of these parasites are found adhering to the surface of the body, behind the fins or under the gill-covers of the fish. A few, however, become internal parasites like the Artystone trysibia exhibited in this case, which has burrowed into the body of a Brazilian freshwater fish. -

The 17Th International Colloquium on Amphipoda

Biodiversity Journal, 2017, 8 (2): 391–394 MONOGRAPH The 17th International Colloquium on Amphipoda Sabrina Lo Brutto1,2,*, Eugenia Schimmenti1 & Davide Iaciofano1 1Dept. STEBICEF, Section of Animal Biology, via Archirafi 18, Palermo, University of Palermo, Italy 2Museum of Zoology “Doderlein”, SIMUA, via Archirafi 16, University of Palermo, Italy *Corresponding author, email: [email protected] th th ABSTRACT The 17 International Colloquium on Amphipoda (17 ICA) has been organized by the University of Palermo (Sicily, Italy), and took place in Trapani, 4-7 September 2017. All the contributions have been published in the present monograph and include a wide range of topics. KEY WORDS International Colloquium on Amphipoda; ICA; Amphipoda. Received 30.04.2017; accepted 31.05.2017; printed 30.06.2017 Proceedings of the 17th International Colloquium on Amphipoda (17th ICA), September 4th-7th 2017, Trapani (Italy) The first International Colloquium on Amphi- Poland, Turkey, Norway, Brazil and Canada within poda was held in Verona in 1969, as a simple meet- the Scientific Committee: ing of specialists interested in the Systematics of Sabrina Lo Brutto (Coordinator) - University of Gammarus and Niphargus. Palermo, Italy Now, after 48 years, the Colloquium reached the Elvira De Matthaeis - University La Sapienza, 17th edition, held at the “Polo Territoriale della Italy Provincia di Trapani”, a site of the University of Felicita Scapini - University of Firenze, Italy Palermo, in Italy; and for the second time in Sicily Alberto Ugolini - University of Firenze, Italy (Lo Brutto et al., 2013). Maria Beatrice Scipione - Stazione Zoologica The Organizing and Scientific Committees were Anton Dohrn, Italy composed by people from different countries. -

Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee

Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories Compiled by S. Oldfield Edited by D. Procter and L.V. Fleming ISBN: 1 86107 502 2 © Copyright Joint Nature Conservation Committee 1999 Illustrations and layout by Barry Larking Cover design Tracey Weeks Printed by CLE Citation. Procter, D., & Fleming, L.V., eds. 1999. Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Disclaimer: reference to legislation and convention texts in this document are correct to the best of our knowledge but must not be taken to infer definitive legal obligation. Cover photographs Front cover: Top right: Southern rockhopper penguin Eudyptes chrysocome chrysocome (Richard White/JNCC). The world’s largest concentrations of southern rockhopper penguin are found on the Falkland Islands. Centre left: Down Rope, Pitcairn Island, South Pacific (Deborah Procter/JNCC). The introduced rat population of Pitcairn Island has successfully been eradicated in a programme funded by the UK Government. Centre right: Male Anegada rock iguana Cyclura pinguis (Glen Gerber/FFI). The Anegada rock iguana has been the subject of a successful breeding and re-introduction programme funded by FCO and FFI in collaboration with the National Parks Trust of the British Virgin Islands. Back cover: Black-browed albatross Diomedea melanophris (Richard White/JNCC). Of the global breeding population of black-browed albatross, 80 % is found on the Falkland Islands and 10% on South Georgia. Background image on front and back cover: Shoal of fish (Charles Sheppard/Warwick -

