ARAIZA-DISSERTATION-2016.Pdf (1.187Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Houston Area Rainbow Collective History Community-Led Archives by Christian Kelleher, with Larry Criscione, J.D

FROM THE ARCHIVES Houston Area Rainbow Collective History Community-led Archives By Christian Kelleher, with Larry Criscione, J.D. Doyle, Alexis Melvin, Judy Reeves, and Cristan Williams ust over a decade ago Houston Public Library’s Jo by Charles Gillis and Kenneth Adrian Cyr in Fort Worth’s JCollier brought together a group of local lesbian, gay, Awareness, Unity, and Research Association during the early bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community historians, 1970s. Storage is often a challenge for thriving community archivists, and scholars as part of the library’s LGBT speak- archives, and the Texas Gay Archive had moved to Houston er series. Recognizing commonalities and opportunities in in Gillis’ famous Wilde ’N’ Stein bookstore in the later 1970s, their diverse organizations and programs, the group formed then was maintained by the nonprofit gay social service Houston Area Rainbow Collective History (ARCH) as a organization Integrity (later Interact) Houston, and finally space for discussion, collaborative planning, and news shar- merged with the MCCR library.3 ing. Houston has long had a vibrant and influential LGBT After Charles Botts died in 1994, volunteer Larry community, and the individuals and organizations that met Criscione led the efforts to preserve and build the collec- as ARCH have taken on the responsibility to collect, pre- tion through 2012, when the church that housed the library serve, and share their community’s history.1 finally needed to reclaim the space it occupied. Jimmy Community-led archives are essential to the preservation of unique historical collections of books, archives, and artifacts that mainstream government or academic archives have typically neglected or undervalued. -

Mexican American Resource Guide: Sources of Information Relating to the Mexican American Community in Austin and Travis County

MEXICAN AMERICAN RESOURCE GUIDE: SOURCES OF INFORMATION RELATING TO THE MEXICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY IN AUSTIN AND TRAVIS COUNTY THE AUSTIN HISTORY CENTER, AUSTIN PUBLIC LIBRARY Updated by Amanda Jasso Mexican American Community Archivist September 2017 Austin History Center- Mexican American Resource Guide – September 2017 1 INTRODUCTION The purpose of the Austin History Center is to provide customers with information about the history and current events of Austin and Travis County by collecting, organizing, and preserving research materials and assisting in their use so that customers can learn from the community’s collective memory. The collections of the AHC contain valuable materials about Austin and Travis County’s Mexican American communities. The materials in the resource guide are arranged by collection unit of the Austin History Center. Within each collection unit, items are arranged in shelf-list order. This guide is one of a series of updates to the original 1977 version compiled by Austin History staff. It reflects the addition of materials to the Austin History Center based on the recommendations and donations of many generous individuals, support groups and Austin History Center staff. The Austin History Center card catalog supplements the Find It: Austin Public Library On-Line Library Catalog by providing analytical entries to information in periodicals and other materials in addition to listing individual items in the collection with entries under author, title, and subject. These tools lead to specific articles and other information in sources that would otherwise be very difficult to find. It must be noted that there are still significant gaps remaining in our collection in regards to the Mexican American community. -

Lenten Journey

March 9, 2014 + Opening Song Lenten When We All Get To Heaven Journey Sing the wondrous love of Jesus; Well, here we are Sing his mercy and his grace. again. It is Lent. Ash In the mansions bright and blessed Wednesday begins a forty-day journey He'll prepare for us a place. (plus Sundays) to Easter. This season When we all get to heaven, in the life of the What a day of rejoicing that will be! Church is fashioned When we all see Jesus, after Jesus' forty days We'll sing and shout the victory! in the wilderness, where he fasted and While we walk the pilgrim pathway, prayed and struggled Clouds will overspread the sky; with temptation in But when traveling days are over, an effort to discern his true relationship Not a shadow, not a sigh. to God. Each year, Christians are called (Chorus) to slow the pace of their hectic lives Let us then be true and faithful, and enter into forty Trusting, serving every day; days of introspection Just one glimpse of him in glory marked by spiritual Will the toils of life repay. disciplines such as prayer, almsgiving, (Chorus) and fasting in order to discern our true relationship to God. Onward to the prize before us! Soon his beauty we'll behold; In the history of the Soon the pearly gates will open; Christian Church, We shall tread the streets of gold. the way people have made this Lenten (Chorus) journey is to 'give up' or 'take on' certain Words and Music by Eliza Edmunds Stites Hewitt and Emily Divine Wilson things. -

