The Missing Future: Moma And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12

Oral history interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12 Funding for this interview was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Ann Wilson on 2009 April 19-2010 July 12. The interview took place at Wilson's home in Valatie, New York, and was conducted by Jonathan Katz for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ANN WILSON: [In progress] "—happened as if it didn't come out of himself and his fixation but merged. It came to itself and is for this moment without him or her, not brought about by him or her but is itself and in this sudden seeing of itself, we make the final choice. What if it has come to be without external to us and what we read it to be then and heighten it toward that reading? If we were to leave it alone at this point of itself, our eyes aging would no longer be able to see it. External and forget the internal ordering that brought it about and without the final decision of what that ordering was about and our emphasis of it, other eyes would miss the chosen point and feel the lack of emphasis. -

G O Ld C O Ast a Rts C Enter

CLASSES & PROGRAMS WINTER/SPRING 2020 Gold Coast Arts Center Arts Coast Gold Artwork Esphyr Slobodkina, 1960. Used by permission. All rights reserved. BOARD OF DIRECTORS FOUNDER, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Regina Gil EXECUTIVE BOARD PRESIDENT Jon Kaiman Contents FEATURED PAST PRESIDENT Michael S. Glickman EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT/TREASURER About the Artist . 2 ABOUT THE COVER ARTIST Ralph S. Heiman, CPA Hours & Closings . 2 VICE PRESIDENT, OPERATIONS Esphyr Slobodkina (1908–2002) was probably best PROGRAMS & EVENTS Dohn Samuel Schildkraut Directions . 2 known as an author and illustrator of children’s books. VICE PRESIDENT, DEVELOPMENT Dance . 4 Her Caps for Sale has been in continuous print for Joseph Gil almost 80 years and has been translated into more than Ceramics . 7 RECORDING SECRETARY a dozen languages. In addition to her own writing, she Michele K. Heiman Art . 8 illustrated a number of books for the well-known writer MEMBERS-AT-LARGE Adults . 9 and publisher, Margaret Wise Brown. However, in her LIVE PERFORMANCES, SHOWS & EXHIBITIONS Steven Blank Artreach . 9 own eyes and those of her contemporaries, her greatest Jerry Siegelman accomplishments were in the field of abstract art. In addition to the School for the Arts, our facilities include Your Big Break Competition 2020 Martin Sokol Music . 10 a black box theater that hosts live performances Submissions open December 2019. The annual search Jeffrey S. Wiesenfeld Born in Chelyabinsk, Russia and raised in Harbin, Early Childhood . 11 and programs all year long, as well as a free public art for Long Island’s next big musical act continues for its COUNSEL Manchuria (China), Esphyr Slobodkina immigrated gallery that features a rotating schedule of curated Katten Muchin Rosenman LLP Acting & Musical Theatre . -

The American Public Art Museum: Formation of Its Prevailing Attitudes

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1982 The American Public Art Museum: Formation of its Prevailing Attitudes Marilyn Mars Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Art Education Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1302 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE AMERICAN PUBLIC ART MUSEUM: FORMATION OF ITS PREVAILING ATTITUDES by MARILYN MARS B.A., University of Florida, 1971 Submitted to the Faculty of the School of the Arts of Virginia Commonwealth University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of d~rts RICHMOND, VIRGINIA December, 1982 INTRODUCTION In less than one hundred years the American public art museum evolved from a well-intentioned concept into one of the twentieth century's most influential institutions. From 1870 to 1970 the institution adapted and eclipsed its European models with its didactic orientation and the drive of its founders. This striking development is due greatly to the ability of the museum to attract influential and decisive leaders who established its attitudes and governing pol.icies. The mark of its success is its ability to influence the way art is perceived and remembered--the museum affects art history. An institution is the people behind it: they determine its goals, develop its structure, chart its direction. -

