A House of Stone for Dr. Mackenzie: Rebuilding Portland’S Architectural History a Lecture Presented by Edward H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portland and Give Russell

side Ldfe on the Inside s Inside tQp. 32 H[e're Out of t\ere 60 Outside Life on the Outside 82 Outside the Classroom.... 102 Toughlnside and Out 122 The Lo Inside and Out Volume 62 1996 University of Portland 5000 N.Willamette Blvd. Portland, Oregon 97203 •Sardine imitation. Michelle Whalen, KtUy Kautsky, John Whalen and Gabe Baker enjoy a cozy afternoon on the swing. c i Don;/ walA in front of me. SJmau not follow. Don Vcoal Aoenindme. SJmau not lead. just walA oesioe me and oe mufrieno. ; y jQloert Cjamus • Mi CQSQ es su casa. Amy Eisenhardt DeeDee Bra hit and Angela Emerv bond on the part) porch. & A Where's Wally? The infamous Pilot mascot takes a break from his strenuous job. AStarting a family. Amy Simpson, Jim Baunach and Rita Trang Nguyen take advantage of the snow. Earning a pilot's liscense. Water sports are no laughing matter to Ryan Darmody and Anna-Lisa Sandstrum. • Tumble dry. Julie Shocnborn leads a rough- and-tumble life in her local dryer. uS/Ps not cunat UOU t/iinA^ ifs wnai tjou tninA aoout. ' -unlnonumous ^ Iclln figgJers, Tun Conneil) nikcs a bite out ol his friend as the) wrestle in a bit oi jello. e> A Safety hug. Sarah Ostler and Carrie MacO'ibbun wear all of their padding for a squeeze. A Heave Ho! Chris Woo hoists up his legendary loft. A Como estas? Ben Hofmeister celebrates Mardi Gras in style. I sn't it amazing how a person can live in one place for years and TJL )Zeve r realize what really goes on in that environment? The amazing K^J7ecret is to look past the end of your nose and observe all the people "JLnsideL , the events that take place, what goes on around the BJL#x>rm s and what crazy things we do to survive this thing called colleg side JLJife on the JLnside O Inside COP. -

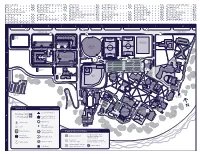

Parking Restricted Areas Symbol Key Alumni Center A-1 AROTC D-3

Alumni Center A-1 Chapel of Christ the Teacher F-4 Etzel Field C-2 Kenna Hall AFROTC G-1 Pilot House F-2 St. Mary’s Student Center F-4 AROTC D-3 Chiles Center D-1 Fields Hall B-2 Lund Family Hall C-1 Physical Plant D-4 Swindells Hall G-3 Bauccio Commons F-4 Clark Library E-2 Franz Hall E-3 Louisiana-Pacifc Romanaggi Hall F-3 Tyson Hall B-1 Beauchamp Recreation Clive Charles Soccer Haggerty Hall C-1 Tennis Center E-4 Saturday Academy B-2 University Bookstore F-2 & Wellness Center C-2 Complex E-1 Health & Counseling Center D-3 Mago Hunt Center D-2 Schoenfeldt Hall B-2 University Events B-2 Bell Tower F-3 Corrado Hall C-3 Holy Cross Court C-2 Mehling Hall D-3 Shiley Hall E-3 Villa Maria Hall C-4 Buckley Center F-3 Dundon-Berchtold Hall F-2 KDUP F-4 Orrico Hall D-3 Shipstad Hall F-1 Waldschmidt Hall G-3 Buckley Center Auditorium F-3 A B C D E F G N Willamette Blvd N Willamette Blvd Alumni Lund Family Hall 5826 Center 1 Varsity Sports Pru Pitch Practice Field Haggerty Hall Merlo Field N Monteith Ave Tyson Hall N McKenna Ave N Van HoutenN Van Ave N Portsmouth Ave Earle A. & Shipstad Hall Sand Virginia H. Chiles Court Center AFROTC N Warren St N Warren St Kenna Hall Schoenfeldt Hall Sand Court Court Beauchamp Recreation Clive Charles Soccer Complex Basketball & Wellness Center Praying Hands Fields Hall Memorial Christie Pilot House Hall 2 N Strong St University Bookstore University Dundon-Berchtold Hall Construction Zone 5618 Events Saturday Holy Cross Loading N Court Zone V Academy an Joe Etzel Only Ho uton Field Mago Hunt Pl N Portsmouth Ave Clark Library Center 5433 ADMISSIONS Buckley Waldschmidt Hall N McCosh St Center Auditorium Franz Hall Buckley Center Romanaggi Hall 3 Health & Counseling Franz River Campus Center Parking Lot Mehling Orrico Swindells Lewis & Clark N Blu Corrado Hall Hall Hall Hall Memorial ff Bell St AROTC Tower Shiley Hall Chapel of Christ St. -

