Curtain: Poirot's Last Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hercule Poirot's First Case

Hercule Poirot’s First Case MURDER MYSTERY Adapted by Jon Jory Based on The Mysterious Affair at Styles by Agatha Christie © Dramatic Publishing Company Hercule Poirot’s First Case Murder mystery. Adapted by Jon Jory. Based on The Mysterious Affair at Styles by Agatha Christie. Cast: 8m., 4w., with doubling. Who poisoned the wealthy Emily Inglethorpe, and how did the murderer penetrate and escape from her locked bedroom? The brilliant Belgian detective Hercule Poirot makes his unforgettable debut in Jon Jory’s dynamic adaptation of Agatha Christie’s first novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles. Poirot, a Belgian refugee of the Great War, is settling in a small village in England near the remote country manor of Emily Inglethorp, a friend who assisted him in starting his new life. Poirot’s friend, Hastings, arrives as a guest at her home. When Emily is killed, Poirot uses his detective skills to solve the mystery of who killed her. Was it her fawning new husband, Alfred; her volatile housekeeper, Dorcas; her companion, Evelyn Howard; or was it Cynthia Murdoch, the pretty nurse who works in a nearby hospital dispensary? Plot twists and red herrings abound in this fast-paced, dynamic and engaging new adaptation. Simple set. Approximate running time: 80 minutes. Code: HG9. Cover design: Molly Germanotta. ISBN: 978-1-61959-075-5 Dramatic Publishing Your Source for Plays and Musicals Since 1885 311 Washington Street Woodstock, IL 60098 www.dramaticpublishing.com 800-448-7469 © Dramatic Publishing Company Hercule Poirot’s First Case Adapted by JON JORY From the novel by AGATHA CHRISTIE Dramatic Publishing Company Woodstock, Illinois ● Australia ● New Zealand ● South Africa © Dramatic Publishing Company *** NOTICE *** The amateur and stock acting rights to this work are controlled exclusively by THE DRAMATIC PUBLISHING COMPANY, INC., without whose permission in writing no performance of it may be given. -

Christie 62 2.Pdf

p q Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case 3 p q 3 ■ B L Contents A N About Agatha Christie The AgathaK Christie Collection E-Book ExtrasP A Chapters: 1G, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17E, 18, 19 Postscript 6 ■ Copyright www.agathachristie.com About the Publisher Chapter 1 I Who is there who has not felt a sudden startled pang at reliving an old experience, or feeling an old emotion? ‘I have done this before . .’ Why do those words always move one so pro- foundly? That was the question I asked myself as I sat in the train watching the flat Essex landscape outside. How long ago was it that I had taken this selfsame journey? Had felt (ridiculously) that the best of life was over for me! Wounded in that war that for me would always be the war – the war that was wiped out now by a second and a more desperate war. It had seemed in 1916 to young Arthur Hastings that he was already old and mature. How little had I realized that, for me, life was only then beginning. I had been journeying, though I did not know it, to meet the man whose influence over me was to shape 5 p q and mould my life. Actually, I had been going to stay with my old friend, John Cavendish, whose mother, recently remarried, had a country house named Styles. A pleasant renewing of old acquaintanceships, that was all I had thought it, not foreseeing that I was shortly to plunge into all the dark embroilments of a mysterious murder. -

Agatha Christie - Third Girl

Agatha Christie - Third Girl CHAPTER ONE HERCULE POIROT was sitting at the breakfast table. At his right hand was a steaming cup of chocolate. He had always had a sweet tooth. To accompany the chocolate was a brioche. It went agreeably with chocolate. He nodded his approval. This was from the fourth shop he had tried. It was a Danish patisserie but infinitely superior to the so-called French one near by. That had been nothing less than a fraud. He was satisfied gastronomically. His stomach was at peace. His mind also was at peace, perhaps somewhat too much so. He had finished his Magnum Opus, an analysis of great writers of detective fiction. He had dared to speak scathingly of Edgar Alien Poe, he had complained of the lack of method or order in the romantic outpourings of Wilkie Collins, had lauded to the skies two American authors who were practically unknown, and had in various other ways given honour where honour was due and sternly withheld it where he considered it was not. He had seen the volume through the press, had looked upon the results and, apart from a really incredible number of printer's errors, pronounced that it was good. He had enjoyed this literary achievement and enjoyed the vast amount of reading he had had to do, had enjoyed snorting with disgust as he flung a book across the floor (though always remembering to rise, pick it up and dispose of it tidily in the waste-paper basket) and had enjoyed appreciatively nodding his head on the rare occasions when such approval was justified. -

