Coordinated Public Transit–Human-Services Transportation Plan for Delaware

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DART Resumes Full Bus Service Levels, Front Door Boardings and Fare Collection on Monday, June 1

Delaware Transit Corporation (DTC) News Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Contact: DTC Public Affairs May 26, 2020 [email protected] (302) 576-6005 DART Resumes Full Bus Service Levels, Front Door Boardings and Fare Collection on Monday, June 1 DART will resume full-service levels starting Monday, June 1, with the exception of the seasonal Beach Bus services in the resort areas. Front door boardings and fare collection will also be reinstated. To promote the use of contactless, cashless fare payments using the DART Pass mobile payment app, DART is offering further discounts on Daily, 7-Day and 30-Day passes on the app. For customers not using the app, DARTCard and Pass Sales will resume at the following DART locations: Wilmington Transit Center, Amtrak Station, DART Administration Buildings in Wilmington and Dover, 718 N. Market Street in Wilmington, Rehoboth Park & Ride, and Lewes Transit Center. See Ticket Sales for other locations. Paratransit fares will be charged; however, there will be no cash or tickets accepted or handled by the Operator. Customers are encouraged to use DART Pass to pay their fare. Those choosing not to use the fare payment app will be billed for their trips. The safety and well-being of our customers and employees is our top priority. We know the importance of connecting people to their destinations, safely, and efficiently. DART continues to limit the number of passengers allowed on each bus at any given time, based on bus seating capacity. Riders must wear face coverings when riding any DART bus, fixed route or paratransit. Those not wearing face coverings will not be allowed to board the bus. -

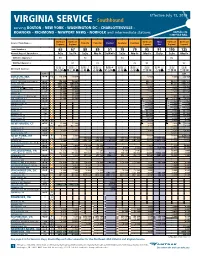

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

New Castle County (Newark

l Continuation of bus routes from New Castle County Map A l Casino at Delaware Park llllll Transit Routes / Legend llllll 9 5 Racing/Slots/Golf llllll 95 lllll lllll lllll Corp. Commons Fairplay Train Station lllll l 2 Concord Pike (wkday/wkend) 6 llll 5 l News Journal 295 llll 72 P llll Cherry La Delaware Memorial Bridge 4 Prices Corner/Wilmington/Edgemoor (wkday/wkend) lll ll W. Basin Rd 273 City of Newark ll d bl lv l 5 ll B Maryland Avenue (wkday/wkend) ll s & Newark Transit Hub ll n lll o Department lll Christiana Mall m 6 Kirkwood Highway (wkday/wkend) lll om l e ll C Southgate Ind. v of Corrections See City of Newark ll A O llRlldll 4 g nl Park & Ride Park e letowl S l lll j l 8 l t 8th Street and 9th Street (wkday/Sat) ll a New Castle Riveredge Map ll s l l l l a llll d e County Airport Wilmington Industrial Park l m ll See Christiana Area C 9 llll R Ch Zenith Boxwood Rd/Broom St/Vandever Avenue (wkday/Sat) ll M l u College ll l w ll i C 273 rc 295 l e ll a H Map h Century Ind. l h m r ll t N ll r u u a ll o n n l Park Newark/Wilmington (wkday/Sat) l r d l S t 58 s 141 w Suburban ll s c d R e l . e t R l h R l s r d l C h Plaza ll C n o New Castle Airport R R l o a p Washington Street/Marsh Road (wkday/Sat) l E. -

Newark-Area Transit Study Draft Report – June 2019

Newark-Area Transit Study Draft Report – June 2019 Newark-Area Transit Study DRAFT REPORT June 2019 Newark Transit Improvement Partnership 0 Newark-Area Transit Study Draft Report – June 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................................2 Chapter 1. Introduction ..............................................................................................................................................4 Study Purpose .........................................................................................................................................................4 Goals & Objectives .................................................................................................................................................4 Participating Agencies ............................................................................................................................................4 Study Process ..........................................................................................................................................................4 Chapter 2. Existing Conditions ....................................................................................................................................6 Transit and Market Need Analysis ..........................................................................................................................6 Newark-Area Transit Systems -

Delaware Department of Transportation Final Title VI Review

Delaware Department of Transportation Title VI Compliance Review Final Report June 2019 Title VI Compliance Review Final Report: DelDOT June 2019 This page intentionally left blank to facilitate duplex printing. Title VI Compliance Review Final Report: DelDOT June 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................... 1 1. General Information ............................................................................................................... 3 2. Jurisdiction and Authorities .................................................................................................... 5 3. Purpose and Objectives .......................................................................................................... 7 3.1 Purpose ............................................................................................................................................. 7 3.2 Objectives ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4. Introduction to the Delaware Department of Transportation .............................................. 9 4.1 DelDOT Description and Organizational Structure ............................................................... 9 5. Scope and Methodology ....................................................................................................... 13 5.1 Scope .............................................................................................................................................. -

