Heterotrophic Plate Count Bacteria—What Is Their Significance in Drinking Water?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Dose Antimicrobial Protocols for Canine Urinary Tract Infections

High Dose Antimicrobial Protocols for Canine Urinary Tract Infections Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Masters of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sara J. Irom, D.V.M. Graduate Program in Veterinary Clinical Sciences The Ohio State University 2010 Thesis Committee: Joshua Daniels, Advisor Dennis Chew Andrew Hillier Copyright by Sara J. Irom 2010 Abstract Background: Treatment for canine urinary tract infections (UTI) typically consists of 7- 14 days of empirically chosen antimicrobial drugs. Enrofloxacin is a veterinary approved fluoroquinolone (FQ) antimicrobial and is useful for treatment of canine UTI. Ciprofloxacin, the primary metabolite of enrofloxacin, contributes additive antimicrobial activity. Higher doses of FQs may inhibit the emergence of antimicrobial resistance. Objectives: 1) Determine if dogs with naturally occurring uncomplicated UTI have equivalent microbiologic cure with a high dose short duration protocol of enrofloxacin, compared to a standard antimicrobial protocol. 2) Measure urine concentrations of enrofloxacin, and ciprofloxacin, following a 20mg/kg single oral dose in healthy dogs (n=6). Animals: Client-owned dogs with naturally occurring, uncomplicated UTI (n=38), and healthy dogs owned by students and staff of OSU-VMC (n=6). Methods: A multi-center clinical trial was conducted. Dogs were assigned to 1 of 2 groups in a randomized blinded manner. Dogs in group 1 received treatment with 18- 20mg/kg oral enrofloxacin (Baytril®) once daily for 3 consecutive days. Dogs in Group 2 were treated with 13.75-25mg/kg oral amoxicillin-clavulante (Clavamox®) twice daily ii for 14 days. Urine and plasma concentrations of enrofloxacin and ciprofloxacin were measured following a single dose of 20mg/kg oral enrofloxacin in 6 healthy dogs. -

Bacteriological Contamination of Drinking Water Wells

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Bureau of Drinking Water and Groundwater PUB-DG-003-2017 Bacteriological Contamination of Drinking Water Wells ost private wells provide a safe and uncontaminated source of drinking Mwater. Some wells do however become contaminated with bacteria. Fortunately certified labs can easily test water for coliform bacteria, a common indicator of bacterial contamination in wells. To ensure your well is not contaminated, it is a good idea to regularly test your water. You should have your water tested at least annually and whenever you notice a change in the taste, odor or color of the water. Most bacteria entering the ground surface along with rainwater or snowmelt are filtered out as the water seeps through the soil. Several strains of bacteria can survive a long time and find their way into the groundwater by moving through coarse soils, shallow fractured bedrock, quarries, sinkholes, inadequately grouted wells or cracks in the well casing. Insects or small rodents can also carry bacteria into wells with inadequate caps or seals. Coliform bacteria are naturally occurring in soil and are found on vegetation and in surface waters. Water from a well properly located and constructed should be free of coliform bacteria. While coliform bacteria do not cause illness in healthy individuals, their presence in well water indicates the water system is at risk to more serious forms of contamination. The presence of another type of bacteria, Escherichia coli (E. coli), indicates fecal contamination of the water. Fecal coliform bacteria inhabit the intestines of warm-blooded animals and are typically found in their fecal matter. -

Total and Fecal Coliform Bacteria

TOTAL AND FECAL COLIFORM BACTERIA The coliform bacteria group consists of several types of bacteria belonging to the family enterobacteriaceae. These mostly harmless bacteria live in soil, water, and the digestive system of animals. Fecal coliform bacteria, which belong to this group, are present in large numbers in the feces and intestinal tracts of humans and other warm-blooded animals, and can enter water bodies from human and animal waste. If a large number of fecal coliform bacteria (over 200 colonies/100 milliliters or 200 cfu/100 ml) are found in water, it is possible that pathogenic (disease- or illness-causing) organisms are also present in the water. Fecal coliform by themselves are usually not pathogenic; they are indicator organisms, which means they may indicate the presence of other pathogenic bacteria. Pathogens are typically present in such small amounts it is impractical monitor them directly. For more information on E. coli and other pathogenic bacteria, see the U.S. FDA Center for Food Safety & Applied Nutrition's "Bad Bug Book" . Swimming in waters with high levels of fecal coliform bacteria increases the chance of developing illness (fever, nausea or stomach cramps) from pathogens entering the body through the mouth, nose, ears, or cuts in the skin. Diseases and illnesses that can be contracted in water with high fecal coliform counts include typhoid fever, hepatitis, gastroenteritis, dysentery and ear infections. Fecal coliform, like other bacteria, can usually be killed by boiling water or by treating it with chlorine. Washing thoroughly with soap after contact with contaminated water can also help prevent infections. -