Black Coffee Character Breakdown

Black Coffee Character Breakdown All characters (except those noted below) Speak with an educated British accent. Think Downton Abbey, Upstairs Downstairs, Colin Firth, Alan Rickman, Maggie Smith and Emma Thompson for examples. Dr. Carelli-speaks with an Italian accent that does not have to be that authentic. Inspector Japp is decidedly working class. His accent is more rough, less polished. Think the servants of Downton Abbey or the Northerners of Game of Thrones. Think more Michael Caine, Bob Hoskins, Catherine Tate, and Sean Bean for examples. Miss Treadwell (female, late 20’s-60’s) She is the faithful servant, but at the same time knows all “the dirty laundry” of her employers. Sir Claud Amory (male, 50’s plus) He is the irascible Lord of the manor, who has no affection for his relatives and is devoted solely to his scientific discoveries. Caroline Amory (female, 50’s plus) Claud’s dotty younger, maiden sister who never stops talking. She is very conservative, innocent, and prone to not quite getting the full picture of what goes on around her. She has no idea that half of what she says is funny and often inappropriate. Richard Amory (male, early 30’s-mid 40’s) He is the only son of Claud Amory. He’d rather pursue a military career then be under his father’s thumb. He’s not stupid, but he’s not the scientific genius that his father is. Newly married, he is very much in love with his wife Lucia who he married after a brief whirlwind courtship. Lucia Amory (female, mid 20’s-mid 30’s) She is Richard’s half- English and half-Italian wife who was largely raised throughout the European continent. -

Appointment with Death

PART ONE CHAPTER ONE 'Don't you agree that she's got to be killed?' The words seemed to hang in the still night air, before disappearing into the darkness. It was Hercule Poirot's first night in the city of Jerusalem, and he was shutting his hotel-room window - the night air was a danger to his health! - when he overheard these words. He smiled. 'Even on holiday, I am reminded of crime,' he said to himself. 'No doubt someone is talking about a play or a book.' As he walked over to his bed, he thought about the voice he had heard. It was the voice of a man - or a boy - and had sounded nervous and excited. 'I will remember that voice,' said Hercule Poirot to himself, as he lay down to sleep. 'Yes, I will remember.' In the room next door, Raymond Boynton and his sister Carol looked out of their window into the dark-blue night sky. Raymond said again, 'Don't you agree that she's got to be killed? It can't go on like this - it can't. We must do something - and what else can we do?' Carol said in a hopeless voice, 'If only we could just leave somehow! But we can't - we can't.' 'People would say we were crazy,' said Raymond bitterly. 'They would wonder why we can't just walk out -' Carol said slowly, 'Perhaps we are crazy! ' 'Perhaps we are,' agreed Raymond. 'After all, we are calmly planning to kill our own mother! ' 'She isn't our real mother!' said Carol. -

The ABC Murders

PENGUIN ACTIVE READING Teacher Support Programme Answer keys LEVEL 4 The ABC Murders Book key 5.1 Name Place where Job Relatives/people he/she lived close to victim 1.1 Open answers 1.2 Open answers (1 a 2 c 3 c) Alice Ascher Andover Owned a 1. Franz Ascher tobacco and (husband) 2.1 Possible answers: newspaper 2. Mary Drower 1 his marriage > the time before his marriage shop (niece) 2 Captain Hastings > Hercule Poirot Betty Barnard Bexhill-on- Waitress 1.Megan Barnard 3 The dead woman’s husband owns > The dead sea (sister) 2.Donald Fraser woman owned (fiancé) 4 expensive railway guides > cheap railway timetables Sir Carmichael Churston Retired throat 1. Lady Clarke 5must be a man > could be a man or a woman Clarke specialist. Art (wife) 2.2 1 burglars 2 checked 3 empty 4 shone collector. 2. Franklin Clarke (brother) 5 counter 6 body 7 guide 3. Thora Grey 2.3 1 had been written 2 had been threatened (secretary) 3 had spent 4 had been hit 5 had had 6 had been taken 7 had been left 8 had hoped 5.2 1 f 2 d 3 b 4 a 5 e 6 c 2.4 1 Open answers 5.3 1 may 2 must 3 must 4 may 5 may 2 Open answers (a Poirot b A B C c There will 6 may be another murder. d They don’t know how to 5.4 1 a Mr Cust stop the next murder.) b A suitcase and an ABC railway guide 3.1 1 b 2 c 3 d 4 d 5 b 6 c 7 b 8 d c Open answers (To the railway station) 9 d 10 a 11 b 12 c 2 a Mr Cust has dropped his ticket. -

