Voodoo Macbeth”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacksonville Review

JACKSONVILLE March 2020 • Lifestyle Magazine • JacksonvilleReview.com 8387 UPPER APPLEGATE, JACKSONVILLE 2241 TEMPLE DRIVE, MEDFORD 440 CONESTOGA, JACKSONVILLE 8026 UPPER APPLEGATE, JACKSONVILLE REVIEW GORGEOUS RIVER-FRONT HOME WONDERFUL EAST MEDFORD GORGEOUS SHOWSTOPPER HOME COZY APPLEGATE MOUNTAIN BURSTING WITH NATURAL LIGHT! LOCATION, CLOSE TO SCHOOLS, WITH DIRECT ACCESS TO WOODLAND HOME WITH ADU GUEST COTTAGE OVER GARAGE SHOPPING, AND MEDICAL OFFICES TRAIL SYSTEM 3 BD 2.5 BA, 3.69 ACRES 3 BD, 3 BA, 2,433 Sq Ft, 2.73 Acres 3 BD 2 BA, 1,188 Sq Ft 4 BD 3.5 BA 4,494 Sq Ft .5 acre 2,289 COMBINED Sq Ft $785,000 | MLS 3008260 $265,000 | MLS 3010273 $650,000 | MLS 3009991 $469,000 | MLS 3009287 1700 ANDREWS PL, JACKSONVILLE 802 NEWTOWN STREET, MEDFORD 7756 UPPER APPLEGATE, JACKSONVILLE 415 NUGGET DR, ROGUE RIVER NEW PRICE! BEAUTIFUL, PRIVATE .5 ACRE LOT CHARM ABOUNDS IN THIS BEAUTIFUL FARMHOUSE IN THE CHARMING ROGUE RIVER HOME WITH INCREDIBLE VIEWS OF THE ADORABLE, RETRO- INSPIRED APPLEGATE VALLEY. GREAT SURROUNDED BY BEAUTIFUL MOUNTAINS AND SURROUNDING COTTAGE! POTENTIAL FOR HORSE PROPERTY! MOUNTAIN VIEWS WOODED SCENERY 2 BED 1 BATH 1,200 Sq Ft 4 BD, 2.5 BA, 2,100 Sq Ft, 4.92 Acres 3BD 1.5 BA, 1,140 SQ FT $179,500 | MLS 3007478 $220,000 | MLS 3009773 $549,900 | MLS 2995038 $269,900 | MLS 3010261 280 WELLS FARGO DR, JACKSONVILLE 2106 KNOWLES ROAD, MEDFORD 660 CARRIAGE LANE, JACKSONVILLE DON’T SETTLE – BUILD THE HOUSE YOU WANT IN TIMBER RIDGE Pending! Timber R dge ESTATES www.TimberRidgeOr.com BUILD YOUR DREAM HOME ON TOP OF THE WORLD LIVING -

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies –

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan Published by Self Improvement Online, Inc. http://www.SelfGrowth.com 20 Arie Drive, Marlboro, NJ 07746 ©Copyright by David Riklan Manufactured in the United States No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Limit of Liability / Disclaimer of Warranty: While the authors have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents and specifically disclaim any implied warranties. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. The author shall not be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Spiritual Cinema 8 About SelfGrowth.com 10 Newer Inspirational Movies 11 Ranking Movie Title # 1 It’s a Wonderful Life 13 # 2 Forrest Gump 16 # 3 Field of Dreams 19 # 4 Rudy 22 # 5 Rocky 24 # 6 Chariots of -

