Sadie Benning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OTHER CAMP: RETHINKING CAMP, the 1990S, and the POLITICS of VISIBILITY

OTHER CAMP: RETHINKING CAMP, THE 1990s, AND THE POLITICS OF VISIBILITY By Sarah Margaret Panuska A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of English—Doctor of Philosophy 2019 ABSTRACT Other Camp: Rethinking Camp, the 1990s, and the Politics of Visibility By Sarah Margaret Panuska Other Camp pairs 1990s experimental media produced by lesbian, bi, and queer women with queer theory to rethink the boundaries of one of cinema’s most beloved and despised genres, camp. I argue that camp is a creative and political practice that helps communities of women reckon with representational voids. This project shows how primarily-lesbian communities, whether black or white, working in the 1990s employed appropriation and practices of curation in their camp projects to represent their identities and communities, where camp is the effect of juxtaposition, incongruity, and the friction between an object’s original and appropriated contexts. Central to Other Camp are the curation-centered approaches to camp in the art of LGBTQ women in the 1990s. I argue that curation— producing art through an assembly of different objects, texts, or artifacts and letting the resonances and tensions between them foster camp effects—is a practice that not only has roots within experimental approaches camp but deep roots in camp scholarship. Relationality is vital to the work that curation does as an artistic practice. I link the relationality in the practice of camp curation to the relation-based approaches of queer theory, Black Studies, and Decolonial theory. My work cultivates the curational roots at the heart of camp and different theoretical approaches to relationality in order to foreground the emergence of curational camp methodologies and approaches to art as they manifest in the work of Sadie Benning, G.B Jones, Kaucyila Brooke and Jane Cottis, Cheryl Dunye, and Vaginal Davis. -

The Renaissance Society Presents Shared Eye, a New Installation by Artist Sadie Benning

The Renaissance Society presents Shared Eye, a new installation by artist Sadie Benning. In this series of mixed-media panels, images are layered and interpolated, suggesting the complexities of representation inherent in visual communications Shared Eye consists of 40 panels that have been cut up and re-assembled. Composed of mounted digital snapshots, found photographs, objects, and painted elements, the pieces hover between mediums, often starting as a drawing and evolving into a sculptural wall work. The frame ratio of each panel and the number of panels in each of 15 sequences has been determined by the mathematical parameters of Blinky Palermo’s 1976 work To the People of New York City: Palermo’s installation is composed of 40 seemingly non-representational paintings presented in a rhythmic pattern of scale, proximity, and number. In Shared Eye, the juxtaposition of images produces a fragmented but intensely felt friction, similar to what we experience in dreams, or while thinking, when the images stored in our minds unfold and forge new connections to produce narratives. The title of Benning’s installation emphasizes an understanding of vision as a shared act and of perception as a construct built upon a spectrum of separate, converging, associative, and at times conflicting components. This “shared eye” has a certain utility, but it can also manifest as feelings of discomfort, anger, and acts of violence. Shared Eye highlights how internalized and automatic the pervasive surveillance-like affect of Capitalism and its attendant structures of patriarchy, misogyny, racism, and xenophobia can become. The artist illustrates, in both poetic and critical terms, this associative construction of meaning: for Benning, it is imperative to name and disrupt this system of organizing information, as it relates to this particular moment of deep political uncertainty. -

New Queer Cinema, a 25-Film Series Commemorating the 20Th Anniversary of the Watershed Year for New Queer Cinema, Oct 9 & 11—16

BAMcinématek presents Born in Flames: New Queer Cinema, a 25-film series commemorating the 20th anniversary of the watershed year for New Queer Cinema, Oct 9 & 11—16 The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Brooklyn, NY/Sep 14, 2012—From Tuesday, October 9 through Tuesday, October 16, BAMcinématek presents Born in Flames: New Queer Cinema, a series commemorating the 20th anniversary of the term ―New Queer Cinema‖ and coinciding with LGBT History Month. A loosely defined subset of the independent film zeitgeist of the early 1990s, New Queer Cinema saw a number of openly gay artists break out with films that vented anger over homophobic policies of the Reagan and Thatcher governments and the grim realities of the AIDS epidemic with aesthetically and politically radical images of gay life. This primer of new queer classics includes more than two dozen LGBT-themed features and short films, including important early works by directors Todd Haynes, Gus Van Sant, and Gregg Araki, and experimental filmmakers Peggy Ahwesh, Luther Price, and Isaac Julien. New Queer Cinema was first named and defined 20 years ago in a brief but influential article in Sight & Sound by critic B. Ruby Rich, who noted a confluence of gay-oriented films among the most acclaimed entries in the Sundance, Toronto, and New Directors/New Films festivals of 1991 and 1992. Rich called it ―Homo Pomo,‖ a self-aware style defined by ―appropriation and pastiche, irony, as well as a reworking of history with social constructionism very much in mind . irreverent, energetic, alternately minimalist and excessive.‖ The most prominent of the films Rich catalogued were Tom Kalin’s Leopold and Loeb story Swoon (the subject of a 20th anniversary BAMcinématek tribute on September 13) and Haynes’ Sundance Grand Jury Prize winner Poison (1991—Oct 12), an unpolished but complex triptych of unrelated, stylistically diverse, Jean Genet-inspired stories. -

