Digital Content From: Irish Historic Towns Atlas (IHTA), No. 1, Kildare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mountmellick, Mountrath, Abbeyleix, Co. Laois, Monasterevin, Co

3. Group 2: Mountmellick, Mountrath, Abbeyleix, Co. Laois, and Monasterevin, Co. Kildare. 3.1. Mountmellick, Co. Laois 3.1.1. Summary Details: Mountmellick is located 11km from the regional hub town of Portlaoise. The population of Mountmellick is currently 2,872 as per the results of the 2006 Census. This is projected to increase to 4,540 by 2018 (see Appendix B). It is forecast that up to 500 houses will be connected in Mountmellick over the next ten years. The projected figure is based on housing completion figures, census population report, Laois housing strategy and Laois County Development Plan. The main employer in the town is St. Vincent’s Hospital. Another significant I/C load in the town is Standex Ireland Ltd. It is expected that with population growth at least a proportional increase in I/C customers will develop. Mountmellick is situated 7km from the existing Portarlington feeder main. 3.1.2. Summary Load Analysis: Mountmellick, Co. Laois. Source: Networks cost estimates report June 2007 Industrial/Commercial Load Summary Forecast: Total EAC 2014 6,639 MWh 226,600 Therms Peak Day 2014 37,958 kWh 1,295 Therms New Housing Summary Forecast: New Housing Load (Therm) 260,000 (year 10) New Housing Load (MWh) 7,620 (year 10) 3.1.3. Solutions: The most economic option for supplying Mountmellick town is by installing a 250mm PE100 SDR17 feeder main from Portlaoise (6.8 km approx). A reinforcement of the Portlaoise network is also required as a result of the connection of Mountmellick to this network, the costs of which have been included in the analysis. -

1 Liturgical Year 2020 of the Celtic Orthodox Church Wednesday 1St

Liturgical Year 2020 of the Celtic Orthodox Church Wednesday 1st January 2020 Holy Name of Jesus Circumcision of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ Basil the Great, Bishop of Caesarea of Palestine, Father of the Church (379) Beoc of Lough Derg, Donegal (5th or 6th c.) Connat, Abbess of St. Brigid’s convent at Kildare, Ireland (590) Ossene of Clonmore, Ireland (6th c.) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 3:10-19 Eph 3:1-7 Lk 6:5-11 Holy Name of Jesus: ♦ Vespers: Ps 8 and 19 ♦ 1st Nocturn: Ps 64 1Tm 2:1-6 Lk 6:16-22 ♦ 3rd Nocturn: Ps 71 and 134 Phil 2:6-11 ♦ Matins: Jn 10:9-16 ♦ Liturgy: Gn 17:1-14 Ps 112 Col 2:8-12 Lk 2:20-21 ♦ Sext: Ps 53 ♦ None: Ps 148 1 Thursday 2 January 2020 Seraphim, priest-monk of Sarov (1833) Adalard, Abbot of Corbie, Founder of New Corbie (827) John of Kronstadt, priest and confessor (1908) Seiriol, Welsh monk and hermit at Anglesey, off the coast of north Wales (early 6th c.) Munchin, monk, Patron of Limerick, Ireland (7th c.) The thousand Lichfield Christians martyred during the reign of Diocletian (c. 333) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:1-6 Eph 3:8-13 Lk 8:24-36 Friday 3 January 2020 Genevieve, virgin, Patroness of Paris (502) Blimont, monk of Luxeuil, 3rd Abbot of Leuconay (673) Malachi, prophet (c. 515 BC) Finlugh, Abbot of Derry (6th c.) Fintan, Abbot and Patron Saint of Doon, Limerick, Ireland (6th c.) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:7-14a Eph 3:14-21 Lk 6:46-49 Saturday 4 January 2020 70 Disciples of Our Lord Jesus Christ Gregory, Bishop of Langres (540) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:14b-20 Eph 4:1-16 Lk 7:1-10 70 Disciples: Lk 10:1-5 2 Sunday 5 January 2020 (Forefeast of the Epiphany) Syncletica, hermit in Egypt (c. -

