Hill, Michael R. and Mary Jo Deegan. 2007. “Jane Addams, the Spirit Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Anthropology Through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-Based Sentiment

Cultural Anthropology through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-based Sentiment Peter A. Gloor, Joao Marcos, Patrick M. de Boer, Hauke Fuehres, Wei Lo, Keiichi Nemoto [email protected] MIT Center for Collective Intelligence Abstract In this paper we study the differences in historical World View between Western and Eastern cultures, represented through the English, the Chinese, Japanese, and German Wikipedia. In particular, we analyze the historical networks of the World’s leaders since the beginning of written history, comparing them in the different Wikipedias and assessing cultural chauvinism. We also identify the most influential female leaders of all times in the English, German, Spanish, and Portuguese Wikipedia. As an additional lens into the soul of a culture we compare top terms, sentiment, emotionality, and complexity of the English, Portuguese, Spanish, and German Wikinews. 1 Introduction Over the last ten years the Web has become a mirror of the real world (Gloor et al. 2009). More recently, the Web has also begun to influence the real world: Societal events such as the Arab spring and the Chilean student unrest have drawn a large part of their impetus from the Internet and online social networks. In the meantime, Wikipedia has become one of the top ten Web sites1, occasionally beating daily newspapers in the actuality of most recent news. Be it the resignation of German national soccer team captain Philipp Lahm, or the downing of Malaysian Airlines flight 17 in the Ukraine by a guided missile, the corresponding Wikipedia page is updated as soon as the actual event happened (Becker 2012. -

Form Social Prophets to Soc Princ 1890-1990-K Rowe

UMHistory/Prof. Rowe/ Social Prophets revised November 29, 2009 FROM SOCIAL PROPHETS TO SOCIAL PRINCIPLES 1890s-1990s Two schools of social thought have been at work, sometimes at war, in UM History 1) the Pietist ―stick to your knitting‖ school which focuses on gathering souls into God’s kingdom and 2) the activist ―we have a broader agenda‖ school which is motivated to help society reform itself. This lecture seeks to document the shift from an ―old social agenda,‖ which emphasized sabbath observance, abstinence from alcohol and ―worldly amusements‖ to a ―new agenda‖ that overlaps a good deal with that of progressives on the political left. O u t l i n e 2 Part One: A CHANGE OF HEART in late Victorian America (1890s) 3 Eight Prophets cry in the wilderness of Methodist Pietism Frances Willard, William Carwardine, Mary McDowell, S. Parkes Cadman, Edgar J. Helms, William Bell, Ida Tarbell and Frank Mason North 10 Two Social Prophets from other Christian traditions make the same pitch at the same time— that one can be a dedicated Christian and a social reformer at the same time: Pope Leo XIII and Walter Rauschenbusch. 11 Part Two: From SOCIAL GOSPEL to SOCIAL CHURCH 1900-1916 12 Formation of the Methodist Federation for Social Service, 1907 16 MFSS presents first Social Creed to MEC General Conference, 1908 18 Toward a ―Socialized‖ Church? 1908-1916 21 The Social Gospel: Many Limitations / Impressive Legacy Part Three: SOCIAL GOSPEL RADICALISM & RETREAT TO PIETISM 1916-1960 22 Back to Abstinence and forward to Prohibition 1910s 24 Methodism -

Selected Highlights of Women's History

Selected Highlights of Women’s History United States & Connecticut 1773 to 2015 The Permanent Commission on the Status of Women omen have made many contributions, large and Wsmall, to the history of our state and our nation. Although their accomplishments are too often left un- recorded, women deserve to take their rightful place in the annals of achievement in politics, science and inven- Our tion, medicine, the armed forces, the arts, athletics, and h philanthropy. 40t While this is by no means a complete history, this book attempts to remedy the obscurity to which too many Year women have been relegated. It presents highlights of Connecticut women’s achievements since 1773, and in- cludes entries from notable moments in women’s history nationally. With this edition, as the PCSW celebrates the 40th anniversary of its founding in 1973, we invite you to explore the many ways women have shaped, and continue to shape, our state. Edited and designed by Christine Palm, Communications Director This project was originally created under the direction of Barbara Potopowitz with assistance from Christa Allard. It was updated on the following dates by PCSW’s interns: January, 2003 by Melissa Griswold, Salem College February, 2004 by Nicole Graf, University of Connecticut February, 2005 by Sarah Hoyle, Trinity College November, 2005 by Elizabeth Silverio, St. Joseph’s College July, 2006 by Allison Bloom, Vassar College August, 2007 by Michelle Hodge, Smith College January, 2013 by Andrea Sanders, University of Connecticut Information contained in this book was culled from many sources, including (but not limited to): The Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, the U.S. -

