Rebuilding the Mental Health System in Iraq in the Context of Transitional Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Evidence-Based Report Analyses from a Public Health Perspective the Health and Environmental Impact of the Previous, Ongoing and Any Future Conflict with Iraq

This evidence-based report analyses from a public health perspective the health and environmental impact of the previous, ongoing and any future conflict with Iraq, It shows that waging war on Iraq would have enormous humanitarian costs, including disaster for the Iraqi population in both the short and long term, and would create enormous harm further afield to combatants and civilians alike. It concludes by summarising alternatives to war. The report is by Medact, an organisation of health professionals that exists to highlight and take action on the health consequences of war, poverty and environmental degradation and other major threats to global health. For many years the organisation has highlighted the impacts of violent conflict and weapons of mass destruction and worked to improve the health of survivors of conflict such as refugees. Medact’s overarching conclusion is that war is a major hazard to health and prevention must always be better than cure. Medact is the UK affiliate of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW) and shares the federation’s core message of strong opposition to a war or military intervention in Iraq. This report, and also an extended version of it with additional references, can be found on Medact’s website www.medact.org and on the website of IPPNW www.ippnw.org. 601 Holloway Road, London N19 4DJ, UK T +44 (0) 20 7272 2020 F +44 (0) 20 7281 5717 E [email protected] website at www.medact.org registered charity no 1081097 collateral damage the health and environmental costs of war on Iraq collateral damage 1 This analysis of the previous, ongoing and likely future conflict with Iraq spells out the potentially enormous humanitarian costs of waging war. -

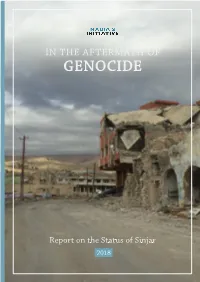

In the Aftermath of Genocide

IN THE AFTERMATH OF GENOCIDE Report on the Status of Sinjar 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS expertise, foremost the Yazidi families who participated in this work, but also a number of other vital contributors: ADVISORY BOARD Nadia Murad, Founder of Nadia’s Initiative Kerry Propper, Executive Board Member of Nadia’s Initiative Elizabeth Schaeffer Brown, Executive Board Member of Nadia’s Initiative Abid Shamdeen, Executive Board Member of Nadia’s Initiative Numerous NGOs, U.N. agencies, and humanitarian aid professionals in Iraq and Kurdistan also provided guidance and feedback for this report. REPORT TEAM Amber Webb, lead researcher/principle author Melanie Baker, data and analytics Kenglin Lai, data and analytics Sulaiman Jameel, survey enumerator co-lead Faris Mishko, survey enumerator co-lead Special thanks to the team at Yazda for assisting with the coordination of this report. L AYOUT AND DESIGN Jens Robert Janke | www.jensrobertjanke.com PHOTOGRAPHY Amber Webb, Jens Robert Janke, and the Yazda Documentation Team. Images should not be reproduced without authorization. reflect those of Nadia’s Initiative. To protect the identities of those who participated in the research, all names have been changed and specific locations withheld. For more information please visit www.nadiasinitiative.org. © FOREWORD n August 3rd, 2014 the world endured yet another genocide. In the hours just before sunrise, my village and many others in the region of Sinjar, O Iraq came under attack by the Islamic State. Tat morning, IS militants began a campaign of ethnic cleansing to eradicate Yazidis from existence. In mere hours, many friends and family members perished before my eyes. Te rest of us, unable to flee, were taken as prisoners and endured unspeakable acts of violence. -

The Status of Women in Iraq: an Assessment of Iraq’S De Jure and De Facto Compliance with International Legal Standards

ILDP Iraq Legal Development Project The Status of Women in Iraq: An Assessment of Iraq’s De Jure and De Facto Compliance with International Legal Standards July 2005 © American Bar Association 2005 The statements and analysis contained herein are the work of the American Bar Association’s Iraq Legal Development Project (ABA/ILDP), which is solely responsible for its content. The Board of Governors of the American Bar Association has neither reviewed nor sanctioned its contents. Accordingly, the views expressed herein should not be construed as representing the policy of the ABA/ILDP. Furthermore, noth- ing contained in this report is to be considered rendering legal advice for specific cases, and readers are responsible for obtaining such advice from their own legal counsel. This publication was made possible through support provided by the U.S. Agency for International Development through the National Demo- cratic Institute. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Agency for International Development. Acknowledgements This Assessment has been prepared through the cooperation of individuals and organizations working throughout Iraq as well as in Amman, Jordan and Washington DC. Many individuals worked tirelessly to make this report thorough, accurate, and truly reflective of the realities in Iraq and its sub-regions. Special mention should be made to the following individuals (in alphabetical order): Authors The ABA wishes to recognize the achievements of the staff of the ABA-Iraq Legal Development Project who authored this report: Kelly Fleck, Sawsan Gharaibeh, Aline Matta and Yasmine Rassam. -

