Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Index

General Index Italicized page numbers indicate figures and tables. Color plates are in- cussed; full listings of authors’ works as cited in this volume may be dicated as “pl.” Color plates 1– 40 are in part 1 and plates 41–80 are found in the bibliographical index. in part 2. Authors are listed only when their ideas or works are dis- Aa, Pieter van der (1659–1733), 1338 of military cartography, 971 934 –39; Genoa, 864 –65; Low Coun- Aa River, pl.61, 1523 of nautical charts, 1069, 1424 tries, 1257 Aachen, 1241 printing’s impact on, 607–8 of Dutch hamlets, 1264 Abate, Agostino, 857–58, 864 –65 role of sources in, 66 –67 ecclesiastical subdivisions in, 1090, 1091 Abbeys. See also Cartularies; Monasteries of Russian maps, 1873 of forests, 50 maps: property, 50–51; water system, 43 standards of, 7 German maps in context of, 1224, 1225 plans: juridical uses of, pl.61, 1523–24, studies of, 505–8, 1258 n.53 map consciousness in, 636, 661–62 1525; Wildmore Fen (in psalter), 43– 44 of surveys, 505–8, 708, 1435–36 maps in: cadastral (See Cadastral maps); Abbreviations, 1897, 1899 of town models, 489 central Italy, 909–15; characteristics of, Abreu, Lisuarte de, 1019 Acequia Imperial de Aragón, 507 874 –75, 880 –82; coloring of, 1499, Abruzzi River, 547, 570 Acerra, 951 1588; East-Central Europe, 1806, 1808; Absolutism, 831, 833, 835–36 Ackerman, James S., 427 n.2 England, 50 –51, 1595, 1599, 1603, See also Sovereigns and monarchs Aconcio, Jacopo (d. 1566), 1611 1615, 1629, 1720; France, 1497–1500, Abstraction Acosta, José de (1539–1600), 1235 1501; humanism linked to, 909–10; in- in bird’s-eye views, 688 Acquaviva, Andrea Matteo (d. -

Revised Final MASTERS THESIS

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Carlo Fontana and the Origins of the Architectural Monograph A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Juliann Rose Walker June 2016 Thesis Committee: Dr. Kristoffer Neville, Chairperson Dr. Jeanette Kohl Dr. Conrad Rudolph Copyright by Juliann Walker 2016 The Thesis of Juliann Rose Walker is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I would first like to start by thanking my committee members. Thank you to my advisor, Kristoffer Neville, who has worked with me for almost four years now as both an undergrad and graduate student; this project was possible because of you. To Jeanette Kohl, who was integral in helping me to outline and finish my first chapter, which made the rest of my thesis writing much easier in comparison. Your constructive comments were instrumental to the clarity and depth of my research, so thank you. And thank you to Conrad Rudolph, for your stern, yet fair, critiques of my writing, which were an invaluable reminder that you can never proofread enough. A special thank you to Malcolm Baker, who offered so much of his time and energy to me in my undergraduate career, and for being a valuable and vast resource of knowledge on early modern European artwork as I researched possible thesis topics. And the warmest of thanks to Alesha Jeanette, who has always left her door open for me to come and talk about anything that was on my mind. I would also like to thank Leigh Gleason at the California Museum of Photography, for giving me the opportunity to intern in collections. -

The Evolution of the Early Refractor 1608 - 1683

The Evolution of the Early Refractor 1608 - 1683 Chris Lord Brayebrook Observatory 2012 Summary The optical workings of the refracting telescope were very poorly understood during the period 1608 thru' the early 1640's, even amongst the cogniscenti. Kepler wrote Dioptrice in the late summer of 1610, but it was not published until a year later, and was not widely read or understood. Lens grinding and polishing techniques traditionally used by spectacle makers were inadequate for manufacturing telescope objectives. Following the pioneering optical work of John Burchard von Schyrle, the artisanship of Johannes Wiesel, and the ingenuity of the Huyghens brothers Constantijn and Christiaan, the refracting telescope was improved sufficiently for resolution limited by atmospheric seeing to be obtained. Not until the phenomenon of dispersion was explained by Isaac Newton could the optical error chromatic aberration be understood. Nevertheless Christiaan Huyghens did design an eyepiece which corrected lateral chromatic aberration, although the theory of his eyepiece was not made known until 1667, and particulars published posthumously in 1703. Introduction This purpose of this paper is to draw together the key elements in the development of the early refractor from 1608 until the early 1680's. During this period grinding and polishing methods of object glasses improved, and several different multi-lens eyepiece arrangements were invented. Those curious about the progress of telescope technology during the C17th, be they researchers, collectors, may find this paper useful. The emergence of the refracting telescope in 1608, so simple a device that it could easily be copied, in all likelyhood had its origins almost two decades beforehand. -

