PDF Printing 600

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Method of Wittgenstein's Tractatus

The Method of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus: Toward a New Interpretation Nikolay Milkov, University of Paderborn, Germany Abstract This paper introduces a novel interpretation of Wittgenstein‘s Tractatus, a work widely held to be one of the most intricate in the philosophical canon. It maintains that the Tractatus does not develop a theory but rather advances an original logical symbolism, a new instrument that enables one to ―recognize the formal properties of propositions by mere inspection of propositions themselves‖ (6.122). Moreover, the Tractarian conceptual notation offers to instruct us on how better to follow the logic of language, and by that token stands to enhance our ability to think. Upon acquiring the thinking skills that one can develop by working with the new symbolism, one may move on and discard the notation—―throw away the ladder‖ (6.54), as Wittgenstein put it. 1. The New Wittgensteinians This paper introduces a novel interpretation of Wittgenstein‘s Tractatus. In the process, it takes issue with the New Wittgensteinians, in particular Cora Diamond and James Conant,1 who some twenty-five years ago fielded a comprehensive, essentially skeptical interpretation of the entire body of the Tractatus. Diamond and Conant argued that the core propositions of the Tractatus are literally nonsense, gibberish equivalent to phrases like ―piggly wiggle tiggle‖ (Diamond, 2000, p. 151). To be more explicit, Diamond and Conant defended their view that the book‘s core content is philosophically vacuous by arguing (i) that the Tractatus is divided into a body and a frame; (ii) that the Preface, 3.32–3.326, 4–4.003, 4.111–2 and 6.53–6.54 compose the frame (Conant 2001, p. -

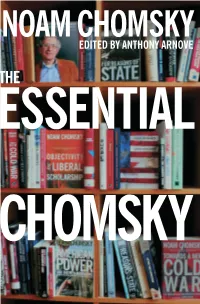

Essential Chomsky

CURRENT AFFAIRS $19.95 U.S. CHOMSKY IS ONE OF A SMALL BAND OF NOAM INDIVIDUALS FIGHTING A WHOLE INDUSTRY. AND CHOMSKY THAT MAKES HIM NOT ONLY BRILLIANT, BUT HEROIC. NOAM CHOMSKY —ARUNDHATI ROY EDITED BY ANTHONY ARNOVE THEESSENTIAL C Noam Chomsky is one of the most significant Better than anyone else now writing, challengers of unjust power and delusions; Chomsky combines indignation with he goes against every assumption about insight, erudition with moral passion. American altruism and humanitarianism. That is a difficult achievement, —EDWARD W. SAID and an encouraging one. THE —IN THESE TIMES For nearly thirty years now, Noam Chomsky has parsed the main proposition One of the West’s most influential of American power—what they do is intellectuals in the cause of peace. aggression, what we do upholds freedom— —THE INDEPENDENT with encyclopedic attention to detail and an unflagging sense of outrage. Chomsky is a global phenomenon . —UTNE READER perhaps the most widely read voice on foreign policy on the planet. ESSENTIAL [Chomsky] continues to challenge our —THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW assumptions long after other critics have gone to bed. He has become the foremost Chomsky’s fierce talent proves once gadfly of our national conscience. more that human beings are not —CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT, condemned to become commodities. THE NEW YORK TIMES —EDUARDO GALEANO HO NE OF THE WORLD’S most prominent NOAM CHOMSKY is Institute Professor of lin- Opublic intellectuals, Noam Chomsky has, in guistics at MIT and the author of numerous more than fifty years of writing on politics, phi- books, including For Reasons of State, American losophy, and language, revolutionized modern Power and the New Mandarins, Understanding linguistics and established himself as one of Power, The Chomsky-Foucault Debate: On Human the most original and wide-ranging political and Nature, On Language, Objectivity and Liberal social critics of our time. -