BROWN GELDING 1 (Branded Nr Sh

Barn D Stable 55 On Account of CHEVAL THOROUGHBREDS, Tooradin Lot 1 BROWN GELDING 1 (Branded nr sh. off sh. Foaled 15th October 2015) 5 Perugino (USA) ...............by Danzig ..................... Testa Rossa .................... SIRE Bo Dapper ................. by Sir Dapper .............. UNENCUMBERED ..... More Than Ready (USA) by Southern Halo ......... Blizzardly ....................... Concise ...................... by Marscay .................. Alannon ...................... by Noalcoholic (Fr) ........ DAM Falvelon .......................... Devil's Zephyr ............ by Zephyr Zing (NZ) .... QUEEN FALVELON ..... Leo Castelli ................ by Sovereign Dancer .... 2004 Queen Castelli (USA) ...... Queen Alexandra ........ by Determined King ..... UNENCUMBERED (AUS) (Bay or Brown 2011-Stud 2014). 5 wins at 2, A$1,908,850, BRC BJ McLachlan S., Gr.3, GCTC Magic Millions 2YO Classic, RL, Wyong Magic Millions 2YO Classic, RL, ATC Ascend Sale Trophies 2YO P., Sharp 2YO P., 2d ATC Todman S., Gr.2. Out of SW Blizzardly (AJC Keith Mackay H., L). Related to SW Rembetica (NSW Tatt's RC Tramway H., Gr.3) and SW Sober Dancer. His oldest progeny are 2YOs. 1st Dam QUEEN FALVELON, by Falvelon. 2 wins at 2 at 1113, 1200m, MRC Holmesglen 2YO H., 3d MRC Canonise 2YO H. This is her fifth foal. Her fourth foal is an unraced 3YO. Dam of 1 foal to race, 1 winner- Young Farrelly (g by Estambul (ARG)). 3 wins at 1008m. 2nd Dam Queen Castelli (USA), by Leo Castelli. 3 wins at 6f, 8¼f, 3d Meadowlands Bloomfield College S., L. Dam of 6 named foals, all raced, 4 winners- Gabrieli. Winner at 1000m, MRC Brava Jeannie H. Dam of 4 winners- Tariana (f Anabaa (USA)). 6 wins 1100 to 1209m, $287,220, MVRC LF Signs H., MRC Hayman Island H., Ken Sturt H., John Moule H., 2d TRC Bow Mistress Trophy, Gr 3, MRC Ricoh H., 3d TTC Vamos S., L. -

CNI News Mar 23

March 23, 2019 ! EU president’s praise for Catholic teaching welcomed A call from European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker for the EU to rediscover its Catholic roots is an invitation for politicians to bring Catholic values to bear in their work, Bishop Noel Treanor (above) of Down and Connor has said. [email protected] Page !1 March 23, 2019 Addressing the spring assembly of COMECE – the European bishops’ conference – Mr Juncker spoke effusively about the importance of Catholic social teaching, upon which the European project was founded in the aftermath of World War Two. “I am a fervent advocate of the social doctrine of the Church. It is one of the most noble teachings of our Church,” Mr Juncker said on March 14. “All of this is part of a doctrine that Europe does not apply often enough. I would like us to rediscover the values and guiding principles of the social teaching of the Church.” Speaking to The Irish Catholic, Bishop Treanor explained that Mr Juncker had been looking back on the achievements and challenges that have marked the European project over the last five years, looking ahead to the future. “He began by emphasising that this European project is inclusive, it doesn’t exclude anybody,” Dr Treanor said. “He quoted Pope John Paul II, saying it has two lungs – east and west – and went on to talk about the European Union being a peace-building project. “He emphasised the importance of that, mentioning that after some 60-70 years of European construction the permanent challenge of building, maintaining, and consolidating peace is something that escapes those who have not had the experience of war, and in terms of our relationships with our neighbours and in terms of internal tensions the importance of building true peace and security is foundational,” he said. -