2017 Abstracts

Abstracts for the Annual SECAC Meeting in Columbus, Ohio October 25th-28th, 2017 Conference Chair, Aaron Petten, Columbus College of Art & Design Emma Abercrombie, SCAD Savannah The Millennial and the Millennial Female: Amalia Ulman and ORLAN This paper focuses on Amalia Ulman’s digital performance Excellences and Perfections and places it within the theoretical framework of ORLAN’s surgical performance series The Reincarnation of Saint Orlan. Ulman’s performance occurred over a twenty-one week period on the artist’s Instagram page. She posted a total of 184 photographs over twenty-one weeks. When viewed in their entirety and in relation to one another, the photographs reveal a narrative that can be separated into three distinct episodes in which Ulman performs three different female Instagram archetypes through the use of selfies and common Instagram image tropes. This paper pushes beyond the casual connection that has been suggested, but not explored, by art historians between the two artists and takes the comparison to task. Issues of postmodern identity are explored as they relate to the Internet culture of the 1990s when ORLAN began her surgery series and within the digital landscape of the Web 2.0 age that Ulman works in, where Instagram is the site of her performance and the selfie is a medium of choice. Abercrombie situates Ulman’s “image-body” performance within the critical framework of feminist performance practice, using the postmodern performance of ORLAN as a point of departure. J. Bradley Adams, Berry College Controlled Nature Focused on gardens, Adams’s work takes a range of forms and operates on different scales. -

Dlkj;Fdslk ;Lkfdj

MoMA PRESENTS SCREENINGS OF VIDEO ART AND INTERVIEWS WITH WOMEN ARTISTS FROM THE ARCHIVE OF THE VIDEO DATA BANK Video Art Works by Laurie Anderson, Miranda July, and Yvonne Rainer and Interviews With Artists Such As Louise Bourgeois and Lee Krasner Are Presented FEEDBACK: THE VIDEO DATA BANK, VIDEO ART, AND ARTIST INTERVIEWS January 25–31, 2007 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, January 9, 2007— The Museum of Modern Art presents Feedback: The Video Data Bank, Video Art, and Artist Interviews, an exhibition of video art and interviews with female visual and moving-image artists drawn from the Chicago-based Video Data Bank (VDB). The exhibition is presented January 25–31, 2007, in The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters, on the occasion of the publication of Feedback, The Video Data Bank Catalog of Video Art and Artist Interviews and the presentation of MoMA’s The Feminist Future symposium (January 26 and 27, 2007). Eleven programs of short and longer-form works are included, including interviews with artists such as Lee Krasner and Louise Bourgeois, as well as with critics, academics, and other commentators. The exhibition is organized by Sally Berger, Assistant Curator, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art, with Blithe Riley, Editor and Project Coordinator, On Art and Artists collection, Video Data Bank. The Video Data Bank was established in 1976 at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago as a collection of student productions and interviews with visiting artists. During the same period in the mid-1970s, VDB codirectors Lyn Blumenthal and Kate Horsfield began conducting their own interviews with women artists who they felt were underrepresented critically in the art world. -

Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera

How To Quote This Material ©Jack Fritscher www.JackFritscher.com Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera — Take 2: Pentimento for Robert Mapplethorpe Manuscript TAKE 2 © JackFritscher.com PENTIMENTO FOR ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE FETISHES, FACES, AND FLOWERS Of EVIL1 “He wanted to see the devil in us all... The man who liberated S&M Leather into international glamor... The man Jesse Helms hates... The man whose epic movie-biography only Ken Russell could re-create...” Photographer Mapplethorpe: The Whitney, the NEA and censorship, Schwarzenegger, Richard Gere, Susan Sarandon, Paloma Picasso, Hockney, Warhol, Patti Smith, Scavullo, sex, drugs, rock ’n’ roll, S&M, flowers, black leather, fists, Allen Ginsberg, and, once-upon-a-time, me... The pre-AIDS past of the 1970s has become a strange country. We lived life differently a dozen years ago. The High Time was in full upswing. Liberation was in the air, and so were we, performing nightly our high-wire sex acts in a circus without nets. If we fell, we fell with splendor in the grass. That carnival, ended now, has no more memory than the remembrance we give it, and we give remembrance here. In 1977, Robert Mapplethorpe arrived unexpectedly in my life. I was editor of the San Francisco—based international leather magazine, Drummer, and Robert was a New York shock-and-fetish photographer on the way up. Drummer wanted good photos. Robert, already infamous for his leather S&M portraits, always seeking new models with outrageous trips, wanted more specific exposure within the leather community. Our mutual, professional want ignited almost instantly into mutual, personal passion. -