Congressional Record—House H2998

H2998 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE June 22, 2021 to support at least one or two. We will much remains to be done. It is an op- the Equality Act, including, of course, see what happens during the process of portunity each year to really celebrate you, Madam Speaker. amending and debating. the progress we have made and recom- So I am proud to be a part of a cau- What I would say to my friend is that mit ourselves to the work that re- cus that understands the fundamental it would be great if we could address mains. This year is no different. importance of recognizing the dignity every issue with both sides of the aisle In 2021, we come together on the floor and value of every person, and Pride engaging and offering amendments and of this House to celebrate Pride Month Month is about expressing that and af- restore regular order so that we can try with some very great highs and some firming that to all LGBTQ-plus people to get to the heart and the truth of very deep lows. Our community was all across this country and all across these issues. deeply impacted by COVID, both be- the world. We are never going to deal with our cause preexisting conditions added to Tonight, I am proud to have one of spending issues in this country if we people’s vulnerabilities, but also be- the co-chairs of the Equality Caucus, don’t sit down and roll our sleeves up, cause segments of our population al- MARK TAKANO, Chairman of the Vet- like a family or small business has to ready face isolation, which was made erans’ Affairs Committee, a member of do. -

GINA HINOJOSA DEMOCRAT Incumbent

2020 General Election FACEOFFWEBSITE BOOKLET OCCUPATION CONSULTANT MAJOR ENDORSEMENTS Proprietary Document, Please Share Appropriately 1 VOTERS, CANDIDATES, AND ELECTED OFFICIALS: It’s time to start gearing up for the General Election! In a year that has already seen huge numbers of voter turnout, even amid a pandemic, the Texas state election promises to be one for the history books. To help all Texans better understand the landscape of this November’s race, we have put together a high-level booklet of the candidates facing off for every elected state position. Within this booklet, you will find biographical informa- tion and quick facts about each candidate. It is our hope that you will find this information helpful leading up to, during, and after the election as you get to know your candidates and victorious elected officials better. If you have suggestions on how to improve this document or would like to make an addition or correction, please let us know at [email protected]. Best of luck to all of the candidates, David White CEO of Public Blueprint To Note: Biographical information was sourced directly from campaign websites and may have been edited for length. Endorsements will be updated as major trade associations and organizations make their general election choices. "Unknown Consultant" denotes that we did not find a political consultant listed in expenditures on campaign finance reports. PUBLIC BLUEPRINT • 807 Brazos St, Suite 207 • Austin, TX 78701 [email protected] • publicblueprint.com • @publicblueprint TABLE OF CONTENTS 04. TEXAS SENATE CANDIDATES 32. TEXAS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES CANDIDATES 220. STATEWIDE CANDIDATES WEBSITE OCCUPATION CONSULTANT 3 TEXAS SENATE CANDIDATES FOR STATE SENATOR 06. -

Forest Says “No” to Homophobia

FOREST SAYS “NO” FR TO HOMOPHOBIA EE Nottinghamshire’s Queer Bulletin June/July 2008 Number 42 In this edition: · Disgusting pornography · Green sheep · Flyswatters · Lang’s watershed · Artefacts · Death · Trim or extra large Also, we are already quivering with anticipation in advance of July’s Nottingham Pride Festival. Will the Pride Committee’s annual naked rain dance yet again ensure fair weather? (Be there … June 21st, Arboretum, midnight) If you have any information, news, gossip or libel, please send it to QB Lesbian and Gay Switchboard After the application of amazing powers of persuasion by Nottingham 7 Mansfield Road City Council, Nottingham Forest have given their considerable weight to Nottingham NG1 3FB a local poster campaign to tackle homophobic bullying in schools. The or e-mail poster’s launch was timed to coincide with IDAHO day - May 17th, the [email protected] International Day Against Homophobia. The deadline for the next edition By “Nottingham Forest”, we mean both the men’s and the women’s team. will be mid July 2008. As this will QB believes that they are the first UK teams to put their names and faces be the Pride edition, it will appear to this sort of publicity. Sport remains a largely homophobic zone and a little later than usual. old-style macho attitudes are more prevalent in football than in most sports. The Forest teams deserve congratulations and much respect for Switchboard is registered char- their courage. We can now add a further “well done” following Forest’s ity number 1114273 promotion to the Championship. -