The Rivers of Borris County Carlow from the Blackstairs to the Barrow

streamscapes | catchments The Rivers of Borris County Carlow From the Blackstairs to the Barrow A COMMUNITY PROJECT 2019 www.streamscapes.ie SAFETY FIRST!!! The ‘StreamScapes’ programme involves a hands-on survey of your local landscape and waterways...safety must always be the underlying concern. If WELCOME to THE DININ & you are undertaking aquatic survey, BORRIS COMMUNITY GROUP remember that all bodies of water are THE RIVERS potentially dangerous places. MOUNTAIN RIVERS... OF BORRIS, County CARLow As part of the Borris Rivers Project, we participated in a StreamScapes-led Field Trip along the Slippery stones and banks, broken glass Dinin River where we learned about the River’s Biodiversity, before returning to the Community and other rubbish, polluted water courses which may host disease, poisonous The key ambitions for Borris as set out by the community in the Borris Hall for further discussion on issues and initiatives in our Catchment, followed by a superb slide plants, barbed wire in riparian zones, fast - Our Vision report include ‘Keep it Special’ and to make it ‘A Good show from Fintan Ryan, and presentation on the Blackstairs Farming Futures Project from Owen moving currents, misjudging the depth of Place to Grow Up and Grow Old’. The Mountain and Dinin Rivers flow Carton. A big part of our engagement with the River involves hearing the stories of the past and water, cold temperatures...all of these are hazards to be minded! through Borris and into the River Barrow at Bún na hAbhann and the determining our vision and aspirations for the future. community recognises the importance of cherishing these local rivers If you and your group are planning a visit to a stream, river, canal, or lake for and the role they can play in achieving those ambitions. -

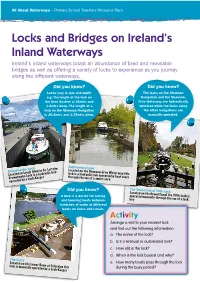

Locks and Bridges on Ireland's Inland Waterways an Abundance of Fixed

ack eachers Resource P ways – Primary School T All About Water Locks and Bridges on Ireland’s Inland Waterways Ireland’s inland waterways boast an abundance of fixed and moveable bridges as well as offering a variety of locks to experience as you journey along the different waterways. Did you know? Did you know? The locks on the Shannon Navigation and the Shannon- Locks vary in size and depth Erne Waterway are hydraulically e.g. the length of the lock on operated while the locks along the Erne System is 36mtrs and the other navigations are 1.2mtrs deep. The length of a manually operated. lock on the Shannon Navigation is 29.2mtrs and 1.35mtrs deep. Ballinamore Lock im aterway this Lock . Leitr Located on the Shannon-Erne W n in Co ck raulic lock operated by boat users gh Alle ulic lo lock is a hyd Drumshanbon Lou ydra ugh the use of a smart card cated o ock is a h thro Lo anbo L eeper rumsh ock-K D ed by a L operat The Grand Canal 30th Lock Did you know? Located on the Grand Canal the 30th Lock is operated manually through the use of a lock A lock is a device for raising key and lowering boats between stretches of water of different levels on rivers and canals. Activity Arrange a visit to your nearest lock and find out the following information: a. The name of the lock? b. Is it a manual or automated lock? c. How old is the lock? d. -