Detection and Enumeration of Coliforms in Drinking Water: Current Methods and Emerging Approaches

Journal of Microbiological Methods 49 (2002) 31–54 www.elsevier.com/locate/jmicmeth Detection and enumeration of coliforms in drinking water: current methods and emerging approaches Annie Rompre´ a, Pierre Servais b,*, Julia Baudart a, Marie-Rene´e de-Roubin c, Patrick Laurent a aNSERC Industrial Chair on Drinking Water, Civil, Geological and Mining Engineering, Ecole Polytechnique of Montreal, PO Box 6079, succ. Centre Ville, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H3C 3A7 bEcologie des Syste`mes Aquatiques, Universite´ Libre de Bruxelles, Boulevard du Triomphe, Campus Plaine, CP 221, 1050, Brussels, Belgium cAnjou Recherche, 1 Place de Turenne, 94417 Saint Maurice Cedex, France Accepted 10 September 2001 Abstract The coliform group has been used extensively as an indicator of water quality and has historically led to the public health protection concept. The aim of this review is to examine methods currently in use or which can be proposed for the monitoring of coliforms in drinking water. Actually, the need for more rapid, sensitive and specific tests is essential in the water industry. Routine and widely accepted techniques are discussed, as are methods which have emerged from recent research developments. Approved traditional methods for coliform detection include the multiple-tube fermentation (MTF) technique and the membrane filter (MF) technique using different specific media and incubation conditions. These methods have limitations, however, such as duration of incubation, antagonistic organism interference, lack of specificity and poor detection of slow- growing or viable but non-culturable (VBNC) microorganisms. Nowadays, the simple and inexpensive membrane filter technique is the most widely used method for routine enumeration of coliforms in drinking water. -

The Coliform Kind: E. Coli and Its “Cousins” the Good, the Bad, and the Deadly

Scholars Crossing Faculty Publications and Presentations Department of Biology and Chemistry 10-3-2018 The Coliform Kind: E. coli and Its “Cousins” The Good, the Bad, and the Deadly Alan L. Gillen Liberty University, [email protected] Matthew Augusta Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/bio_chem_fac_pubs Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Gillen, Alan L. and Augusta, Matthew, "The Coliform Kind: E. coli and Its “Cousins” The Good, the Bad, and the Deadly" (2018). Faculty Publications and Presentations. 125. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/bio_chem_fac_pubs/125 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology and Chemistry at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Coliform Kind: E. coli and Its “Cousins” The Good, the Bad, and the Deadly by Dr. Alan L. Gillen and Matthew Augusta on October 3, 2018 Abstract Even though some intestinal bacteria strains are pathogenic and even deadly, most coliforms strains still show evidence of being one of God’s “very good” creations. In fact, bacteria serve an intrinsic role in the colon of the human body. These bacteria aid in the early development of the immune system and stimulate up to 80% of immune cells in adults. In addition, digestive enzymes, Vitamins K and B12, are produced byEscherichia coli and other coliforms. E. coli is the best-known bacteria that is classified as coliforms. The term “coliform” name was historically attributed due to the “Bacillus coli-like” forms. -

Monitoring Antimicrobial Susceptibility in Bacterial Isolates Causing

Nepal Journal of Science and Technology (NJST) (2020), 19(1) : 133-141 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3126/njst.v19i1.29794 Monitoring Antimicrobial Susceptibility in Bacterial Isolates Causing Urinary Tract Infections in a Tertiary NS | Health Original Hospital in Kathmandu Vivek Kumar Singh1*,Mahesh Kumar Chaudhary2, Megha Raj Banjara3, and Reshma Tuladhar3 1Public Health and Infectious Disease Research Center, New Baneshwor, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2 KIST Medical College and Teaching Hospital, Imadole, Lalitpur, Nepal 3Central Department of Microbiology, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Nepal *Corresponding Author [email protected] Abstract Urinary tract infection is the most common infection in females worldwide. One in three women experiences at least one episode of urinary tract infection during their lifetime. The objective of this study was to determine the etiology and antimicrobial profile of urinary tract infection. A cross-sectional study was conducted at a tertiary care hospital in Nepal. Thirteen hundred clean catch mid-stream urine samples were tested through standard microbiological techniques. The isolates from urine samples were identified from biochemical tests. Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed through the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion technique following CLSI guidelines. The prevalence of urinary tract infection was found at 24.23%. Escherichia Coli was a predominant etiological agent followed by Staphylococcus aureus. The majority of the infection was found between the age group 21-40, with females mostly infected. Most of the microorganisms were isolated from emtergency, obstetrics-gynecology, and nephrology wards. Most of the isolates were resistant to ampicillin, whereas the majority of the gram-positive isolates were resistant to penicillin.A large number of isolates were found to be sensitive to Gentamycin and nitrofurantoin. -

