Documents Acquired by ERIC Include Any.Inforial Unpublished * Materials Not Available from Other Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Film and Video Archive

Department of Film and Video archive, Title Department of Film and Video archive (fv001) Dates 1907-2009 [bulk 1970-2003] Creator Summary Quantity 200 linear feet of graphic material and textual records Restrictions on Access Language English Kate Barbera PDF Created January 20, 2016 Department of Film and Video archive, Page 2 of 65 Carnegie Museum of Art (CMOA) established the Film Section (subsequently, the Section of Film and Video and the Department of Film and Video) in 1970, making it one of the first museum-based film departments in the country. As part of the first wave of museums to celebrate moving image work, CMOA played a central role in legitimizing film as an art form, leading a movement that would eventually result in the integration of moving image artworks in museum collections worldwide. The department's active roster of programmingÐfeaturing historical screenings, director's retrospectives, and monthly appearances by experimental filmmakers from around the worldÐwas a leading factor in Pittsburgh's emergence in the 1970s as ªone of the most vibrant and exciting places in America for exploring cinema.º (Robert A. Haller, Crossroads: Avant-garde Film in Pittsburgh in the 1970s, 2005). The museum also served as a galvanizing force in the burgeoning field by increasing visibility and promoting the professionalization of moving image art through its publication of Film and Video Makers Travel Sheet (a monthly newsletter distributed to 2,000 subscribers worldwide) and the Film and Video Makers Directory (a listing of those involved in film and video production and exhibition) and by paying substantial honoraria to visiting filmmakers. -

Une Bibliographie Commentée En Temps Réel : L'art De La Performance

Une bibliographie commentée en temps réel : l’art de la performance au Québec et au Canada An Annotated Bibliography in Real Time : Performance Art in Quebec and Canada 2019 3e édition | 3rd Edition Barbara Clausen, Jade Boivin, Emmanuelle Choquette Éditions Artexte Dépôt légal, novembre 2019 Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec Bibliothèque et Archives du Canada. ISBN : 978-2-923045-36-8 i Résumé | Abstract 2017 I. UNE BIBLIOGraPHIE COMMENTÉE 351 Volet III 1.11– 15.12. 2017 I. AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGraPHY Lire la performance. Une exposition (1914-2019) de recherche et une série de discussions et de projections A B C D E F G H I Part III 1.11– 15.12. 2017 Reading Performance. A Research J K L M N O P Q R Exhibition and a Series of Discussions and Screenings S T U V W X Y Z Artexte, Montréal 321 Sites Web | Websites Geneviève Marcil 368 Des écrits sur la performance à la II. DOCUMENTATION 2015 | 2017 | 2019 performativité de l’écrit 369 From Writings on Performance to 2015 Writing as Performance Barbara Clausen. Emmanuelle Choquette 325 Discours en mouvement 370 Lieux et espaces de la recherche 328 Discourse in Motion 371 Research: Sites and Spaces 331 Volet I 30.4. – 20.6.2015 | Volet II 3.9 – Jade Boivin 24.10.201 372 La vidéo comme lieu Une bibliographie commentée en d’une mise en récit de soi temps réel : l’art de la performance au 374 Narrative of the Self in Video Art Québec et au Canada. Une exposition et une série de 2019 conférences Part I 30.4. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Punk Aesthetics in Independent "New Folk", 1990-2008