3 Record of Protected Structures

APPENDIX 3 RECORD OF PROTECTED STRUCTURES Record of Protected Structures (RPS) incorporating the Naas and Athy RPS 56 Kildare County Development Plan 2017-2023 Kildare County Development Plan 2017-2023 57 RECORD OF PROTECTED STRUCTURES PROPOSED PROTECTED STRUCTURES Record of Protected Structures (RPS) Each Development Plan must include objectives for A ‘proposed protected structure’ is a structure whose the protection of structures or parts of structures owner or occupier has received notification of the Table A3.1 CountyKildare Record of Protected Structures (excluding Naas and Athy) of special interest. The primary means of achieving intention of the planning authority to include it on these objectives is for the planning authority the RPS. Most of the protective mechanisms under RPS No. NIAH Structure Name Townland Description 6” to compile and maintain a record of protected the Planning and Development Acts and Regulations Ref. Map structures (RPS) for its functional area and which apply equally to protected structures and proposed B01-01 Ballynakill Rath Ballynakill Rath 1 is included in the plan. A planning authority is protected structures. obliged to include in the RPS structures which, in B01-02 11900102 Ballyonan Corn Mill Ballyonan Corn Mill 1 Once a planning authority notifies an owner or its opinion, are of special architectural, historical, B01-03 11900101 Leinster Bridge, Co. Kildare Clonard New Bridge 1 archaeological, artistic, cultural, scientific, social or occupier of the proposal to add a particular structure B02-01 Carrick Castle Carrick Castle 2 technical interest. This responsibility will involve to the RPS, protection applies to that proposed the planning authority reviewing its RPS from time protected structure during the consultation period, B02-02 Brackagh Holy Well - “Lady Well” Brackagh Holy Well 2 to time (normally during the review of the County pending the final decision of the planning authority. -

Bert House Stud, Bert Demesne, Athy, Co. Kildare on C. 58 Acres (23.47 Ha) PSRA Reg

A FINE EQUESTRIAN PROPERTY SITUATED ON TOP CLASS LAND IN SOUTH KILDARE WITH EXTENSIVE ANCILLARY FACILITIES ___________________________________________________________________ Bert House Stud, Bert Demesne, Athy, Co. Kildare on c. 58 Acres (23.47 Ha) PSRA Reg. No. 001536 GUIDE PRICE: €1,300,000 GUIDE PRICE: € 1,250,000 FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY SERVICES: Bert House Stud, Bert Demesne, Athy, Private and public water, septic tank drainage, oil fired central heating. Co. Kildare, R14 P034 AMENITIES: ____________________________________ Hunting: with the Kildares, the Carlows and the Tara DESCRIPTION: The property is situated north of Athy at the Village of Harriers all within boxing distances. Kilberry. Athy is located in South Kildare which is Racing: Curragh, Naas, Punchestown and easily accessible from the M7 at Monasterevin and from Leopardstown. Golf: Athy, Carlow, The Curragh and Rathsallagh. M9 at Ballitore Exit 3. DIRECTIONS: The land comprises c. 58 acres (23.47 ha) and is all top quality with no waste and is classified under the Athy From Dublin and the South via the M7 continue on the M7 and at Exit at Junction 14 for the R445 Monasterevin Series in the Soils of Co. Kildare which is basically predominantly limestone. The property is suitable as a -Tullamore. Continue on the R445 taking the third exit at the roundabout and go through the next roundabout stud farm but also ideal for a sport horse enthusiast, sales prep, and racing yard. There is a total of 58 boxes and then left on to the R445. Turn left on to the R417 in a rectangular courtyard layout with automatic and proceed for approximately 12.8 km on this road horsewalker, sand gallops, 5 staff cottages, office, where the property for sale is on the right in Kilberry canteen and many ancillary facilities. -

