Catering to Multiple Audiences: Language Diversity in Singapore's Chinatown Food Stall Displays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linguistic Landscapes

Chapter 21 Linguistic Landscapes Luk Van Mensel, Mieke Vandenbroucke, and Robert Blackwood Introduction The study of the linguistic landscape (LL) focuses on the representations of language(s) in public space. Its object of research can be any visible display of written language (a “sign”) as well as people’s interactions with these signs. As a consequence, it is a highly interdisciplinary research domain, grounded in a wide range of theories and disciplines, such as language policy, sociology, semiotics, literacy studies, anthropology, social and human geography, politics, and urban studies. As such, the LL emerges as a promising terrain for the study of language and society. Landry and Bourhis (1997) were the first to provide a clear definition of “linguistic landscape,” which is often built on in LL studies: The language of public road signs, advertising billboards, street names, place names, commercial shop signs, and public signs on government buildings combines to form the linguistic landscape of a given territory, region, or urban agglomeration. (Landry and Bourhis, 1997: 25) Since then, however, the notion of what constitutes LL research has clearly expanded. The field has both integrated and embraced various theoretical and epistemological viewpoints, has developed new methodologies, and now covers a range of linguistic artifacts that go far beyond those originally listed by Landry and Bourhis. As a result, present- day LL research can be described as kaleidoscopic in nature. LLs are mainly studied in urban settings (hence the “multilingual cityscape”; Gorter, 2006b), unsur- prising given the stimulating visual and linguistic environment that the present-day glo- balized city has to offer, but scholars have also looked at more peripheral and rural areas (e.g., Kotze and du Plessis, 2010; Pietikäinen, Lane, Salo, and Laihiala-Kankainen, 2011). -

Insider People · Places · Events · Dining · Nightlife

APRIL · MAY · JUNE SINGAPORE INSIDER PEOPLE · PLACES · EVENTS · DINING · NIGHTLIFE INSIDE: KATONG-JOO CHIAT HOT TABLES CITY MUST-DOS AND MUCH MORE Ready, set, shop! Shopping is one of Singapore’s national pastimes, and you couldn’t have picked a better time to be here in this amazing city if you’re looking to nab some great deals. Score the latest Spring/Summer goods at the annual Fashion Steps Out festival; discover emerging local and regional designers at trade fair Blueprint; or shop up a storm when The Great Singapore Sale (3 June to 14 August) rolls around. At some point, you’ll want to leave the shops and malls for authentic local experiences in Singapore. Well, that’s where we come in – we’ve curated the best and latest of the city in this nifty booklet to make sure you’ll never want to leave town. Whether you have a week to deep dive or a weekend to scratch the surface, you’ll discover Singapore’s secrets at every turn. There are rich cultural experiences, stylish bars, innovative restaurants, authentic local hawkers, incredible landscapes and so much more. Inside, you’ll find a heap of handy guides – from neighbourhood trails to the best eats, drinks and events in Singapore – to help you make the best of your visit to this sunny island. And these aren’t just our top picks: we’ve asked some of the city’s tastemakers and experts to share their favourite haunts (and then some), so you’ll never have a dull moment exploring this beautiful city we call home. -

Language Attitudes and Linguistic Landscapes of Malawi Mark Visonà

Language Attitudes and Linguistic Landscapes of Malawi Mark Visonà Georgetown University 1. Introduction Previous studies in perceptual dialectology, or the study of non-linguists’ understandings of linguistic variation, have largely focused on identifying the social meanings that people assign to language depending on where and by whom it is used. Developed by Preston (1981), perceptual dialectology seeks to identify the specific linguistic features that play roles in triggering attitudes towards language, further aiming to discover the underlying beliefs or ideologies that motivate these attitudes (Preston, 2013, p. 160). In this paper, I identify attitudes regarding linguistic diversity in the multilingual African country of Malawi, additionally proposing that one factor shaping a speaker’s attitudes toward language use is the representation of language in their environment, or their linguistic landscape. This new approach investigates language attitudes at both the individual and societal level, ultimately contributing to our understanding of how non-linguists notice and understand language variation. The study of linguistic landscapes, or the entirety of ways that language appears in a public space, has recently emerged as a way for sociolinguists to investigate the interplay between language and its social value in a community (Landry & Bourhis, 1999; Shohamy et al., 2010). Analysis of language tokens on a variety of objects like billboards, advertisements, or road signs may reveal whether certain languages are privileged or disfavored by different social groups. In this paper, I argue that people’s attitudes towards linguistic variation are reflected by their linguistic landscapes, and crucially, are shaped by them as well. I present research that identifies attitudes towards language use in Southern Malawi, a region with multiple minority languages at risk of disappearing (Moyo, 2003). -