Coliform Bacteria in Drinking Water Supplies

WHAT ARE COLIFORMS? TOTAL COLIFORMS, FECAL ARE COLIFORM BACTERIA Coliforms are bacteria that are always COLIFORMS, AND E. COLI HARMFUL? present in the digestive tracts of animals, The most basic test for bacterial Most coliform bacteria do not cause including humans, and are found in their contamination of a water supply is the test disease. However, some rare strains of E. wastes. They are also found in plant and soil for total coliform bacteria. Total coliform coli, particularly the strain 0157:H7, can material. counts give a general indication of the cause serious illness. Recent outbreaks sanitary condition of a water supply. of disease caused by E. coli 0157:H7 have generated much public concern about this “Indicator” A. Total coliforms include bacteria that organism. E. coli 0157:H7 has been found organisms are found in the soil, in water that has been in cattle, chickens, pigs, and sheep. Most of Water pollution caused by fecal influenced by surface water, and in human the reported human cases have been due contamination is a serious problem or animal waste. to eating under cooked hamburger. Cases due to the potential for contracting of E. coli 0157:H7 caused by contaminated B. Fecal coliforms are the group of the diseases from pathogens (disease- drinking water supplies are rare. causing organisms). Frequently, total coliforms that are considered to be concentrations of pathogens from present specifically in the gut and feces fecal contamination are small, and of warm-blooded animals. Because the the number of different possible origins of fecal coliforms are more specific pathogens is large. -

Microbial Populations of Fresh and Cold Stored Donkey Milk by High-Throughput Sequencing Provide Indication for a Correct Management of This High-Value Product

applied sciences Communication Microbial Populations of Fresh and Cold Stored Donkey Milk by High-Throughput Sequencing Provide Indication for A Correct Management of This High-Value Product Pasquale Russo 1,*, Daniela Fiocco 2 , Marzia Albenzio 1, Giuseppe Spano 1 and Vittorio Capozzi 3 1 Department of Sciences of Agriculture, Food, and Environment, University of Foggia, via Napoli 25, 71122 Foggia, Italy; [email protected] (M.A.); [email protected] (G.S.) 2 Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Foggia, Viale Pinto 1, 71122 Foggia, Italy; daniela.fi[email protected] 3 Institute of Sciences of Food Production, National Research Council (CNR), c/o CS-DAT, Via Michele Protano, 71121 Foggia, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 12 March 2020; Accepted: 25 March 2020; Published: 28 March 2020 Abstract: Donkey milk is receiving increasing interest due to its attractive nutrient and functional properties (but also cosmetic), which make it a suitable food for sensitive consumers, such as infants with allergies, the immunocompromised, and elderly people. Our study aims to provide further information on the microbial variability of donkey milk under cold storage conditions. Therefore, we analysed by high-throughput sequencing the bacterial communities in unpasteurized donkey milk just milked, and after three days of conservation at 4 ◦C, respectively. Results showed that fresh donkey milk was characterized by a high incidence of spoilage Gram-negative bacteria mainly belonging to Pseudomonas spp. A composition lower than 5% of lactic acid bacteria was found in fresh milk samples, with Lactococcus spp. being the most abundant. -

Coliform Bacteria Sometimes Found in Drinking Water Wells

Private Drinking Water Wells Fact Sheet Florida Department of Health, Bureau of Environmental Health This fact sheet discusses possible health risks from coliform bacteria sometimes found in drinking water wells. Coliform Bacteria What are coliform bacteria? Bacteria are a type of life form we can only see with a microscope. Also known as microbes, they occur throughout the environment. Coliform bacteria are a large group of related types of them. Most are harmless to humans, but some, such as E. coli, relate to the gut tracts of warm-blooded animals. They can cause disease with symptoms like severe diarrhea. If most coliform bacteria are harmless, why do we test for them? Just because a test finds coliform bacteria in your well water, it does not mean that drinking it is going to make you sick. It does show that there is a way for bacteria to get into your well water. When found, it shows that the types of bacteria that cause disease (or pathogens) can also get into your well. Coliform bacteria serve as stand-ins (or indicator organisms) to see if pathogens may also exist in sampled water. It is not practical to test for all possible bacteria that might cause disease. Coliforms are easy to grow, and it does not cost a lot of money to test for them. The reason to test for them is that if no coliforms show up in the water, the chances of pathogens being there are very low. What should I do if my water contains coliform bacteria? It is easy for just one bacteria to contaminate a water sample by mistake. -