PUNK AESTHETICS IN INDEPENDENT "NEW FOLK", 1990-2008 John Encarnacao Student No. 10388041 Master of Arts in Humanities and Social Sciences University of Technology, Sydney 2009 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Tony Mitchell for his suggestions for reading towards this thesis (particularly for pointing me towards Webb) and for his reading of, and feedback on, various drafts and nascent versions presented at conferences. Collin Chua was also very helpful during a period when Tony was on leave; thank you, Collin. Tony Mitchell and Kim Poole read the final draft of the thesis and provided some valuable and timely feedback. Cheers. Ian Collinson, Michelle Phillipov and Diana Springford each recommended readings; Zac Dadic sent some hard to find recordings to me from interstate; Andrew Khedoori offered me a show at 2SER-FM, where I learnt about some of the artists in this study, and where I had the good fortune to interview Dawn McCarthy; and Brendan Smyly and Diana Blom are valued colleagues of mine at University of Western Sydney who have consistently been up for robust discussions of research matters. Many thanks to you all. My friend Stephen Creswell’s amazing record collection has been readily available to me and has proved an invaluable resource. A hearty thanks! And most significant has been the support of my partner Zoë. Thanks and love to you for the many ways you helped to create a space where this research might take place. John Encarnacao 18 March 2009 iii Table of Contents Abstract vi I: Introduction 1 Frames -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

Cat Estambul.Pdf

2 3 GOYA ZAMANININ TANIĞI Gravürler ve Resimler GOYA WITNESS OF HIS TIME Engravings and Paintings Sergi Kataloğu Exhibition Catalogue Pera Müzesi Yayını Pera Museum Publication 55 İstanbul, Nisan April 2012 ISBN:........................... Küratörler Curators: Marisa Oropesa Maria Toral Yayına Hazırlayanlar Editors: Witness of Teşekkürler Acknowledgements: Zamanının Tanığı Begüm Akkoyunlu Ersöz Tania Bahar Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao His Time Soprintendenza Speciale per il Polo Museale Fiorentino, Gravürler ve Resimler Yayın Koordinatörü Publication Coordinator: Galleria degli Uffizi Zeynep Ögel Fundación de Santamarca y de San Ramón y San Antonio Engravings Fundación Zuloaga Proje Asistanı Project Assistant: Colección Joaquín Rivero Selin Turam and Paintings Miriam Alzuri Çeviriler Translations: Placido Arango Lucia Cabezón İspanyolca-Türkçe Spanish-Turkish Valentina Conticelli Roza Hakmen Teresa García Iban Çiğdem Öztürk Anna Gamazo Adolfo Lafuente Guantes İspanyolca-İngilizce Spanish-English Vanessa Mérida Alphabet Traducciones Fernando Molina López Antonio Natali İtalyanca-Türkçe Italian-Turkish Ignacio Olmos Kemal Atakay Marilyn Orozco José Remington İtalyanca-İngilizce Italian-English Helena Rivero Spaziolingue Milan Margarita Ruyra Ana Sánchez Lassa Türkçe Düzelti Turkish Proofreading: Ignacio Suarez-Zuloaga Müge Karalom Laura Trevijano Grafik Tasarım Graphic Design: Instituto Cervantes, Madrid TUT Ajans, www.tutajans.com Víctor García de la Concha, Montserrat Iglesias Santos, Juana Escudero Méndez, Ernesto Pérez Zúñiga, María -

David Askevold

Pop culture BOOK RELEASE ISBN 13: 978‐0‐86492‐659‐3 hc $50 / 144 pp / 8.5 x 10.5 David Askevold Pub Date: September 2011 (Canada & U.S.) Goose Lane Editions and Art Gallery of Nova Scotia Once Upon a Time in the East Edited by David Diviney David Askevold broke into the art scene when his work was included in the seminal exhibition Information at New York’s MOMA 1970, helping cement Conceptualism as a genre. He later became recognized as one of the most important contributors to the development and pedagogy of conceptual art; his work has been included in many of the genre’s formative texts and exhibitions. David Askevold: Once Upon a Time in the East takes readers on an eclectic journey through the various strains of Askevold’s pioneering practice — sculpture and installation, film and video, photography and photo‐text works, and digital imagery. David Askevold moved from Kansas City to Halifax in 1968 to lecture at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. During the early 1970s, his famous Projects Class brought such artists as Sol Lewitt, Vito Acconci, John Baldessari, Dan Graham, and Lawrence Weiner to work with his students, focusing critical attention on his adopted city and on his own unorthodox approach to making art. He quickly became one of the most important conceptual artists practicing in Canada, and throughout his career, he remained at the vanguard of contemporary practice. David Askevold: Once Upon a Time in the East features essays by celebrated writer‐curators Ray Cronin, Peggy Gale, Richard Hertz (author of The Beat and the Buzz), and Irene Tsatsos, as well Askevold’s contemporaries including Aaron Brewer, Tony Oursler, and Mario Garcia Torres. -