Linguistic Landscapes in a Multilingual World

Annual Review of Applied Linguistics (2013), 33, 190–212. © Cambridge University Press, 2013, 0267-1905/13 $16.00 doi: 10.1017/S0267190513000020 Linguistic Landscapes in a Multilingual World Durk Gorter This article offers an overview of the main developments in the field of linguis- tic landscape studies. A large number of research projects and publications indicate an increasing interest in applied linguistics in the use of written texts in urban spaces, especially in bilingual and multilingual settings. The article looks into some of the pioneer studies that helped open up this line of research and summarizes some of the studies that created the springboard for its rapid expansion in recent years. The focus is on current research (from 2007 onward), including studies that illustrate main theoretical approaches and methodologi- cal development as key issues of the expanding field, in particular when applied in settings of societal multilingualism. Publications on the linguistic landscape cover a wide range of innovative theoretical and empirical studies that deal with issues related to multilingual- ism, literacy, multimodality, language policy, linguistic diversity, and minority languages, among others. The article shows some examples of the use of the linguistic landscape as a research tool and a data source to address a num- ber of issues in multilingualism. The article also explores some possible future directions. Overall, the various emerging perspectives in linguistic landscape research can deepen our understanding of languages in urban spaces, language users, and societal multilingualism in general. PANORAMA OF THE FIELD Language learning is the main product of the Rosetta Stone company. Its kiosks can be found in shopping malls and at airports across the United States, and its offices are all over the world. -

Lublin Studies in Modern Languages and Literature

Lublin Studies in Modern Languages and Literature VOL. 43 No 4 (2019) FACULTY OF HUMANITIES MARIA CURIE-SKŁODOWSKA UNIVERSITY LUBLIN STUDIES IN MODERN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURE UMCS 43(4)2019 http://journals.umcs.pl/lsml ii e-ISSN:.2450-4580. Publisher:.. Maria.Curie-Skłodowska.University.. Lublin,.Poland. Maria.Curie-Skłodowska.University.Press. MCSU.Library.building,.3rd.floor. ul ..Idziego.Radziszewskiego.11,.20-031.Lublin,.Poland. phone:.(081).537.53.04. e-mail:.sekretariat@wydawnictwo .umcs .lublin .pl www .wydawnictwo .umcs .lublin .pl Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Jolanta Knieja,.Maria.Curie-Skłodowska.University,.Lublin,.Poland Deputy Editors-in-Chief Jarosław Krajka,.Maria.Curie-Skłodowska.University,.Lublin,.Poland Anna Maziarczyk,.Maria.Curie-Skłodowska.University,.Lublin,.Poland Statistical Editor Tomasz Krajka,.Lublin.University.of.Technology,.Poland. International Advisory Board Anikó Ádám,.Pázmány.Péter.Catholic.University,.Hungary. Monika Adamczyk-Garbowska,.Maria.Curie-Sklodowska.University,.Poland. Ruba Fahmi Bataineh,.Yarmouk.University,.Jordan. Alejandro Curado,.University.of.Extramadura,.Spain. Saadiyah Darus,.National.University.of.Malaysia,.Malaysia. Janusz Golec,.Maria.Curie-Sklodowska.University,.Poland. Margot Heinemann,.Leipzig.University,.Germany. Christophe Ippolito,.Georgia.Institute.of.Technology,.United.States.of.America. Vita Kalnberzina,.University.of.Riga,.Latvia. Henryk Kardela,.Maria.Curie-Sklodowska.University,.Poland. Ferit Kilickaya,.Mehmet.Akif.Ersoy.University,.Turkey. Laure Lévêque,.University.of.Toulon,.France. Heinz-Helmut Lüger,.University.of.Koblenz-Landau,.Germany. Peter Schnyder,.University.of.Upper.Alsace,.France. Alain Vuillemin,.Artois.University,.France. v Indexing Peer Review Process 1 . Each.article.is.reviewed.by.two.independent.reviewers.not.affiliated.to.the.place.of. work.of.the.author.of.the.article.or.the.publisher . 2 . -