Total Coliform Bacteria, E. Coli & PRIVATE WELLS

Total Coliform Bacteria, E. coli & PRIVATE WELLS What are total coliform bacteria and E. coli? Total coliform bacteria are a group of microorganisms found in soil and surface water. Total coliform bacteria water tests look at all coliform bacteria in water. This includes fecal coliform bacteria, which are a group of bacteria found in the intestines and feces of animals and humans. E. coli or Escherichia coli is a type of fecal coliform bacteria. There are many strains of E. coli. When should I be concerned about coliform bacteria or E. coli? How does coliform bacteria and You should be concerned if coliform bacteria or E. coli are E. coli get in my private well water? present in your well water. Rain may wash coliform bacteria or E. coli from soil on The NC Department of Environmental Quality the surface to groundwater. Coliform bacteria or E. coli developed a groundwater standard of 1 colony of can also enter your water if your private well is poorly coliform bacteria in 100 milliliters of water (colonies/ constructed, cracked or unsealed. mL). Ground water standards are developed to protect public health. This standard was developed in 2013. How can coliform bacteria The US Environmental Protection Agency requires follow up testing and treatment when coliform bacteria or E. coli affect my health? or E. coli is found in any public water supply system across Most coliform bacteria and E. coli strains will not make you the country. Public drinking water guidance are based on sick. The presence of some types of coliform bacteria in the public health protection and cost of treatment/testing at water signal the presence of feces or sewage waste. -

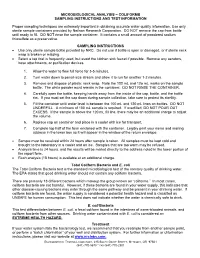

Microbiological Analysis – Coliforms Sampling Instructions and Test Information

MICROBIOLOGICAL ANALYSIS – COLIFORMS SAMPLING INSTRUCTIONS AND TEST INFORMATION Proper sampling techniques are extremely important in obtaining accurate water quality information. Use only sterile sample containers provided by Neilson Research Corporation. DO NOT remove the cap from bottle until ready to fill. DO NOT rinse the sample container. It contains a small amount of powdered sodium thiosulfate as a preservative. SAMPLING INSTRUCTIONS • Use only sterile sample bottle provided by NRC. Do not use if bottle is open or damaged, or if sterile neck wrap is broken or missing. • Select a tap that is frequently used, but avoid the kitchen sink faucet if possible. Remove any aerators, hose attachments, or purification devices. 1. Allow the water to flow full force for 3-5 minutes. 2. Turn water down to pencil-size stream and allow it to run for another 1-2 minutes. 3. Remove and dispose of plastic neck wrap. Note the 100 mL and 12o mL marks on the sample bottle. The white powder must remain in the container. DO NOT RINSE THE CONTAINER. 4. Carefully open the bottle, keeping hands away from the inside of the cap, bottle, and the bottle rim. If you must set the cap down during sample collection, take care to protect its sterility. 5. Fill the container until water level is between the 100 mL and 120 mL lines on bottles. DO NOT UNDERFILL. A minimum of 100 mL sample is required. If overfilled, DO NOT POUR OUT EXCESS. If the sample is above the 120 mL fill line, there may be an additional charge to adjust the volume. -

Reservoirs of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Retail Raw Milk Jinxin Liu1,2, Yuanting Zhu1,2, Michele Jay-Russell3, Danielle G

Liu et al. Microbiome (2020) 8:99 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-020-00861-6 RESEARCH Open Access Reservoirs of antimicrobial resistance genes in retail raw milk Jinxin Liu1,2, Yuanting Zhu1,2, Michele Jay-Russell3, Danielle G. Lemay4,5,6 and David A. Mills1,2,7* Abstract Background: It has been estimated that at least 3% of the USA population consumes unpasteurized (raw) milk from animal sources, and the demand to legalize raw milk sales continues to increase. However, consumption of raw milk can cause foodborne illness and be a source of bacteria containing transferrable antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs). To obtain a comprehensive understanding of the microbiome and antibiotic resistome in both raw and processed milk, we systematically analyzed 2034 retail milk samples including unpasteurized milk and pasteurized milk via vat pasteurization, high-temperature-short-time pasteurization, and ultra-pasteurization from the United States using complementary culture-based, 16S rRNA gene, and metagenomic sequencing techniques. Results: Raw milk samples had the highest prevalence of viable bacteria which were measured as all aerobic bacteria, coliform, and Escherichia coli counts, and their microbiota was distinct from other types of milk. 16S rRNA gene sequencing revealed that Pseudomonadaceae dominated raw milk with limited levels of lactic acid bacteria. Among all milk samples, the microbiota remained stable with constant bacterial populations when stored at 4 °C. In contrast, storage at room temperature dramatically enriched the bacterial populations present in raw milk samples and, in parallel, significantly increased the richness and abundance of ARGs. Metagenomic sequencing indicated raw milk possessed dramatically more ARGs than pasteurized milk, and a conjugation assay documented the active transfer of blaCMY-2, one ceftazidime resistance gene present in raw milk-borne E.