International Protection Considerations with Regard to People Fleeing the Republic of Iraq

International Protection Considerations with Regard to People Fleeing the Republic of Iraq HCR/PC/ May 2019 HCR/PC/IRQ/2019/05 _Rev.2. INTERNATIONAL PROTECTION CONSIDERATIONS WITH REGARD TO PEOPLE FLEEING THE REPUBLIC OF IRAQ Table of Contents I. Executive Summary .......................................................................................... 6 1) Refugee Protection under the 1951 Convention Criteria and Main Categories of Claim .... 6 2) Broader UNHCR Mandate Criteria, Regional Instruments and Complementary Forms of Protection ............................................................................................................................. 7 3) Internal Flight or Relocation Alternative (IFA/IRA) .............................................................. 7 4) Exclusion Considerations .................................................................................................... 8 5) Position on Forced Returns ................................................................................................. 9 II. Main Developments in Iraq since 2017 ............................................................. 9 A. Political Developments ........................................................................................................... 9 1) May 2018 Parliamentary Elections ...................................................................................... 9 2) September 2018 Kurdistan Parliamentary Elections ......................................................... 10 3) October 2017 Independence -

Health Costs of the Gulfwar

Health costs of the Gulf war BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.303.6797.303 on 3 August 1991. Downloaded from Ian Lee, Andy Haines Although much has been written about the Gulf caused 13 deaths, 200 injuries, and damage to 4000 conflict, comparatively little attention has been paid to buildings.6 the medical aspects of the conflict and to the overall American and allied aircraft averaged 2500 combat balance between the costs and benefits. As the situation sorties daily, including more than 1000 bombing continues to evolve in Iraq it becomes clearer that some missions a day. Airforce Secretary Donald Rice said of the short term effects of the war given so much that air to ground strikes were roughly 1% of the publicity will be overshadowed by the medium and bombs that were dropped in Vietnam from 1961-72 long term adverse consequences. The overall balance (6-2 million tons). Nevertheless, the rate of tonnage between the costs and benefits ofwar has to be assessed dropped (63 000 tons per month in the Gulf war) was in terms of its impact on human health, human rights, more than that in the Vietnam war (34 000 tons per the environment, the economy, and the long term month) or the Korean war (22 000 tons per month).' political balance in the region. This paper considers Air power paralysed Iraq strategically, operationally, primarily the impacts on health but also touches on and tactically. The contrast between detailed figures other fields. of bombs dropped and exact quantities of military material destroyed but nebulous estimates of human casualties is striking. -

Original Article

ORIGINAL RESEARCH Health and Health Seeking in Mosul During ISIS Control and Liberation: Results From a 40-Cluster Household Survey Riyadh Lafta, MD, PhD; Valeria Cetorelli, PhD; Gilbert Burnham, MD, PhD ABSTRACT Objectives: ISIS seized Mosul in June 2014. This survey was conducted to assess health status, health needs, and health-seeking behavior during ISIS control and the subsequent Iraqi military campaign. Methods: Forty clusters were chosen: 25 from east Mosul and 15 from west Mosul. In each, 30 households were interviewed, representing 7559 persons. The start house for each cluster was selected using satellite maps. The survey in east Mosul was conducted from March 13–31, 2017, and in west Mosul from July 18–31, 2017. Results: In the preceding 2 weeks, 265 (5.4%) adults reported being ill. Some 67 (25.3%) complaints were for emotional or behavioral issues, and 59 (22.3%) for noncommunicable diseases. There were 349 (13.2%) children under age 15 reportedly ill during this time. Diarrhea, respiratory complaints, and emotional and behavioral problems were most common. Care seeking among both children and adults was low, especially in west Mosul. During ISIS occupation, 640 (39.0%) women of childbearing age reported deliveries. Of these, 431 (67.3%) had received some antenatal care, and 582 (90.9%) delivered in a hospital. Complications were reported by 417 (65.2%). Conclusions: Communicable and noncommunicable diseases were reported for both children and adults, with a high prevalence of emotional and behavioral problems, particularly in west Mosul. Care-seeking was low, treatment compliance for noncommunicable diseases was poor, and treatment options for patients were limited. -