Fulcrum-E-Brochure.Pdf

BORN OF WATER BORNE ON AIR The genesis of Fulcrum is inspired by the sublime mysteries of water and air. In developing Fulcrum, these two elemental forces are brought together in an elegant balance, creating an ethereal aura all around. The artistically-tilted architecture and intricate interlocking stacking of the units allow for spectacular vistas of the sea, the pool or the city from each apartment while injecting a sense of airiness in the architecture. The inspiration of balance carries through to the unique pivot-like structural feature, which appears to hold up the building. Even the landscaping is an art of geometry, designed to provide a modest presence that blends seamlessly with the architecture and its surroundings. You enjoy being the centre of attention. You balance your work and play time equally. You seek equilibrium in everything you do. Now, you can be who you are at last. Live free. Live happy. Live the life you’ve always wanted. Everyone else can keep their opinions to themselves. Because you make the rules at Fulcrum. Artist’s Impression Sun and fun await at the East Coast beach, WEEKEND BOARD MEETINGS? just a stone’s throw away. Poised virtually on the edge of the sea, Fulcrum places you minutes from the plethora of activities that Singapore’s famous East Coast beach offers. Catch the waves, worship the sun, build sandcastles with the wind in your hair. Here is where you can make the most of your youthful exuberance in the company of family and friends. BRING IT ON. Who cares if you have to work tomorrow? Today, you are the boss. -

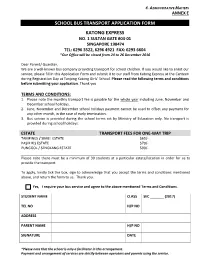

School Bus Transport Application Form

4. ADMINISTRATIVE MATTERS ANNEX E SCHOOL BUS TRANSPORT APPLICATION FORM KATONG EXPRESS NO. 1 SULTAN GATE #04-01 SINGAPORE 198474 TEL: 6296 3522, 6296 4921 FAX: 6293 6604 *Our Office will be closed from 24 to 26 December 2016 Dear Parent/ Guardian, We are a well-known bus company providing transport for school children. If you would like to enlist our service, please fill in this Application Form and submit it to our staff from Katong Express at the Canteen during Registration Day at Tanjong Katong Girls’ School. Please read the following terms and conditions before submitting your application. Thank you. TERMS AND CONDITIONS: 1. Please note the monthly transport fee is payable for the whole year including June, November and December school holidays. 2. June, November and December school holidays payment cannot be used to offset any payment for any other month, in the case of early termination. 3. Bus service is provided during the school terms set by Ministry of Education only. No transport is provided during school holidays. ESTATE TRANSPORT FEES FOR ONE-WAY TRIP TAMPINES / SIMEI ESTATE $65/- PASIR RIS ESTATE $70/- PUNGGOL / SENGKANG ESTATE $90/- Please note there must be a minimum of 30 students at a particular estate/location in order for us to provide the transport. To apply, kindly tick the box, sign to acknowledge that you accept the terms and conditions mentioned above, and return the form to us. Thank you. Yes, I require your bus service and agree to the above mentioned Terms and Conditions. STUDENT NAME CLASS SEC _______ (2017) TEL NO H/P NO ADDRESS PARENT NAME H/P NO SIGNATURE DATE *Please note that the school is only a facilitator in this arrangement. -

