Rebecca Bearce New 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

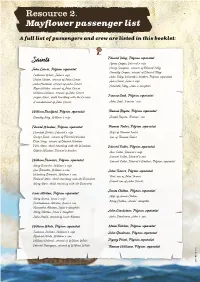

Resource 2 Mayflower Passenger List

Resource 2. Mayflower passenger list A full list of passengers and crew are listed in this booklet: Edward Tilley, Pilgrim separatist Saints Agnus Cooper, Edward’s wife John Carver, Pilgrim separatist Henry Sampson, servant of Edward Tilley Humility Cooper, servant of Edward Tilley Catherine White, John’s wife John Tilley, Edwards’s brother, Pilgrim separatist Desire Minter, servant of John Carver Joan Hurst, John’s wife John Howland, servant of John Carver Elizabeth Tilley, John’s daughter Roger Wilder, servant of John Carver William Latham, servant of John Carver Jasper More, child travelling with the Carvers Francis Cook, Pilgrim separatist A maidservant of John Carver John Cook, Francis’ son William Bradford, Pilgrim separatist Thomas Rogers, Pilgrim separatist Dorothy May, William’s wife Joseph Rogers, Thomas’ son Edward Winslow, Pilgrim separatist Thomas Tinker, Pilgrim separatist Elizabeth Barker, Edward’s wife Wife of Thomas Tinker George Soule, servant of Edward Winslow Son of Thomas Tinker Elias Story, servant of Edward Winslow Ellen More, child travelling with the Winslows Edward Fuller, Pilgrim separatist Gilbert Winslow, Edward’s brother Ann Fuller, Edward’s wife Samuel Fuller, Edward’s son William Brewster, Pilgrim separatist Samuel Fuller, Edward’s Brother, Pilgrim separatist Mary Brewster, William’s wife Love Brewster, William’s son John Turner, Pilgrim separatist Wrestling Brewster, William’s son First son of John Turner Richard More, child travelling with the Brewsters Second son of John Turner Mary More, child travelling -

Francis Billington

Francis Billington: Mayflower passenger The names of those which came over first, in the year 1620, and were by the blessing of God the first beginners and in a sort the foundation of all the Plantations and Colonies in New England ; and their families... "John Billington and Ellen his wife, and two sons, John and Francis." William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation 1620-1647, ed. Samuel Eliot Morison (New York: Knopf, 1991), p. 441-3. "The fifth day [of December, 1620] we, through God's mercy, escaped a great danger by the foolishness of a boy, one of ...Billington's sons, who, in his father's absence, had got gunpowder, and had shot off a piece or two, and made squibs; but there being a fowling-piece charged in his father's cabin, shot her off in the cabin; there being a little barrel of [gun] powder half full, scattered in and about the cabin, the fire being within four foot of the bed between the decks, and many flints and iron things about the cabin, and many people about the fire; and yet, by God's mercy, no harm done." Mourt's Relation, ed. Jordan D. Fiore (Plymouth, Mass.: Plymouth Rock Foundation), 1985, p. 27. Francis Billington and the early exploration and settlement of Plymouth "Monday, the eighth day of January ... This day Francis Billington, having the week before seen from the top of a tree on a high hill a great sea [known today as Billington Sea, actually a large pond], as he thought, went with one of the master's mates to see it. -