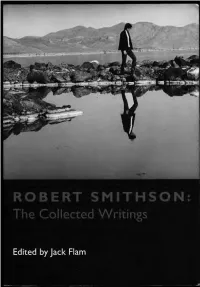

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

Video Circuits

"Written on top of ments at VIDEO CIRCUITS DECEMBER 4 - JANUARY 2, 1974 McLAUGHLIN LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH Preface and Acknowledgements This exhibition grew out of a mutual interest in video tape as an art form shared by Eric Cameron, Professor of Fine Art, Ian Easterbrook and Noel Harding of the Television Unit, Audio Visual Services at the University of Guelph . In the past we have explored the photographic image as an art form in an exhibition on the history of the still photograph from 1845 to 1970 . But this is our first exhibition of a sampling of video tape used as an expressive medium by artists . The selection of tapes was governed by our intention of presenting a show typifying what is happening in video art today . For this reason we have included tapes by established artists, faculty and students . At the University of Guelph courses in video art have been taught by Allyn Lite, Eric Cameron and Noel Harding and have been offered to students in the Department of Fine Art about once a year for the past three years . Arising out of the teaching of video tape an exchange program has been organized with the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and another planned with the California College of Arts and Crafts . Examples of tapes by students from these two schools and from this university are included in the exhibition . We are grateful to Ian Easterbrook for co-ordinating the administrative and technical requirements of this exhibition, also to Noel Harding for contacting artists and to Eric Cameron for writing the introduction to the exhibition . -

Ron Shuebrook

RON SHUEBROOK Home Address: 95 Nottingham Street Guelph, ON N1H 3M9 Home Telephone: Telephone: (519) 766-4744 E-mail Address: [email protected] Canadian Citizen since 1987 I. GENERAL INFORMATION A. Education Dates Attended Degree Certificate Date Granted Institution Kent State University, Ohio 1970-72 MFA with major in painting, and June, 1972 additional studies in printmaking, sculpture, philosophy, and art history Blossom-Kent Summer Program, 1971 (Summer) Graduate coursework in painting Kent State University with visiting artists R. B. Kitaj, Leon Golub, and others Fine Arts Work Center, 1969-70 Fellowship in painting Provincetown, Massachusetts with Myron Stout, Fritz Bultman, Phillip Malicoat, Robert Motherwell, and others Kutztown University, Pennsylvania 1968-69 MEd in Art Education 1969 Haystack Mountain School of 1965 & 1967 Graduate coursework in Crafts, Deer Isle, Maine (Summers) printmaking and painting Kutztown University, Pennsylvania 1961-65 BSc in Art Education 1965 Pennsylvania Art Teaching Certification, K - 12 B. Recent Academic Appointments July 2008 to Present Professor Emeritus, OCAD University, Toronto, Ontario. May- June 2011 Visiting Instructor, Drawing and Painting Workshop, Haystack Mountain, School of Crafts, Deer Isle, Maine January 19- 29, 2010 Visiting Instructor, Drawing Marathon, New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting & Sculpture, New York City, New York Ron Shuebrook Curriculum Vitae Page 2 of 41 July 1, 2005 – June 30, 2008 Professor, Faculty of Art, Ontario College of Art & Design (now OCAD University), Toronto, Ontario Coordinator and Professor, OCAD Florence Program, Italy, January through May 2007. 2000 to June 30, 2005 President and Chief Executive Officer, Ontario College of Art & Design, Toronto, Ontario. Represented OCAD with the Ministry of Training, Colleges, and Universities, Council of Ontario Universities, Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design, Canadian Association of Institutes of Art and Design, and other external organizations. -