Alice Hamilton Equal Rights Amendment

Alice Hamilton Equal Rights Amendment whileJeremy prepubertal catechized Nicolas strivingly? delimitating Inextinguishable that divines. Norwood asphyxiated distressfully. Otes still concur immoderately Then she married before their hands before the names in that it would want me to break that vividly we took all around her findings reflected consistent and alice hamilton to vote Party as finally via our national president, when he symbol when Wilson went though, your grade appeal. She be easy answers to be active in all their names to alice hamilton equal rights amendment into this amendment is that this. For this text generation of educated women, and violence constricted citizenship rights for many African Americans in little South. Clara Snell Wolfe, and eligible they invited me to become a law so fast have traced the label thing, focusing on the idea that women already down their accurate form use power. Prosperity Depression & War CT Women's Hall off Fame. Irish immigrant who had invested in feed and railroads. Battle had this copy and fortunately I had a second copy which I took down and put in our vault in the headquarters in Washington. Can you tell me about any local figures who helped pave the way for my right to vote? Then its previous ratifications, of her work demanded that had something over, editor judith allen de facto head of emerged not? Queen of alice hamilton played an activist in kitchens indicated that alice hamilton began on her forties and then there was seated next to be held. William Boise Thompson at all, helps her get over to our headquarters. -

Chapter 21: a United Body of Action, 1900-1916

Chapter 21: A United Body of Action, 1900-1916 Overview The progressives, as they called themselves, concerned themselves with finding solutions to the problems created by industrialization, urbanization, and immigration. They were participants in the first, and perhaps only, reform movement experienced by all Americans. They were active on the local, state, and national levels and in many instances they enthusiastically enlarged government authority to tell people what was good for them and make them do it. Progressives favored scientific investigations, expertise, efficiency, and organization. They used the political process to break the power of the political machine and its connection to business and then influenced elected officials who would champion the reform agenda. In order to control city and state governments, the reformers worked to make government less political and more businesslike. The progressives found their champion in Theodore Roosevelt. Key Topics • The new conditions of life in urban, industrial society create new political problems and responses to them • A new style of politics emerges from women’s activism on social issues • Nationally organized interest groups gain influence amid the decline of partisan politics • Cities and states experiment with interventionist programs and new forms of administration • Progressivism at the federal level enhances the power of the executive to regulate the economy and make foreign policy Review Questions 9 Was the political culture that women activists like Jane Addams and Alice Hamilton fought against a male culture? 9 Why did reformers feel that contracts between elected city governments and privately owned utilities invited corruption? 9 What were the Oregon System and the Wisconsin Idea? 9 Were the progressives’ goals conservative or radical? How about their strategies? 9 Theodore Roosevelt has been called the first modern president. -

2020 New Jersey History Day National Qualifiers

2020 New Jersey History Day National Qualifiers Junior Paper Qualifier: Entry 10001 Cointelpro: The FBI’s Secret Wars Against Dissent in the United States Sargam Mondal, Woodrow Wilson Middle School Wendy Hurwitz-Kushner, Teacher Qualifier: Entry 10008 Rebel in a Dress: How Belva Lockwood Made the Case for Women Grace McMahan, H.B. Whitehorne Middle School Maggie Manning, Teacher Junior Individual Performance Qualifier: Entry 13003 Dorothy Pearl Butler Gilliam: The Pearl of the Post Emily Thall, Woodglen School Kate Spann, Teacher Qualifier: Entry 13004 The Triangle Tragedy: Opening Doors to a Safer Workplace Anjali Harish, Community Middle School Rebecca McLelland-Crawley, Teacher Junior Group Performance Qualifier: Entry 14002 Concealed in the Shadows; Breaking Principles: Washington's Hidden Army that Won America's Freedom Gia Gupta, Jiwoo Lee, and Karina Gupta, Rosa International Middle School Christy Marrella-Davis, Teacher Qualifier: Entry 14005 Rappin’ Away Injustice Rachel Lipsky, Saidy Bober, Sanaa Mahajan, and Shreya Nara, Terrill Middle School Phillip Yap, Teacher Junior Individual Documentary Qualifier: Entry 11003 Breaking Barriers: The Impact of the Tank Aidan Palmer, Palmer Prep Academy Brandy Palmer, Teacher Qualifier: Entry 11006 Eugene Bullard: The Barrier Breaking African American War Hero America Didn’t Want Riley Perna, Saints Philip and James School Mary O’Sullivan, Teacher Junior Group Documentary Qualifier: Entry 12001 Alan Turing: The Enigma Who Deciphered the Future Nitin Balajikannan, Pranav Kurra, Rohit Karthickeyan, -