Me and Orson Welles Press Kit Draft

presents ME AND ORSON WELLES Directed by Richard Linklater Based on the novel by Robert Kaplow Starring: Claire Danes, Zac Efron and Christian McKay www.meandorsonwelles.com.au National release date: July 29, 2010 Running time: 114 minutes Rating: PG PUBLICITY: Philippa Harris NIX Co t: 02 9211 6650 m: 0409 901 809 e: [email protected] (See last page for state publicity and materials contacts) Synopsis Based in real theatrical history, ME AND ORSON WELLES is a romantic coming‐of‐age story about teenage student Richard Samuels (ZAC EFRON) who lucks into a role in “Julius Caesar” as it’s being re‐imagined by a brilliant, impetuous young director named Orson Welles (impressive newcomer CHRISTIAN MCKAY) at his newly founded Mercury Theatre in New York City, 1937. The rollercoaster week leading up to opening night has Richard make his Broadway debut, find romance with an ambitious older woman (CLAIRE DANES) and eXperience the dark side of genius after daring to cross the brilliant and charismatic‐but‐ sometimes‐cruel Welles, all‐the‐while miXing with everyone from starlets to stagehands in behind‐the‐scenes adventures bound to change his life. All’s fair in love and theatre. Directed by Richard Linklater, the Oscar Nominated director of BEFORE SUNRISE and THE SCHOOL OF ROCK. PRODUCTION I NFORMATION Zac Efron, Ben Chaplin, Claire Danes, Zoe Kazan, Eddie Marsan, Christian McKay, Kelly Reilly and James Tupper lead a talented ensemble cast of stage and screen actors in the coming‐of‐age romantic drama ME AND ORSON WELLES. Oscar®‐nominated director Richard Linklater (“School of Rock”, “Before Sunset”) is at the helm of the CinemaNX and Detour Filmproduction, filmed in the Isle of Man, at Pinewood Studios, on various London locations and in New York City. -

Black Soldiers in Liberal Hollywood

Katherine Kinney Cold Wars: Black Soldiers in Liberal Hollywood n 1982 Louis Gossett, Jr was awarded the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of Gunnery Sergeant Foley in An Officer and a Gentleman, becoming theI first African American actor to win an Oscar since Sidney Poitier. In 1989, Denzel Washington became the second to win, again in a supporting role, for Glory. It is perhaps more than coincidental that both award winning roles were soldiers. At once assimilationist and militant, the black soldier apparently escapes the Hollywood history Donald Bogle has named, “Coons, Toms, Bucks, and Mammies” or the more recent litany of cops and criminals. From the liberal consensus of WWII, to the ideological ruptures of Vietnam, and the reconstruction of the image of the military in the Reagan-Bush era, the black soldier has assumed an increasingly prominent role, ironically maintaining Hollywood’s liberal credentials and its preeminence in producing a national mythos. This largely static evolution can be traced from landmark films of WWII and post-War liberal Hollywood: Bataan (1943) and Home of the Brave (1949), through the career of actor James Edwards in the 1950’s, and to the more politically contested Vietnam War films of the 1980’s. Since WWII, the black soldier has held a crucial, but little noted, position in the battles over Hollywood representations of African American men.1 The soldier’s role is conspicuous in the way it places African American men explicitly within a nationalist and a nationaliz- ing context: U.S. history and Hollywood’s narrative of assimilation, the combat film. -

The Magnificent Ambersons Review

The magnificent ambersons review Continue For the 2002 television version, watch The Magnificent Amberers (the 2002 film). 1942 film by Orson Helles, Robert Wise Magnificent AmbersonsTheatrical release poster with illustrations by Norman Rockwell 1Director Orson WellesProduced Orson WellesScreenplay Orson WellesBased on Magnificent Amberersby Booth TarkingtonStarring Joseph Cotten Dostren Dolores Costello Ann Baxter Tim Holt Agnes Moorhead Ray Collins Erskine Sanford Richard Bennett Comments Orson WellesMusic No Credit to FilmCinematographyStanley CortezEd ByRobert WiseProductioncompany RKO Radio PicturesMercury Productions Distributed RKO Radio PicturesRelease Date July 10 , 1942 (1942-07-10) Running time 88 minutes148 minutes (original)131 minutes (preview)Country Of the United StatesLanguageEnglishBudget $1.1 million:71-72Box office $1 million (US rent) The Magnificent Ambers (U.S. - American drama 1942, written, produced and directed by Orson Velez. Welles will adapt Booth Tarkington's Pulitzer Prize-winning 1918 novel, about the leaning fortunes of the wealthy Midwestern family and the social changes brought by the car era. The film stars Joseph Cotten, Dolores Costello, Ann Baxter, Tim Holt, Agnes Moorhead and Ray Collins, while Welles has a narration. Heles lost control of RKO's The Magnificent Amberers edit, and the final version released to viewers was significantly different from his rough cut of the film. More than an hour of footage was cut in the studio, which also shot and replaced a happier ending. While Veles's extensive notes on how he wanted the film to be shortened survived, the cut frames were destroyed. Composer Bernard Herrmann insisted that his merit be removed when, like the film itself, his score was heavily edited by the studio. -