Lazare Botosaneanu ‘Naturalist’ 61 Doi: 10.3897/Subtbiol.10.4760

Subterranean Biology 10: 61-73, 2012 (2013) Lazare Botosaneanu ‘Naturalist’ 61 doi: 10.3897/subtbiol.10.4760 Lazare Botosaneanu ‘Naturalist’ 1927 – 2012 demic training shortly after the Second World War at the Faculty of Biology of the University of Bucharest, the same city where he was born and raised. At a young age he had already showed interest in Zoology. He wrote his first publication –about a new caddisfly species– at the age of 20. As Botosaneanu himself wanted to remark, the prominent Romanian zoologist and man of culture Constantin Motaş had great influence on him. A small portrait of Motaş was one of the few objects adorning his ascetic office in the Amsterdam Museum. Later on, the geneticist and evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky and the evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr greatly influenced his thinking. In 1956, he was appoint- ed as a senior researcher at the Institute of Speleology belonging to the Rumanian Academy of Sciences. Lazare Botosaneanu began his career as an entomologist, and in particular he studied Trichoptera. Until the end of his life he would remain studying this group of insects and most of his publications are dedicated to the Trichoptera and their environment. His colleague and friend Prof. Mar- cos Gonzalez, of University of Santiago de Compostella (Spain) recently described his contribution to Entomolo- gy in an obituary published in the Trichoptera newsletter2 Lazare Botosaneanu’s first contribution to the study of Subterranean Biology took place in 1954, when he co-authored with the Romanian carcinologist Adriana Damian-Georgescu a paper on animals discovered in the drinking water conduits of the city of Bucharest. -

Natur Und Heimat

Natur u. Heimat, 37. Jahrg., Heft 3, 1977 (1968): Gehäuse von Insekten-Larven, insbesondere von Chironomiden, in quar tären Sedimenten. Mitt. Geol. Inst. Univers. Hannover, 8, 34-53. ___.:._ HrLTERMANN, H. (1975): Kleiner Führer durch Solbad Laer T. W. Suderberger Hefte 1. - HrL TERMANN, H . (1976): Ein vergessener mittelalterlicher Baustein. Jb. Heimatbund Osnabrück-Land, 54-59. - HrLTERMANN, H. & K. MÄDLER (1977): Charophyten als palökologische Indikatoren und ihr Vorkommen in den Sinterkalken von Bad Laer T. W. Paläontol. Z. (im Druck). - ZEISSLER, H. (1977): Konchylien aus dem holozänen Travertin von Bad Laer, Kreis Osnabrück. (im Druck). Anschrift des Verfassers1: Prof. Dr. H. Hiltermann, Milanring 11, D-4518 Bad Laer. Die ersten Nachweise der Wasserassel Proasellus meridianus CRacovitza, 1919) (Crustacea, Isopoda Asellidae) im Einzugsgebiet der Ems KARL FRIEDRICH HERHAUS, Münster In Deutschland ist die von HENRY und MAGNIEZ (1970) revidierte Familie Asellida,e Sars, 1899, mit drei oberirdischen Arten vertreten. Die am weitesten verbreitete Art ist Asellus ( Asellus) aquaticus (L., 175 8); sie ist ein sibirisches Faunenelement, das sich postglazial nach Westen hin ausgebreitet hat (BrRSTEIN 1951; WILLIAMS 1962). Weitaus weniger häufig tritt die zweite Art, Proasellus coxalis (Dollfus, 1892), auf; diese im übrigen circummediterran verbreitete Art ist in Mittel europa mit der Unterart septentrionalis (Herbst, 1956) vertreten, die vermutlich erst in jüngster Zeit eingeschleppt worden ist (HERHAUS 1977). Am seltensten ist auf deutschem Boden die dritte Art, Proasellus meridianus (Racovitza, 1919). P. meridianus ist eine autochthon west europä,isch-atlantische Form (GRUNER 1965); in Deutschland wurde sie von STAMMER (1932) am linken Niederrhein nachgewiesen. Für die sichere Bestimmung der drei Arten ist die Untersuchung der Pleopoden II unter dem Binokular unerläßlich. -

(Janiridae, Isopoda, Crustacea), a Second Species of Austrofilius in the Mediterranean Sea, with a Discussion on the Evolutionary Biogeography of the Genus J

