The Origin and Meaning of the Name “Manhattan” Ives Goddard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Principal Indian Towns of Western Pennsylvania C

The Principal Indian Towns of Western Pennsylvania C. Hale Sipe One cannot travel far in Western Pennsylvania with- out passing the sites of Indian towns, Delaware, Shawnee and Seneca mostly, or being reminded of the Pennsylvania Indians by the beautiful names they gave to the mountains, streams and valleys where they roamed. In a future paper the writer will set forth the meaning of the names which the Indians gave to the mountains, valleys and streams of Western Pennsylvania; but the present paper is con- fined to a brief description of the principal Indian towns in the western part of the state. The writer has arranged these Indian towns in alphabetical order, as follows: Allaquippa's Town* This town, named for the Seneca, Queen Allaquippa, stood at the mouth of Chartier's Creek, where McKees Rocks now stands. In the Pennsylvania, Colonial Records, this stream is sometimes called "Allaquippa's River". The name "Allaquippa" means, as nearly as can be determined, "a hat", being likely a corruption of "alloquepi". This In- dian "Queen", who was visited by such noted characters as Conrad Weiser, Celoron and George Washington, had var- ious residences in the vicinity of the "Forks of the Ohio". In fact, there is good reason for thinking that at one time she lived right at the "Forks". When Washington met her while returning from his mission to the French, she was living where McKeesport now stands, having moved up from the Ohio to get farther away from the French. After Washington's surrender at Fort Necessity, July 4th, 1754, she and the other Indian inhabitants of the Ohio Val- ley friendly to the English, were taken to Aughwick, now Shirleysburg, where they were fed by the Colonial Author- ities of Pennsylvania. -

In Search of the Indiana Lenape

IN SEARCH OF THE INDIANA LENAPE: A PREDICTIVE SUMMARY OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT OF THE LENAPE LIVING ALONG THE WHITE RIVER IN INDIANA FROM 1790 - 1821 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY JESSICA L. YANN DR. RONALD HICKS, CHAIR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2009 Table of Contents Figures and Tables ........................................................................................................................ iii Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 Research Goals ............................................................................................................................ 1 Background .................................................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 2: Theory and Methods ................................................................................................. 6 Explaining Contact and Its Material Remains ............................................................................. 6 Predicting the Intensity of Change and its Effects on Identity................................................... 14 Change and the Lenape .............................................................................................................. 16 Methods .................................................................................................................................... -

Bxm6 Bus Schedule

Bus Timetable Effective Spring 2019 MTA Bus Company BxM6 Express Service Between Parkchester, Bronx, and Midtown, Manhattan If you think your bus operator deserves an Apple Award — our special recognition for service, courtesy and professionalism — call 511 and give us the badge or bus number. Fares – MetroCard® is accepted for all MTA New York City trains (including Staten Island Railway - SIR), and, local, Limited-Stop and +SelectBusService buses (at MetroCard fare collection machines). Express buses only accept 7-Day Express Bus Plus MetroCard or Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard. All of our buses and +SelectBusService Coin Fare Collector machines accept exact fare in coins. Dollar bills, pennies, and half-dollar coins are not accepted. Free Transfers – Unlimited Ride Express Bus Plus MetroCard allows free transfers between express buses, local buses and subways, including SIR, while Unlimited Ride MetroCard permits free transfers to all but express buses. Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard allows one free transfer of equal or lesser value (between subway and local bus and local bus to local bus, etc.) if you complete your transfer within two hours of paying your full fare with the same MetroCard. If you transfer from a local bus or subway to an express bus you must pay an additional $3.75 from that same MetroCard. You may transfer free from an express bus, to a local bus, to the subway, or to another express bus if you use the same MetroCard. If you pay your local bus fare in coins, you can request a transfer good only on another local bus. Reduced-Fare Benefits – You are eligible for reduced-fare benefits if you are at least 65 years of age or have a qualifying disability. -