Orson Welles: CHIMES at MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 Min

October 18, 2016 (XXXIII:8) Orson Welles: CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 min. Directed by Orson Welles Written by William Shakespeare (plays), Raphael Holinshed (book), Orson Welles (screenplay) Produced by Ángel Escolano, Emiliano Piedra, Harry Saltzman Music Angelo Francesco Lavagnino Cinematography Edmond Richard Film Editing Elena Jaumandreu , Frederick Muller, Peter Parasheles Production Design Mariano Erdoiza Set Decoration José Antonio de la Guerra Costume Design Orson Welles Cast Orson Welles…Falstaff Jeanne Moreau…Doll Tearsheet Worlds" panicked thousands of listeners. His made his Margaret Rutherford…Mistress Quickly first film Citizen Kane (1941), which tops nearly all lists John Gielgud ... Henry IV of the world's greatest films, when he was only 25. Marina Vlady ... Kate Percy Despite his reputation as an actor and master filmmaker, Walter Chiari ... Mr. Silence he maintained his memberships in the International Michael Aldridge ...Pistol Brotherhood of Magicians and the Society of American Tony Beckley ... Ned Poins and regularly practiced sleight-of-hand magic in case his Jeremy Rowe ... Prince John career came to an abrupt end. Welles occasionally Alan Webb ... Shallow performed at the annual conventions of each organization, Fernando Rey ... Worcester and was considered by fellow magicians to be extremely Keith Baxter...Prince Hal accomplished. Laurence Olivier had wanted to cast him as Norman Rodway ... Henry 'Hotspur' Percy Buckingham in Richard III (1955), his film of William José Nieto ... Northumberland Shakespeare's play "Richard III", but gave the role to Andrew Faulds ... Westmoreland Ralph Richardson, his oldest friend, because Richardson Patrick Bedford ... Bardolph (as Paddy Bedford) wanted it. In his autobiography, Olivier says he wishes he Beatrice Welles .. -