MAYFLOWER RESEARCH HANDOUT by John D Beatty, CG

MAYFLOWER RESEARCH HANDOUT By John D Beatty, CG® The Twenty-four Pilgrims/Couples on Mayflower Who Left Descendants John Alden, cooper, b. c. 1599; d. 12 Sep. 1687, Duxbury; m. Priscilla Mullins, daughter of William. Isaac Allerton, merchant, b. c. 1587, East Bergolt, Sussex; d. bef. 12 Feb. 1658/9, New Haven, CT; m. Mary Norris, who d. 25 Feb. 1620/1, Plymouth. John Billington, b. by 1579, Spalding, Lincolnshire; hanged Sep. 1630, Plymouth; m. Elinor (__). William Bradford, fustian worker, governor, b. 1589/90, Austerfield, Yorkshire; d. 9 May 1657, Plymouth; m. Dorothy May, drowned, Provincetown Harbor, 7 Dec. 1620. William Brewster, postmaster, publisher, elder, b. by 1567; d. 10 Apr. 1644, Duxbury; m. Mary (__). Peter Brown, b. Jan. 1594/5, Dorking, Surrey; d. bef. 10 Oct. 1633, Plymouth. James Chilton, tailor, b. c. 1556; d. 8 Dec 1620, Plymouth; m. (wife’s name unknown). Francis Cooke, woolcomber, b. c. 1583; d. 7 Apr. 1663, Plymouth; m. Hester Mayhieu. Edward Doty, servant, b. by 1599; d. 23 Aug. 1655, Plymouth. Francis Eaton, carpenter, b. 1596, Bristol; d. bef. 8 Nov. 1633, Plymouth. Moses Fletcher, blacksmith, b. by 1564, Sandwich, Kent; d. early 1621, Plymouth. Edward Fuller, b. 1575, Redenhall, Norfolk; d. early 1621, Plymouth; m. (wife unknown). Samuel Fuller, surgeon, b. 1580, Redenhall, Norfolk; d. bef. 28 Oct. 1633, Plymouth; m. Bridget Lee. Stephen Hopkins, merchant, b. 1581, Upper Clatford, Hampshire; d. bef. 17 Jul. 1644, Plymouth; m. (10 Mary Kent (d. England); (2) Elizabeth Fisher, d. Plymouth, 1640s. John Howland, servant, b. by 1599, Fenstanton, Huntingdonshire; d. -

New England‟S Memorial

© 2009, MayflowerHistory.com. All Rights Reserved. New England‟s Memorial: Or, A BRIEF RELATION OF THE MOST MEMORABLE AND REMARKABLE PASSAGES OF THE PROVIDENCE OF GOD, MANIFESTED TO THE PLANTERS OF NEW ENGLAND IN AMERICA: WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE FIRST COLONY THEREOF, CALLED NEW PLYMOUTH. AS ALSO A NOMINATION OF DIVERS OF THE MOST EMINENT INSTRUMENTS DECEASED, BOTH OF CHURCH AND COMMONWEALTH, IMPROVED IN THE FIRST BEGINNING AND AFTER PROGRESS OF SUNDRY OF THE RESPECTIVE JURISDICTIONS IN THOSE PARTS; IN REFERENCE UNTO SUNDRY EXEMPLARY PASSAGES OF THEIR LIVES, AND THE TIME OF THEIR DEATH. Published for the use and benefit of present and future generations, BY NATHANIEL MORTON, SECRETARY TO THE COURT, FOR THE JURISDICTION OF NEW PLYMOUTH. Deut. xxxii. 10.—He found him in a desert land, in the waste howling wilderness he led him about; he instructed him, he kept him as the apple of his eye. Jer. ii. 2,3.—I remember thee, the kindness of thy youth, the love of thine espousals, when thou wentest after me in the wilderness, in the land that was not sown, etc. Deut. viii. 2,16.—And thou shalt remember all the way which the Lord thy God led thee this forty years in the wilderness, etc. CAMBRIDGE: PRINTED BY S.G. and M.J. FOR JOHN USHER OF BOSTON. 1669. © 2009, MayflowerHistory.com. All Rights Reserved. TO THE RIGHT WORSHIPFUL, THOMAS PRENCE, ESQ., GOVERNOR OF THE JURISDICTION OF NEW PLYMOUTH; WITH THE WORSHIPFUL, THE MAGISTRATES, HIS ASSISTANTS IN THE SAID GOVERNMENT: N.M. wisheth Peace and Prosperity in this life, and Eternal Happiness in that which is to come. -

The Legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1987 The legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony Michael J. Puglisi College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Puglisi, Michael J., "The legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony" (1987). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623769. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-f5eh-p644 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or as a 17”x 23” black and white photographic print. -