Smart Location Database Technical Documentation and User Guide

SMART LOCATION DATABASE TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION AND USER GUIDE Version 3.0 Updated: June 2021 Authors: Jim Chapman, MSCE, Managing Principal, Urban Design 4 Health, Inc. (UD4H) Eric H. Fox, MScP, Senior Planner, UD4H William Bachman, Ph.D., Senior Analyst, UD4H Lawrence D. Frank, Ph.D., President, UD4H John Thomas, Ph.D., U.S. EPA Office of Community Revitalization Alexis Rourk Reyes, MSCRP, U.S. EPA Office of Community Revitalization About This Report The Smart Location Database is a publicly available data product and service provided by the U.S. EPA Smart Growth Program. This version 3.0 documentation builds on, and updates where needed, the version 2.0 document.1 Urban Design 4 Health, Inc. updated this guide for the project called Updating the EPA GSA Smart Location Database. Acknowledgements Urban Design 4 Health was contracted by the U.S. EPA with support from the General Services Administration’s Center for Urban Development to update the Smart Location Database and this User Guide. As the Project Manager for this study, Jim Chapman supervised the data development and authored this updated user guide. Mr. Eric Fox and Dr. William Bachman led all data acquisition, geoprocessing, and spatial analyses undertaken in the development of version 3.0 of the Smart Location Database and co- authored the user guide through substantive contributions to the methods and information provided. Dr. Larry Frank provided data development input and reviewed the report providing critical input and feedback. The authors would like to acknowledge the guidance, review, and support provided by: • Ruth Kroeger, U.S. General Services Administration • Frank Giblin, U.S. -

Cardinal Schedule

SM Effective October 5, 2020 CARDINAL serving NEW YORK - WASHINGTON, DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - WHITE SULPHUR SPRINGS - CHARLESTON - CINCINNATI - INDIANAPOLIS - CHICAGO and intermediate stations Amtrak.com BOOK TRAVEL, CHECK TRAIN STATUS, ACCESS YOUR ETICKET AND MORE THROUGH THE Amtrak app. 1-800-USA-RAIL 51 3Train Number4 50 CARDINAL As indicated 3 4 As indicated ROUTE MAP and SYMBOLS in column Normal Days of Operation in column R s d y R s d y l å O 3On Board Service4 l å O Read Down Mile Symbol Read Up 6 5 Dyer, INLafayette,Indianapolis, IN Cincinnati, INSouth OH Portsmouth/SouthHuntington,Montgomery, WVPrince, Shore, WV WVAlderson, KY Clifton WV Forge,Charlottesville, VAManassas,Washington, VA VA Wilmington, DCTrenton, DENew NJ York, NY l6 45A WeFrSu 0 Dp New York, NY (ET) ∑w-u Ar l9 58P WeFrSu –Penn Station Chicago, IL Newark, NJ l ∑w- l Rensselaer, IN Maysville,Ashland, KY KY Hinton, WV Staunton,Culpeper, VA Alexandria, VABaltimore, VA MD R7 05A WeFrSu 10 Newark, NJ p D9 38P WeFrSu Crawfordsville,Connersville, IN IN Charleston,Thurmond, WV WV Philadelphia, PA ∑w- 7 42A WeFrSu 58 Trenton, NJ D9 02P WeFrSu White Sulphur Springs, WV l8 18A WeFrSu 91 Philadelphia, PA ∑w-u lD8 26P WeFrSu –30th Street Station l8 47A WeFrSu 116 Wilmington, DE ∑v- lD8 05P WeFrSu CHICAGO l9 35A WeFrSu 185 q Baltimore, MD–Penn Station ∑w- lD7 16P WeFrSu NEW YORK l ∑w- l 10 15A WeFrSu 225 Ar Washington, DC u Dp D6 44P WeFrSu INDIANAPOLIS l11 00A WeFrSu Dp –Union Station Ar lD6 19P WeFrSu l11 19A WeFrSu 233 Alexandria, VA ∑w- Ar lD5 59P WeFrSu 11 52A WeFrSu 258 Manassas, VA > p 5 10P WeFrSu 12 25P WeFrSu 293 Culpeper, VA >v 4 35P WeFrSu q Cardinal ® l1 43P WeFrSu 340 Ar Charlottesville, VA ∑w- Dp l3 19P WeFrSu Other Amtrak Train Routes l1 52P WeFrSu Dp b Richmond—see page 2 Ar l3 10P WeFrSu 2 54P WeFrSu 379 Staunton, VA > p 2 03P WeFrSu 4 13P WeFrSu 437 Clifton Forge, VA (Homestead) > 12 44P WeFrSu SYMBOLS KEY 5 05P WeFrSu 472 White Sulphur Springs, WV > 11 39A WeFrSu D Stops only to discharge u Amtrak Lounge available. -

