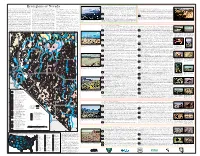

Mapping Perennial Vegetation Cover in the Mojave Desert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M O J a V E D E S E R T I S S U E S a Secondary

MOJAVE DESERT ISSUES A Secondary School Curriculum Bruce W. Bridenbecker & Darleen K. Stoner, Ph.D. Research Assistant Gail Uchwat Mojave Desert Issues was funded with a grant from the National Park �� Foundation. Parks as Classrooms is the educational program of the National ����� �� ���������� Park Service in partnership with the National Park Foundation. Design by Amy Yee and Sandra Kaye Published in 1999 and printed on recycled paper ii iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to the following people for their contribution to this work: Elayn Briggs, Bureau of Land Management Caryn Davidson, National Park Service Larry Ellis, Banning High School Lorenza Fong, National Park Service Veronica Fortun, Bureau of Land Management Corky Hays, National Park Service Lorna Lange-Daggs, National Park Service Dave Martell, Pinon Mesa Middle School David Moore, National Park Service Ruby Newton, National Park Service Carol Peterson, National Park Service Pete Ricards, Twentynine Palms Highschool Kay Rohde, National Park Service Dennis Schramm, National Park Service Jo Simpson, Bureau of Land Management Kirsten Talken, National Park Service Cindy Zacks, Yucca Valley Highschool Joe Zarki, National Park Service The following specialists provided information: John Anderson, California Department of Fish & Game Dave Bieri, National Park Service �� John Crossman, California Department of Parks and Recreation ����� �� ���������� Don Fife, American Land Holders Association Dana Harper, National Park Service Judy Hohman, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Becky Miller, California -

Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 Is a Mountainous, Deeply Dissected, and Westerly Tilting Fault Block

5 . S i e r r a N e v a d a Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 is a mountainous, deeply dissected, and westerly tilting fault block. It is largely composed of granitic rocks that are lithologically distinct from the sedimentary rocks of the Klamath Mountains (78) and the volcanic rocks of the Cascades (4). A Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, Vegas, Reno, and Carson City areas. Most of the state is internally drained and lies Literature Cited: high fault scarp divides the Sierra Nevada (5) from the Northern Basin and Range (80) and Central Basin and Range (13) to the 2 2 . A r i z o n a / N e w M e x i c o P l a t e a u east. Near this eastern fault scarp, the Sierra Nevada (5) reaches its highest elevations. Here, moraines, cirques, and small lakes and quantity of environmental resources. They are designed to serve as a spatial within the Great Basin; rivers in the southeast are part of the Colorado River system Bailey, R.G., Avers, P.E., King, T., and McNab, W.H., eds., 1994, Ecoregions and subregions of the Ecoregion 22 is a high dissected plateau underlain by horizontal beds of limestone, sandstone, and shale, cut by canyons, and United States (map): Washington, D.C., USFS, scale 1:7,500,000. are especially common and are products of Pleistocene alpine glaciation. Large areas are above timberline, including Mt. Whitney framework for the research, assessment, management, and monitoring of ecosystems and those in the northeast drain to the Snake River. -

Synoptic-Scale Control Over Modern Rainfall and Flood Patterns in the Levant Drylands with Implications for Past Climates

JUNE 2018 ARMONETAL. 1077 Synoptic-Scale Control over Modern Rainfall and Flood Patterns in the Levant Drylands with Implications for Past Climates MOSHE ARMON Fredy and Nadine Herrmann Institute of Earth Sciences, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Givat Ram, Jerusalem, Israel ELAD DENTE Fredy and Nadine Herrmann Institute of Earth Sciences, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Givat Ram, and Geological Survey of Israel, Jerusalem, Israel JAMES A. SMITH Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey YEHOUDA ENZEL AND EFRAT MORIN Fredy and Nadine Herrmann Institute of Earth Sciences, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Givat Ram, Jerusalem, Israel (Manuscript received 23 January 2018, in final form 1 May 2018) ABSTRACT Rainfall in the Levant drylands is scarce but can potentially generate high-magnitude flash floods. Rainstorms are caused by distinct synoptic-scale circulation patterns: Mediterranean cyclone (MC), active Red Sea trough (ARST), and subtropical jet stream (STJ) disturbances, also termed tropical plumes (TPs). The unique spatiotemporal char- acteristics of rainstorms and floods for each circulation pattern were identified. Meteorological reanalyses, quantitative precipitation estimates from weather radars, hydrological data, and indicators of geomorphic changes from remote sensing imagery were used to characterize the chain of hydrometeorological processes leading to distinct flood patterns in the region. Significant differences in the hydrometeorology of these three flood-producing synoptic systems were identified: MC storms draw moisture from the Mediterranean and generate moderate rainfall in the northern part of the region. ARST and TP storms transfer large amounts of moisture from the south, which is converted to rainfall in the hyperarid southernmost parts of the Levant. -

