Columbia Poetry Review Publications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

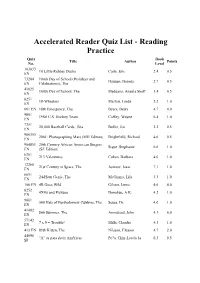

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 103833 10 Little Rubber Ducks Carle, Eric 2.4 0.5 EN 73204 100th Day of School (Holidays and Haugen, Brenda 2.7 0.5 EN Celebrations), The 41025 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 EN 8251 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda 5.2 1.0 EN 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 9801 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Coffey, Wayne 6.4 1.0 EN 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards...Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 EN 900355 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Edition) Brightfield, Richard 4.6 0.5 EN 904851 20th Century African American Singers Sigue, Stephanie 6.6 1.0 EN (SF Edition) 6201 213 Valentines Cohen, Barbara 4.0 1.0 EN 12260 21st Century in Space, The Asimov, Isaac 7.1 1.0 EN 6651 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila 3.3 1.0 EN 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8252 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. 4.2 1.0 EN 9001 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 EN 41482 $66 Summer, The Armistead, John 4.3 6.0 EN 57142 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 4.3 1.0 EN 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 44096 "A" es para decir Am?ricas Pe?a, Chin-Lee/de la 6.3 0.5 SP Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. -

A ADVENTURE C COMEDY Z CRIME O DOCUMENTARY D DRAMA E

MOVIES A TO Z MARCH 2021 Ho u The 39 Steps (1935) 3/5 c Blondie of the Follies (1932) 3/2 Czechoslovakia on Parade (1938) 3/27 a ADVENTURE u 6,000 Enemies (1939) 3/5 u Blood Simple (1984) 3/19 z Bonnie and Clyde (1967) 3/30, 3/31 –––––––––––––––––––––– D ––––––––––––––––––––––– –––––––––––––––––––––– ––––––––––––––––––––––– c COMEDY A D Born to Love (1931) 3/16 m Dancing Lady (1933) 3/23 a Adventure (1945) 3/4 D Bottles (1936) 3/13 D Dancing Sweeties (1930) 3/24 z CRIME a The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1960) 3/23 P c The Bowery Boys Meet the Monsters (1954) 3/26 m The Daughter of Rosie O’Grady (1950) 3/17 a The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) 3/9 c Boy Meets Girl (1938) 3/4 w The Dawn Patrol (1938) 3/1 o DOCUMENTARY R The Age of Consent (1932) 3/10 h Brainstorm (1983) 3/30 P D Death’s Fireworks (1935) 3/20 D All Fall Down (1962) 3/30 c Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) 3/18 m The Desert Song (1943) 3/3 D DRAMA D Anatomy of a Murder (1959) 3/20 e The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) 3/27 R Devotion (1946) 3/9 m Anchors Aweigh (1945) 3/9 P R Brief Encounter (1945) 3/25 D Diary of a Country Priest (1951) 3/14 e EPIC D Andy Hardy Comes Home (1958) 3/3 P Hc Bring on the Girls (1937) 3/6 e Doctor Zhivago (1965) 3/18 c Andy Hardy Gets Spring Fever (1939) 3/20 m Broadway to Hollywood (1933) 3/24 D Doom’s Brink (1935) 3/6 HORROR/SCIENCE-FICTION R The Angel Wore Red (1960) 3/21 z Brute Force (1947) 3/5 D Downstairs (1932) 3/6 D Anna Christie (1930) 3/29 z Bugsy Malone (1976) 3/23 P u The Dragon Murder Case (1934) 3/13 m MUSICAL c April In Paris -