On the Irrelevance of Transformational Grammar to Second Language Pedagogy

ON THE IRRELEVANCE OF TRANSFORMATIONAL GRAMMAR TO SECOND LANGUAGE PEDAGOGY John T. Lamendella The University of Michigan Many scholars view transformational grammar as an attempt to represent the structure of linguistic knowledge in the mind and seek to apply transformational descriptions of languages to the de- velopment of second language teaching materials. It will be claimed in this paper that it is a mistake to look to transformational gram- mar or any other theory of linguistic description to provide the theoretical basis for either second language pedagogy or a theory of language acquisition. One may well wish to describe the ab- stract or logical structure of a language by constructing a trans- formational grammar which generates the set of sentences identi- fied with that language. However, this attempt should not be con- fused with an attempt to understand the cognitive structures and processes involved in knowing or using a language. It is a cogni- tive theory of language within the field of psycholinguistics rather than a theory of linguistic description which should underlie lan- guage teaching materials. A great deal of effort has been expended in the attempt to demonstrate the potential contributions of the field of descriptive linguistics to the teaching of second languages and, since the theory of transformational grammar has become the dominant theory in the field of linguistics, it is not surprising that applied linguists have sought to apply transformational grammar to gain new in- sights into the teaching of second languages. It will be claimed in this paper that it is a mistake to look to transformational grammar or any other theory of linguistic description to provide the theoretical basis for either second language pedagogy or a theory of language acquisition. -

“Nothing Is Shown”: a 'Resolute' Response

Philosophical Investigations 26:3 July 2003 ISSN 0190-0536 “Nothing is Shown”: A ‘Resolute’ Response to Mounce, Emiliani, Koethe and Vilhauer Rupert Read and Rob Deans, University of East Anglia Part 1: On Mounce on Wittgenstein (Early and Late) on ‘Saying and Showing’ H. O. Mounce published in this journal two years ago now a Criti- cal Notice of the The New Wittgenstein,1 an anthology (edited by Alice Crary and Rupert Read) which is evenly divided between work on Wittgenstein’s early and later writings. The bulk of Mounce’s article was devoted to those contributions primarily con- cerned with the Tractatus.2 There is a straightforward sense in which this selective focus is natural. The pertinent contributions – most conspicuously those by Cora Diamond and James Conant – describe a strikingly un- orthodox interpretation of Wittgenstein’s early book on which it is depicted as having an anti-metaphysical aim. Mounce takes an inter- est in this interpretation because he believes that, in characterizing the Tractatus in anti-metaphysical terms, it misrepresents the central Tractarian doctrine of ‘saying and showing’ – a doctrine which he understands in terms of the idea that “metaphysical truths, though they cannot be stated, may nevertheless be shown”(186). Mounce argues that Diamond and Conant et al. fail to treat this doctrine as “one that Wittgenstein himself advances,” and he claims that they therefore make Wittgenstein’s thought “less original than one might otherwise suppose” (186) by implying that it is “indistinguishable from positivism” in the sense of “not even attempt[ing] to provide positive knowledge [and] confin[ing] itself to removing the confu- 1. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 11-Dec-2009 I, Marjon E. Kamrani , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science It is entitled: "Keeping the Faith in Global Civil Society: Illiberal Democracy and the Cases of Reproductive Rights and Trafficking" Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Anne Runyan, PhD Laura Jenkins, PhD Joel Wolfe, PhD 3/3/2010 305 Keeping the Faith in Global Civil Society: Illiberal Democracy and the Cases of Reproductive Rights and Trafficking A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science of the College of Arts and Science by Marjon Kamrani M.A., M.P.A. University of Texas B.A. Miami University March 2010 Committee Chair: Anne Sisson Runyan, Ph.D ABSTRACT What constitutes global civil society? Are liberal assumptions about the nature of civil society as a realm autonomous from and balancing the power of the state and market transferrable to the global level? Does global civil society necessarily represent and/or result in the promotion of liberal values? These questions guided my dissertation which attempts to challenge dominant liberal conceptualizations of global civil society. To do so, it provides two representative case studies of how domestic and transnational factions of the Religious Right, acting in concert with (or as agents of) the US state, and the political opportunity structures it has provided under conservative regimes, gain access to global policy-making forums through a reframing of international human rights discourses and practices pertaining particularly to women’s rights in order to shift them in illiberal directions. -

Depending on Evil an Analysis of Late Antique Christian Demonologies

Depending on Evil An Analysis of Late Antique Christian Demonologies Thomas Andruszewski 2/17/2008 Table of Contents Preface ........................................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................1 Part I - In Support of Apocalypse Chapter I - Justin Martyr, Athenagoras and Tertullian................................................................................7 Chapter II - Origen .....................................................................................................................................23 Chapter III - Augustine of Hippo ................................................................................................................33 Part II - Demonizing Demons: the Construction of Evil in Late Antiquity Chapter IV - Taking Aim, the Role of Demons in the Polemical Arsenal of Early Church Fathers...........39 Conclusion ..................................................................................................................................................55 1 Preface This thesis provides an analysis of the demonologies included in the writings of some of the early Church Fathers. They include: Justin Martyr’s Apology (150 CE),1 Athenagoras’ Legatio (177 CE),2 Tertullian’s Apology (197 CE),3 Origen’s On First Principles (218 CE)4 and Against Celsus (248 CE),5 -