Forging a New Path: Transgender Singers in Popular Music

POPULAR SONG AND MUSIC THEATER Robert Edwin, Associate Editor Forging a New Path: Transgender Singers in Popular Music Nancy Bos ome of the first issues that a cisgender voice teacher of transgen- der and gender nonconforming singers faces is finding role models and repertoire for the student. After all, with most students we have well established ideas of what their musical niche might be. But trans- Sgender or gender nonconforming singers might seem to bring an entirely blank slate, as if nobody had ever developed a following or composed songs as a transgender singer. Thankfully, that is not the case. There are talented transgender singers in almost every genre, and many people have cut paths for our students to explore. Nancy Bos Few people have more expertise on music of transgender performers than JD Doyle, archivist of music of LGBTQ performers spanning the last hundred years. His websites, Queer Music Heritage and JD Doyle Archives, are both sources of understanding, appreciation, and exposure for LGBTQ singers. JD has an uncomplicated way of shining light on appropriate repertoire: “[W]hat is queer music, and what makes it different, and the same, from what straight artists write and sing about? It’s the same because of course LGBT people write about relationships, falling in love, wanting to be in love, and losing love . .” Doyle offers a number of recommendations of artists to consider that I have supplemented. It is exciting to hear the authentic and meaningful music of these artists, some who sing from their hearts with insightful, serious lyrics about their transitions, some who perform songs that say nothing specific about their transitions, and others who use comedy and bring up the edgier side of their lives. -

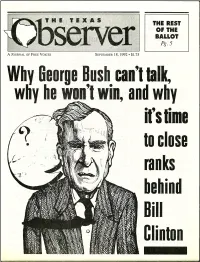

And Why Ifs Time to Close Ranks Behind Bill Clinton

THE REST OF THE BALLOT Pg. 5 A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES SEPTEMBER 18, 1992 • $1.75 Why .George ,llush can't. talk, Why 'ho-Von't win,;•-and why Ifs time to close ranks behind Bill Clinton DIALOGUE Ride That Horse A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES We will serve no group or party but will hew hard to the truth as we find it and the right as we see it. We are ALL IT MID-L1PE, CRISIS. Call it my bifoc- 2. Bill Clinton is not the lesser of two evils, dedicated to the whole truth, to human values above all Cular political vision. Say, "What a falling off the triumph of money in the Democratic Party interests, to the rights of human-kind as the foundation there was." But I just can't help wondering, as I or the new face on the old Democratic order. of democracy: we will take orders from none but our own sit here in my South Austin living room look- He is a candidate who has the potential to be the conscience, and never will we overlook or misrepresent the truth to serve the interests of the powerful or cater ing at the most recent Observers, when you guys best President we've had since the early days of to the ignoble in the human spirit. are going to stop taking the political temperature LBJ and, beyond that, since FDR because he Writers are responsible for their own work, but not at the wrong end of the horse. is someone who will be as good as we push him for anything they have not themselves written, and in pub- It was the cover of your Aug. -

The Power of Place in Houston

VOLUME 16 • NUMBER 2 • SPRING 2019 The Power of Place in Houston CENTER FOR PUBLIC HISTORY LETTER FROM THE EDITOR lations, performances, readings, lectures, and films from Finding Our “Place” in Houston February through May exploring Latino art as American In conversation and in historical art. Two articles examine women’s political place in the research “place” takes on a variety 1970s compared to today, demonstrating that women con- of meanings. It can represent a tinue to face many of the same battles. And the final feature physical location, a space within the article looks at Brownwood, Baytown’s “River Oaks” until community, a position in society, or Hurricanes Carla and Alicia wiped the neighborhood off the our diverse identities. Exploring map, forcing residents from their homes—their place. Houston history is more than just The departments also explore multiple meanings of place. looking at our location; we consider Baptist minister James Novarro became a leader in the all the things that make up our farmworkers minimum wage march in 1966 to demand la- environment, from the people to borers’ place at the bargaining table. Members of Houston’s Debbie Z. Harwell, Editor neighborhoods, schools, churches, LGBT community worked to preserve their history and tell businesses, and our culture. their story long before they had a public place to do so. The Through this broader examination of place, we learn who narratives of the offshore industry highlight industry pio- we are and how we connect to the big picture. neers who slogged through Louisiana marshlands to figure When I look at the cover photo of Leo Tanguma on the out how to drill underwater, enabling Houston to expand its ladder in front of Rebirth of Our Nationality, I marvel at the place as an energy capital. -

