MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: INDIA Mapping Digital Media: India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S.No. Channel Name S/L Service Name S/L Channel Name S/L Channel Name 1 CTVN 1 CTVN 1 SITI Bhakti Bangla 1 SITI Bhakti Bangla 2

ICNCL - FTA Pack - West Bengal - Site 1 ICNCL - FTA Pack - West Bengal - Site 2 ICNCL - FTA Top-up - West Bengal - Site 1 ICNCL - FTA Top-up - West Bengal - Site 2 S.No. Channel Name S/L Service Name S/L Channel Name S/L Channel Name 1 CTVN 1 CTVN 1 SITI Bhakti Bangla 1 SITI Bhakti Bangla 2 Naaptol Bangla[V] 2 Naaptol Bangla[V] 2 SITI Music 2 SITI Music 3 DD Bangla 3 DD Bangla 3 SITI Events 3 SITI Events 4 Sangeet Bangla 4 Sangeet Bangla 4 SITI Events 2 4 SITI Events 2 5 Music F 5 Music F 5 Channel Vision 5 Channel Vision 6 Orange TV 6 Orange TV 6 Sristi TV 6 Sristi TV 7 Kolkata Live 7 Kolkata Live 7 Sonar Bangla 7 Sonar Bangla 8 Khushboo Bangla 8 Khushboo Bangla 8 Sristi Plus 8 Sristi Plus 9 R Plus 9 R Plus 9 Globe TV 9 Globe TV 10 Calcutta News 10 Calcutta News 10 Tara TV 10 Tara TV 11 Kolkata TV 11 Kolkata TV 11 Music Bangla 11 Music Bangla 12 Home Shop 18 12 Home Shop 18 12 SITI Cinema 12 SITI Cinema 13 DD India 13 DD India 13 SITI Tollywood 13 SITI Tollywood 14 DD National 14 DD National 14 S NEWS 14 S NEWS 15 DD Bharati 15 DD Bharati 15 High News 15 High News 16 DD Kisan 16 DD Kisan 16 Artage News 16 Artage News 17 WOW Cinema 17 WOW Cinema 17 Uttorer Khobor 17 Uttorer Khobor 18 NT1 18 NT1 18 Jayatu Bangla 18 Jayatu Bangla 19 Cinema TV 19 Cinema TV 19 Channel 10 19 SDTV Prime 20 ABP News 20 ABP News 20 SDTV Prime 20 Metro 21 India TV 21 India TV 21 Metro 21 SDTV Plus 22 JK 24x7 News 22 LS TV 22 SDTV Plus 22 Home TV 23 LS TV 23 RS TV 23 Home TV 23 Express News 24 RS TV 24 DD News 24 Express News 24 Vision 24 25 DD News 25 Republic -

GC Influencers Have Been Chosen Following Research Among Private Practice Lawyers and Other In-House Counsel

v GC Influencers INDIA 2019 Thursday, 14th February 2019 Hyatt Regency Delhi Programme Engaging content, networking and celebration with leading General Counsel and top ranked lawyers globally. GC Influencers For more informationINDIA visit 2019 chambers.com A5-Advert-Forums.idml 1 22/10/2018 12:17 Welcome SARAH KOGAN Editor Chambers Asia-Pacific Meet the most influential General Counsel in India today. Chambers has provided insight into the legal profession for over 30 years. During this time, in-house lawyers and third-party experts have shared their views on the value and importance placed on the role of the General Counsel. No longer just the ethical and legal heart of a business, these professionals now sit as influential participants at board level. Effective mangers, industry pioneers, diversity and CSR champions: these Influencers show the way. Research Methodology: Our GC Influencers have been chosen following research among private practice lawyers and other in-house counsel. We identified the key areas in which GCs have displayed substantial influence: Engaging content, • Effective management and development of an in-house team • Navigation of substantial business projects such as M&A or strategic networking and business change. • Development of litigation strategy and understanding the pressures faced celebration with leading within industry General Counsel and top • Bringing diversity & inclusion and CSR to the forefront of industry. ranked lawyers globally. • Ability to influence and respond to regulatory change Our aim is to celebrate excellence within the legal profession. This dynamic hall of fame encourages collaboration among the in-house legal community. Our GC Influencers have created best practice pathways endorsed by both private practice and other in-house lawyers. -