Experience the Greatest Engineering Feat of Renaissance Italy, …

Experience a book that documents the greatest engineering achievement of Renaissance Italy Domenico Fontana, Della Trasportatione dell’Obelisco Vaticano. Rome: D. Basa, 1590. 17 1/8 inches x 11 3/8 inches (435 x 289 mm), 216 pages, including 38 engraved plates. One of the first stops for any visitor to Rome is the oval piazza known as St. Peter’s Square. At the very center, against the imposing backdrop of St. Peter’s Basilica, with its huge façade and its famous dome, an obelisk of pink granite from Egypt perches with surprising lightness on the backs of four miniature bronze lions. It is virtually impossible for us now to imagine the Vatican any other way. In 1585, however, not one piece of this spectacular view had yet been set in place. Carved of Aswan granite in the reign of Nebkaure Amenemhet II (1992– 1985 BC), the obelisk originally stood before the monumental gateway to the Temple of the Sun at Heliopolis. It was brought to Rome in 37 AD by the emperor Caligula as one of many tokens of the Roman conquest of Egypt, and was erected in the Circus of Caligula (later the Circus of Nero). In 1585, Pope Sixtus V announced that he would move the obelisk as part of his master plan for the renovation of the city of Rome. Five hundred contenders thronged to the city to present their plans for the feat, but that of Domenico Fontana seemed to promise the most successful results: Fontana’s huge wooden scaffolding, each leg made of four tree trunks bound together, took the full measure of the granite hulk it was designed to move with gentle precision. -

Giovanni Battista Contini

Giovanni Battista Contini Italian architect of the Late Baroque period (1641-1723) Son of Francesco and Agata Baronio was born in Rome on May 7, 1642. He had the first training of an architect by his father who "nobility educated him and sent to all the schools to which the nobles were subjected", but he also perfected under Gian Lorenzo Bernini. He was so attached to the great master that he would assist him to death and to have a portrait of him "printed on canvas with black frame". The first important commission of CONTINI to be known seems to be the erection of the catafalco for Alexander VII (1667). arrived through Bernini. In Rome, in addition to carrying out practical duties such as those of measuring and architect of the Apostolic Chamber and Architect of the Virgin Water, in which he succeeded Bernini (1681-1723), he dedicated himself particularly to the erection of family chapels and altars; but his main activity soon moved to different places and often far from Rome, and yet in the papal state. Three years after the death of Bemini, in 1683, CONTINI became principal of the Accademia di S. Luca, succeeding Luigi Garzi in a prestigious duty function as indicative of the professional stature he had reached at that time. In the Academy, however, he was disappointed, demonstrating in a way too obvious that his interest focused on practicing the profession. In 1696 he was judged in the banned competition on the occasion of the first centenary of the Academy, but no other activities for this institution were known until 1702, when he worked as an instructor Along with Francesco Fontana, Sebastiano Cipriani, Carlo Buratti and Carlo Francesco Bizzaccheri. -

Mok Tips Compass2016 Marco

Hospitality Aroma compass Dear Guest, The following is not only a list of useful info, but a real personal guide we made for you which contains all the info we think you may need to know before traveling and suggestions to plan your stay. Some of them will be extremely useful during your stay, in terms of how to move around and where to find this or that. In one word, this will be you compass (or compass ). These suggestions are the result of our experience, answering thousands of questions, and our 30+ years of Roman life. We hope you will enjoy reading through it cause our main goal is that you take the most out of your time in Rome. We want your stay in Rome to be as perfect as you dreamt it when you were thinking “let’s go to Rome this year!”. Please count on us for any question you might have, before and during your stay. We look forward to welcome you in Roma, staff How to get to Private Shuttle Service As Rome’s taxi drivers are not the best tourist welcomers , we prefer to offer you our help to book a secure and punctual private shuttle service from the airport or from Civitavecchia Port. Our rates: From/to the airport From/to Civitavecchia Port 1/3 people € 55,00 € 150,00 4 people € 65,00 € 165,00 5 people € 70,00 € 165,00 6 people € 80,00 € 180,00 7 people € 90,00 € 210,00 Please let us know (up to 24hrs. in advance) in case you would like to have a car/van to pick you up. -