Oregon's Catholic University

U NIVERSITY OF P ORTLAND Oregon’s Catholic University BULLETIN 2007-2008 University Calendar 2007-08 2008-09 Fall Semester Aug. 27 Mon. Aug. 25 Semester begins: Classes begin at 8:10 a.m. Aug. 27 Mon. Aug. 25 Late registration begins Aug. 31 Fri. Aug. 29 Last day to drop courses with full tuition refund Aug. 31 Fri. Aug. 29 Last day to register or change registration (drop/add) Sept. 3 Mon. Sept. 1 Labor Day (Classes in session, offices closed) Oct. 15-19 Mon.-Fri. Oct. 13-17 Fall vacation, no classes Oct. 19 Fri. Oct. 17 Mid-semester (academic warnings) Nov. 1 Varies Nov. 1 Last day to apply for degree in May Nov. 16 Fri. Nov. 14 Last day to change pass/no pass Nov. 16 Fri. Nov. 14 Last day to withdraw from courses Nov. 5-9 Mon.-Fri. Nov. 3-7 Advanced registration for spring semester, seniors and juniors Nov. 12-16 Mon.-Fri. Nov. 10-14 Advanced registration for spring semester, sophomores and freshmen Nov. 22-23 Thurs.-Fri. Nov. 27-28 Thanksgiving vacation (begins 4 p.m., Wednesday) Dec. 7 Fri. Dec. 5 Last day of classes Dec. 10-13 Mon.-Thurs. Dec. 8-11 Semester examinations Dec. 13 Thurs. Dec. 11 Meal service ends with evening meal Dec. 14 Fri. Dec. 12 Degree candidates’ grades due in registrar’s office, 11 a.m. Dec. 14 Fri. Dec. 12 Christmas vacation begins, residence halls close Dec. 17 Mon. Dec. 15 Grades due in registrar’s office, 1 p.m. 2007-08 2008-09 Spring Semester Jan. -

CAMPUS MAP.Indd

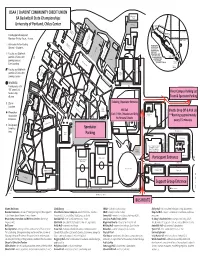

OSAA / OnPOINT COMMUNITY CREDIT UNION Basketball 6A Basketball State Championships Court University of Portland, Chiles Center S Parking Commons Terrace Parking permits required Monday - Friday 8 a.m. - 4 p.m. Parking LD KDUP Bauccio Offices Commons AROTC Admission Visitor Parking Tennis Center KBVM Louisiana-Pacific LD General - Students, Villa Maria Faculty and Staff with Parking St. Mary’s Chapel permits; Visitors with Physical Plant S Parking parking passes; Shiley Hall LD Event parking Bell Tower Faculty and Staff with permits; Visitors with Orrico Hall Mehling Hall Hall Swindells parking passes Corrado Hall RESERVED Parking only with LD S PParkingarking “W” permit 24 River Campus River CampusParking Parking Lot Lot hours a day, Hall Franz Hall Opening October 2014 all year Romanaggi Team & Spectator Parking Buckley Center N. McCosh St. Zipcar B.C. Ticketing / Spectator Entrance Hall Auditorium Location Clark Library Etzel Field Waldschmidt Mago Hunt Will Call Wheelchair Center Shuttle Drop Off & Pick Up LD Cash / VISA / MasterCard Only Holy Cross Accessible Courts **Running approximately EV S LD Entrances No Personal Checks every 15 minutes Designated Howard Hall N. Portsmouth Ave. Smoking Spectator Main Parking N. Strong St. Area Pilot Christie Hall House Parking Fields Hall LD Z Beauchamp Recreation & Wellness Center Chiles Under Construction Parking Opening August 2015 Parking N. Montieth Ave. N. Van Houten Ave. N. Van Schoenfeldt Hall Merlo Field LD S Prusynski Field Participant Entrance (Pru Pitch) Kenna Hall University Events Public Safety N. Warren St. AFROTC Offices Chiles Center S Shipstad Hall Haggerty Hall Tyson Hall LD Parking Alumni Relations Support Group Entrance 7-16-14 Bus Stop #44 Clive Charles Soccer Complex Bus Stop #44 Bus Stop #44 MAP A To I-5 N. -