REFORMULATING the RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT: GRRRL RIOT the REFORMULATING : Riot Grrrl, Lyrics, Space, Sisterhood, Kathleen Hanna

REFORMULATING THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT: SPACE AND SISTERHOOD IN KATHLEEN HANNA’S LYRICS Soraya Alonso Alconada Universidad del País Vasco (UPV/EHU) [email protected] Abstract Music has become a crucial domain to discuss issues such as gender, identities and equality. With this study I aim at carrying out a feminist critical discourse analysis of the lyrics by American singer and songwriter Kathleen Hanna (1968-), a pioneer within the underground punk culture and head figure of the Riot Grrrl movement. Covering relevant issues related to women’s conditions, Hanna’s lyrics put gender issues at the forefront and become a sig- nificant means to claim feminism in the underground. In this study I pay attention to the instances in which Hanna’s lyrics in Bikini Kill and Le Tigre exhibit a reading of sisterhood and space and by doing so, I will discuss women’s invisibility in underground music and broaden the social and cultural understanding of this music. Keywords: Riot Grrrl, lyrics, space, sisterhood, Kathleen Hanna. REFORMULANDO EL MOVIMIENTO RIOT GRRRL: ESPACIO Y SORORIDAD EN LAS LETRAS DE KATHLEEN HANNA Resumen 99 La música se ha convertido en un espacio en el que debatir temas como el género, la iden- tidad o la igualdad. Con este trabajo pretendo llevar a cabo un análisis crítico del discurso con perspectiva feminista de las letras de canciones de Kathleen Hanna (1968-), cantante y compositora americana, pionera del movimiento punk y figura principal del movimiento Riot Grrrl. Cubriendo temas relevantes relacionados con la condición de las mujeres, las letras de Hanna sitúan temas relacionados con el género en primera línea y se convierten en un medio significativo para reclamar el feminismo en la música underground. -

Download Artist Bios

REFLECTING ABSTRACTION April 14 - May 14, 2011 Participants SADIE BENNING Sadie Benning was born in Madison, Wisconsin in 1973. She received her M.F.A. from Bard College in 1997. Her videos have been exhibited internationally in museums, galleries, universities and film festivals since 1990 with select solo exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, The Whitney Museum of American Art, The Film Society of Lincoln Center, Centre Georges Pompidou, and Hallwalls Contemporary Arts Center among other venues. Her work is in many permanent collections, including those of the Museum of Modern art, The Fogg Art Musuem, and the Walker Art Center, and has been included in the following exhibitions: Annual Report: 7th Gwangju Biennale (2008); White Columns Annual (2007); Whitney Biennial (2000 and 1993); Building Identities, Tate Modern (2004); Remembrance and the Moving Image, Australian Centre for the Moving Image (2003); Video Viewpoints, Museum of Modern Art (2002); American Century, Whitney Museum of Modern Art (2000); Love’s Body, Tokyo Museum of Photography (1999); Scream and Scream Again: Film in Art, Museum of Modern Art Oxford (1996-7), and Venice Biennale (1993). Benning’s recent work has increasingly incorporated video installation, sound, sculpture, and drawing. Solo exhibitions include Wexner Center for the Arts (Sadie Benning: Suspended Animation, 2007), Orchard Gallery (Form of…a Waterfall, 2008), Dia: Chealsea (Play Pause, 2008) and The Power Plant (Play Pause, 2008). She is a former member and cofounder, with Kathleen Hanna and Johanna Fateman, of the music group Le Tigre. She has received grants and fellowships from Guggenheim Foundation, Andrea Frank Foundation, National Endowment of the Arts, and Rockefeller Foundation. -

Video Art at the Woman's Building

[From Site to Vision] the Woman’s Building in Contemporary Culture The [e]Book Edited by Sondra Hale and Terry Wolverton Stories from a Generation: Video Art at the Woman’s Building Cecilia Dougherty Introduction In 1994 Elayne Zalis, who was, at the time, the Video Archivist at the Long Beach Mu- seum of Art, brought a small selection of tapes to the University of California at Irvine for a presentation about early video by women. I was teaching video production at UC-Irvine at the time and had heard from a colleague that Long Beach housed a large collection of videotapes produced at the Los Angeles Woman’s Building. I mistakenly assumed that Zalis’s talk was based on this collection, and I wanted to see more. I telephoned her after the presentation. She explained that the tapes she presented were part of a then current exhibition called The First Generation: Women and Video, 1970-75, curated by JoAnn Hanley. She said that although the work from The First Generation was not from the Woman’s Building collection, the Long Beach Museum did in fact have some tapes I might want to see. Not only did they have the Woman’s Building tapes, but there were more than 350 of them. Moreover, I could visit the Annex at any time to look at them. I felt as if I had struck gold.1 Eventually I watched over fifty of the tapes, most of which are from the 1970s, and un- earthed a rich and phenomenal body of early feminist video work. -