Humanitarian Implications of the Wars in Iraq Nasir Ahmed Al Samaraie Nasir Ahmed Al Samaraie Is a Former Ambassador at the Iraqi Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Volume 89 Number 868 December 2007 Humanitarian implications of the wars in Iraq Nasir Ahmed Al Samaraie Nasir Ahmed Al Samaraie is a former ambassador at the Iraqi Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Abstract The current situation in Iraq could be described as a ‘‘war on civilians’’, for it mainly affects the livelihood and well-being of the civilian population, while serious security problems prevent the Iraqi people from leading a normal life. Going beyond the direct victims of the conflict, this article deals with the daily problems faced by Iraqi society, namely the lack of security in terms of housing, education and health care, as well as protection for the more vulnerable such as women and children. The forcible eviction of many Iraqis is, however, the main problem threatening the basic cohesion of Iraqi society. A country of rich diversity Iraq is a country of rich diversity that goes far back in history. Its current social and political structure has its roots in Mesopotamia, a land of tribal, religious and evolving cultural interaction for more than seven thousand years. Settlement in Mesopotamia began around 6500 BC and represents the nucleus of the present Iraqi nation.1 Naturally those settlements were first established on the banks of rivers or close to other natural resources, where people had easy access to water and open land that provided food for them and their animals. The eventual growth of these settlements into primitive communities coincided with the emergence of a number of ruling powers in that area, ranging from local to regional and continental dynasties. -

Health and Welfare in Iraq After the Gulf Crisis an in -Depth Assessment

HEALTH AND WELFARE IN IRAQ AFTER THE GULF CRISIS AN IN-DEPTH ASSESSMENT International Study Team October 1991 HEALTH AND WELFARE IN IRAQ AFTER THE GULF CRISIS AN IN -DEPTH ASSESSMENT From August 23 to September 5, the International Study Team on the Gulf Crisis comprehensively surveyed the impact of the Gulf Crisis on the health and welfare of the Iraqi population. The Team consisted of eighty-seven researchers drawn from a wide variety of disciplines, including agriculture, electrical engineering, environmental sciences, medicine, economics, child psychology, sociology, and public health. Team members visited Iraq’s thirty largest cities in all eighteen Governorates, including rural areas in every part of the country. The mission was accomplished without Iraqi government interference or supervision. Principal funding was supplied by UNICEF, the MacArthur Foundation, the John Merck Fund, and Oxfam- UK. The study team has prepared separate in-depth reports on the Gulf Crisis and its impact on Iraqi civilians focused on the following subjects: 1. Child Mortality and Nutrition Survey 2. Health Facilities Survey 3. Electrical Facilities Survey 4. Water and Wastewater Systems Survey 5. Environmental and Agricultural Survey 6. Income and Economic Survey 7. Child Psychology Survey 8. Women Survey This statement summarizes the principal findings of the research. Individual project reports, representing the findings and views of individual authors, are available for more detailed information. The economic and social disruption and destruction caused by the Gulf Crisis has had a direct impact on the health conditions of the children in Iraq. Iraq desperately needs not only food and medicine, but also spare parts to repair basic infrastructure in electrical power generation, water purification, and sewage treatment. -