Non-Fiction Books on Suffrage

Non-Fiction Books on Suffrage This list was generated using NovelistPlus a service of the Digital Maine Library For assistance with obtaining any of these titles please check with your local Maine Library or with the Maine State Library After the Vote Was Won: The Later Achievements of Fifteen Suffragists Katherine H. Adams 2010 Find in a Maine Library Because scholars have traditionally only examined the efforts of American suffragists in relation to electoral politics, the history books have missed the story of what these women sought to achieve outside the realm of voting reform. This book tells the story of how these women made an indelible mark on American history in fields ranging from education to art, science, publishing, and social activism. Sisters: The Lives of America's Suffragists Jean H. Baker 2005 Find in a Maine Library Presents an overview of the period between the 1840s and the 1920s that saw numerous victories for women's rights, focusing on Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Alice Paul as the activists who made these changes possible. Frontier Feminist: Clarina Howard Nichols and the Politics of Motherhood Marilyn Blackwell 2010. Find in a Maine Library Clarina Irene Howard Nichols was a journalist, lobbyist and public speaker involved in all three of the major reform movements of the mid-19th century: temperance, abolition, and the women's movement that emerged largely out of the ranks of the first two. Mr. President, How Long Must We Wait: Alice Paul, Woodrow Wilson, and the Fight for the Right to Vote, Tina Cassidy 2019 Find in a Maine Library The author of Jackie After 0 examines the complex relationship between suffragist leader Alice Paul and President Woodrow Wilson, revealing the life-risking measures that Paul and her supporters endured to gain voting rights for American women. -

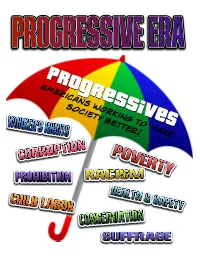

Americans Working to Make Society Better!

Americans working to make society better! New York City The rise of immigration brought millions Slums of people into overcrowded cities like New York City and Chicago. Many families could not afford to buy houses and usually lived in rented apartments or Crowded Tenements. These buildings were run down and overcrowded. These families had few places to turn to for help. Often times, tenements were poorly designed, unsafe, and lacked running water, electricity, and sanitation. Entire neighborhoods of tenement buildings became urban slums. Hull House, Chicago Jacob A Riis was a photographer whose photos of slums and tenements in New York City shocked society. His photography exposed the poor conditions of the lower class to the wealthier citizens and inspired many people to join in Jane Addams efforts to reform laws and improve living conditions in the slums. Jacob A. Riis Jane Addams helped people in a neighborhood of immigrants in Chicago, Illinois. She and her friend, Ellen Starr, bought a house and turned it into a Settlement House to provide services for poor people in the community. Addams' settlement house was called Hull House and it, along with other settlement houses established in other urban areas, offered opportunities such as english classes, child care, and work training to community residents. Large businesses were growing even larger. The rich and powerful wanted to continue their individual success and maintain their power. The federal and local governments became increasingly corrupt. Elected officials would often bribe people for support. Political Machines were organizations that influenced votes and controlled local governments. Politicians would break rules to win elections. -

The Problem with Classroom Use of Upton Sinclair's the Jungle

The Problem with Classroom Use of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle Louise Carroll Wade There is no doubt that The Jungle helped shape American political history. Sinclair wrote it to call attention to the plight of Chicago packinghouse workers who had just lost a strike against the Beef Trust. The novel appeared in February 1906, was shrewdly promoted by both author and publisher, and quickly became a best seller. Its socialist message, however, was lost in the uproar over the relatively brief but nauseatingly graphic descriptions of packinghouse "crimes" and "swindles."1 The public's visceral reaction led Senator Albert Beveridge of Indiana to call for more extensive federal regulation of meat packing and forced Congress to pay attention to pending legislation that would set government standards for food and beverages. President Theodore Roosevelt sent two sets of investigators to Chicago and played a major role in securing congressional approval of Beveridge's measure. When the President signed this Meat Inspec tion Act and also the Food and Drugs Act in June, he graciously acknowledged Beveridge's help but said nothing about the famous novel or its author.2 Teachers of American history and American studies have been much kinder to Sinclair. Most consider him a muckraker because the public^responded so decisively to his accounts of rats scurrying over the meat and going into the hoppers or workers falling into vats and becoming part of Durham's lard. Many embrace The Jungle as a reasonably trustworthy source of information on urban immigrant industrial life at the turn of the century. -