Download Map and Guide

Bukit Pasoh Telok Ayer Kreta Ayer CHINATOWN A Walking Guide Travel through 14 amazing stops to experience the best of Chinatown in 6 hours. A quick introduction to the neighbourhoods Kreta Ayer Kreta Ayer means “water cart” in Malay. It refers to ox-drawn carts that brought water to the district in the 19th and 20th centuries. The water was drawn from wells at Ann Siang Hill. Back in those days, this area was known for its clusters of teahouses and opera theatres, and the infamous brothels, gambling houses and opium dens that lined the streets. Much of its sordid history has been cleaned up. However, remnants of its vibrant past are still present – especially during festive periods like the Lunar New Year and the Mid-Autumn celebrations. Telok Ayer Meaning “bay water” in Malay, Telok Ayer was at the shoreline where early immigrants disembarked from their long voyages. Designated a Chinese district by Stamford Raffles in 1822, this is the oldest neighbourhood in Chinatown. Covering Ann Siang and Club Street, this richly diverse area is packed with trendy bars and hipster cafés housed in beautifully conserved shophouses. Bukit Pasoh Located on a hill, Bukit Pasoh is lined with award-winning restaurants, boutique hotels, and conserved art deco shophouses. Once upon a time, earthen pots were produced here. Hence, its name – pasoh, which means pot in Malay. The most vibrant street in this area is Keong Saik Road – a former red-light district where gangs and vice once thrived. Today, it’s a hip enclave for stylish hotels, cool bars and great food. -

Katong/Joo Chiat

Rediscover the KATONG EAST JOO CHIAT To know more about our heritage neighbourhoods and city planning, check out URA's visitor centre where little nooks KATONG JOO CHIAT WALKING MAP located at The URA Centre, of nostalgia mingle 45 Maxwell Road, Singapore 069118 Tel : (65) 6321 8321 Fax : (65) 6226 3549 Email : [email protected] Web : www.ura.gov.sg/gallery with modernity We are open from Mondays to Saturdays, 9am to 5pm Admission is free To make Singapore a great city to live, work and play in In the beginning.... Katong/Joo Chiat has its beginnings in the early 19th Century where coconut plantations stretching from Geylang River to Siglap Road and humble attap-roofed kampung (villages) dotted the landscape. Up to the 1950s, the area was an idyllic seaside retreat for the wealthy. Joo Chiat Road was a simple dirt track running through the plantations from Geylang Serai to the sea in the 1920s. It was named after Chew Joo Chiat, a wealthy land-owner and philanthropist, who bought over large plots of land in Katong and was known as the “King of Katong”. In the 1920s and 1930s, many communities moved eastward out of the city centre to make Katong/Joo Chiat their home. This resulted in bungalows, shophouses and places of worship being built, a reflection of the multi- cultural and varied Katong/Joo Chiat community. The rebuilding of the nation after World War II and the independence of Singapore, transformed the façade of Katong/Joo Chiat. To retain its rich architecture and heritage, over 800 buildings in the area have been conserved. -

Past, Present and Future: Conserving the Nation’S Built Heritage 410062 789811 9

Past, Present and Future: Conserving the Nation’s Built Heritage Today, Singapore stands out for its unique urban landscape: historic districts, buildings and refurbished shophouses blend seamlessly with modern buildings and majestic skyscrapers. STUDIES URBAN SYSTEMS This startling transformation was no accident, but the combined efforts of many dedicated individuals from the public and private sectors in the conservation-restoration of our built heritage. Past, Present and Future: Conserving the Nation’s Built Heritage brings to life Singapore’s urban governance and planning story. In this Urban Systems Study, readers will learn how conservation of Singapore’s unique built environment evolved to become an integral part of urban planning. It also examines how the public sector guided conservation efforts, so that building conservation could evolve in step with pragmatism and market considerations Heritage Built the Nation’s Present and Future: Conserving Past, to ensure its sustainability through the years. Past, Present “ Singapore’s distinctive buildings reflect the development of a nation that has come of age. This publication is timely, as we mark and Future: 30 years since we gazetted the first historic districts and buildings. A larger audience needs to learn more of the background story Conserving of how the public and private sectors have creatively worked together to make building conservation viable and how these efforts have ensured that Singapore’s historic districts remain the Nation’s vibrant, relevant and authentic for locals and tourists alike, thus leaving a lasting legacy for future generations.” Built Heritage Mrs Koh-Lim Wen Gin, Former Chief Planner and Deputy CEO of URA. -