Health Services in Iraq

Review Health services in Iraq Thamer Kadum Al Hilfi , Riyadh Lafta, Gilbert Burnham After decades of war, sanctions, and occupation, Iraq’s health services are struggling to regain lost momentum. Many Lancet 2013; 381: 939–48 skilled health workers have moved to other countries, and young graduates continue to leave. In spite of much See Editorial page 875 rebuilding, health infrastructure is not fully restored. National development plans call for a realignment of the health See Comment page 877 system with primary health care as the basis. Yet the health-care system continues to be centralised and focused on Department of Community hospitals. These development plans also call for the introduction of private health care as a major force in the health Medicine, Al Kindy College of sector, but much needs to be done before policies to support this change are in place. New initiatives include an active Medicine, Baghdad, Iraq (Prof T K Al Hilfi MBChB); programme to match access to health services with the location and needs of the population. Department of Community Medicine, Al Munstansiriya Introduction was augmented by immigration of doctors and nurses University, Baghdad, Iraq In this Review, we aim to provide an appreciation of the fl eeing from else where in Iraq.15 (Prof R Lafta MBChB); and Department of International health status of Iraqis, the function of Iraq’s health system, In May, 2006, Nouri al-Maliki became the Prime Minister Health, The Johns Hopkins 16 the rapid changes occurring in the health sector, and the of Iraq. British troops left Iraq in 2009; the last US forces Bloomberg School of Public need for improved policies to guide these processes. -

Iraqi Refugees in Syria

The Brookings Institution—University of Bern Project on Internal Displacement Iraqi Refugees in the Syrian Arab Republic: A Field-Based Snapshot by Ashraf al-Khalidi, Sophia Hoffmann and Victor Tanner An Occasional Paper June 2007 Iraqi Refugees in the Syrian Arab Republic: A Field-Based Snapshot by Ashraf al-Khalidi, Sophia Hoffmann and Victor Tanner THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION – UNIVERSITY OF BERN PROJECT ON INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Washington DC 20036-2188 TELEPHONE: +1 (202) 797-6168 FAX: +1 (202) 797-2970 EMAIL: [email protected] www.brookings.edu/idp This study was supported in part by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). However, the views and opinions presented in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of UNHCR. I went to the House of God and returned, Yet I found nothing like my home. ∗ - Iraqi proverb ∗ The ‘House of God’ refers to the Ka‘ba, the holy shrine in Mecca. About the Authors Ashraf al-Khalidi is the pseudonym of an Iraqi researcher and civil society activist based in Baghdad. Mr. Khalidi has worked with civil society groups from nearly all parts of Iraq since the first days that followed the overthrow of the regime of Saddam Hussein. His contacts within Iraqi society continue to span the various sectarian divides. He publishes under this pseudonym out of concern for his safety. He is the author, with Victor Tanner, of “Sectarian Violence: Radical Groups Drive Internal Displacement in Iraq,” a Brookings occasional paper (October 2006). Sophia Hoffmann is a German researcher based in London who specializes in Middle Eastern affairs. -

Iraq-A Multifaceted Emergency Chang

IRAQ – HEALTH ASPECTS OF A MULTI-FACETED EMERGENCY Dr Rae-Wen Chang - Jan 2007 Introduction: the human landscape of Iraq History, they say, is written by the victor. In the case of the current conflict in Iraq, posterity may declare no victors but read a bloody tale of combatants and civilian victims. As Robert Fisk comments: “War is primarily not about victory or defeat but about death and the infliction of death. It represents the total failure of the human spirit” (2006, p.xix). It is imperative to examine the factors that have led to chaos in the land known as Mesopotamia, the cradle of civilisation (Braude 2003). The abysmal health conditions in the country today are a reflection of the political struggles that have taken place in Iraq over the past 18 years; soaring child and maternal mortality and malnutrition flag a country in crisis. The true death toll is unknown after years of conflict. Lack of co-ordinated international aid efforts has forced questions of politicisation of humanitarian aid and highlighted reconstruction failures. Health workers face unprecedented levels of danger whilst trying to do their job; rather than an emblem for protection, the red cross signifies a high-value target. The prickly issue of military medicos has come under fire with reports of human rights abuses in Abu Ghraib prison. The ultimate aim should be to bring back the people of Iraq to reconstruct their lives and aspire to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person. Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services. -

Iraq HUMAN at a Crossroads RIGHTS Human Rights in Iraq Eight Years After the US-Led Invasion WATCH

Iraq HUMAN At a Crossroads RIGHTS Human Rights in Iraq Eight Years after the US-Led Invasion WATCH At a Crossroads Human Rights in Iraq Eight Years after the US-Led Invasion Copyright © 2010 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-736-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org February 2011 1-56432-736-1 At a Crossroads Human Rights in Iraq Eight Years after the US-Led Invasion Summary .................................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. 5 I. Rights of Women and Girls ...................................................................................................... 6 Background .......................................................................................................................... 6 Targeting Female Leaders and Activists ..............................................................................