Chapter 3 Transportation

Chapter 3 Transportation Overview The movement of people and goods is an important concern to the Town of North East, making the Transportation element especially significant. Providing a safe and efficient transportation network with minimal disruption can sometimes be difficult to achieve. The Transportation element must be closely coordinated with other elements of the Plan to ensure that transportation plans and policies complement and promote those of other sections. The North East Municipal Growth Element identifies suitable areas for municipal expansion and establishes a two-tiered priority for growth and development. Those priority areas and the uses identified for those tracts combine to determine where additional study and evaluation of existing and future transportation capacity should be focused. The goals and objectives listed below provide guidance regarding the Town’s desire to enhance the safety, convenience, and functionality of existing facilities and future system expansions and improvements. Building upon the goals and policies in the 1992 Economic Growth, Resource Protection, and Planning Act, more recent State legislation1 addressed priorities for public investments in infrastructure; linking infrastructure capacity to priorities for targeted future growth; and expanded planning visions that address quality of life, sustainability, public participation and community design. A package of Bills, collectively known as the Smart and Sustainable Growth Act of 2009, strengthened required consistency between Plan content and implementation ordinances. The 2009 Act requires documentation about local efforts to address Plan goals and implementation of the twelve Planning Visions through revised annual reporting to the Maryland Department of Planning (MDP) on a uniform set of smart growth measures and indicators. -

COT Meeting August 14, 2017

Department of Transportation COT Meeting August 14, 2017 Approval of the Agenda Approval of the Minutes Secretary’s Update ◦ Financial Update ◦ Transit Center P3 (Action Item) ◦ Delaware Transit Corporation Update Review Draft FY19 – FY24 CTP ◦ Approve Draft for Public Comment (Action Item) US113 Update Public Comment 2 Secretary’s Update Every Trip ◦ We strive to make every trip taken in Delaware safe, reliable and convenient for people and commerce. Every Mode ◦ We provide safe choices for travelers in Delaware to access roads, rails, buses, airways, waterways, bike trails, and walking paths. Every Dollar ◦ We seek the best value for every dollar spent for the benefit of all. Everyone ◦ We engage and communicate with our customers and employees openly and respectfully as we deliver our services. 4 Msc. Revenue, DelDOT OP $13.5 (GF), $5.0 15% I-95 Tolls, $135.8 Federal Funds, 7% $297.7 33% SR-1 Tolls, $62.8 Bond Proceeds, 24% $18.9 DMV Revenues, Fare Box, 14% $216.6 $26.8 Motor Fuel Tax, Interest, $3.0 $128.0 Trust Fund Revenues Unaudited FOECASTED Revenues FY10 FY11 FY12 FY13 FY14 FY15 FY16 FY17 FY18 FY19 FY20 FY21 FY22 FY23 FY24 Motor Fuel Tax 115.7 116.6 115.9 115.0 116.9 119.6 126.5 132.1 128.0 126.9 125.9 124.9 123.9 122.9 121.9 Toll Roads 164.9 160.3 162.0 166.3 170.0 176.1 192.3 195.0 198.6 201.2 203.2 205.1 207.2 209.2 210.8 DMV Revenues 125.8 140.1 142.7 150.5 160.3 171.0 198.1 210.5 216.6 221.4 226.1 231.3 236.2 241.3 246.6 406.4 417.0 420.6 431.8 447.2 466.7 516.9 537.6 543.2 549.5 555.2 561.3 567.3 573.4 579.3 $260.0 -