Ingo Berensmeyer Literary Culture in Early Modern England, 1630–1700

Ingo Berensmeyer Literary Culture in Early Modern England, 1630–1700 Ingo Berensmeyer Literary Culture in Early Modern England, 1630–1700 Angles of Contingency This book is a revised translation of “Angles of Contingency”: Literarische Kultur im England des siebzehnten Jahrhunderts, originally published in German by Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 2007, as vol. 39 of the Anglia Book Series. ISBN 978-3-11-069130-6 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-069137-5 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-069140-5 DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110691375 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020934495 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available from the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. ©2020 Ingo Berensmeyer, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com. Cover image: Jan Davidszoon de Heem, Vanitas Still Life with Books, a Globe, a Skull, a Violin and a Fan, c. 1650. UtCon Collection/Alamy Stock Photo. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Preface to the Revised Edition This book was first published in German in 2007 as volume 39 of the Anglia Book Series. In returning to it for this English version, I decided not simply to translate but to revise it thoroughly in order to correct mistakes, bring it up to date, and make it a little more reader-friendly by discarding at least some of its Teutonic bag- gage. -

The Language Faculty – Mind Or Brain?

The Language Faculty – Mind or Brain? TORBEN THRANE Aarhus University, School of Business, Denmark Artiklens sigte er at underkaste Chomskys nyskabende nominale sammensætning – “the mind/brain” – en nøjere undersøgelse. Hovedargumentet er at den skaber en glidebane, således at det der burde være en funktionel diskussion – hvad er det hjernen gør når den behandler sprog? – i stedet bliver en systemdiskussion – hvad er den interne struktur af den menneskelige sprogevne? Argumentet søges ført igennem under streng iagttagelse af de kognitive videnskabers opfattelse af information og repræsentation, specielt som forstået af den amerikanske filosof Frederick I. Dretske. 1. INTRODUCTION Cartesian dualism is dead, but the central problems it was supposed to solve persist: What kinds of substances exist? Are bodily things (only) physical, mental ‘things’ (only) metaphysical? How is the mental related to the physical? Although “we are all materialists now”, such questions still need answers, and they still need answers from within realist and naturalist bounds to count as scientific. Linguistics is a discipline that may be expected to contribute with answers to such questions. No one in their right mind would deny that our ability to acquire and use human language is lodged between our ears – inside our heads. That is, in our brains and/or minds. In some quarters it has been customary for the past 50 odd years or so to regard this ability as a distinct and dedicated cognitive ability on a par with our abilities to see (vision) or to keep our balance (equilibrioception), and to refer to it as the Human Language Faculty (HLF). This has been the axiomatic starting point for the development of main stream generative linguistics as founded by Chomsky in 1955 in what I shall refer to as ‘Chomsky’s programme’. -

Anti-War Movement Online, Preprint

The UK Anti-War Movement Online: Uses and Limitations of Internet 1 Technologies for Contemporary Activism Kevin Gillan, University of Manchester [email protected] Abstract This article uses interviews with committed anti-war and peace activists to offer an overview of both the benefits and challenges that social movements derive from new communication technologies. It shows contemporary political activism to be intensely informational; dependent on the sensitive adoption of a wide range of communication technologies. A hyperlink analysis is then employed to map the UK anti-war movement as it appears online. Through comparing these two sets of data it becomes possible to contrast the online practices of the UK anti-war movement with its offline ‘reality’. When encountered away from the Web recent anti-war contention is grounded in national-level political realities and internally divided by its political diversity but to the extent that experience of the movement is mediated online, it routinely transcends national and political boundaries. Keywords Anti-war movement; Internet; email; hyperlink analysis. This is a preprint of an article submitted for consideration in the Information Communication & Society , 2008 © Taylor and Francis. Information Communication & Society is available online at: http://journalsonline.tandf.co.uk/ 1 Introduction – Connecting the ‘Virtual’ and the ‘Real’ Internet communication has become vital to social movement organizations and participation in the latest anti-war movements has been boosted by activists’ Internet practices (Nah, Veenstra and Shah 2006). The more central the Internet has come to political activism, the more it has become the route through which individuals first experience key collective actors. -

The Ethics of Disbelief: What Does New Atheism Mean for America? an Honors Thesis for the Department of Religion Marysa E. Shere