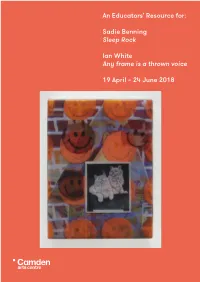

Educators' Resource: Sadie Benning and Ian White

An Educators’ Resource for: Sadie Benning Sleep Rock Ian White Any frame is a thrown voice 19 April – 24 June 2018 Sadie Benning Sleep Rock For this exhibition, Sadie Benning has created over 19 new wall-based works that occupy a hybrid space between painting, photography and sculptural relief. The title, Sleep Rock, evokes a dream state where perception is blurred by the merging of memory, vision, and association. Installed sequentially in Galleries 1 & 2, the works in the exhibition read with a filmic register, frame by frame – a picture can be read from a distance, or seen in detail close-up. There is an important operation of scale brought into play, both in the varying sizes of the panels and in Benning’s use of images. Scale also affects Benning’s use of materials in this body of work. Large-scale works are built through a process of fragmentation and reconstruction. The works originate as small drawings, which are projected and traced onto wooden panels. The panels are cut into pieces following the lines of the drawing. Benning applies layers of aqua- resin onto each piece and sands them until smooth before painting and then reassembling the components. The surface of the finished work has an ambiguous materiality, sometimes resembling ceramic or leather. For the small-scale works, Benning has developed a new approach that involves slowly layering resin and composite transparencies, with painted and photographic cut-out elements. Sadie Benning (b. 1973 Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) lives and works in New York, USA. Benning began creating visual works at the age of 15 and left school aged 16. -

Sadie Benning Excuse Me Ma'am

kaufmann repetto Sadie Benning Excuse Me Ma’am opening September 22, 7 pm Sadie Benning started making experimental videos as a teenager in 1988. The low-fi, black and white videos explored aspects of identity, language and memory. Improvising with materials that were immediately available at the time, Benning fragmentally constructed moving images from found objects, drawings, text, performance and personally shot footage. The form, content and poetics explored in the earlier video works has expanded over the past two decades, continuing to wrestle with evolving political, conceptual and material questions. The body of work comprised in Excuse Me Ma’am features paintings which include digital photographs of intimately scaled notebook drawings. These quick pencil sketches have been upscaled in size, accentuating the noise and color spectrum of its original while retaining a kind of directness and fragility. The phrase Excuse Me Ma’am encapsulates the moment of being signified within a binary gender narrative, a moment experienced many times within a single day. These works explore the complicated relationship between the body and how it is named within the culture, and the interminable desire to exist outside of the constructed polarities of male and female. The form of these works is not easy to categorize. Combining painting, photography, drawing and sculpture, we ask ourselves: What is this thing, what is it made of? How is a painting a painting and also not a painting? What goes unseen? What is distorted by the eye? Benning urges us to approach gender in this same manner, broadening the categories to the point of shattering them. -

Music: Popular by Carla Williams

Music: Popular by Carla Williams Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered persons have had tremendous influence on popular music. As artists, muses, producers, composers, publishers, and every role in between, gays and lesbians have left an indelible impression upon the popular consciousness through their contributions to music. Their presence can be found everywhere, from out lesbian Vicki Randle playing percussion and singing in the Tonight Show band, to two men dressed as cops and kissing in a Marilyn Manson music video. Top: A photograph of k. d. lang by Jeri Heiden. Popular music has always had a gay and lesbian presence, but it has not always been Above: Rob Halford of out in the open. Nor has there been an entirely linear progression from total Judas Priest on stage in Birmingham, England in repression to today's relative openness. For example, several well known gay men, 2005. Photograph by bisexuals, and lesbians of the 1920s who lived their lives openly were forced back into Andrew Dale. the closet when social mores shifted. For decades, their sexuality was obscured and Image of k. d. lang hidden. courtesy Sacks and Company. In the music industry, it is not only the "talent" who are homosexual: for example, David Geffen, founder of Geffen Records, is one of the most successful producers in recording history and one of the wealthiest men in entertainment. Similarly, Jann Wenner, founder of Rolling Stone magazine, long considered the rock and roll bible, is now involved in a homosexual relationship. -