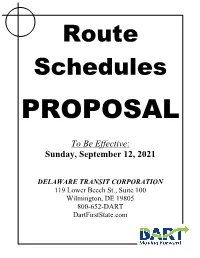

To Be Effective: Sunday, September 12, 2021

Route Schedules PROPOSAL To Be Effective: Sunday, September 12, 2021 DELAWARE TRANSIT CORPORATION 119 Lower Beech St., Suite 100 Wilmington, DE 19805 800-652-DART DartFirstState.com Virtual Public Hearing Workshop Delaware Transit Corporation (DTC) invites you to join a virtual Public Hearing Workshop via Zoom to provide input and comments on proposed changes to DART Statewide Bus Services to become effective September 12, 2021. Tuesday, June 22, 2021 4 PM to 6 PM The Zoom link to the virtual workshop, proposal summary, schedules and maps are available at DartFirstState.com or by scanning this QR code. The virtual workshop will begin with a presentation of the proposed service changes, followed by a question and answer period (approx. 30 minutes). The remainder of the workshop will be followed by public testimony for those wishing to provide public comments. All content for the virtual public hearing workshop will be recorded and posted to DartFirstState.com; public testimony will be transcribed by a hearing reporter. Closed Captioning is available through Zoom. If an accommodation such as a language translator is needed, please call (302) 760-2827, one week in advance. For your convenience, a summary of proposed service changes, maps and specific schedules are available for review online at DartFirstState.com, at the reception desks of DART Administrative Offices in Wilmington and Dover, and at the Lewes Transit Center. Attendees may also provide comments via email, online comment form, calling 1-800-652-DART (3278), option 2, or by mail sent to: DART Public Hearing, 119 Lower Beech St., Wilmington, DE 19805-4440 or online at DartFirstState.com/publichearing by June 25, 2021. -

DART First State Great Beginnings

Delaware Transit Corporation DART First State Great Beginnings Delaware Coach Co. - 1864 GWTA - 1969 DART - 1971 DART First State - 1995 Our Mission The Mission of the Delaware Transit Corporation is to design and provide the highest quality public transportation services that satisfy the needs of the customer and the community. Service Overview Operating Division of DelDOT Services statewide Over 224 fixed route buses operate 69 bus routes (Statewide) Over 284 paratransit buses Contract commuter rail service between Delaware & Philadelphia Mobility programs Service Characteristics New Castle County Operate 47 bus routes Paratransit service covers entire County Rail service Population of 534,634 County size - 426 square miles County mix of urban & industrial Rider Demographics New Castle County • 79.4% commute to and from work alone • 10.1% carpool Age 15.3% 35-44 • 3.6% use public transit 12.5% 25-34 •29.5% BA degree or higher Gender 54.4% Female No Vehicle Available 48.6% Male 32.9% Service Characteristics Kent County Operate 14 bus routes Paratransit service covers entire County Population of 157,741 County size - 591 square miles County mix of urban & rural Rider Demographics Kent County • 33% commute to and from work Age • 61% ride four or five days a week 16.2% 35-44 • 18.6% BA degree or higher 13.5% 25-34 Gender No Vehicle Available 51.8% Female 52.1% 48.2% Male Service Characteristics Sussex County Operate 7 bus routes Paratransit service covers entire County Population of 192,747 County size - 938 square -

Special Wilmington/Newark Line Schedule

www.septa.org T.T.6 WIL-4 Supplement SCIP Supplement WIL-4 T.T.6 7/19 SEPTA © TDD/TTY: 215-580-7853 TDD/TTY: TO MARCUS HOOK / WILMINGTON TO CENTER CITY 215-580-7800 Service: Customer BRS = Broad-Ridge Spur Broad-Ridge = BRS Zone Zone Fare Fare C C BSL = Broad Street Line Street Broad = BSL 3 3 2 2 3 4 4 3 3 3 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 3 4 4 MFL = Market-Frankford Line Market-Frankford = MFL Amtrak Lower Level Lower Amtrak otherwise noted otherwise Services Services * All Connecting Services are SEPTA Bus, Trolley or High Speed Rail unless Rail Speed High or Trolley Bus, SEPTA are Services Connecting All * • 30th Street Station Street 30th • Darby • 30th Stations Wilmington Stations Wilmington Claymont Marcus Hook Marcus Highland AvenueEddystone Crum Lynne 7:14 Park Ridley 8:14 Park-MooreProspect 9:14Norwood 10:14 11:14 7:04Glenolden 12:14 1:14 8:04Folcroft 2:14Sharon Hill 9:04 3:14 10:04Curtis Park 4:14 11:04 12:04 5:14Darby 1:04 6:14 2:04 7:14 3:04 8:14 4:04 9:14 5:04 11:12 6:04 7:04 8:04 9:04 11:01 Chester T.C. Chester Darby Curtis Park Sharon Hill Glenolden Norwood Park-MooreProspect 7:24Crum Lynne 8:24Eddystone T.C. Chester 9:23 10:23Highland Avenue 11:23 12:23 Hook Marcus 1:23Claymont 2:23 3:23 7:13 4:23 8:13 5:23 6:23 9:13 7:23 10:13 11:13 8:23 12:13 1:13 9:23 2:13 9:53 3:13 4:13 12:09 5:13 6:13 7:13 8:13 9:13 9:43 11:59 Folcroft Park Ridley 30th * only.