Facilities Permit Program 10/2/2020 Client and Building List Page 1 of 99

Facilities Permit Program 10/2/2020 Client and Building List Page 1 of 99 111 SW 5th Ave Investors LLC 19-134770-000-00-FC YORDANOS LONG UNICO PROPERTIES Building/Mechanical Inspector: Jeffrey Rago 4364025 Work: (503) 275-7461 Electrical Inspector: David Scranton [email protected] Plumbing Inspector: Chuck Luttmann M Fire Marshal: Mark Cole Building Address Folder Master US Bancorp Plaza:Unico Prop 555 SW OAK ST 19-134803-FC 19-134804-FA US Bancorp Prkng Struct:Unico Prop 129 SW 4TH AVE 20-101725-FC 20-101726-FA US Bancorp Tower:Unico Prop 111 SW 5TH AVE 19-134793-FC 19-134794-FA 200 Market Assoc. 99-125363-000-00-FC LAURA HUNDTOFT CUSHMAN & WAKEFIELD Building/Mechanical Inspector: Jeffrey Rago 2001906 Work: (503) 228-8666 Electrical Inspector: David Scranton Home: (503) 227-2549 Plumbing Inspector: Chuck Luttmann [email protected] Fire Marshal: Mark Cole Building Address Folder Master 200 MarketBldg:200 Market 200 SW MARKET ST 99-125649-FC 04-055199-FA Dielschneider:200 MARKET 71 SW OAK ST 09-124819-FC 09-124820-FA Fechheimer:200 MARKET 233 SW NAITO PKY 09-124830-FC 09-124831-FA FreimannKitchen:200 MARKET 79 SW OAK ST 09-124810-FC 09-124811-FA FreimannRestaurant:200 MARKET 240 SW 1ST AVE 09-124805-FC 09-124806-FA Hallock & McMillan:200 MARKET 237 SW NAITO PKWY 10-198884-FC 10-198885-FA Generated 10/02/2020 11:46 AM by CREPORTS_SVC from DSPPROD City of Portland, BDS - Report Code: 1109007 Facilities Permit Program 10/2/2020 Client and Building List Page 2 of 99 2020 Portland LLC c/o SKB 19-107059-000-00-FC Christina -

Stellar Soccer Player Decides to Redshirt

David Finch University of Portland 5000 N. Willamette Blvd. Portland, Oregon 97203 The Log 1994 Vol.60 ttt Taking A Moment to Rest (Left) After a grueling cross country meet, Amy Blackwell pauses briefly. Ski Ball Kids (Both above) Shuffling through the crowd of college students at Mt. Hood, these UP students enjoy themselvesat the party. C-/ Introduction *. L -, All Tangled Up (Left) Getting into the Orientation activities at Playfair, new students like Trista Grantz get their first taste of UP. Under A Spell (Above) Lined up on stage at BC Aud, these students find themselves somewhat spell-bound, under the influence of a hypnotist. Stop It Right There, Mister! Gaining valuable self-defense techniques in Mehlings lounge, sophomore Michelle Sam learns the proper way to stop an attacker. Intro duct ction fZ* Thuy Nguyen Watch Out! (Left) Keeping the ball out of reach of his defender, junior guard Ray Ross shows why the UP men's basketball team had such an outstanding year. The Pumpkin Patch (Above) Holding on to their prized pumpkins, friends Ashley Amato, Kristie Mausen, Dana Underwood, and Chizuru Sugai get ready for Halloween. Cultivated Tastes At the International Club's Mexican dinner, students line up to dish up some foreign cuisine. £->y _Z^w\r 9 notion F^^^^^^l i i / David Finch Stylin' (Left) All decked out in their coats and ties, Denny Moeun, Chris "Thumper" Monfor, and Brad Hellenthal await their dates for Homecoming. Ladies of the Night (Above) Halloween brings out the best in friends Rachel Stahl, Leah Provost, and Ashley Amato. -