Queer Music History 101

| .. PDF created with the PDFmyURL web to PDF API! PDF created with the PDFmyURL web to PDF API! Back to QMH101 Start Website Version: Lesson, Part 1, 1926 - 1977, below Lesson, Part 2, 1973 - 1985 Recommended Books, and Notes Lesson, Part 1: 1926 - 1977 PDF created with the PDFmyURL web to PDF API! Audio Version Song List: Part 1 (59:16) Merrit Brunies & His Friar's Inn Orchestra - Troy Walker - Happiness Is a Thing Called Joe (1964) Masculine Women, Feminine Men (1926) Jackie Shane - Any Other Way (1963) Ma Rainey - Prove It On Me Blues (1926) Billy Strayhorn - Lush Life (1964) Bessie Jackson (Lucille Bogan) - Frances Faye - Night And Day (1959) B.D. Woman's Blues (1935) Minette - LBJ, Don't Take My Man Away (1968) Frankie "Half-Pint" Jaxon - My Daddy Rocks Zebedy Colt - The Man I Love (1970) Me With One Steady Roll (1929) Love Is A Drag - My Man (1962) Bing Crosby - Ain't No Sweet Man Worth Mad About the Boy - Mad About the Boy (mid-60s) the Salt of My Tears (1928) Maxine Feldman - Angry Atthis (1972) Douglas Byng & Lance Lister - Cabaret Boys (1928) Madeline Davis - Stonewall Nation (1972) Jean Malin - I'd Rather Be Spanish Lavender Country - Back in the Closet Again (1973) PDF created with the PDFmyURL web to PDF API! Jean Malin - I'd Rather Be Spanish Lavender Country - Back in the Closet Again (1973) Than Manish (1931) Doug Stevens & the Outband - Out in the Bruz Fletcher - She's My Most Intimate Friend (1937) Country (1993) Noel Coward - Green Carnation (1933) The Faggot - Women With Women, Rae Bourbon - Let Me Tell You About -

UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A Woman's Place: Lesbian Feminist Conflicts in Contemporary Popular Culture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3qt0t1jv Author Pruett, Jessica Lynn Publication Date 2021 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE A Woman’s Place: Lesbian Feminist Conflicts in Contemporary Popular Culture DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Culture and Theory by Jessica Pruett Dissertation Committee: Professor Jonathan Alexander, Chair Professor Victoria E. Johnson Professor Jennifer Terry Professor Christine Bacareza Balance Professor Sora Y. Han 2021 © 2021 Jessica Pruett TABLE OF CONTENTS Page VITA vii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION viii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 Sounding Out: Olivia Records and the Soundtrack of the Women’s Music 15 Movement CHAPTER 2 Making Herstory: Lesbian Anti-Capitalism Meets the Digital Age 55 CHAPTER 3 “A Gathering of Mothers and Daughters”: Race, Gender, and the Politics of 92 Inclusion at Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival CHAPTER 4 Beyond One Direction: Lesbian Feminist Fandom Remakes the Boy Band 131 CONCLUSION 173 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to my committee chair, Professor Jonathan Alexander, for his intellectual generosity, faith in my abilities, and extensive feedback on previous drafts of this work. His enthusiasm for teaching, writing, and learning is infectious, and I have been lucky to witness it for the last six years. I would also like to thank my committee members, Professors Jennifer Terry, Victoria E. Johnson, and Christine Bacareza Balance. -

Looking for America DIALOGUE

GRADING LENA GUERRERO Pg. 5 A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES OCTOBER 2, 1992 • $1.75 Buscando las Americas Looking for America DIALOGUE Dissing Dissent whatever cow he pleases but keep that super- stition out of our public life, please. With I would like to dissent from Wayne Walther's yellow dog democrats like this, who needs • A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES dissent (Dialogue, TO 8/21/92). We will serve no group or party but will hew hard to the repugs? First of all, if he is saying abortion is mur- Michael Hardesty, Oakland, Calif. the truth as we find it and the right as we see it. We are der, then why doesn't he want to criminalize dedicated to the whole truth, to human values above all interests, to the rights of human-kind as the foundation it? How come abortion has never been prose- of democracy: we will take orders from none but our own cuted under murder laws? It would seem the conscience, and never will we overlook or misrepresent anti-aborts don't really take their propaganda the truth to serve the interests of the powerfid or cater seriously. Patricia Lunneborg's new work, Inside Information to the ignoble in the human spirit. Writers are responsible for their own work, but not Abortion, A Positive Decision (Greenwood, In her review of Who Will Tell The People, for anything they have not themselves written, and in pub- 1992), makes the point that the best reason (TO 8/21/92) Molly Ivins says "well upwards lishing them we do not necessarily imply that we agree to have an abortion is the desire not to bear of 60 percent of the cost of health care in this with them, because this is a journal of free voices.