North American Deserts Chihuahuan - Great Basin Desert - Sonoran – Mojave

North American Deserts Chihuahuan - Great Basin Desert - Sonoran – Mojave http://www.desertusa.com/desert.html In most modern classifications, the deserts of the United States and northern Mexico are grouped into four distinct categories. These distinctions are made on the basis of floristic composition and distribution -- the species of plants growing in a particular desert region. Plant communities, in turn, are determined by the geologic history of a region, the soil and mineral conditions, the elevation and the patterns of precipitation. Three of these deserts -- the Chihuahuan, the Sonoran and the Mojave -- are called "hot deserts," because of their high temperatures during the long summer and because the evolutionary affinities of their plant life are largely with the subtropical plant communities to the south. The Great Basin Desert is called a "cold desert" because it is generally cooler and its dominant plant life is not subtropical in origin. Chihuahuan Desert: A small area of southeastern New Mexico and extreme western Texas, extending south into a vast area of Mexico. Great Basin Desert: The northern three-quarters of Nevada, western and southern Utah, to the southern third of Idaho and the southeastern corner of Oregon. According to some, it also includes small portions of western Colorado and southwestern Wyoming. Bordered on the south by the Mojave and Sonoran Deserts. Mojave Desert: A portion of southern Nevada, extreme southwestern Utah and of eastern California, north of the Sonoran Desert. Sonoran Desert: A relatively small region of extreme south-central California and most of the southern half of Arizona, east to almost the New Mexico line. -

Rose-Marcella-Thesis-2020.Pdf

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Nebkha Morphology, Distribution and Stability Black Rock Playa, Nevada A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Geography By Marcella Rose December 2019 The thesis of Marcella Rose is approved: _______________________________________ _____________ Dr. Julie Laity Date _______________________________________ _____________ Dr. Thomas Farr Date _______________________________________ _____________ Dr. Amalie Orme, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Acknowledgements Dr. Orme, I really don’t think that there is a sufficient combination of words that exist to properly express the immense amount of gratitude I feel for everything that you have done for me. This college education changed my life for the better and I hope you realize what a significant role you were within that experience. I am thankful that not only did I get a great professor, but also a friend. Dr. Laity, thank you so much for having faith in me and for taking me on as one of your last students to advise. But most of all, thank you for pushing me to be better – I needed that. Dr. Farr, I was so excited during DEVELOP that you accepted to be a part of my committee. It was a pleasure to work with you within the Black Rock Playa research team but then to also take our research a step further for this graduate thesis. I would also like to thank the staff at the Bureau of Land Management, Winnemucca: Dr. Mark E. Hall, Field Manager of the Black Rock Field Office; Shane Garside, Black Rock Station Manager/ Outdoor Recreation Planner; Brian McMillan, Rangeland Management Technician; and Braydon Gaard, Interim Outdoor Recreation Planner. -

Mojave Desert Native Plant Program Mojave Desert Restoration Challenges: It’S Hot and Dry!

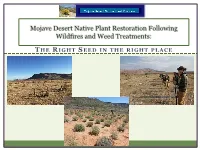

Mojave Desert Native Plant Restoration Following Wildfires and Weed Treatments: T HE RIGHT S EED IN THE RIGHT PLACE JJ Smith Mojave Desert Ecoregion Loss of Mojave Desert Tortoise Habitat Federally Threatened (listed 1990) Species decline through most of range Red brome, cheatgrass, Mediterranean grasses – poor nutritional value Large, severe fires – habitat loss, spread of annual invasive grasses Habitat restoration identified as highest priority by USFWS Recovery Implementation Teams (RITs). Invasive Annual Grasses and Fuel Continuity Aleta Nafus – BLM Southern Nevada District Lynn Sweet – University of California Riverside • Over 1 million acres burned since 2005 (Mojave Desert Initiative 2010) • 2,307,068 acres burned at least once since 1980 (Mojave Basin and Range REA, NatureServe 2013) Loss of Native Species from Soil Seed Banks Todd C. Esque, James A. Young, C. Richard Tracy. 2010. Short-term effects of experimental fires on a Mojave Desert seed bank. Journal of Arid Environments, 74: 1302-1308. • Fire depleted both native and non-native seed densities • Native seed densities were significantly lower than non-native seed densities both before and after fire National Seed Strategy for Rehabilitation and Restoration ➢ Congress created Native Plant Materials Development Programs in response to catastrophic wildfires in 1998 and 1999 ➢ Builds on 15+ years of work ➢ National Seed Strategy announced August 2015 ➢ Calls for an Unprecedented Level of Collaboration ➢ Developed by the Plant Conservation Alliance (PCA) ➢ Only country in the world with a National Seed Strategy 6 Plant Conservation Alliance Federal Committee 12 Federal Agencies Federal Committee – led by BLM PCA also includes ➢ 325 Non-federal Partners ➢ 9 International Partners 7 National Seed Strategy “The right seed in the right place at the right time.” Goal 1 : Identify seed needs and ensure the reliable availability of genetically appropriate seed. -