Antihero- Level 2 Theme 2008

DEFINITION AND TEXT LIST - ENGLISH - LITERATURE Teenage Anti-Hero UNIT STANDARD 8823 version 4 4 Credits - Level 2 (Reading) Investigate a theme across an inclusive range of selected texts Characteristics in protagonists that merit the label “Anti-hero” can include, but are not limited to: • imperfections that separate them from typically "heroic" characters (selfishness, ignorance, bigotry, etc.); • lack of positive qualities such as "courage, physical prowess, and fortitude," and "generally feel helpless in a world over which they have no control"; • qualities normally belonging to villains (amorality, greed, violent tendencies, etc.) that may be tempered with more human, identifiable traits (confusion, self-hatred, etc.); • noble motives pursued by bending or breaking the law in the belief that "the ends justify the means." Literature • Roland Deschain from Stephen King's The Dark Tower series Alex, the narrator of Anthony Burgess' A Clockwork • Raoul Duke from Hunter S. Thompson's Fear and Orange. • Loathing in Las Vegas Redmond Barry from William Makepeace • Tyler Durden and the Narrator of Chuck Palahniuk's Thackeray's The Luck of Barry Lyndon • Fight Club Patrick Bateman from Bret Easton Ellis' American • Randall Flagg from Stephen King's The Stand, Eyes of Psycho. • the Dragon and The Dark Tower. Leopold Bloom from James Joyce's Ulysses. • Artemis Fowl II from the Artemis Fowl series. Pinkie Brown from Graham Greene's Brighton Rock. • • Gully Foyle from Alfred Bester's The Stars My Holden Caulfield from J.D. Salinger's Catcher in the • • Destination Rye. Victor Frankenstein from Mary Shelley's Conan from the stories by Robert E. Howard, the • • Frankenstein archetypal "amoral swordsman" of the Sword and Jay Gatsby from F. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum 4079 Albany Post Road, Hyde Park, NY 12538-1917 www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu 1-800-FDR-VISIT October 14, 2008 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Cliff Laube (845) 486-7745 Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library Author Talk and Film: Susan Quinn Furious Improvisation: How the WPA and a Cast of Thousands Made High Art out of Desperate Times HYDE PARK, NY -- The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum is pleased to announce that Susan Quinn, author of Furious Improvisation: How the WPA and a Cast of Thousands Made High Art out of Desperate Times, will speak at the Henry A. Wallace Visitor and Education Center on Sunday, October 26 at 2:00 p.m. Following the talk, Ms. Quinn will be available to sign copies of her book. Furious Improvisation is a vivid portrait of the turbulent 1930s and the Roosevelt Administration as seen through the Federal Theater Project. Under the direction of Hallie Flanagan, formerly of the Vassar Experimental Theatre in Poughkeepsie, New York, the Federal Theater Project was a small but highly visible part of the vast New Deal program known as the Works Projects Administration. The Federal Theater Project provided jobs for thousands of unemployed theater workers, actors, writers, directors and designers nurturing many talents, including Orson Welles, John Houseman, Arthur Miller and Richard Wright. At the same time, it exposed a new audience of hundreds of thousands to live theatre for the first time, and invented a documentary theater form called the Living Newspaper. In 1939, the Federal Theater Project became one of the first targets of the newly-formed House Un-American Activities Committee, whose members used unreliable witnesses to demonstrate that it was infested with Communists. -

The Booklet That Accompanied the Exhibition, With

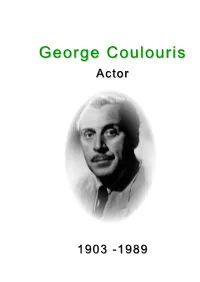

GGeeoorrggee CCoouulloouurriiss AAccttoorr 11990033 --11998899 George Coulouris - Biographical Notes 1903 1st October: born in Ordsall, son of Nicholas & Abigail Coulouris c1908 – c1910: attended a local private Dame School c1910 – 1916: attended Pendleton Grammar School on High Street c1916 – c1918: living at 137 New Park Road and father had a restaurant in Salisbury Buildings, 199 Trafford Road 1916 – 1921: attended Manchester Grammar School c1919 – c1923: father gave up the restaurant Portrait of George aged four to become a merchant with offices in Salisbury Buildings. George worked here for a while before going to drama school. During this same period the family had moved to Oakhurst, Church Road, Urmston c1923 – c1925: attended London’s Central School of Speech and Drama 1926 May: first professional stage appearance, in the Rusholme (Manchester) Repertory Theatre’s production of Outward Bound 1926 October: London debut in Henry V at the Old Vic 1929 9th Dec: Broadway debut in The Novice and the Duke 1933: First Hollywood film Christopher Bean 1937: played Mark Antony in Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre production of Julius Caesar 1941: appeared in the film Citizen Kane 1950 Jan: returned to England to play Tartuffe at the Bristol Old Vic and the Lyric Hammersmith 1951: first British film Appointment With Venus 1974: played Dr Constantine to Albert Finney’s Poirot in Murder On The Orient Express. Also played Dr Roth, alongside Robert Powell, in Mahler 1989 25th April: died in Hampstead John Koulouris William Redfern m: c1861 Louisa Bailey b: 1832 Prestbury b: 1842 Macclesfield Knutsford Nicholas m: 10 Aug 1902 Abigail Redfern Mary Ann John b: c1873 Stretford b: 1864 b: c1866 b: c1861 Greece Sutton-in-Macclesfield Macclesfield Macclesfield d: 1935 d: 1926 Urmston George Alexander m: 10 May 1930 Louise Franklin (1) b: Oct 1903 New York Salford d: April 1989 d: 1976 m: 1977 Elizabeth Donaldson (2) George Franklin Mary Louise b: 1937 b: 1939 Where George Coulouris was born Above: Trafford Road with Hulton Street going off to the right. -