C100 Trip to Houston

Presented in partnership with: Trip Participants Doris and Alan Burgess Tad Freese and Brook Hartzell Bruce and Cheryl Kiddoo Wanda Kownacki Ann Marie Mix Evelyn Neely Yvonne and Mike Nevens Alyce and Mike Parsons Your Hosts San Jose Museum of Art: S. Sayre Batton, deputy director for curatorial affairs Susan Krane, Oshman Executive Director Kristin Bertrand, major gifts officer Art Horizons International: Leo Costello, art historian Lisa Hahn, president Hotel St. Regis Houston Hotel 1919 Briar Oaks Lane Houston, Texas, 77027 Phone: 713.840.7600 Houston Weather Forecast (as of 10.31.16) Wednesday, 11/2 Isolated Thunderstorms 85˚ high/72˚ low, 30% chance of rain, 71% humidity Thursday, 11/3 Partly Cloudy 86˚ high/69˚ low, 20% chance of rain, 70% humidity Friday, 11/4 Mostly Sunny 84˚ high/63 ˚ low, 10% chance of rain, 60% humidity Saturday, 11/5 Mostly Sunny 81˚ high/61˚ low, 0% chance of rain, 42% humidity Sunday, 11/6 Partly Cloudy 80˚ high/65˚ low, 10% chance of rain, 52% humidity Day One: Wednesday, November 2, 2016 Dress: Casual Independent arrival into George Bush Intercontinental/Houston Airport. Here in “Bayou City,” as the city is known, Houstonians take their art very seriously. The city boasts a large and exciting collection of public art that includes works by Alexander Calder, Jean Dubuffet, Michael Heizer, Joan Miró, Henry Moore, Louise Nevelson, Barnett Newman, Claes Oldenburg, Albert Paley, and Tony Rosenthal. Airport to hotel transportation: The St. Regis Houston Hotel offers a contracted town car service for airport pickup for $120 that would be billed directly to your hotel room. -

LEE KRASNER Public Information (Selected Chronology)

The Museum of Modern Art 79 LEE KRASNER Public Information (Selected Chronology) 1908 Born October 27, Lenore Krassner in Brooklyn, New York. 1926-29 Studies at Women's Art School of Cooper Union, New York City. 1928 Attends Art Students League. 1929-32 Attends National Academy of Design. 1934-35 Works as an artist on Public Works of Art Project and for the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration. Joins the WPA Federal Art Project as an assistant in the Mural Division. 1937-40 Studies with the artist Hans Hofmann. 1940 Exhibits with American Abstract Artists at the American Fine Arts Galleries, New York. 1942 Participates in "American and French Paintings," curated by John Graham at the McMillen Gallery, New York. As a result of the show, begins acquaintance with Jackson Pollock. 1945 Marries Jackson Pollock on October 25 at Marble Collegiate Church, New York. Exhibits in "Challenge to the Critic" with Pollock, Gorky, Gottlieb, Hofmann, Pousette-Dart, and Rothko, at Gallery 67, New York. 1946-49 Creates "Little Image" all-over paintings at Springs, Easthampton. 1951 First solo exhibition, "Paintings 1951, Lee Krasner," at Betty Parsons Gallery, New York. 1953 Begins collage works. 1955 Solo exhibition of collages at Stable Gallery, New York. 1956 Travels to Europe for the first time. Jackson Pollock dies on August 11. 1959 Completes two mosaic murals for Uris Brothers at 2 Broadway, New York. Begins Umber and Off-White series of paintings. 1965 A retrospective, "Lee Krasner, Paintings, Drawings, and Col lages," is presented at Whitechapel Art Gallery in London (circulated the following year to museums in York, Hull, Nottingham, Newcastle, Manchester, and Cardiff). -

Mother Trouble: the Maternal-Feminine in Phallic and Feminist Theory in Relation to Bratta Ettinger's Elaboration of Matrixial Ethics

This is a repository copy of Mother trouble: the maternal-feminine in phallic and feminist theory in relation to Bratta Ettinger's Elaboration of Matrixial Ethics. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/81179/ Article: Pollock, GFS (2009) Mother trouble: the maternal-feminine in phallic and feminist theory in relation to Bratta Ettinger's Elaboration of Matrixial Ethics. Studies in the Maternal, 1 (1). 1 - 31. ISSN 1759-0434 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Mother Trouble: The Maternal-Feminine in Phallic and Feminist Theory in Relation to Bracha Ettinger’s Elaboration of Matrixial Ethics/Aesthetics Griselda Pollock Preface Most of us are familiar with Sigmund Freud’s infamous signing off, in 1932, after a lifetime of intense intellectual and analytical creativity, on the question of psychoanalytical research into femininity. -