Indian Entertainment and Media Outlook 2010 2 Indian Entertainment and Media Outlook 2010 Message

Indian entertainment and media outlook 2010 2 Indian entertainment and media outlook 2010 Message To our clients and friends both in and beyond the entertainment and media industry : Welcome to the 2010 edition of PricewaterhouseCoopers’ Indian Entertainment and Media (E&M) Outlook, covering the forecast period of 2010–2014. Our forecasts and analysis for this edition focus on eight major E&M industry segments and one emerging segment. Each segment details out the key trends observed and challenges faced apart from providing the prospects for the segment. In the industry overview section, we have highlighted the key theme observed during 2009 and what we perceive as future trends in the coming years. We have a chapter on the tax and regulatory impact on the various E&M segments and for the very first time we have included a chapter on how technology can be leveraged in the E&M industry. In 2009, the economy severely impacted the world, translating into steep declines in advertisement as well as consumer spending. India though impacted, did manage to show growth with increased consumer spending as well as innovative action on the part of the industry. Against this backdrop, across the world, except certain markets, speed of digital spending increased due to changing consumer behavior as well as technology available to deliver the same. In India, while the spend on digital media is likely to grow, it is unlikely that it will dominate in the forecast period. This is largely due to the relative unavailability as well as unaffordability of the broadband and mobile infrastructure. -

Radio (FM) Advertising and Consumer Behavior

Radio (FM) Advertising and Consumer Behavior Dr. Mahesh Mukund Deshpande Radio (FM) Advertising and Consumer Behavior India | UAE | Nigeria | Uzbekistan | Montenegro Radio (FM) Advertising and Consumer Behavior Dr. Mahesh Mukund Deshpande Copyright 2019 by Dr. Mahesh Mukund Deshpande First Impression: 2019 Radio (FM) Advertising and Consumer Behavior ISBN : 978-81-943209-7-5 Rs. 650/- No part of the book may be printed, copied, stored, retrieved, duplicated and reproduced in any form without the written permission of the author/publisher. DISCLAIMER Information contained in this book has been published by Empyreal Publishing House and has been obtained by the author from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of his knowledge. The author is solely responsible for the contents of the articles compiled in this book. Responsibility of authenticity of the work or the concepts / views presented by the author through this book shall lie with the author. The publisher do not take any responsibility for the same in any manner. Errors, if any, are purely unintentional and readers are requested to communicate such error to the author to avoid discrepancies in future. Published by: Empyreal Publishing House Acknowledgements First and foremost, I am very grateful to my Guide Prof. Dr. M. M. Wankhede offered me an opportunity to study the topic of my thesis and also guided me untiringly from time to time. I heartily thanks for his guidance, support, encouragement and patience. My Sincere thanks to Shri. N. C. Joshi, the Founder-Director of Institute of Science, Poona and Dr. Babanrao Taiwade extended help me by making various literatures, books and research magazines available time to time. -

Bollywood Talkies

INDIA Bollywood Talkies ©Vanessa Vettorello Rahul Bose, actor, at the premiere of “Margarita with a straw” at the Inox multiplex in Nariman Point (Mumbay) The historic single screen cinemas are recently experiencing a deep identity and economic crisis, leading them to a fast disappearance. Simultaneously, multiple modern screen centers are at the peak of their development and success. As well as the entire Indian film industry. The videos parlour instead - big rooms without any comfort and equipped only with a projector - were born in provincial areas where the old cinemas were closing down, trying to keep alive the traditional movie theaters market in a cheaper way. But today, due to growing piracy, the spread of new technologies (smartphones, tablets, laptops) - and last but not least because of their intrinsic illegality (very few video rooms are fully licensed) – they are experiencing themselves also a major crisis. Thus in a few years the world of cinemas in the country could change radically. Even in India then, in rural areas as in large cities, small theaters are being replaced constantly by more advanced but anonymous video centers. Today these three types of theaters - video parlour, single screen halls and modern multiplex - are still attended by different kind of people in a very exclusive way: each one in fact has its own typical goer that identifies it under a social and economic category. Today they represent a perfect picture of India social complexity to be studied and considered under a light-blue Bollywood twilight. Waiters of the Inox multiplex located inside the Amanora Town Centre mall (Hadapsar - Pune) Matinee show at the New Roshan (Grant Road - Mumbai) Maratha Mandir cinema entrance. -