110% Gaming 220 Triathlon Magazine 3D World Adviser

110% Gaming 220 Triathlon Magazine 3D World Adviser Evolution Air Gunner Airgun World Android Advisor Angling Times (UK) Argyllshire Advertiser Asian Art Newspaper Auto Car (UK) Auto Express Aviation Classics BBC Good Food BBC History Magazine BBC Wildlife Magazine BIKE (UK) Belfast Telegraph Berkshire Life Bikes Etc Bird Watching (UK) Blackpool Gazette Bloomberg Businessweek (Europe) Buckinghamshire Life Business Traveller CAR (UK) Campbeltown Courier Canal Boat Car Mechanics (UK) Cardmaking and Papercraft Cheshire Life China Daily European Weekly Classic Bike (UK) Classic Car Weekly (UK) Classic Cars (UK) Classic Dirtbike Classic Ford Classic Motorcycle Mechanics Classic Racer Classic Trial Classics Monthly Closer (UK) Comic Heroes Commando Commando Commando Commando Computer Active (UK) Computer Arts Computer Arts Collection Computer Music Computer Shopper Cornwall Life Corporate Adviser Cotswold Life Country Smallholding Country Walking Magazine (UK) Countryfile Magazine Craftseller Crime Scene Cross Stitch Card Shop Cross Stitch Collection Cross Stitch Crazy Cross Stitch Gold Cross Stitcher Custom PC Cycling Plus Cyclist Daily Express Daily Mail Daily Star Daily Star Sunday Dennis the Menace & Gnasher's Epic Magazine Derbyshire Life Devon Life Digital Camera World Digital Photo (UK) Digital SLR Photography Diva (UK) Doctor Who Adventures Dorset EADT Suffolk EDGE EDP Norfolk Easy Cook Edinburgh Evening News Education in Brazil Empire (UK) Employee -

B E N N I N G T O N W R I T I N G S E M I N A

MFAW PUBLIC SCHEDULE June 15–24, 2017 NOTE: Schedule subject to change All faculty, guest, and graduate lectures and readings will be held in Tishman Lecture Hall, unless otherwise indicated. All evening Faculty and Guest Readings will be held in the Deane Carriage Barn. Thursday, June 15 7:00 Faculty & Guest Readings: Kaitlyn Greenidge and Amy Hempel Friday, June 16 Graduate Readings 4:00 Alexander Benaim 4:20 Andrea Caswell 4:40 Michael Connor 7:00 Faculty & Guest Readings: Benjamin Anastas and Mark Wunderlich 8:00 Historical Presentation: Lynne Sharon Schwartz: “Historic Recordings of Great 20th Century American Authors Reading their Work.” Deane Carriage Barn Saturday, June 17 Graduate Lectures 8:20 Ashley Olsen: “50 Shades of Consent: Sexual Desire and Sexual Violence in Contemporary Short Stories.” This lecture will examine tests from contemporary female authors including Mary Gaitskill, Margaret Atwood, and Roxane Gay. 9:00 Katie Pryor: “Persona & Violence in Ai’s Cruelty & Iliana Rocha’s Karankawa.” Both of these poets use persona poems to explore violence. What is powerful about this poetic device? How does the persona poem involve the reader and interrogate our notions of self? We’ll explore the connections and differences between these poets and their first books. 9:40 Karen Rile: “The Bad Writing Competition: Introducing Narrative Distance to Undergraduates.” A technique-centered workshop that offers coordinated readings and prompts can help beginning writers focus on discrete, achievable goals. But demonstrating smooth narrative distance shifts presents a practical challenge in an undergraduate workshop setting. The Bad Writing Competition, or mastery through parody, is a deft solution—with some unexpected ancillary benefits. -

![COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/complete-music-list-by-artist-no-of-tunes-6773-465125.webp)

COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]

[ COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ] 001 PRODUCTIONS >> BIG BROTHER THEME 10CC >> ART FOR ART SAKE 10CC >> DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 10CC >> GOOD MORNING JUDGE 10CC >> I'M NOT IN LOVE {K} 10CC >> LIFE IS A MINESTRONE 10CC >> RUBBER BULLETS {K} 10CC >> THE DEAN AND I 10CC >> THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 >> DANCE WITH ME 1200 TECHNIQUES >> KARMA 1910 FRUITGUM CO >> SIMPLE SIMON SAYS {K} 1927 >> IF I COULD {K} 1927 >> TELL ME A STORY 1927 >> THAT'S WHEN I THINK OF YOU 24KGOLDN >> CITY OF ANGELS 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 2PAC >> THUGS MANSION 3 DOORS DOWN >> BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> LOSER 3 L W >> NO MORE ( BABY I'M A DO RIGHT ) 30 SECONDS TO MARS >> CLOSER TO THE EDGE 360 >> LIVE IT UP 360 >> PRICE OF FAME 360 >> RUN ALONE 360 FEAT GOSSLING >> BOYS LIKE YOU 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY >> STARSTRUKK 3OH!3 FEAT KESHA >> MY FIRST KISS 4 THE CAUSE >> AIN'T NO SUNSHINE 4 THE CAUSE >> STAND BY ME {K} 4PM >> SUKIYAKI 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> DON'T STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> GIRLS TALK BOYS {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> LIE TO ME {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> TEETH 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> YOUNGBLOOD {K} 50 CENT >> 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT >> AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT >> CANDY SHOP 50 CENT >> IF I CAN'T 50 CENT >> IN DA CLUB 50 CENT >> P I M P 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA 5000 VOLTS >> I'M ON FIRE 5TH DIMENSION -

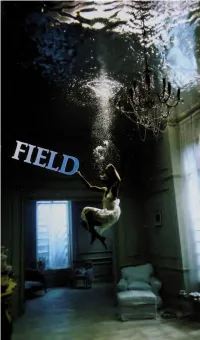

FIELD, Issue 93, Fall 2015

FIELD CONTEMPORARY POETRY AND POETICS NUMBER 93 FALL 2015 OBERLIN COLLEGE PRESS EDITORS David Young David Walker ASSOCIATE Pamela Alexander EDITORS Kazim Ali DeSales Harrison Shane McCrae EDITOR-AT- Martha Collins LARGE MANAGING Marco Wilkinson EDITOR EDITORIAL Paris Gravley ASSISTANT DESIGN Steve Farkas www.oberlin.edu/ocpress Published twice yearly by Oberlin College. Poems should be submitted through the online submissions manager on our website. Subscription orders should be sent to FIELD, Oberlin College Press, 50 N. Professor St., Oberlin, OH 44074. Checks payable to Oberlin College Press: $16.00 a year / $28.00 for two years / $40.00 for 3 years. Single issues $8.00 postpaid. Please add $4.00 per year for Canadian addresses and $9.00 for all other countries. Back issues $12.00 each. Contact us about availability. FIELD is also available for download from the Os&ls e-bookstore. See www.0s-ls.com/field. FIELD is indexed in Humanities International Complete. Copyright © 2015 by Oberlin College. ISSN: 0015-0657 CONTENTS 7 Russell Edson: A Symposium John Gallaher 11 So Are We to Laugh or What Dennis Schmitz 15 Edson's Animals Lee Upton 20 Counting Russell Edson Charles Simic 23 Easy as Pie B. K. Fischer 26 Some Strange Conjunction Jon Loomis 31 Consider the Ostrich * * Elizabeth Gold 35 A Child's Guide to the Icebergs 36 Dementia Cait Weiss 37 Calabasas 38 The Prophets Mark Irwin 39 Events miniaturized, but always present G. C. Waldrep 40 Lyme Vector (I) Cynthia Cruz 41 Guidebooks for the Dead (I) 42 Guidebooks for the Dead (II) Ales Steger 43 The Ancient Roman Walls translated by Brian Henry and Urska Charney Hailey Leithauser 44 Slow Danger 45 Midnight Catherine Bull 46 Muskoxen 47 Long Day Karl Krolow 48 A Sentence translated by Stuart Friebert 49 We're Living Faster Tam B lax ter 50 Stillness in the passenger seat after the impact 51 Having left by the back door 52 Back Mary Ann Samyn 53 Things Nozv Remind Us of Things Then 54 Understanding and Doing 55 Better Already (3) Beverley Bie Brahic 56 Black Box fames Hang 57 [First it didn't sound...] D. -