Full Diss Reformatted II

“NEWS THAT STAYS NEWS”: TRANSFORMATIONS OF LITERATURE, GOSSIP, AND COMMUNITY IN MODERNITY Lindsay Rebecca Starck A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Gregory Flaxman Erin Carlston Eric Downing Andrew Perrin Pamela Cooper © 2016 Lindsay Rebecca Starck ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Lindsay Rebecca Starck: “News that stays news”: Transformations of Literature, Gossip, and Community in Modernity (Under the direction of Gregory Flaxman and Erin Carlston) Recent decades have demonstrated a renewed interest in gossip research from scholars in psychology, sociology, and anthropology who argue that gossip—despite its popular reputation as trivial, superficial “women’s talk”—actually serves crucial social and political functions such as establishing codes of conduct and managing reputations. My dissertation draws from and builds upon this contemporary interdisciplinary scholarship by demonstrating how the modernists incorporated and transformed the popular gossip of mass culture into literature, imbuing it with a new power and purpose. The foundational assumption of my dissertation is that as the nature of community changed at the turn of the twentieth century, so too did gossip. Although usually considered to be a socially conservative force that serves to keep social outliers in line, I argue that modernist writers transformed gossip into a potent, revolutionary tool with which modern individuals could advance and promote the progressive ideologies of social, political, and artistic movements. Ultimately, the gossip of key American expatriates (Henry James, Djuna Barnes, Janet Flanner, and Ezra Pound) became a mode of exchanging and redefining creative and critical values for the artists and critics who would follow them. -

A Mechanism of American Museum-Building Philanthropy

A MECHANISM OF AMERICAN MUSEUM-BUILDING PHILANTHROPY, 1925-1970 Brittany L. Miller Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Departments of History and Philanthropic Studies, Indiana University August 2010 Accepted by the Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ____________________________________ Elizabeth Brand Monroe, Ph.D., J.D., Chair ____________________________________ Dwight F. Burlingame, Ph.D. Master’s Thesis Committee ____________________________________ Philip V. Scarpino, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the same way that the philanthropists discussed in my paper depended upon a community of experienced agents to help them create their museums, I would not have been able to produce this work without the assistance of many individuals and institutions. First, I would like to express my thanks to my thesis committee: Dr. Elizabeth Monroe (chair), Dr. Dwight Burlingame, and Dr. Philip Scarpino. After writing and editing for months, I no longer have the necessary words to describe my appreciation for their support and flexibility, which has been vital to the success of this project. To Historic Deerfield, Inc. of Deerfield, Massachusetts, and its Summer Fellowship Program in Early American History and Material Culture, under the direction of Joshua Lane. My Summer Fellowship during 2007 encapsulated many of my early encounters with the institutional histories and sources necessary to produce this thesis. I am grateful to the staff of Historic Deerfield and the thirty other museums included during the fellowship trips for their willingness to discuss their institutional histories and philanthropic challenges. -

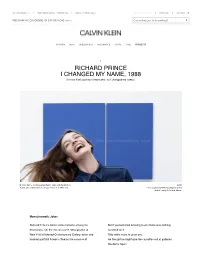

RICHARD PRINCE I CHANGED MY NAME, 1988 (I Never Had a Penny to My Name, So I Changed My Name.)

MY ACCOUNT PREFERRED LOYALTY PROGRAM SIGN UP FOR EMAIL RECENTLY VIEWED WISH LIST MY BAG 0 FREE SHIPPING ON ORDERS OF $99 OR MORE DETAILS* Can we help you find something? WOMEN MEN UNDERWEAR FRAGRANCE HOME SALE PROJECTS 1 RICHARD PRINCE I CHANGED MY NAME, 1988 (I never had a penny to my name, so I changed my name.) Richard Prince, I Changed My Name, 1988 © Richard Prince LULU Acrylic and screen print on canvas (142.5 cm x 198.7 cm) Photographed by Willy Vanderperre at the Rubell Family Collection, Miami. Monochromatic Jokes Richard Prince’s Jokes series remains among his But if you bothered listening to one there was nothing most iconic. On the eve of a 2013 retrospective at recorded on it. New York’s Nahmad Contemporary Gallery, writer and Only white noise to greet you. kindred spirit Bill Powers riffed on the essence of He thought he might give the cassettes out at galleries like demo tapes. these works for the show’s catalog. The piece is Like musicians did at record labels to get signed. excerpted below. Within a year he began silk-screening jokes on canvas. He wasn’t a funny guy. He made them with black text on a white background, He wasn’t the life of the party. but then decided that wasn’t quite right. But most comedy isn’t about entertaining as it is about He painted over them. survival. There’s an installation shot in Spiritual America before And he wanted to live. he destroyed the paintings. He didn’t make art looking for love.