Massasoit of The

OUSAMEQUIN “YELLOW FEATHER” — THE MASSASOIT OF THE 1 WAMPANOAG (THOSE OF THE DAWN) “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY 1. Massasoit is not a personal name but a title, translating roughly as “The Shahanshah.” Like most native American men of the period, he had a number of personal names. Among these were Ousamequin or “Yellow Feather,” and Wasamegin. He was not only the sachem of the Pokanoket of the Mount Hope peninsula of Narragansett Bay, now Bristol and nearby Warren, Rhode Island, but also the grand sachem or Massasoit of the entire Wampanoag people. The other seven Wampanoag sagamores had all made their submissions to him, so that his influence extended to all the eastern shore of Narragansett Bay, all of Cape Cod, Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard, and the Elizabeth islands. His subordinates led the peoples of what is now Middleboro (the Nemasket), the peoples of what is now Tiverton (the Pocasset), and the peoples of what is now Little Compton (the Sakonnet). The other side of the Narragansett Bay was controlled by Narragansett sachems. HDT WHAT? INDEX THE MASSASOIT OUSAMEQUIN “YELLOW FEATHER” 1565 It would have been at about this point that Canonicus would have been born, the 1st son of the union of the son and daughter of the Narragansett headman Tashtassuck. Such a birth in that culture was considered auspicious, so we may anticipate that this infant will grow up to be a Very Important Person. Canonicus’s principle place of residence was on an island near the present Cocumcussoc of Jamestown and Wickford, Rhode Island. -

Physical Accomplishment, Spiritual Power, and Indian Masculinity in Early-Seventeenth-Century New England

Ethnohistory ‘‘Ranging Foresters’’ and ‘‘Women-Like Men’’: Physical Accomplishment, Spiritual Power, and Indian Masculinity in Early-Seventeenth-Century New England R. Todd Romero, University of Houston Abstract. Through an examination of seventeenth-century English sources and later Indian folklore, this article illustrates the centrality of religion to defining mascu- linity among Algonquian-speaking Indians in southern New England. Manly ideals were represented in the physical and spiritual excellence of individual living men like the Penacook sachem-powwow Passaconaway and supernatural entities like Maushop. For men throughout the region, cultivating and maintaining spiritual associations was essential to success in the arenas of life defining Indian mascu- linity: games, hunting, warfare, governance, and marriage. As is stressed through- out the essay, masculinity was also juxtaposed with femininity in a number of important ways in Indian society. In seventeenth-century New England, colonial observers often derided In- dian men, contending that ‘‘these ranging foresters,’’ as William Wood once termed them, failed to work and act as men should and offered a potentially dangerous example to the disorderly elements of Anglo-American society. In a typical seventeenth-century English assessment of Indian gender roles, Wood claimed that Indian wives were ‘‘more loving, pitiful, and modest, mild, provident, and laborious than their lazy husbands.’’1 Examining these conceits, scholars have often stressed that such views tell us more about English gender ideals than they reveal about the structure of Indian society. Correctly casting the English hostility toward male Indian gender roles as ethnocentric bias, such work takes special pains to stress the comparative egalitarianism of Native American gender relations. -

Vital Allies: the Colonial Militia's Use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2011 Vital allies: The colonial militia's use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676 Shawn Eric Pirelli University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Pirelli, Shawn Eric, "Vital allies: The colonial militia's use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676" (2011). Master's Theses and Capstones. 146. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/146 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VITAL ALLIES: THE COLONIAL MILITIA'S USE OF iNDIANS IN KING PHILIP'S WAR, 1675-1676 By Shawn Eric Pirelli BA, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2008 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In History May, 2011 UMI Number: 1498967 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 1498967 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. -

Alyson J. Fink

PSYCHOLOGICAL CONQUEST: PILGRIMS, INDIANS AND THE PLAGUE OF 1616-1618 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAW AI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN mSTORY MAY 2008 By Alyson J. Fink Thesis Committee: Richard C. Rath, Chairperson Marcus Daniel Margot A. Henriksen Richard L. Rapson We certify that we have read this thesis and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. THESIS COMMITIEE ~J;~e K~ • ii ABSTRACT In New England effects of the plague of 1616 to 1618 were felt by the Wampanoags, Massachusetts and Nausets on Cape Cod. On the other hand, the Narragansetts were not affiicted by the same plague. Thus they are a strong exemplar of how an Indian nation, not affected by disease and the psychological implications of it, reacted to settlement. This example, when contrasted with that of the Wampanoags and Massachusetts proves that one nation with no experience of death caused by disease reacted aggressively towards other nations and the Pilgrims, while nations fearful after the epidemic reacted amicably towards the Pilgrims. Therefore showing that the plague produced short-term rates of population decline which then caused significant psychological effects to develop and shape human interaction. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................... .iii List of Tables ...........................................................................................v -