Representative Church Body Library, Dublin C.2 Muniments of St

Representative Church Body Library, Dublin C.2 Muniments of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin 13th-20th cent. Transferred from St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, 1995-2002, 2012 GENERAL ARRANGEMENT C2.1. Volumes C2.2. Deeds C2.3. Maps C2.4. Plans and Drawings C2.5. Loose Papers C2.6. Photographs C.2.7. Printed Material C.2.8. Seals C.2.9. Music 2 1. VOLUMES 1.1 Dignitas Decani Parchment register containing copies of deeds and related documents, c.1190- 1555, early 16th cent., with additions, 1300-1640, by the Revd John Lyon in the 18th cent. [Printed as N.B. White (ed) The Dignitas Decani of St Patrick's cathedral, Dublin (Dublin 1957)]. 1.2 Copy of the Dignitas Decani An early 18th cent. copy on parchment. 1.3 Chapter Act Books 1. 1643-1649 (table of contents in hand of John Lyon) 2. 1660-1670 3. 1670-1677 [This is a copy. The original is Trinity College, Dublin MS 555] 4. 1678-1690 5. 1678-1713 6. 1678-1713 (index) 7. 1690-1719 8. 1720-1763 (table of contents) 9. 1764-1792 (table of contents) 10. 1793-1819 (table of contents) 11. 1819-1836 (table of contents) 12. 1836-1860 (table of contents) 13. 1861-1982 1.4 Rough Chapter Act Books 1. 1783-1793 2. 1793-1812 3. 1814-1819 4. 1819-1825 5. 1825-1831 6. 1831-1842 7. 1842-1853 8. 1853-1866 9. 1884-1888 1.5 Board Minute Books 1. 1872-1892 2. 1892-1916 3. 1916-1932 4. 1932-1957 5. -

CLOSING 12 NOON WEDNESDAY 27Th MAY CLOSING 12 NOON

Under the Rules of Racing G 7:15 pm Under the Rules of Racing The Irish Lincolnshire of €75,000 FRIDAY and SATURDAY - JUNE 12th (E) and CURRAGH (Premier Handicap) 13th (E), 2020 Winner will receive €45,000 (Penalty Value: €44,310) Meeting No. 122 CURRAGH Second will receive €15,000 Third will receive €7,500 SECOND DAY - SATURDAY, 13th JUNE Meeting No. 121 Fourth will receive €3,750 (Evening Meeting) Fifth will receive €2,250 FIRST DAY - FRIDAY, 12th JUNE Sixth will receive €1,500 An extended handicap for four years old and CLOSING 12 NOON (Evening Meeting) upwards that have run at least three times WEDNESDAY 27th MAY under any Rules of Racing before 1st June, CLOSING 12 NOON 2020, at least one of those runs having been Handicaps calculated ........................... 9th June on or after 1st May, 2019 WEDNESDAY 27th MAY Rating Qualification .............................. 9th June (105 = 10st) Declarations to run must be made by 10am Handicaps calculated for Top weight in the original handicap and Thursday 11th June The Irish Lincolnshire ....................... 2nd June after the time of declaration shall not be less Rating Qualification ............................. 26th May than 10st and the minimum weight is 8st CEO ............................................ Mr. Pat Keogh Other Handicaps calculated ................. 8th June 6lbs Racing Manager ................... Mr. Evan Arkwright Rating Qualification ............................. 2nd June About 1 mile Handicappers ........................... Mr.G.O'Gorman Declarations to run must be made by 10am Maximum Runners: 18 . .................................................... Mr.Mark Bird Wednesday 10th June €300 to enter on May 27th | €240 extra if forfeit not declared by June 8th | and €150 extra if NOTICE CEO........................................... -