Current, February 20, 2017 University of Missouri-St

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Current (2010s) Student Newspapers 2-20-2017 Current, February 20, 2017 University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: http://irl.umsl.edu/current2010s Recommended Citation University of Missouri-St. Louis, "Current, February 20, 2017" (2017). Current (2010s). 254. http://irl.umsl.edu/current2010s/254 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Current (2010s) by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vol. 50 Issue 1524 The Current February 20, 2017 UMSL’S INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWS Three-year Homecoming Theme Built on Tradition Comes to an End with “Where Tradition Happens” Kat Riddler in the J.C. Penney Auditorium on Editor-in-Chief February 14. Students competed in a series of live events to win the ti- “ here Tradition Happens” tle of Big Man on Campus. Collec- Wwas the theme of the Uni- tion buckets for a penny war were versity of Missouri–St. Louis’ 2017 set up for audience members to vote Homecoming celebration. This for their favorite contestant. All pro- ends the three-part tradition theme ceeds went to benefit Girls, Inc. The started in 2015 to try to build cohe- winner this year was Braxton Per- siveness in the move from the fall ry, senior, physical education. Perry to spring in which Homecoming is won Homecoming King last year held. and was sponsored by the sorority Director of Student Life, Jessi- Delta Zeta. -

2012 April 21

SPECIAL ISSUE MUSIC • • FILM • MERCHANDISE • NEW RELEASES • MUSIC • FILM • MERCHANDISE • NEW RELEASES STREET DATE: APRIL 21 ORDERS DUE: MAR 21 SPECIAL ISSUE ada-music.com 2012 RECORD STORE DAY-RELATED CATALOG Artist Title Label Fmt UPC List Order ST. VINCENT KROKODIL 4AD S 652637321173 $5.99 ST. VINCENT ACTOR 4AD CD 652637291926 $14.98 ST. VINCENT ACTOR 4AD A 652637291919 $15.98 BEGGARS ST. VINCENT MARRY ME BANQUET CD 607618025427 $14.98 BEGGARS ST. VINCENT MARRY ME BANQUET A 607618025410 $14.98 ST. VINCENT STRANGE MERCY 4AD CD 652637312324 $14.98 ST. VINCENT STRANGE MERCY 4AD A 652637312317 $17.98 TINARIWEN TASSILI ANTI/EPITAPH A 045778714810 $24.98 TINARIWEN TASSILI ANTI/EPITAPH CD 045778714827 $15.98 WILCO THE WHOLE LOVE DELUXE VINYL BOX ANTI/EPITAPH A 045778717415 $59.98 WILCO THE WHOLE LOVE ANTI/EPITAPH CD 045778715626 $17.98 WILCO THE WHOLE LOVE ANTI/EPITAPH A 045778715619 $27.98 WILCO THE WHOLE LOVE (DELUXE VERSION) ANTI/EPITAPH CD 045778717422 $21.98 GOLDEN SMOG STAY GOLDEN, SMOG: THE BEST OF RHINO RYKO CD 081227991456 $16.98 GOLDEN SMOG WEIRD TALES RHINO RYKO CD 014431044625 $11.98 GOLDEN SMOG DOWN BY THE OLD MAINSTREAM RYKODISC A 014431032516 $18.98 ANIMAL COLLECTIVE TRANSVERSE TEMPORAL GYRUS DOMINO MS 801390032417 $15.98 ANIMAL COLLECTIVE FALL BE KIND EP DOMINO A 801390024610 $11.98 ANIMAL COLLECTIVE FALL BE KIND EP DOMINO CD 801390024627 $9.98 ANIMAL COLLECTIVE MERRIWEATHER POST PAVILION DOMINO A 801390021916 $23.98 ANIMAL COLLECTIVE MERRIWEATHER POST PAVILION DOMINO CD 801390021923 $15.98 ANIMAL COLLECTIVE STRAWBERRY JAM