064-Sant'andrea Delle Fratte

(064/36) Sant'Andrea delle Fratte Sant'Andrea delle Fratte is a minor basilica, as well as an early 17th century parish, titular and convent church in the rione Colonna, just to the south of the Piazza di Spagna, dedicated to St Andrew the Apostle. History The first church here was built in the 1192, called infra hortes (later translated into "delle Fratte" or "shrubs") for it was located in a countryside area. The first time that the name Fratte is used is in the 15th century. It means literally "woods" or "overgrown vegetation", and seems to commemorate an overgrown area which might have been an abandoned piece of land, some shrubby garden or the facing slope of the Pincian hill when it was still wild. (1) (11) The church was probably rebuilt (or newly built on this site) in the 15th century, when there is a hint in the records that an Augustinian nunnery was established here. Then it was for some time the national church of Scotland as an independent kingdom (St Andrew is Scotland's patron). After the Scottish Reformation in 1560 the Scots completely lost interest in it, and for a while it was taken over by a pious confraternity dedicated to the Blessed Sacrament. However it was given to the Order of Minim of St. Francis of Paola Friars in 1585, and they still serve the parish which was simultaneously created. (1) (11) In 1604 the construction of the new church was begun, under the design of Gaspare Guerra. The project halted in 1612 due to lack of funds. -

The Monastery of Montevergine Its Foundation and Early Development

The Monastery of Montevergine Its Foundation and Early Development (1118-1210) Isabella Laura Bolognese Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History September 2013 ~ i ~ The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Isabella Laura Bolognese to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2013 The University of Leeds and Isabella Laura Bolognese ~ ii ~ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS What follows has been made possible by the support and guidance of a great many scholars, colleagues, family, and friends. I must first of all thank my supervisor, Prof. Graham Loud, who has been an endless source of knowledge, suggestions, criticism, and encouragement, of both the gentle and harsher kind when necessary, throughout the preparation and writing of my PhD, and especially for sharing with me a great deal of his own unpublished material on Cava and translations of primary sources. I must thank also the staff and colleagues at the Institute for Medieval Studies and the School of History, particularly those who read, commented, or made suggestions for my thesis: Dr Emilia Jamroziak and Dr William Flynn have both made important contributions to the writing and editing of this work. -

Ferguson2012.Pdf

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Carlo Emilio Gadda as Catholic and Man of Science: The Case of Quer pasticciaccio brutto de via Merulana Christopher John Ferguson Ph.D The University of Edinburgh 2012 Declaration I declare that this thesis has been composed exclusively by myself, that it is my own work and that no part of it has been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Christopher John Ferguson Stoneyburn, 16 th of May 2012. 2 This thesis is dedicated to my mum, my dad and Sarah. 3 Abstract The present study looks at the influence that two of the major cultural forces of the twentieth century had on the output of Carlo Emilio Gadda. It grew out of a search for ways of discussing Gadda and in particular his 1957 novel Quer pasticciaccio brutto de via Merulana that would be accessible to the widest possible audience. -

Short-Term Study Abroad Program Information

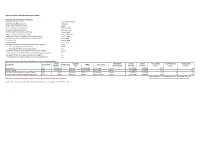

Short-Term Study Abroad Program Information Please provide the following information: Study Abroad Program Name: UGA Classics in Rome Study Abroad (SABD) Course ID: SABD 1107 Study Abroad (SABD) Course CRN: TBD Semester Program will be Offered: Summer 2019 Part of Term (Select Part of Term that most closely aligns with program dates)* : Extended Summer Session Click Here for Part of Term Dates ("Classes Begin" and "Classes End") Program Director/Contact Name: Elena Bianchelli, Chris Gregg Program Director/Contact Phone Number: 706-206-6096, 202-904-3878 Program Director/Contact Email Address: [email protected], [email protected] Program Start Date (First meeting with enrolled students ): 6/2/2019 Program End Date (Last meeting with enrolled students ): 7/11/2019 Travel Start Date: 6/2/2019 Travel End Date: 7/11/2019 Anticipated Number of Total Students Participating in Program: 24 Anticipated Number of UGA Students: 20 Anticipated Number of Transient Students: 4 Anticipated Number of Undergraduate Students in the Program: 20-24 Total Number of Credit Hours Taken by Each Undergraduate Student: 9 Anticipated Number of Graduate Students in the Program: 0-4 Total Number of Credit Hours Taken by Each Graduate Student: 6 Please list each course offered through the program on a separate row below: Schedule Department Course Course Total Lecture Total Field/ Lab Total Contact Course Title Course Prefix Course Number Credit Hours Instructor(s) Type of Instructor(s) Start Date End Date Hours Hours Hours** Ancient Rome CLAS 4350/6350 3 Lecture Chris -