•Œa Country Wonderfully Prepared for Their Entertainmentâ•Š The

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council --Online Archive National Collegiate Honors Council Spring 2003 “A Country Wonderfully Prepared for their Entertainment” The Aftermath of the New England Indian Epidemic of 1616 Matthew Kruer University of Arizona, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nchcjournal Part of the Higher Education Administration Commons Kruer, Matthew, "“A Country Wonderfully Prepared for their Entertainment” The Aftermath of the New England Indian Epidemic of 1616" (2003). Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council --Online Archive. 129. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nchcjournal/129 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Collegiate Honors Council at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council --Online Archive by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. MATTHEW KRUER “A Country Wonderfully Prepared for their Entertainment” The Aftermath of the New England Indian Epidemic of 1616 MATTHEW KRUER UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA formidable mythology has grown up around the Pilgrims and their voyage to Athe New World. In the popular myth a group of idealistic religious reformers fled persecution into the wilds of the New World, braving seas, storms, winter, hunger, and death at the hands of teeming hordes of Indians, carving a new life out of an unspoiled wilderness, building a civilization with naked force of will and an unshakable religious vision. As with most historical myths, this account has been idealized to the point that it obscures the facts of the Pilgrims’ voyage. -

CHILDREN on the MAYFLOWER by Ruth Godfrey Donovan

CHILDREN ON THE MAYFLOWER by Ruth Godfrey Donovan The "Mayflower" sailed from Plymouth, England, September 6, 1620, with 102 people aboard. Among the passengers standing at the rail, waving good-bye to relatives and friends, were at least thirty children. They ranged in age from Samuel Eaton, a babe in arms, to Mary Chilton and Constance Hopkins, fifteen years old. They were brought aboard for different reasons. Some of their parents or guardians were seeking religious freedom. Others were searching for a better life than they had in England or Holland. Some of the children were there as servants. Every one of the youngsters survived the strenuous voyage of three months. As the "Mayflower" made its way across the Atlantic, perhaps they frolicked and played on the decks during clear days. They must have clung to their mothers' skirts during the fierce gales the ship encountered on other days. Some of their names sound odd today. There were eight-year-old Humility Cooper, six-year-old Wrestling Brewster, and nine-year-old Love Brewster. Resolved White was five, while Damans Hopkins was only three. Other names sound more familiar. Among the eight-year- olds were John Cooke and Francis Billington. John Billington, Jr. was six years old as was Joseph Mullins. Richard More was seven years old and Samuel Fuller was four. Mary Allerton, who was destined to outlive all others aboard, was also four. She lived to the age of eighty-three. The Billington boys were the mischief-makers. Evidently weary of the everyday pastimes, Francis and John, Jr. -

JOHN BILLINGTON of the MAYFLOWER Which Child Of

JOHN BILLINGTON OF THE MAYFLOWER Among those on board the ship Mayflower when it finally arrived in New England in November, 1620 was John Billington. He was born in England about 1579 and married Ellinor (----). John died by hanging in Plymouth Colony in September, 1630, after he was convicted of murdering John Newcomen. This was the only hanging in the early history of the Colony. Usually the penalty was confinement to the stocks, a structure which locked the hands and head in an uncomfortable position in public view. His wife Ellinor slandered a Plymouth man, and she was sentenced to sit in the stocks and be whipped. John was a strong supporter of the revolt against Governor Bradford. He and his sons John and Francis often got into trouble during the first decade of the colony’s existence. While the Mayflower was anchored off Cape Cod, Francis Billington fired a musket on board the ship . According to tradition, Francis climbed a tree soon after arrival in Plymouth and spotted what he called a "great sea," believing it to be the Pacific Ocean. He and one of the Mayflower's crew members went to explore the sea, but became alarmed when they saw some abandoned Native American houses. They were alone with only a single gun. In memory of Billington's error, the pond was called "Billington's Sea.” And son John did his share of mischief as well. In 1621, he wandered off and went missing for five days. Native Americans from Nauset eventually found him. The Pilgrims left to intervene, but John was returned peaceably without any threat of war or attack.