Participating Merchants Address Postal Code Club21 3.1 Phillip Lim 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 A|X Armani Exchange

Participating Merchants Address Postal Code Club21 3.1 Phillip Lim 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 A|X Armani Exchange 2 Orchard Turn, B1-03 ION Orchard 238801 391 Orchard Road, #B1-03/04 Ngee Ann City 238872 290 Orchard Rd, 02-13/14-16 Paragon #02-17/19 238859 2 Bayfront Avenue, B2-15/16/16A The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands 018972 Armani Junior 2 Bayfront Avenue, B1-62 018972 Bao Bao Issey Miyake 2 Orchard Turn, ION Orchard #03-24 238801 Bonpoint 583 Orchard Road, #02-11/12/13 Forum The Shopping Mall 238884 2 Bayfront Avenue, B1-61 018972 CK Calvin Klein 2 Orchard Turn, 03-09 ION Orchard 238801 290 Orchard Road, 02-33/34 Paragon 238859 2 Bayfront Avenue, 01-17A 018972 Club21 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Club21 Men 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Club21 X Play Comme 2 Bayfront Avenue, #B1-68 The Shoppes At Marina Bay Sands 018972 Des Garscons 2 Orchard Turn, #03-10 ION Orchard 238801 Comme Des Garcons 6B Orange Grove Road, Level 1 Como House 258332 Pocket Commes des Garcons 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 DKNY 290 Orchard Rd, 02-43 Paragon 238859 2 Orchard Turn, B1-03 ION Orchard 238801 Dries Van Noten 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Emporio Armani 290 Orchard Road, 01-23/24 Paragon 238859 2 Bayfront Avenue, 01-16 The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands 018972 Giorgio Armani 2 Bayfront Avenue, B1-76/77 The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands 018972 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Issey Miyake 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Marni 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Mulberry 2 Bayfront Avenue, 01-41/42 018972 -

Chosan Zakka Peranakan Travel Guide

CHOSAN ZAKKA Travel Guide Visit Singapore with a different pair of lens. Discover places that cannot be found on travel books. Visit Us at: 304 Orchard Road #04-58, Lucky Plaza Singapore 238863 Exploring Peranakan Culture with Chosan Zakka Peranakan (also known as Straits-born Chinese) are descendants of Chinese traders who settled down along the Straits of Southeast Asia and adopted the local indigenous lifestyle. Three main areas where the Peranakans resided were Penang, Malacca and Singapore. The males are called Baba and the females are called Nonya. To some extent, the Portuguese, Dutch and Indonesian influenced the Peranakan culture and heritage. Till today, you would be able to visit and identify distinctive Peranakan architecture around Singapore. Some have turned into great cafes and some have turned into Instagram-worthy spots for the tourists. Today, we would like to share with you places that we believe still contains rich timeless Peranakan heritage. Here is a little photo guide for you to visit these amazing places! This is the most accessible Peranakan-spot Emerald Hill for tourists as it is right across Somerset@313. Strolling through the beautiful streets and shophouse brings you away from the hustle and bustle of the city. Enjoy a cup of coffee or beer while you are there! Koon Seng Road & Joo Chiat Road While it does not have a nearby train station, it is still worth a go as Joo Chiat was designated as Singapore’s first “heritage town” in 2011. It’s a historical gem well-loved by Singaporeans. Explore the vibrant, gorgeous Peranakan houses that line the streets and also spot murals painted by Ernest Zacharevic, a Lithuanian artist based in Penang.