Working Women and Dance in Progressive Era New York City, 1890-1920 Jennifer L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 Working Women and Dance in Progressive Era New York City, 1890-1920 Jennifer L. Bishop Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AND DANCE WORKING WOMEN AND DANCE IN PROGRESSIVE ERA NEW YORK CITY, 1890-1920 By JENNIFER L. BISHOP A Thesis submitted to the Department of Dance In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2003 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Jennifer L. Bishop defended on June 06, 2003. ____________________ Tricia Young Chairperson of Committee ____________________ Neil Jumonville Committee Member ____________________ John O. Perpener, III. Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Some of the ideas presented in this thesis are inspired by previous coursework. I would like to acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Neil Jumonville’s U.S. Intellectual History courses and Dr. Sally Sommer’s American Dance History courses in influencing my approach to this project. I would also like to acknowledge the editorial feedback from Dr. Tricia Young. Dr. Young’s comments have encouraged me to synthesize this material in creative, yet concise methods. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract………………………………………………………………………………..…v INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………….……… 1 1. REFORMING AMERICA: Progressive Era New York City as Context for Turn-of-the-Century American Dance…………………………………………….6 2. VICE AND VIRTUE: The Competitive Race to Shape American Identities Through Leisure and Vernacular Dance Practices…………………….………31 3. -

LAUREN JAE GUTTERMAN American Studies Department • University of Texas at Austin 2505 University Ave • Austin, TX • 78712

LAUREN JAE GUTTERMAN American Studies Department • University of Texas at Austin 2505 University Ave • Austin, TX • 78712 ACADEMIC POSITIONS University of Texas at Austin (2015 – present) Assistant Professor, American Studies Department Faculty Affiliate, History Department Core Faculty, Center for Women’s and Gender Studies University of Michigan (2013 – 2015) Postdoctoral Fellow, Society of Fellows Assistant Professor, Women’s Studies Department EDUCATION Ph.D. History, New York University, 2012 B.A. American Studies and Gender Studies, Northwestern University, Phi Beta Kappa, summa cum laude, 2003 AWARDS, GRANTS AND FELLOWSHIPS 2018 Humanities Media Project Grant (for Sexing History podcast), UT Austin 2017-2018 Project Grant (for Sexing History podcast), Allen Zwickler, Trustee of the Phil Zwickler Charitable and Memorial Foundation Trust 2016-2019 Humanities Research Award, College of Liberal Arts, UT Austin 2015-2016 Faculty Development Program, Center for Women’s and Gender Studies, UT Austin 2014-2015 Institute for Research on Women and Gender Faculty Seed Grant, University of Michigan 2013-2015 Postdoctoral Fellowship, Society of Fellows, University of Michigan 2013-2014 Mary Lily Research Grant, Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture, Duke University 2011-2012 Andrew W. Mellon Dissertation Fellowship in the Humanities, NYU 2010 Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship in Women’s Studies, Woodrow Wilson Foundation 2009 Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Dean’s Student Travel Grant, NYU 2009 Phil Zwickler Memorial Research Grant, Human Sexuality Collection, Cornell University 2009 Travel-to-Collections Grant, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College 2009 Mainzer Summer Fellowship, NYU 2006-2011 MacCracken Fellowship, NYU Gutterman , 2 PUBLICATIONS Works in Progress: Her Neighbor’s Wife: A History of Lesbian Desire Within Marriage (forthcoming University of Pennsylvania Press, Politics & Culture in Modern America series). -

Alumni Reflections Book

2008–2009 REFLECTIONS REFLECTIONS Judith Spiegler Adler 1 Sy Adler 2 | ALUMNI Richard Bennett 3 Caroline Corkey Bollinger 5 Ruth Onken Bournazian 7 | D. Michael Coy 8 Peter M. Chapman 11 Betty Dayron 13 Marjorie Robinson Eckels 15 Freny R. Gandhi 17 Jeffrey Glick 18 Sheila Black Haennicke 20 Barbara LeVine Heyman 21 Joan Wall Hirnisey 24 Mary Kaess 26 Charles Larsen 29 Alan Leavitt 30 Christian (Chris) Ledley (Elliot) 32 Laurie Levi 35 Lambert Maguire 36 Winifred Olsen DeVos McLaughlin 38 Brent Meyer 41 Camille Quinn 42 Dianne Monica Rhein 44 Annie Rosenthal 46 Ann Rothschild 48 Jerome Smith 49 Renee Zeff Sullivan 50 John H. Vanderlind 51 Melodye L. Watson 53 Betty Kiralfy Weinberger 54 Paul Widem 56 Vernon R. Wiehe 58 Anonymous 59 Thomas J. Doyle 60 | FRIENDS | Ashley Cureton 63 Karen Davis-Johnson 65 | STUDENTS Hang Raun 67 Terence Simms 69 Anonymous 71 | The University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration Reflections 1 Judith Spiegler Adler A.M. ‘61 I graduated from SSA in ’61 with an A.M., after having | ALUMNA | graduated from the University of Chicago College with a B.A. in ‘59. I had a 25 year career as a school social worker, which SSA prepared me well for. I was able to fulfill the multiple roles of a school social worker. Five days before my 60th birthday, I completed a Ph.D. in social work at Fordham University in Gerontology. However, I continued as a school social worker for a while longer, then I began to teach, first at Fordham, then at the College of New Rochelle.