Facing the Future in Migration's Past

Double Time: Facing The Future in Migration’s Past Derek Duncan By picturing our wishes as fulfilled, dreams are after all leading us into the future. But this future, which the dreamer pictures as the present, has been moulded by his indestructible wish into a perfect likeness of the past. --Sigmund Freud, Interpretation of Dreams Trauma is not necessarily a single event, but a series of events that affects the imaginary and the symbolic. --Maureen Turim, Flashbacks in Film In La mia casa è dove sono, Igiaba Scego explores the imaginary and real geographies of memory and belonging as she maps the contours of her identity as an Italian woman of Somali origin. Scego paints a vivid picture of her native city’s new materiality: “Una Roma dove la globalizzazione si è fatta carne” (2010, 157). She recounts the astonishment of her brother on his first visit from England when he sees a group of Italian boys playing cricket with some Sri Lankan friends. Scego is quite happy with the new diversity reflecting that “[l]e mazze di cricket e i sari non sono altro che i segni di un futuro che non solo verrà, ma che è già qui da discreto tempo” (157). In the gendered symbolism of the cricket bats and the saris, Scego foresees a multicultural future that has already become past. In a gesture that is characteristic of many attempts to envisage what the nation will become, she then immediately returns to more distant times: “Qui ci sono passati tutti, arabi, normanni, francesi, austriaci. C’è passato Annibale, condottiero africano, con i suoi elefanti” (157-58), a historical fact, she reminds the reader, recalled relatively recently by the Neapolitan hip-hop band Almamegretta. -

Catholic-Courier-Journal-1961

y ! 5 *-"?£mA;!*n v^^M^ffiSiSp * * \prm-&*TfpFH!!p ^jft^fpl&faainKii^fc^E^irjJa^fttL isfmeMffi&in?' • W COURIER-JOURNAL 'Diary Of Anne Frank' Theatre Guide Watching The Screen Friday, February 3,1961 11 RIVIERA Ben-Hur A-l Listed At Merqrmgti (Unobjectionable) Observation—The Legion of De cency recommends Ben-Hur Names Not The Same as wholesome entertainment on an unusually high level of By RAY SMITH sake, let's look at some of our by a gent named William Shake* stars. annual school achievement for the whole Looking at the marquee .we speare. (I wonder if that was lay at Mercy. wMi he directed family. see now and then some exotic his real name.) To this inquiry RECENTLY WE saw her as we may not always recall Im y Sister Mary Pius. fore they were discovered. Aii1| sweet • sounding name and one of the leads in "Midnight >E account of those year*-was kept;j|| HIAL.T0—East Bochester wonder why the parents ever mediately the -correct answer, Lace." Her parents knew her but the question still remains, The play is the story of a by Anne, a young teenage girL^f 3 Worlds of Gulliver A-l hung such a handle on their German Jewish family who as Doris Kappelhoff but we will an intriguing one. 10 The play was dramatized by Han On a String A-l child. But we can't always or remember her as Doris Day, A •ought refuge from Hitler in ^ Midnight Lace A-2 ever blame the parents. More few ihoons ago The Grass "was" Holland and hid for 2^ • years!*rances Goodrich and Albert ,S (Unobjectionable for adults often it is that little commun Greener at the Palace Theatre in an attic above a factory be- Hackett from the bestseller,, ity called Hollywood that BROADEN and adolescents) and Archibald Alexander Leach Anne Frank: Diary of "a Young : changes the name. -