The Ethics of Disbelief: What Does New Atheism Mean for America? An honors thesis for the Department of Religion Marysa E. Sheren Tufts University ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my deep gratitude to Laura Doane and the generous donors who make the Tufts Summer Scholars grant program possible, and to Professor Elizabeth Lemons, who served as my mentor throughout my completion of the program in the summer of 2011. That summer of research was the time during which this project first took root, and I am so grateful to those who have taken an interest and invested in my research on New Atheism. TABLE OF CONTENTS The Ethics of Disbelief: An Introduction....................................................................... 1-10 Chapters Chapter 1: THE “SECULAR” AND THE “RELIGIOUS”......................................... 11-29 Chapter 2: IS RELIGION INHERENTLY VIOLENT?.............................................. 30-51 Chapter 3: RELIGION, NEW ATHEISM AND AMERICAN PUBLIC LIFE .......... 51-77 Looking Forward: A Conclusion .......................................................................................77 Bibliography .................................................................................................................iv-ix iii The Ethics of Disbelief: An Introduction Journalists have used the term “New Atheism” to describe a 21st-century movement spurred by the success of several non-fiction books. These books, authored by hard-line secularists and consumed by millions, have made a particularly large splash in the United States over the past five years, sparking a national public debate about God and religion. In this introductory segment of my paper, I will explain what distinguishes New Atheism from other kinds of atheism, and will identify the factors that have led the American public and mainstream media to interpret New Atheism as a “new” social and intellectual innovation. -

A Human Rights Approach to Policing Protest

House of Lords House of Commons Joint Committee on Human Rights Demonstrating respect for rights? A human rights approach to policing protest Seventh Report of Session 2008–09 Volume I Report, together with formal minutes and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 3 March 2009 Ordered by the House of Lords to be printed 3 March 2009 HL Paper 47-I HC 320-I Published on 23 March 2009 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 Joint Committee on Human Rights The Joint Committee on Human Rights is appointed by the House of Lords and the House of Commons to consider matters relating to human rights in the United Kingdom (but excluding consideration of individual cases); proposals for remedial orders, draft remedial orders and remedial orders. The Joint Committee has a maximum of six Members appointed by each House, of whom the quorum for any formal proceedings is two from each House. Current membership HOUSE OF LORDS HOUSE OF COMMONS Lord Bowness John Austin MP (Labour, Erith & Thamesmead) Lord Dubs Mr Andrew Dismore MP (Labour, Hendon) (Chairman) Lord Lester of Herne Hill Dr Evan Harris MP (Liberal Democrat, Oxford West & Lord Morris of Handsworth OJ Abingdon) The Earl of Onslow Mr Virendra Sharma MP (Labour, Ealing, Southall) Baroness Prashar Mr Richard Shepherd MP (Conservative, Aldridge-Brownhills) Mr Edward Timpson MP (Conservative, Crewe & Nantwitch) Powers The Committee has the power to require the submission of written evidence and documents, to examine witnesses, to meet at any time (except when Parliament is prorogued or dissolved), to adjourn from place to place, to appoint specialist advisers, and to make Reports to both Houses. -

Download the Programme for the Winter Gathering

January 2010 Nottingham Organised in cooperation with Nottingham Student Peace Movement and Notts Anti-Militarism Sumac Centre, 245 Gladstone St NG7 6HX Peace News, established in June 1936, is Britain’s oldest peace publication, appearing ten times a year. Co-edited by Emily Johns and Milan Rai, PN reports anti-war news, dissects official propaganda and hosts debates on issues of concern to anti-militarists and others using nonviolence to achieve social change. Peace News opposes the brutal wars in Iraq and Afghanistan - and throughout the world - and the retention and renewal of nuclear weapons in the shape of Trident. But these are only the most extreme forms of the violence which is inherent in our society. This violence manifests also as sexism, racism, homophobia, hunger, inequality, corporate domination, government repression and the exploitation of people, animals and the environment. Peace News seeks to oppose all forms of violence, and to create positive change based on co-operation and responsibility. To create a nonviolent world, we believe we must avoid violence in our struggle for change. Peace News draws on the traditions of pacifism, feminism, anarchism, socialism, human rights, animal rights, and green politics - without dogma, but in the spirit of openness. Britain’s entire arrogant and aggressive foreign policy is unpopular among British people. In March 2007, a Telegraph poll asked whether people agreed with this statement: “Some people say that, although Britain is now only a middle-ranking power, Britain should as a nation continue to try to ‘punch above its weight’ – that is, have more influence in the world than our military and economic strength would seem to indicate.” 55% said no, Britain should not “punch above its weight”.