Live ET Now Business Financial News Channel Streaming Online

Watch ET Now Live: Live ET Now Business Financial News Channel St... http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/et-now Platinum Sponsors Gold Sponsors Property: West South North Indiatimes | The Times of India |The Economic Times | More | Log In | Join | Like 991k Follow ET NOW Search for News, Stock Quotes & NAV's Home News Markets IPO Personal Finance Mutual Funds Tech Jobs Opinion Features Blogs Slideshows ET NOW ET Speed ET Now Live Stocks Experts Corporate Markets Auto Tech Policy Finance Commodities Daily Brand Equity Entertainment Results Forex Market Watch SENSEX NIFTY USD/INR Gold (MCX) (Rs/10g.) ET Market News 10 Aug | 04:18PM 18789.34 124.46 5565.65 46.55 60.64 -0.32 27893.00 -7.00 Like 21k You are here: ET Home ›ET NOW Complaint Redressal Markets Live Company Trend Today Price % Change Top Gainers more » Ranbaxy Laboratories 359.40 27.49 Bharat Forge 231.20 16.62 Hindustan Copper 64.00 12.87 Amara Raja Batteries 240.65 10.64 Top Losers more » Cadila Healthcare 707.80 -5.13 Federal Bank 317.70 -4.98 Gitanjali Gems 59.45 -4.96 Yes Bank 282.65 -3.45 Get a Quote UP Next 4:30 PM Buy Now Sell Now Weekend Type Company Name News Videos Views & Recommendations LATEST NEWS TOP NEWS LATEST VIDEOS MOST VIEWED "If we go up 20 or 30 or 40 points, selling will come Who shook Apple’s cart? Stock 'Chennai Express' to enter Rs 200 in at those levels. It will not be easy for the crore club at box office? Nif.. -

ENTERTAINMENT November 2010 ENTERTAINMENT November 2010

ENTERTAINMENT November 2010 ENTERTAINMENT November 2010 Contents Advantage India Market overview Industry Infrastructure Investments Policy and regulatory framework Opportunities Industry associations 2 ADVANTAGE INDIA Entertainment November 2010 Advantage India - capital Increasing investments by the private sector and foreign media and entertainment (M&E) majors have enhanced India‘s entertainment infrastructure such as new multiplexes and digitization of TV distribution and theatre infrastructure. • Digitisation and technological advancements Improving across the value chain are improving the quality • Producing more than 1,000 films entertainment of content and reach, and also leading to new annually, India is the largest infrastructure business models. For example rural DTH producer of films in the world. penetration is three times higher than in urban Digital High • There are more than 500 TV areas, with digital TV penetration rate of 34% in revolution production channels in the country, requiring rural areas as compared to 12% in urban areas volumes 30 hours of fresh programming per week. • A liberalised foreign investment regime Advantage and other regulatory initiatives are resulting in a conducive business India environment for Indian M&E. Large and under • FDI upto 100 per cent is allowed in film Liberal penetrated • In 2008, there were as many as 3.3 billion and advertising, TV broadcasting (except government consumer theatre admissions in India. news) and 26 per cent in newspaper policies base • With the TV segment reaching as many as publishing. Favourable 134 million households in the country, • Migration from fixed to revenue sharing demographics India is one of the largest TV markets in license fee regime in radio segment and the world. -

Genre Channel Name Channel No Hindi Entertainment Star Bharat 114 Hindi Entertainment Investigation Discovery HD 136 Hindi Enter