Bulletin 2009-2010

Bulletin 2009–2010 University Calendar 2009-10 2010-11 Fall Semester Aug. 31 Mon. Aug. 30 Semester begins: Classes begin at 8:10 a.m. Aug. 31 Mon. Aug. 30 Late registration begins Sept. 4 Fri. Sept. 3 Last day to drop courses with full tuition refund Sept. 4 Fri. Sept. 3 Last day to register or change registration (drop/add) Sept. 7 Mon. Sept. 6 Labor Day (Classes in session, offices closed) Oct. 19-23 Mon.-Fri. Oct. 18-22 Fall vacation, no classes Oct. 23 Fri. Oct. 22 Mid-semester (academic warnings) Nov. 2 Varies Nov. 1 Last day to apply for degree in May Nov. 10-13 Tue.-Fri. Nov. 9-12 Advanced registration for spring semester, seniors and juniors Nov. 16-19 Mon.-Thurs. Nov. 15-18 Advanced registration for spring semester, sophomores and freshmen Nov. 20 Fri. Nov. 19 Last day to change pass/no pass Nov. 20 Fri. Nov. 19 Last day to withdraw from courses Nov. 26-27 Thurs.-Fri. Nov. 25-26 Thanksgiving vacation (begins 4 p.m., Wednesday) Dec. 11 Fri. Dec. 10 Last day of classes Dec. 14-17 Mon.-Thurs. Dec. 13-16 Semester examinations Dec. 17 Thurs. Dec. 16 Meal service ends with evening meal Dec. 18 Fri. Dec. 17 Degree candidates’ grades due in registrar’s office, 11 a.m. Dec. 18 Fri. Dec. 17 Christmas vacation begins, residence halls close Dec. 21 Mon. Dec. 20 Grades due in registrar’s office, 1 p.m. 2009-10 2010-11 Spring Semester Jan. 11 Mon. Jan. 17 Semester begins: Classes begin at 8:10 a.m. -

University of Portland

UNIVERSITY OF PORTLAND • 2015-16 UNIVERSITY OF PORTLAND 5000 N WILLAMETTE BLVD PORTLAND. OR 97203 ENROLLMENT 3.741 LETICS ARE among one of the many things xmn unite tne uc community ana maice everyone | ans on the edge of their seats and students can't wait to put on all of their UP garb, paint their faces and make signs to support their Big wins this season include the women's soccer team's win against Gonzaga. the men's basketball team dominating BYU and the ^ jail team's season-long winning streak. The student body is also incredibly proud of the men's and women's track team who m championships and Olympic Trials toward the end of the season. Whether it's a win. toss or tie. fans are always read I 4 \JX - - * « y ^^^^m «** L *w •k } V<d NIKE.COM/S0CCe: /** I i£ Ait t "" NIKE.CO i£*- its? The UP community is constantly expanding and granting students access to new opportunities. Three of the newest additions UP family are the Beauchamp Recreational Center, Lund Family Hall and the improved Pilot House. Beauchamp Center has e a place of release and endurance while the Pilot House has served as an awesome new meeting place. Though Lund Family II under construction, it will open its doors Fall 2016 and welcome incoming Pilots to the UP family. Our traditions may stay th< mmunity continues to grow and change for the better. values and traditi r»heology and philosophy courses..students have access to weekly Masses. Catholic organizations, retreats and theological lectures. -

Campus Radio Station Shiley Hall - Donald P

University of Portland Parking permits required Monday - Friday, 8 a.m. - 4 p.m. Basketball Admission Visitor Parking Court General - Students, Faculty and Staff with permits; PARKING Visitors with parking passes; Event parking Co mm Te on rra s ce ic Faculty and Staff with permits; G if N c r I a e K t -P n Visitors with parking passes R a e s A n C C e P T a c i i s O i f s L f KDUP i n D R O B u n A au o e C cc L T Carpool - With Carpool Permit Only om io G KB m N LD V on I M Villa Maria s K t R n A la P P Loading Dock (LD) l a ic s y S C h t. ha P RESERVED - Parking only with “W” permit Ma pe PARKING ry’ l s S L hile D 24 hours a day, all year y H all l l B a Secure Garage Parking in Haggerty Hall el l H s T ll o w o e e r d and Tyson Hall d l n l a i a Mehling r w H r O o S rr Hall ic C o H all Wheelchair Accessible Entrances Emergency Telephones L i D ll P g a AR g H KIN a G n z a ll n Z a a Zipcar Location m y r o H F le r R k e c t u n B e t C . -