Stephen-King-Book-List

BOOK NERD ALERT: STEPHEN KING ULTIMATE BOOK SELECTIONS *Short stories and poems on separate pages Stand-Alone Novels Carrie Salem’s Lot Night Shift The Stand The Dead Zone Firestarter Cujo The Plant Christine Pet Sematary Cycle of the Werewolf The Eyes Of The Dragon The Plant It The Eyes of the Dragon Misery The Tommyknockers The Dark Half Dolan’s Cadillac Needful Things Gerald’s Game Dolores Claiborne Insomnia Rose Madder Umney’s Last Case Desperation Bag of Bones The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon The New Lieutenant’s Rap Blood and Smoke Dreamcatcher From a Buick 8 The Colorado Kid Cell Lisey’s Story Duma Key www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Just After Sunset The Little Sisters of Eluria Under the Dome Blockade Billy 11/22/63 Joyland The Dark Man Revival Sleeping Beauties w/ Owen King The Outsider Flight or Fright Elevation The Institute Later Written by his penname Richard Bachman: Rage The Long Walk Blaze The Regulators Thinner The Running Man Roadwork Shining Books: The Shining Doctor Sleep Green Mile The Two Dead Girls The Mouse on the Mile Coffey’s Heads The Bad Death of Eduard Delacroix Night Journey Coffey on the Mile The Dark Tower Books The Gunslinger The Drawing of the Three The Waste Lands Wizard and Glass www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Wolves and the Calla Song of Susannah The Dark Tower The Wind Through the Keyhole Talisman Books The Talisman Black House Bill Hodges Trilogy Mr. Mercedes Finders Keepers End of Watch Short -

Private Sector

The Memory Keeper's Daughter Kim Edwards PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R oRL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen's Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi — 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R oRL, England First published in the United States of America by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. 2005 Published in Penguin Books 2006 11 13 15 17 19 20 18 16 14 12 Copyright © Kim Edwards, 2005 All rights reserved publisher's note This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. ISBNo 14 30.3714 5 CIP data available Printed in the United States of America Designed by Carlo. Bolte • Set in Granjon Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

5Th Grade Newspaper 5Th Grade New Is a Group of Five 5Th Graders That Falcon Harold News Come Together and Write for the Whole School Sunday, March 7 Week 3

5th Grade Newspaper 5th Grade New is a group of five 5th Graders that Falcon Harold News come together and write for the whole school Sunday, March 7 Week 3 Teacher Of The Year! Lunch and Breakfast By: Lauryn Jimenez BREAKFAST MONAD1 Y: Strawberry Nutrigrain Bar TUESDAY: Glazed Cinnamon Rolls WEDNSDAY: Annie's Honey Bunny Graham's THURSDAY: Omlet & Homestyle Biscut FRIDAY: Lucky Charms Cereal LUNCH MONDAY: Breaded Popcorn Chicken TUESDAY: Rotini Marinara w/ By: 5th Grade Newspaper Meatballs WEDNSDAY:Grilled Do you know who the teacher of the year is? Mrs. Hjelmstad, 5th grade's Cheeseburger THURSDAY:Pulled teacher. We are so proud of her. She truly deserves it! She was so surprised Chicken Savory that she won . Her kids came in with balloons, owers and a cupcake. How Nachos FRIDAY:Cheesy sweet! Congratulations Mrs. Hjelmstad we love you so much. <3 Two Cheese Pizza Zodiac Signs & DIY DIY Craft By: Nayeli Martinez Today you will be learning how to make a D.I.Y stress ball! WHAT YOU NEED 1.Balloon 2.For the inside you can use flour, rice, beads, or play dough. 3.Funnel for the flour For the stress ball you get your balloon and open the top to put what you have inside. (if you are using flour you should use a funnel) once you have the material inside, get the balloon, tie it up, and then you can start playing with it and enjoy! Have fun playing with your D.I.Y stress ball! Zodiac Sign By: Nayeli Martinez What is your month spirit animal? Aries- hawk Taurus- beaver Gemini- deer Cancer- woodpecker Leo- salmon Virgo- bear Libra- raven Caption Scorpio- snake At malesuada Sagittarius- owl nisl felis sit Capricorn- goose amet dolor Aquarius- otter Pisces- wolf (LOOK AT THE PHOTO ABOVE TO FIND YOUR ZODIAC SIGN) Women all over American Women's History Month have helped change the way women's rights today! Susan B.