SADIE BENNING Born: 1973, Madison, WI Lives and Works In

SADIE BENNING Born: 1973, Madison, WI Lives and works in Arizona EDUCATION 1997 MFA, Milton Avery School of Art at Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY SELECTED SOLO AND TWO PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2020 Pain Thing 2, Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York, NY Pain Thing, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, OH Sadie Benning: This is Real, Vielmetter Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 2018 Sleep Rock, Camden Arts Centre, London, UK 2017 Blinded by the Light, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Culver City, CA 2016-17 Shared Eye, Renaissance Society, Chicago, IL; Kunsthalle Basel, Basel, Switzerland 2016 Green God, Callicoon Fine Arts and Mary Boone Gallery, New York, NY L'oeil de l'esprit, Air de Paris, Paris, France Excuse Me Ma’am, Kaufmann Repetto, Milan, Italy 2015 Fuzzy Math, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Culver City, CA 2014 Patterns, Callicoon Fine Arts, New York, NY 2013 War Credits, Callicoon Fine Arts, New York, NY 2011 Transitional Effects, Participant Inc., New York, NY 2009-7 Play Pause, The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY; The Power Plant, Toronto, Canada (2008); Dia Foundation for the Arts, New York, NY (2007) 2007 Form of…a Waterfall, Orchard Gallery, New York, NY Sadie Benning: Suspended Animation, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, OH 2005 Sadie Benning’s Early Pixelvision Videos, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN 2004 Sadie Benning Retrospective Series, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, OH 1991 Sadie Benning, Randolph Street Gallery, Chicago, IL Sadie Benning Videos, Museum of Modern Art, New York, -

Sadie Benning

kaufmann repetto SADIE BENNING Born 1973 in Madison, WI. Lives and works in New York. Selected Solo Exhibitions 2018 Sleep rock, Camden Arts Centre, London 2017 Shared Eye, Kunsthalle Basel, CH Blinded by the Light, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Los Angeles, CA 2016 Shared Eye, The Renaissance Society, Chicago, IL Excuse Me Ma’am, kaufmann repetto, Milan L’oeil de l’esprit, Air de Paris, Paris Green God, Callicoon Fine Arts and Mary Boone, NY 2015 Fuzzy Math, Susanne Vielmetter, Los Angeles, CA 2014 Patterns, Callicoon Fine Arts, NY 2013 War Credits, Callicoon Fine Arts, NY 2011 Transitional Effects, Participant Inc., NY 2009 Play Pause, The Whitney Museum of American Art, NY 2008 Play Pause, The Power Plant, Toronto, CA 2007 Form of... a Waterfall, Orchard Gallery, NY Play Pause, Dia Foundation for the Arts, NY Sadie Benning: Suspended Animation, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, OH 2005 Sadie Bennings Early Pixelvision Videos, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN 2004 Sadie Benning Retrospective Series, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, OH Selected Group Exhibitions and Screenings 2018 Photography Today: Private Public Relations, Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, Germany 2017 Women to the Front, Lumber Room, Portland, OR Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon, New Museum, New York, NY Press Your Space Face Close to Mine, curated by Aaron Curry, The Pit, Los Angeles, CA Blinded by the light, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Culver City 2016 Figurative Geometry, curated by Bob Nickas, Collezione Maramotti, Reggio -

CV Sadie Benning

SADIE BENNING: ARTIST CV Born 1973 in Madison, Wisconsin. She lives and works in New York, NY. EDUCATION 1997 Master of Fine Arts, Milton Avery School of the Arts, Bard College, Annandale-on-the-Hudson, NY SELECTED EXHIBITIONS 2011 “Sadie Benning”, solo exhibition, Participant Inc., NYC “Reflecting Abstraction”, Vogt Gallery, NYC 2009 “Play Pause,” solo exhibition, The Whitney Museum of American Art, NYC 2008 “Play Pause,” solo exhibition, Power Plant Gallery, Toronto “Play Pause,” Gwangju Biennale, South Korea 2007 “Play Pause,” Dia Foundation for the Arts, NYC “Form of a Waterfall,” solo exhibition of drawings, video, and sound, Orchard Gallery, NY “Sadie Benning: Suspended Animation,” Solo Exhibition of Paintings and Video, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, OH “Animated Painting,” San Diego Museum of Art, CA 2006 “MoMA: American Documentary, 1920’s to Now,” Taiwan International Documentary Festival, Taipei, Taiwan 2005 “Bidibidobidiboo,” Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin, Italy “Sadie Benning’s Early Pixelvision Videos,” Installation, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN “To Die of Love (Voluntary Permanence), “Museo Universitario de ciencias y arte,” Rome, Italy 2004 “Sadie Benning Retrospective Series,” Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, OH “Building Identities,” Tate Modern, London, UK 2003 Women’s International Film Festival, Seoul, Korea “Remembrance + the Moving Image,” Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Melbourne Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, WI “Video Viewpoints: A Selection From the Last Decade,” Museum