Austrofilius MAJORICENSIS SP. NOV. (JANIRIDAE, ISOPODA, CRUSTACEA), A SECOND SPECIES OF AUSTROFILIUS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA, WITH A DISCUSSION ON THE EVOLUTIONARY BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE GENUS J. Castelló To cite this version: J. Castelló. Austrofilius MAJORICENSIS SP. NOV. (JANIRIDAE, ISOPODA, CRUSTACEA), A SECOND SPECIES OF AUSTROFILIUS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA, WITH A DISCUS- SION ON THE EVOLUTIONARY BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE GENUS. Vie et Milieu / Life & Environment, Observatoire Océanologique - Laboratoire Arago, 2008, pp.193-201. hal-03246157 HAL Id: hal-03246157 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-03246157 Submitted on 2 Jun 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. VIE ET MILIEU - LIFE AND ENVIRONMENT, 2008, 58 (3/4): 193-201 AUSTROFILIUS MAJORICENSIS SP. NOV. (JANIRIDAE, ISOPODA, CRUSTACEA), A SECOND SPECIES OF AUSTROFILIUS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA, WITH A DISCUSSION ON THE EVOLUTIONARY BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE GENUS J. CASTELLÓ Departament de Didàctica de les Ciències Experimentals i de la Matemàtica, Universitat de Barcelona, Passeig de la Vall d’Hebron 171, 08035 Barcelona, Spain [email protected] ISOPODA Abstract. – A new species of Janiroidean isopod, Austrofilius majoricensis sp. nov., from ASELLOTA JANIRIDAE Majorca (Balearic Islands, Western Mediterranean), is described. -

(Peracarida: Isopoda) Inferred from 18S Rdna and 16S Rdna Genes

76 (1): 1 – 30 14.5.2018 © Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, 2018. Relationships of the Sphaeromatidae genera (Peracarida: Isopoda) inferred from 18S rDNA and 16S rDNA genes Regina Wetzer *, 1, Niel L. Bruce 2 & Marcos Pérez-Losada 3, 4, 5 1 Research and Collections, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, California 90007 USA; Regina Wetzer * [[email protected]] — 2 Museum of Tropical Queensland, 70–102 Flinders Street, Townsville, 4810 Australia; Water Research Group, Unit for Environmental Sciences and Management, North-West University, Private Bag X6001, Potchefstroom 2520, South Africa; Niel L. Bruce [[email protected]] — 3 Computation Biology Institute, Milken Institute School of Public Health, The George Washington University, Ashburn, VA 20148, USA; Marcos Pérez-Losada [mlosada @gwu.edu] — 4 CIBIO-InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Campus Agrário de Vairão, 4485-661 Vairão, Portugal — 5 Department of Invertebrate Zoology, US National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20013, USA — * Corresponding author Accepted 13.x.2017. Published online at www.senckenberg.de/arthropod-systematics on 30.iv.2018. Editors in charge: Stefan Richter & Klaus-Dieter Klass Abstract. The Sphaeromatidae has 100 genera and close to 700 species with a worldwide distribution. Most are abundant primarily in shallow (< 200 m) marine communities, but extend to 1.400 m, and are occasionally present in permanent freshwater habitats. They play an important role as prey for epibenthic fishes and are commensals and scavengers. Sphaeromatids’ impressive exploitation of diverse habitats, in combination with diversity in female life history strategies and elaborate male combat structures, has resulted in extraordinary levels of homoplasy. -