September 2019 Open House Precedes Wrecking Transition Town Ball for Former St

St. AnthonyYour Park Park award-winning,Falcon Heights nonprofitLauderdale community Como Park resource St.www.parkbugle.org Anthony Park / Falcon Heights www.parkbugle.org BugleLauderdale / Como Park September 2019 Open house precedes wrecking Transition Town ball for former St. Andrew’s Church Model farm explored By Scott Carlson sons, said about the open house. Page 8 “I am hopeful that we will be able The open house last month for to mend relationships.” the former St. Andrew’s Church For his part, Fauskee ap- in the Como neighborhood held preciated the gesture. “Thanks special meaning for Tom Fauskee. for doing the open house,” he “We were parishioners here,” told Alkatout. But across the Fauskee said, noting the church street from the church build- was where he sang in the men’s ing, protesters held placards chorus and where he and his wife that implored school officials to renewed wedding vows on their reverse course and not raze the 30th anniversary. “In the end it former church building, which [former church] is just brick-and- the school converted into a mortar,” he mused. gymnasium. On the last Sunday afternoon “We are very sad,” said Di- in July, Fauskee was among scores anne Miron, who grew up in the of people who stopped by to rem- Warrendale neighborhood and inisce and say goodbye to the for- went to school at the church. mer Catholic church before the “They are tearing down some- Twin Cities German Immersion thing culturally important to this School, the current property own- neighborhood.” er, was scheduled to raze the struc- That preservationists bat- ture for a new school building. -

Fiery Speech in a World of Shadows: Rosebud's Impact on Early Audiences Author(S): Robin Bates and Scott Bates Source: Cinema Journal, Vol

Society for Cinema & Media Studies Fiery Speech in a World of Shadows: Rosebud's Impact on Early Audiences Author(s): Robin Bates and Scott Bates Source: Cinema Journal, Vol. 26, No. 2 (Winter, 1987), pp. 3-26 Published by: University of Texas Press on behalf of the Society for Cinema & Media Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1225336 Accessed: 17-06-2016 15:02 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1225336?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Texas Press, Society for Cinema & Media Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Cinema Journal This content downloaded from 128.91.220.36 on Fri, 17 Jun 2016 15:02:42 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Fiery Speech in a World of Shadows: Rosebud's Impact on Early Audiences by Robin Bates with Scott Bates When I first saw Citizen Kane with my college friends in 1941, it was in an America undergoing the powerful pressures of a coming war, full of populist excitement and revolutionary foreboding. -

Anti-Apartheid Solidarity in United States–South Africa Relations: from the Margins to the Mainstream

Anti-apartheid solidarity in United States–South Africa relations: From the margins to the mainstream By William Minter and Sylvia Hill1 I came here because of my deep interest and affection for a land settled by the Dutch in the mid-seventeenth century, then taken over by the British, and at last independent; a land in which the native inhabitants were at first subdued, but relations with whom remain a problem to this day; a land which defined itself on a hostile frontier; a land which has tamed rich natural resources through the energetic application of modern technology; a land which once imported slaves, and now must struggle to wipe out the last traces of that former bondage. I refer, of course, to the United States of America. Robert F. Kennedy, University of Cape Town, 6 June 1966.2 The opening lines of Senator Robert Kennedy’s speech to the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS), on a trip to South Africa which aroused the ire of pro-apartheid editorial writers, well illustrate one fundamental component of the involvement of the United States in South Africa’s freedom struggle. For white as well as black Americans, the issues of white minority rule in South Africa have always been seen in parallel with the definition of their own country’s identity and struggles against racism.3 From the beginning of white settlement in the two countries, reciprocal influences have affected both rulers and ruled. And direct contacts between African Americans and black South Africans date back at least to the visits of American 1 William Minter is editor of AfricaFocus Bulletin (www.africafocus.org) and a writer and scholar on African issues.