CENTURY Teaching, Faith, Service

Rov I . Heynderickx teNj . J . foi Fh • •• ' I Afl ii 100th Anniversary Edition •v.~.--- * •."..-wmm. CENTURY Teaching, Faith, Service # - 1 % "•'^^M , jl *~i , __—^ WW I w ^W\ May 2002- ^ University ajb'*-- ^•^j"'^ ends Defining Moment Campaign UNIVERSITY OF PORTLAND Defining a Century: Teaching TTHE LOG 100'" ANNIVERSARY EDITION Faith One of the many lightposts scattered Service throughout the campus, shown against the colors of a Portland sunset. Pilot fans exhibt their UP pride during a soccer match at Merlo Field. Soccer is only one of the many opportunities UP tans have to show their school spirit. l ocated at ^000 N Willamette Blvd. the University has been a part of the St. fohn's community tor a hundred years. This sign is located at the main entrance of the l niversity. ^ THE L'xivi-.ksn Y OF FORI LAND WHO: 2,509 undergr ad, 437 grads WHAT: The Log, Volume 68 WHEN: 2001-2002 WHERE: 5000 N. Willamette Blvd., Portland, OR 97203 THE LOG TEACHING (2001-2002) Divider I Study I 100th Anniversary CAS Arts I Edition CAS Science i Engineering 24 Nursing 26 STAFF l Education :8 Jamie Worley Business 30 Editor-in-chief Shipstad 32 Kenna 341 Mishelle Weygandt Christie 36 Mehling Assistant Editor 38 Villa 40 Corrado Stacey Boatright 42 Row Housing Layout Design Editor 44 Off-Campus 46 Study Abroad Krindee Hamon 48 Getaways 50 Computer Editor International Week 52] Alexia Rudolph Copy Editor Eddie Moreno Copy Editor SERVICE Divider 94 PHOTO TEAM ASUP 96 CPB 98 Chun - Chang Ch iu CPB Events 100 Coordinator Media 102 Clubs 104- Amanda Straub 110 Photographer ROTC 112 Band/Orchestra 114 Ginger Em rick Volunteer Services 116- 118 Photographer Orrico Hall 120 Men's Soccer 122 Amanda Van Dyke Women's Soccer 124 Photographer Cross Country 126 Volleyball 128 ADVISER Men's Basketball 130 Michelle Kapitanovich Worn. -

Bulletin 2008–2009 University Calendar

Bulletin 2008–2009 University Calendar 2008-09 2009-10 Fall Semester Aug. 25 Mon. Aug. 31 Semester begins: Classes begin at 8:10 a.m. Aug. 25 Mon. Aug. 31 Late registration begins Aug. 29 Fri. Sept. 4 Last day to drop courses with full tuition refund Aug. 29 Fri. Sept. 4 Last day to register or change registration (drop/add) Sept. 1 Mon. Sept. 7 Labor Day (Classes in session, offices closed) Oct. 13-17 Mon.-Fri. Oct. 19-23 Fall vacation, no classes Oct. 17 Fri. Oct. 23 Mid-semester (academic warnings) Nov. 1 Varies Nov. 1 Last day to apply for degree in May Nov. 14 Fri. Nov. 20 Last day to change pass/no pass Nov. 14 Fri. Nov. 20 Last day to withdraw from courses Nov. 4-7 Tue.-Fri. Nov. 10-13 Advanced registration for spring semester, seniors and juniors Nov. 10-13 Mon.-Thurs. Nov. 16-19 Advanced registration for spring semester, sophomores and freshmen Nov. 27-28 Thurs.-Fri. Nov. 26-27 Thanksgiving vacation (begins 4 p.m., Wednesday) Dec. 5 Fri. Dec. 11 Last day of classes Dec. 8-11 Mon.-Thurs. Dec. 14-17 Semester examinations Dec. 11 Thurs. Dec. 17 Meal service ends with evening meal Dec. 12 Fri. Dec. 18 Degree candidates’ grades due in registrar’s office, 11 a.m. Dec. 12 Fri. Dec. 18 Christmas vacation begins, residence halls close Dec. 15 Mon. Dec. 21 Grades due in registrar’s office, 1 p.m. 2008-09 2009-10 Spring Semester Jan. 12 Mon. Jan. 11 Semester begins: Classes begin at 8:10 a.m.