Short-Term Study Abroad Program Information

Short-Term Study Abroad Program Information Please provide the following information: Study Abroad Program Name: UGA Classics in Rome Study Abroad (SABD) Course ID: SABD 1107 Study Abroad (SABD) Course CRN: 54169 Semester Program will be Offered: Summer 2018 Program Director/Contact Name: Elena Bianchelli Program Director/Contact Phone Number: 706 542 8392 Program Director/Contact Email Address: [email protected] Program Start Date (First meeting with enrolled students ): May 27, 2018 Program End Date (Last meeting with enrolled students ): July 5, 2018 Travel Start Date: May 26, 2018 Travel End Date: July 5, 2018 Anticipated Number of Total Students Participating in Program: 15-20 Anticipated Number of UGA Students: 13-17 Anticipated Number of Transient Students: 0-4 Anticipated Number of Undergraduate Students in the Program: 15-20 Total Number of Credit Hours Taken by Each Undergraduate Student: 9 Anticipated Number of Graduate Students in the Program: 0-2 Total Number of Credit Hours Taken by Each Graduate Student: 6 Please list each course offered through the program on a separate row below: Course Schedule Department Course Course Total Lecture Total Field/ Lab Total Contact Course Title Course Prefix Credit Hours CRN(s) Instructor(s) Number Type of Instructor(s) Start Date End Date Hours Hours Hours* Ancient Rome CLAS 4350/6350 3 Lecture 60546/61881 Chris Gregg Classics 5/27/2018 7/5/2018 38.5 7 42 The Art of Rome CLAS 4400/6400 3 Lecture 60547/61882 Chris Gregg Classics 5/27/2018 7/5/2018 37.5 6 40.5 The Urban Tradition of Rome (Selected Topics) CLAS 4305 3 Seminar 60548 Chris Gregg Classics 5/27/2018 7/5/2018 38 6 41 The Latin Tradition of Rome (Advanced Readings) LATN 4405 3 Seminar 61355 Elena Bianchelli Classics 5/27/2018 7/5/2018 37.5 4 39.5 *Total Contact Hours = Total Lecture Hours + (Total Field Hours / 2) Please also complete the Academic Itinerary found on the second worksheet of this document. -

Rome Architecture Guide 2020

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Zone 1: Ancient Rome The Flavium Amphitheatre was built in 80 AD of concrete and stone as the largest amphitheatre in the world. The Colosseum could hold, it is estimated, between 50,000 and 80,000 spectators, and was used The Colosseum or for gladiatorial contests and public spectacles such as mock sea Amphitheatrum ***** Unknown Piazza del Colosseo battles, animal hunts, executions, re-enactments of famous battles, Flavium and dramas based on Classical mythology. General Admission €14, Students €7,5 (includes Colosseum, Foro Romano + Palatino). Hypogeum can be visited with previous reservation (+8€). Mon-Sun (8.30am-1h before sunset) On the western side of the Colosseum, this monumental triple arch was built in AD 315 to celebrate the emperor Constantine's victory over his rival Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (AD 312). Rising to a height of 25m, it's the largest of Rome's surviving ***** Arch of Constantine Unknown Piazza del Colosseo triumphal arches. Above the archways is placed the attic, composed of brickwork revetted (faced) with marble. A staircase within the arch is entered from a door at some height from the ground, on the west side, facing the Palatine Hill. The arch served as the finish line for the marathon athletic event for the 1960 Summer Olympics. The Domus Aurea was a vast landscaped palace built by the Emperor Nero in the heart of ancient Rome after the great fire in 64 AD had destroyed a large part of the city and the aristocratic villas on the Palatine Hill.