Hercule Poirot Mysteries in Chronological Order

Hercule Poirot/Miss Jane Marple Christie, Agatha Dame Agatha Christie (1890-1976), the “queen” of British mystery writers, published more than ninety stories between 1920 and 1976. Her best-loved stories revolve around two brilliant and quite dissimilar detectives, the Belgian émigré Hercule Poirot and the English spinster Miss Jane Marple. Other stories feature the “flapper” couple Tommy and Tuppence Beresford, the mysterious Harley Quin, the private detective Parker Pyne, or Police Superintendent Battle as investigators. Dame Agatha’s works have been adapted numerous times for the stage, movies, radio, and television. Most of the Christie mysteries are available from the New Bern-Craven County Public library in book form or audio tape. Hercule Poirot The Mysterious Affair at Styles [1920] Murder on the Links [1923] Poirot Investigates [1924] Short story collection containing: The Adventure of "The Western Star", TheTragedy at Marsdon Manor, The Adventure of the Cheap Flat , The Mystery of Hunter's Lodge, The Million Dollar Bond Robbery, The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb, The Jewel Robbery at the Grand Metropolitan, The Kidnapped Prime Minister, The Disappearance of Mr. Davenheim, The Adventure of the Italian Nobleman, The Case of the Missing Will, The Veiled Lady, The Lost Mine, and The Chocolate Box. The Murder of Roger Ackroyd [1926] The Under Dog and Other Stories [1926] Short story collection containing: The Underdog, The Plymouth Express, The Affair at the Victory Ball, The Market Basing Mystery, The Lemesurier Inheritance, The Cornish Mystery, The King of Clubs, The Submarine Plans, and The Adventure of the Clapham Cook. The Big Four [1927] The Mystery of the Blue Train [1928] Peril at End House [1928] Lord Edgware Dies [1933] Murder on the Orient Express [1934] Three Act Tragedy [1935] Death in the Clouds [1935] The A.B.C. -

Hercule Poirot

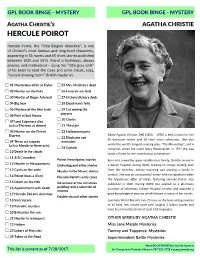

GPL BOOK BINGE - MYSTERY GPL BOOK BINGE - MYSTERY AGATHA CHRISTIE’S AGATHA CHRISTIE HERCULE POIROT Hercule Poirot, the “little Belgian detective”, is one of Christie's most famous and long-lived characters, appearing in 33 novels and 65 short stories published between 1920 and 1975. Poirot is fastidious, always precise, and methodical – using the “little gray cells” of his brain to read the clues and solve classic, cozy, “locked drawing room” British mysteries. 01 Mysterious affair at Styles 25 Mrs. McGinty's dead 02 Murder on the links 26 Funerals are fatal 03 Murder of Roger Ackroyd 27 Hickory dickory dock 04 Big four 28 Dead man's folly 05 Mystery of the blue train 29 Cat among the pigeons 06 Peril at End House 30 Clocks 07 Lord Edgeware dies (a/k/a Thirteen at dinner) 31 Third girl 08 Murder on the Orient 32 Halloween party Express Dame Agatha Christie, DBE (1890 – 1976) is best known for her 33 Elephants can 66 detective novels and 14 short story collections. She also 09 Three act tragedy remember (a/k/a Murder in three acts) wrote the world's longest-running play, “The Mousetrap”, and 6 34 Curtain romances under the name Mary Westmacott. In 1971 she was 10 Death in the clouds made a Dame for her contribution to literature. 11 A B C murders Poirot investigates: stories Born into a wealthy upper-middle-class family, Christie served in 12 Murder in Mesopotamia Underdog and other stories a Devon hospital during WWI, tending to troops coming back 13 Cards on the table Murder in the Mews: stories from the trenches, before marrying and starting a family in London. -

Black Coffee Audition Flyer

T H E A T R E 4106 Way Out West Drive, Suite N, Houston, Texas 77092 P. O. Box 920518, Houston, Texas 77292 713-682-3525 www.theatresuburbia.org Northwest Houston’s Longest Running ALL-VOLUNTEER Playhouse – Established in 1961 AUDITIONS AUDITIONS AUDITIONS TIME: Sunday, January 12, 2020 at 2:00 p.m. and Monday, January 13, 2020 at 7:30 p.m. PLACE: Theatre Suburbia, 4601 Way Out West Drive, Suite N, Houston, TX 77092 SHOW: BLACK COFFEE By Agatha Christie STORY: Accomplished physicist Sir Claud Amory has constructed a workable formula for one of the most deadly weapons known to man - the atom bomb. Hercule Poirot, with the help of Captain Hastings and Inspector Japp, is called in after the formula is mysteriously stolen and Sir Claud is callously murdered. A superbly crafted whodonit with endless red herrings, subplots of infamous spies and an astonishing prophetic storyline about weapons created through 'bombarding the atom'. One of Christie's most gripping country house murder mysteries. CHARACTERS: 10 men and 3 women Ages mixed 20's to 60's Tredwell - The butler or man servant Lucia Amory - A beautiful woman of mid 20's, half Italian Miss Caroline Amory - Elderly, old school, fussy but kind Richard Amory - Ordinary type of good looking Englishman Barbara Amory - Extremely modern young woman, early 20's Edward Raynor - Unremarkable looking man of late 20's Dr. Carelli - Very dark, small mustache suave, speaks with slight accent, Italian Sir Claud Amory - Clean shaven, ascetic-looking man. In his 60's Hercule Poirot - Master Sleuth Belgian Capt. -