Genre Channel Name Channel No Hindi Entertainment Star Bharat 114 Hindi Entertainment Investigation Discovery HD 136 Hindi Entertainment Big Magic 124 Hindi Entertainment Colors Rishtey 129 Hindi Entertainment STAR UTSAV 131 Hindi Entertainment Sony Pal 132 Hindi Entertainment Epic 138 Hindi Entertainment Zee Anmol 140 Hindi Entertainment DD National 148 Hindi Entertainment DD INDIA 150 Hindi Entertainment DD BHARATI 151 Infotainment DD KISAN 152 Hindi Movies Star Gold HD 206 Hindi Movies Zee Action 216 Hindi Movies Colors Cineplex 219 Hindi Movies Sony Wah 224 Hindi Movies STAR UTSAV MOVIES 225 Hindi Zee Anmol Cinema 228 Sports Star Sports 1 Hindi HD 282 Sports DD SPORTS 298 Hindi News ZEE NEWS 311 Hindi News AAJ TAK HD 314 Hindi News AAJ TAK 313 Hindi News NDTV India 317 Hindi News News18 India 318 Hindi News Zee Hindustan 319 Hindi News Tez 326 Hindi News ZEE BUSINESS 331 Hindi News News18 Rajasthan 335 Hindi News Zee Rajasthan News 336 Hindi News News18 UP UK 337 Hindi News News18 MP Chhattisgarh 341 Hindi News Zee MPCG 343 Hindi News Zee UP UK 351 Hindi News DD UP 400 Hindi News DD NEWS 401 Hindi News DD LOK SABHA 402 Hindi News DD RAJYA SABHA 403 Hindi News DD RAJASTHAN 404 Hindi News DD MP 405 Infotainment Gyan Darshan 442 Kids CARTOON NETWORK 449 Kids Pogo 451 Music MTV Beats 482 Music ETC 487 Music SONY MIX 491 Music Zing 501 Marathi DD SAHYADRI 548 Punjabi ZEE PUNJABI 562 Hindi News News18 Punjab Haryana Himachal 566 Punjabi DD PUNJABI 572 Gujrati DD Girnar 589 Oriya DD ORIYA 617 Urdu Zee Salaam 622 Urdu News18 Urdu 625 Urdu -

Your Partners in Growth … We Make the Winning Difference

Your Partners in Growth … We Make The Winning Difference MUMBAI | NEW DELHI | BENGALURU | AUSTRALIA | SINGAPORE 3 Decades Of Delivering Success… Full-service Investment bank with strong capabilities in M&A, PE & Corporate Finance Who We Are ➢ Over 100 completed assignments in ~8 years, transacting in 20 countries across 18 Amongst top 5 Investment Banks uniquesectors/Sub Sectors, aggregated value of transactions handled ~USD 5 Bn ➢ Deep business understanding with multi-sector focus, solution driven mind-set and >100 transactions in result-oriented approach last 8 years ➢ Strong relationships with top Indian Business houses & Global IndustryLeaders ➢ Experienced leadership with diverse background supported by well-research Transactions valued ~USD 5 Bn oriented execution team. ➢ ~350 years of collective experience among 40 professionals, completed over 1,000 assignments since inception ~40 Professionals ➢ Low profile but aggressive team, maintaining highest level of ethics & professional standards ~350 years of collective ➢ Impeccable track record of servicing and maintaining live relationship with over experience 1,500 satisfied clients Closed transactions in ➢ Confidence from existing clients with ~70% repeat business and ~70% strike rate >20 Countries ➢ Providing uncompromised and unbiased advice not encumbered by manyconflicts ➢ Strategic stakeholder & exclusive member of Mergers-Alliance (www.mergers- Strong presence in 18 unique sectors/ alliance.com), a network of 17 independent leading investment banks from across subsectors the -

Massanimaldeathunknow N 2 0 1 1

Copernic Agent Search Results Search: mass animal death unknown 2011 (All the words) Found: 321 result(s) on All.Web Date: 3/27/2011 8:21:53 PM 1. Mass animal deaths in winter 2010-2011 | INFOgraphics | RIA ... Large groups of birds, fish and other animals have been found dead in different parts of the world. In many cases, the cause of death remains unknown. http://en.rian.ru/infographics/20110112/162112641.html 92% 2. Mass animal deaths: Social nonsense or scientific unknown? Jan 24, 2011 ... Are the recent reports of mass animal deaths nothing but spurious drivel? Or is there something unseen occurring? If so, what could it be, ... http://gleaner.rutgers.edu/2011/01/24/mass-animal-deaths-social-nonsense-or-scientific-unknown/ 91% 3. Sudden global death of birds & fishes! - Explore, Experience ... UPDATE: You can see the latest updates on the Mass Animal Death Database page that ... Actual Cause : Unknown Date: Jan 3, 2011 at 5:24 PM CST News. Louisiana QTY: 500 http://simontay78.com/paranormal/sudden-global-death-of-birds-fishes/ 91% 4. Mass Animal Deaths: Who is The Killer? | Scienceray Who is the killer that is responsible for each mass animal death ... However, this time the source is unknown. Let us take ... End of The World on March 31 ,2011; Ten Greatest and ... http://scienceray.com/biology/mass-animal-deaths-who-is-the-killer/ 90% 5. Mass kill of Dolphins, Manatees, Penguins, Bats, Blackbirds ... Quebec bird deaths January 2011 North Carolina US Mass Death among ... Italy, around 3 January 2011 300 doves Cause unknown at this .. -