Paradella Dianae – Around the World in 20 Years

Southeastern Regional Taxonomic Center South Carolina Department of Natural Resources Paradella dianae – around the world in 20 years Kingdom Animalia Phylum Arthropoda Class Malacostraca Order Isopoda Family Sphaeromatidae Paradella dianae is a species of crustacean that was accidentally introduced to the southeast coast of the U.S. in the early 1980s. It was first discovered by SCDNR divers who were studying the jetties that were being built at Murrells Inlet at that time. As they made repeated dives on the jetty stones below the low tide level, to carefully and systematically quantify the flora and fauna, divers noticed hundreds of small creatures clinging tightly to their neoprene wetsuits when they climbed from the water back onto the dive boat. It took a lot of effort to remove them, even under the heavy spray of freshwater from a garden hose back at the dock. It turns out that these pesky animals were isopods that are native to the Pacific coasts of North and Central America. They were probably carried to our coast on the outside surfaces of oceangoing ships, and they have hitchhiked around the world among the fouling growth that builds up over time on these ship’s hulls. Although they aren’t particularly conspicuous to the casual observer, isopods are an important part of many coastal communities, as this is especially true for those that live on hard surfaces that are continuously submerged in high salinity seawater for a reasonably long period of time (e.g. floating docks, pilings and jetties). You can learn more about this interesting group of crustaceans by going to the archived ‘Featured Species’ at http://www.dnr.sc.gov/marine/sertc/Isopod%20Crustaceans.pdf Description and Biology: Paradella dianae is a dorso-ventrally flattened, yellowish and brown colored sphaeromatid isopod. -

A Synopsis of the Biology and Life History of Ruffe

J. Great Lakes Res. 24(2): 170-1 85 Internat. Assoc. Great Lakes Res., 1998 A Synopsis of the Biology and Life History of Ruffe Derek H. Ogle* Northland College Mathematics Department Ashland, Wisconsin 54806 ABSTRACT. The ruffe (Gymnocephalus cernuus), a Percid native to Europe and Asia, has recently been introduced in North America and new areas of Europe. A synopsis of the biology and life history of ruffe suggests a great deal of variability exists in these traits. Morphological characters vary across large geographical scales, within certain water bodies, and between sexes. Ruffe can tolerate a wide variety of conditions including fresh and brackish waters, lacustrine and lotic systems, depths of 0.25 to 85 m, montane and submontane areas, and oligotrophic to eutrophic waters. Age and size at maturity dif- fer according to temperature and levels of mortality. Ruffe spawn on a variety ofsubstrates, for extended periods of time. In some populations, individual ruffe may spawn more than once per year. Growth of ruffe is affected by sex, morphotype, water type, intraspecific density, and food supply. Ruffe feed on a wide variety of foods, although adult ruffe feed predominantly on chironomid larvae. Interactions (i.e., competition and predation) with other species appear to vary considerably between system. INDEX WORDS: Ruffe, review, taxonomy, reproduction, diet, parasite, predation. INTRODUCTION DISTRIBUTION This is a review of the existing literature on Ruffe are native to all of Europe except for along ruffe, providing a synopsis of its biology and life the Mediterranean Sea, western France, Spain, Por- history. A review of the existing literature is tugal, Norway, northern Finland, Ireland, and Scot- needed at this time because the ruffe, which is na- land (Collette and Banarescu 1977, Lelek 1987). -

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES an Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES An Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals By Paul Rudy, Jr. Lynn Hay Rudy Oregon Institute of Marine Biology University of Oregon Charleston, Oregon 97420 Contract No. 79-111 Project Officer Jay F. Watson U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 500 N.E. Multnomah Street Portland, Oregon 97232 Performed for National Coastal Ecosystems Team Office of Biological Services Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 Table of Contents Introduction CNIDARIA Hydrozoa Aequorea aequorea ................................................................ 6 Obelia longissima .................................................................. 8 Polyorchis penicillatus 10 Tubularia crocea ................................................................. 12 Anthozoa Anthopleura artemisia ................................. 14 Anthopleura elegantissima .................................................. 16 Haliplanella luciae .................................................................. 18 Nematostella vectensis ......................................................... 20 Metridium senile .................................................................... 22 NEMERTEA Amphiporus imparispinosus ................................................ 24 Carinoma mutabilis ................................................................ 26 Cerebratulus californiensis .................................................. 28 Lineus ruber .........................................................................