Semi-Private Eyes

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1982 Volume I: Society and the Detective Novel Semi-Private Eyes Curriculum Unit 82.01.05 by Anthony F. Franco Benny sits in the cafeteria, opens his carton of milk, and prepares to devour his government-subsidized fried chicken. Within moments several other boys join him with their lunch trays at the table. A few minutes later there are no less than six other boys and several girls jockeying for position at the now crowded table. Benny is captain of the basketball team, good-looking, well-mannered, and adequately intelligent. His popularity is well-deserved. He is adored by students and well-liked by his teachers. Benny will say very little at the table today. The conversation concerns the school’s basketball game of the previous afternoon. Should he agree with the jabbering analysis, it will be looked upon as formal certification of all that transpires. If he should disagree with the minutest detail concerning the game, the conversation will immediately take a different turn. Benny uses his foils well. Tricia is an extremely attractive co-ed at the same school as Benny. Tricia has attained academic honors throughout the year. Each morning a crowd of students surrounds Tricia’s desk as she brushes her hair and freshens her makeup. Throughout the day Tricia is never unaccompanied to class. Her usual companions are a bevy of other girls who do not approach Tricia’s appearance or intelligence. These same girls usually sit near Tricia in her classes and are attentive to every word she says. -

Poirot Reading List

Suggested Reading order for Christie’s Poirot novels and short story collections The most important point to note is – make sure you read Curtain last. Other points to note are: 1. Lord Edgware Dies should be read before After the Funeral 2. Five Little Pigs should be read before Elephants Can Remember 3. Cat Among the Pigeons should be read before Hallowe’en Party 4. Mrs McGinty’s Dead should be read before Hallowe’en Party and Elephants Can Remember 5. Murder on the Orient Express should be read before Murder in Mesopotamia 6. Three Act Tragedy should be read before Hercule Poirot’s Christmas Otherwise, it’s possible to read the Poirot books in any order – but we suggest the following: The Mysterious Affair at Styles 1920 Murder on the Links 1923 Christmas Adventure (short story) 1923 Poirot Investigates (short stories) 1924 Poirot's Early Cases (short stories) 1974 The Murder of Roger Ackroyd 1926 The Big Four 1927 The Mystery of the Blue Train 1928 Black Coffee (play novelisation by Charles Osborne) 1997 Peril at End House 1932 The Mystery of the Baghdad Chest (short story) 1932 Second Gong (short story) 1932 Lord Edgware Dies 1933 Murder on the Orient Express 1934 Three Act Tragedy 1935 Death in the Clouds 1935 The ABC Murders 1936 Murder in Mesopotamia 1936 Cards on the Table 1936 Yellow Iris (short story) 1937 Murder in the Mews (four novellas) 1937 Dumb Witness 1937 Death on the Nile 1937 Appointment with Death 1938 Hercule Poirot's Christmas 1938 Sad Cypress 1940 One, Two Buckle my Shoe 1940 Evil Under -

The ABC Murders

LEVEL 4 Teacher’s notes Teacher Support Programme The ABC Murders Agatha Christie Chapters 1–2: Captain Arthur Hastings travels to London and goes to see his old friend, the retired Belgian EASYSTARTS detective, Hercule Poirot. Poirot shows Hastings a letter he has received in which he is told to watch out for Andover on the 21st of the month. The letter is signed ‘ABC’. Meanwhile, in another part of the country, a man LEVEL 2 named Alexander Bonaparte Cust takes a railway guide and a list of names from his jacket pocket. He marks the first name on the list. Some days later, Poirot receives a phone call from the police, telling him that an old woman LEVEL 3 called Ascher has been murdered in her shop in Andover. Poirot and Hastings travel to Andover and the police tell them that they suspect her husband, a violent drunk. LEVEL 4 About the author Poirot’s letter, however, casts some doubt on the matter and an ABC railway guide has also been found at the Agatha Christie was born in 1890 in Devon, England. scene of the crime. Poirot and Hastings visit the police She was the youngest child of an American father and doctor and then they go to see Mrs Ascher’s niece, Mary an English mother. Her father died when she was eleven Drower, who is naturally very upset. and the young Agatha became very attached to her mother. She never attended school because her mother Chapters 3–4: Poirot and Hastings search Mrs Ascher’s disapproved of it, and she was educated at home in a flat, where they find a pair of new stockings.