Carlow College

- . - · 1 ~. .. { ~l natp C u l,•< J 1 Journal of the Old Carlow Society 1992/1993 lrisleabhar Chumann Seanda Chatharlocha £1 ' ! SERVING THE CHURCH FOR 200 YEARS ! £'~,~~~~::~ai:~:,~ ---~~'-~:~~~ic~~~"'- -· =-~ : -_- _ ~--~~~- _-=:-- ·.. ~. SPONSORS ROYAL HOTEL- 9-13 DUBLIN STREET ~ P,•«•11.il H,,rd ,,,- Qua/in- O'NEILL & CO. ACCOUNTANTS _;, R-.. -~ ~ 'I?!~ I.-: _,;,r.',". ~ h,i14 t. t'r" rhr,•c Con(crcncc Roonts. TRAYNOR HOUSE, COLLEGE STREET, CARLOW U • • i.h,r,;:, F:..n~ r;,,n_,. f)lfmt·r DL1nccs. PT'i,·atc Parties. Phone:0503/41260 F."-.l S,:r.cJ .-\II Da,. Phone 0503/31621. t:D. HAUGHNEY & SON, LTD. Jewellers, ·n~I, Fashion Boutique, Fuel Merchant. Authorised Ergas Stockist ·~ff 62-63 DUBLIN ST., CARLOW POLLERTON ROAD, CARLOW. Phone 0503/31367 OF CARLOW Phone:0503/31346 CIGAR DIVAN TULL Y'S TRAVEL AGENCY Newsagent, Confectioner, Tobacconist, etc. TULLOW STREET, CARLOW DUBLIN STREET, CARLOW Phone:0503/31257 Bring your friends to a musical evening in Carlow's unique GACH RATH AR CARLOVIANA Music Lounge each Saturday and Sunday. Phone: 0503/27159. ST. MARY'S ACADEMY, SMYTHS of NEWTOWN CARLOW SINCE 1815 DEERPARK SERVICE STATION MICHAEL DOYLE Builders Providers, General Hardware Tyre Service and Accessories 'THE SHAMROCK", 71 TULLOW STREET, CARLOW DUBLIN ROAD, CARLOW. Phone 0503/31414 Phone:0503/31847 THOMAS F. KEHOE SEVEN OAKS HOTEL Specialist Livestock Auctioneer and Valuer, Far, Sales and Lettings,. Property and Est e Agent. Dinner Dances * Wedding Receptions * Private Parties Agent for the Irish Civil Ser- ce Building Society. Conferences * Luxury Lounge 57 DUBLIN STREET, CARLOW. Telephone 0503/31678, 31963. -

Woodstock South, Athy, Co. Kildare. Approx

FOR SALE BY PUBLIC TENDER WOODSTOCK SOUTH, ATHY, CO. KILDARE. APPROX. 2.88 HA. (7 ACRES) • Strategic Site with good profile. BUSINESS CAMPUS TOWN CENTRE • Excellent accessibility to M7 & M9 motorways. MINCH MALT • Zoned ‘R’- retail / commercial with full Planning Permission in place for 3,375 sq.m retail store. • Adjoining occupiers TEGRAL include Minch Malt, Tegral, Woodstock Ind Estate and the Athy Business Campus. • Medium - Long term investment potential. • New Outer Relief Road will further improve N78 accessibility. Auctioneers, Estate Agents & Chartered Valuation Surveyors Tel: 045-433550 PRIME DEVELOPMENT SITE www.jordancs.ie WOODSTOCK SOUTH, ATHY, CO. KILDARE. M1 RAILWAY LINE RAILWAY LINE M3 CLONEE/ DUNBOYNE LOCATION: TITLE: KILCOCK The property is located in the townsland of Woodstock South about Freehold. N4 LEIXLIP MAYNOOTH 600 metres to the west of the town centre & just off the N78. Adjoining M4 DUBLIN SOLICITORS: CELBRIDGE occupiers include Minch Malt, Tegral, Woodstock Industrial Estate & RAILWAY LINE the Athy Business Campus. Arthur Cox, Earlsfort Centre, Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2. CLANE Athy which has a population of approximately 9,000 people occupies Tel: 01 – 6180370 – ref: Ms Deirdre Durcan. SALLINS M50 RATHANGAN KILL a good central location approximately 70 km south east of Dublin, M7 TENDER PROCEDURE: NEWBRIDGE NAAS 35 km south of Naas, 25 km east of Portlaoise, and 18 km north of RAILWAY LINE BALLYMORE EUSTACE Carlow. Athy is served by both bus and rail public transport. The rail Tenders to be submitted to the offices of KILCULLEN service includes the mainline intercity service on the Carlow/ Kilkenny Arthur Cox, Earlsfort Centre, MONASTEREVIN Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2 WOODSTOCK, M7 KILDARE / Waterford line.