Desert-2.Pdf

Desert Contens Top Ten Facts PG 1 front cover 1 All Deserts are all different but they all have low amounts of rain PG 2 contens 2 Deserts normally have less than 40 CM a year 3 The Sahara desert is in Northern Africa and is over 12 different countries PG 3 top ten facts 4 Sahara desert is the largest desert in the Earth PG 4 whether and climate 5 Only around 20% of the Deserts on Earth are covered in sand 6 Around one third of the Earth's surface is covered in Desert PG 5 desert map 7 The largest cold Desert on Earth is Antarctica PG 6 animals and people that live there 8 Located in South America, the Atacama Desert is the driest place in the world PG 7 what grows there 9 Lots of animals live in Deserts such as the wild dog 10 The Arabian Desert in the Middle East is the second largest hot desert on Earth but is substantially smaller than the Sahara. This is a list of the deserts in Wether And Climate the world Arabian Desert. ... Kalahari Desert. ... Wether Mojave Desert. ... Sonoran Desert. ... Chihuahuan Desert. ... This is a map showing Deserts are usually very, very dry. Even the wettest deserts get less than ten Thar Desert. ... the deserts in the world inches of precipitation a year. In most places, rain falls steadily throughout the Gibson Desert. year. But in the desert, there may be only a few periods of rains per year with a lot of time between rains. -

Similarity of Climate Change Data for Antarctica and Nevada

Undergraduate Research Opportunities Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP) Program (UROP) 2010 Aug 3rd, 9:00 AM - 12:00 PM Similarity of climate change data for Antarctica and Nevada Corbin Benally University of Nevada, Las Vegas Shahram Latifi University of Nevada, Las Vegas, [email protected] Karletta Chief Desert Research Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/cs_urop Part of the Climate Commons, and the Desert Ecology Commons Repository Citation Benally, Corbin; Latifi, Shahram; and Chief, Karletta, "Similarity of climate change data for Antarctica and Nevada" (2010). Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP). 5. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/cs_urop/2010/aug3/5 This Event is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Event in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Event has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP) by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Similarity of Climate Change Data for Antarctica and Nevada Corbin Benally1, Dr. Shahram Latifi1, Dr. Karletta Chief2 1University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Las Vegas, NV 2Desert Research Institute, Las Vegas, NV Abstract Results References The correlation between temperature and carbon dioxide Throughout the duration of the research, data was readily 1. -

Gravity Survey of the Western Mojave Desert California

Gravity Survey of the Western Mojave Desert California By DON R. MABEY GEOPHYSICAL FIELD INVESTIGATIONS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 316-D A study of the relation of the gravity anomalies to the geology with special reference to the distribution and thickness of the Cenozoic rocks UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1960 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by^the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C. CONTENTS Page Abstract._____________________________ 51 Gravity anomalies.________________ 5*? Introduction __________________________ 51 Garlock fault zone.____________ Location and cultural features.______ 51 Randsburg-Harper Lake area__-. Purpose of geophysical investigations. 52 Boron-Kramer Junction area___. 64 Acknowledgments__ ______________ 64: 53 Barstow-Cajon Pass area. ______ 6" Physical and geologic features.__________ 53 Antelope Valley area___________ Physiography and drainage.________ 53 Significance of the gravity anomalies. 6° Geology __________________________ 53 Geologic significance___________ 6^ Gravity survey._______________________ 55 Economic significance____._-__. 7? Fieldwork and reduction of data-____ 55 Conclusions. ___ ___________________ 71 Bouguer anomaly map.____________ 56 Selected references.________________ 71 Problems of interpretation._________ 56 Index_ ___________________________ 7? ILLUSTRATIONS [Plates are in pocket] PLATE 10. Bouguer anomaly and generalized geologic map of the western Mojave Desert. 11. Bouguer anomaly and generalized geologic map of the area in the vicinity of the Kramer borate district. 12. Map showing major gravity trends, faults, and inferred faults in the western Mojave Desert. Pag-? FIQUKE 22. Index map of southern California showing area of this report in relation to the Mojave Desert and other physiographic features_______________-___________________________-___-_-_---_-------_-_-__-____ 52 23. -