Modi, Social Media, and Competitive Electoral Populism in India

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 4158–4180 1932–8036/20170005 Fragile Hegemony: Modi, Social Media, and Competitive Electoral Populism in India SUBIR SINHA1 School of Oriental and African Studies, London, UK Direct and unmediated communication between the leader and the people defines and constitutes populism. I examine how social media, and communicative practices typical to it, function as sites and modes for constituting competing models of the leader, the people, and their relationship in contemporary Indian politics. Social media was mobilized for creating a parliamentary majority for Narendra Modi, who dominated this terrain and whose campaign mastered the use of different platforms to access and enroll diverse social groups into a winning coalition behind his claims to a “developmental sovereignty” ratified by “the people.” Following his victory, other parties and political formations have established substantial presence on these platforms. I examine emerging strategies of using social media to criticize and satirize Modi and offering alternative leader-people relations, thus democratizing social media. Practices of critique and its dissemination suggest the outlines of possible “counterpeople” available for enrollment in populism’s future forms. I conclude with remarks about the connection between activated citizens on social media and the fragility of hegemony in the domain of politics more generally. Keywords: Modi, populism, Twitter, WhatsApp, social media On January 24, 2017, India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), proudly tweeted that Narendra Modi, its iconic prime minister of India, had become “the world’s most followed leader on social media” (see Figure 1). Modi’s management of—and dominance over—media and social media was a key factor contributing to his convincing win in the 2014 general election, when he led his party to a parliamentary majority, winning 31% of the votes cast. -

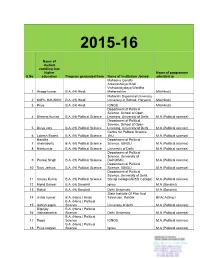

5.2.2 List of Students Progression (Signed).Pdf

2015-16 Name of student enrolling into higher Name of programme S.No education Program graduated from Name of institution Joined admitted to Mahatma Gandhi Antarrashtriya Hindi Vishwavidyalaya,Wardha 1 Anoop kumar B.A. (H) Hindi Maharashtra MA(Hindi) Maharshi Dayanand University 2 KAPIL KAUSHIK B.A. (H) Hindi University in Rohtak, Haryana MA(Hindi) 3 Priya B.A. (H) Hindi IGNOU MA(Hindi) Department of Political Science, School of Open 4 Dheeraj Kumar B.A. (H) Political Science Learning, University of Delhi M.A.(Political science) Department of Political Science, School of Open 5 Divya vats B.A. (H) Political Science Learning, University of Delhi M.A.(Political science) Centre for Political Science, 6 Lokesh Swami B.A. (H) Political Science JNU M.A.(Political science) Nandita Department of Political 7 chakraborty B.A. (H) Political Science Science, IGNOU M.A.(Political science) 8 Nitinkumar B.A. (H) Political Science University of Delhi M.A.(Political science) Department of Political Science, University of 9 Pankaj Singh B.A. (H) Political Science Delhi(KMC) M.A.(Political science) Department of Political 10 Sajni Jethwa B.A. (H) Political Science Science, IGNOU M.A.(Political science) Department of Political Science, University of Delhi, 11 Sanjay Kumar B.A. (H) Political Science Shivaji College(ARSD College) M.A.(Political science) 12 Mohd Sarwar B.A. (H) Sanskrit Ignou M.A.(Sanskrit) 13 Rahul B.A. (H) Sanskrit Delhi University M.A.(Sanskrit) State Institute Of Film And 14 vishal kumar B.A. (Hons.) Hindi Television, Rohtak BFA( Acting ) B.A. (Hons.) Political 15 Ashish sapra Science University of delhi M.A.(Political science) Digvijay B.A.