World Deserts

HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY World Deserts Reader Frog in the Australian Outback Joshua tree in the Mojave Desert South American sheepherder Camel train across the Sahara Desert THIS BOOK IS THE PROPERTY OF: STATE Book No. PROVINCE Enter information COUNTY in spaces to the left as PARISH instructed. SCHOOL DISTRICT OTHER CONDITION Year ISSUED TO Used ISSUED RETURNED PUPILS to whom this textbook is issued must not write on any page or mark any part of it in any way, consumable textbooks excepted. 1. Teachers should see that the pupil’s name is clearly written in ink in the spaces above in every book issued. 2. The following terms should be used in recording the condition of the book: New; Good; Fair; Poor; Bad. World Deserts Reader Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You are free: to Share—to copy, distribute, and transmit the work to Remix—to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution—You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation (www.coreknowledge.org) made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial—You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike—If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. -

Paleomagnetism and Tectonic Rotation of the Lower Miocene Peach Springs Tuff: Colorado Plateau, Arizona, to Barstow, California

Paleomagnetism and tectonic rotation of the lower Miocene Peach Springs Tuff: Colorado Plateau, Arizona, to Barstow, California JQHNEWWH[LLHOUSE i V-S-Geological Survey, Menlo Park, California 94025 ABSTRACT detachment unexpectedly show no significant rotation. From this rela- tion, we infer that rotations are accommodated along numerous low- We have determined remanent magnetization directions of the angle faults at higher structural levels above the detachment surface. lower Miocene Peach Springs Tuff at 41 localities in western Arizona and southeastern California. An unusual northeast and shallow mag- INTRODUCTION netization direction confirms the proposed geologic correlation of iso- lated outcrops of the tuff from the Colorado Plateau to Barstow, Remnants of block-faulted and tilted middle Tertiary volcanic and California, a distance of 350 km. The Peach Springs Tuff was appar- sedimentary sequences are exposed in numerous mountain ranges extend- ently emplaced as a single cooling unit about 18 or 19 Ma and is now ing westward from the Colorado Plateau of Arizona into the central exposed in 4 tectonic provinces west of the Plateau, including the Mojave Desert of southeastern California (Fig. la). Exposed in many of Transition Zone, Basin and Range, Colorado River extensional corri- these isolated Tertiary sections, there is a distinctive, lower Miocene ash- dor, and central Mojave Desert strike-slip zone. As such, the tuff is an flow tuff which Glazner and others (1986) correlated with the Peach ideal stratigraphic and structural marker for paleomagnetic assess- Springs Tuff of western Arizona (Fig. lb). The Peach Springs Tuff was ment of regional variations in tectonic rotations about vertical axes. -

Deserts Province

Province-Specific Conservation Strategies – Deserts 5.6 Deserts Province 5.6.1 Geophysical and Ecological Description of the Province The Deserts Province extends from the California-Mexico border on the south and Colorado River on the southeast north to Topaz Lake on the California-Nevada border (Figure 5.6-1). The province’s western border is formed by the Peninsula Mountain Ranges and Transverse Mountain Range in southern California, and the Sierra Nevada in central California. The province is the extension of desert regions located to the east and south of California in the states of Nevada and Arizona, and in Mexico. The Deserts Province has five different subregions: from north to south these are the Mono subregion, the Southeastern Great Basin, Mojave Desert, Sonoran Desert, and Colorado Desert. Each subregion has unique combinations of climate, topography, ecology, and land-use patterns. The province as a whole is in the rain shadow of mountain ranges that form the western border. The dry landscape created by this barrier is characterized by unique geologic features composed of cliffs, peaks, canyons, dry washes, sand dunes, and large dry lake playas. Elevations are generally low in the southern portion of the province and rise to the north. The elevation in the south (Sonoran and Colorado deserts subregion) is generally below 1,000 feet with the lowest point at 275 feet below sea level in the Salton Trough. The topography of the more northerly portion of the province (Mojave Desert subregion) is characterized by a moderately high plateau: elevations range from 282 feet below sea level in Death Valley to 11,000 feet above sea level in the Panamint Mountains.