Tickets and Fares

New York Fares Connecticut Fares Effective January 1, 2013 New York State Stations/ Zones Fares to GCT/ Harlem-125th Street Sample fares to GCT/ Harlem-125th Street Select Intermediate Fares to Greenwich On-board fares are indicated in red. On-board fares are indicated in red. On-board fares are indicated in red. 10-Trip One-Way Monthly Weekly 10-Trip 10-Trip One -Way One -Way 10-Trip One-Way Destination Monthly Weekly 10-Trip Zone Harlem Line Hudson Line Zone Senior/ Senior/ Stations Monthly Weekly 10-Trip 10-Trip Senior/ One -Way One -Way Senior/ Commutation Commutation Peak Off -Peak Disabled/ Peak Off -Peak Disabled/ Commutation Commutation Peak Off -Peak Disabled/ Peak Off -Peak Disabled/ Origin Station(s) Station Commutation Commutation Intermediate One-Way Medicare Medicare Medicare Medicare $6.75 $5.00 $3.25 1 Harlem -125th Street Harlem -125th Street 1 $154.00 $49.25 $67.50 $42.50 $32.50 Greenwich INTRASTATE CONNECTICUT $13.00 $11.00 $3.25 Melrose Yankees-E. 153rd Street Cos Cob $12.00 $9.00 $6.00 $2.50 $263.00 $84.25 $120.00 $76.50 $60.00 Stamford thru Rowayton Greenwich $55.50 $17.25 $21.25 Tremont Morris Heights $7.50 $5.75 $3.75 Riverside $18.00 $15.00 $6.00 $9.00 2 $178.00 $55.50 $75.00 $49.00 $37.50 Old Greenwich Tickets Fordham University Heights $14.00 $12.00 $3.75 $2.50 Glenbrook thru New Canaan Greenwich $55.50 $17.25 $21.25 Botanical Garden Marble Hill 2 $9.25 $7.00 $4.50 $9.00 Williams Bridge Spuyten Duyvil 3 $204.00 $65.25 $92.50 $59.50 $45.00 Stamford $15.00 $13.00 $4.50 $3.25 Woodlawn Riverdale Noroton Heights -

A-Brief-History-Of-The-Mohican-Nation

wig d r r ksc i i caln sr v a ar ; ny s' k , a u A Evict t:k A Mitfsorgo 4 oiwcan V 5to cLk rid;Mc-u n,5 3 ss l Y gew y » w a. 3 k lz x OWE u, 9g z ca , Z 1 9 A J i NEI x i c x Rat 44MMA Y t6 manY 1 YryS y Y s 4 INK S W6 a r sue`+ r1i 3 My personal thanks gc'lo thc, f'al ca ° iaag, t(")mcilal a r of the Stockbridge-IMtarasee historical C;orrunittee for their comments and suggestions to iatataraare tlac=laistcatic: aal aac c aracy of this brief' history of our people ta°a Raa la€' t "din as for her c<arefaal editing of this text to Jeff vcic.'of, the rlohican ?'yews, otar nation s newspaper 0 to Chad Miller c d tlac" Land Resource aM anaagenient Office for preparing the map Dorothy Davids, Chair Stockbridge -Munsee Historical Committee Tke Muk-con-oLke-ne- rfie People of the Waters that Are Never Still have a rich and illustrious history which has been retrained through oral tradition and the written word, Our many moves frorn the East to Wisconsin left Many Trails to retrace in search of our history. Maanv'rrails is air original design created and designed by Edwin Martin, a Mohican Indian, symbol- izing endurance, strength and hope. From a long suffering proud and deternuned people. e' aw rtaftv f h s is an aatathCutic basket painting by Stockbridge Mohican/ basket weavers. -

Hudson Valley Community College

A.VII.4 Articulation Agreement: Hudson Valley Community College (HVCC) to College of Staten Island (CSI) Associate in Science in Business Administration (HVCC) to Bachelor of Science: International Business Concentration (CSI) THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ARTICULATION AGREEMENT BETWEEN HUDSON VALLEY COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND COLLEGE OF STATEN ISLAND A. SENDING AND RECEIVING INSTITUTIONS Sending Institution: Hudson Valley Community College Department: Program: School of Business and Liberal Arts Business Administration Degree: Associate in Science (AS) Receiving Institution: College of Staten Island Department: Program: Lucille and Jay Chazanoff School of Business Business: International Business Concentration Degree: Bachelor of Science (BS) B. ADMISSION REQUIREMENTS FOR SENIOR COLLEGE PROGRAM Minimum GPA- 2.5 To gain admission to the College of Staten Island, students must be skill certified, meaning: • Have earned a grade of 'C' or better in a credit-bearing mathematics course of at least 3 credits • Have earned a grade of 'C' or better in freshmen composition, its equivalent, or a higher-level English course Total transfer credits granted toward the baccalaureate degree: 63-64 credits Total additional credits required at the senior college to complete baccalaureate degree: 56-57 credits 1 C. COURSE-TO-COURSE EQUIVALENCIES AND TRANSFER CREDIT AWARDED HUDSON VALLEY COMMUNITY COLLEGE COLLEGE OF STATEN ISLAND Credits Course Number & Title Credits Course Number & Title Credits Awarded CORE RE9 UIREM EN TS: ACTG 110 Financial Accounting 4 -

Newark Earthworks Center - Ohio State University and World Heritage - Ohio Executive Committee INDIANS and EARTHWORKS THROUGH the AGES “We Are All Related”

Welcoming the Tribes Back to Their Ancestral Lands Marti L. Chaatsmith, Comanche/Choctaw Newark Earthworks Center - Ohio State University and World Heritage - Ohio Executive Committee INDIANS AND EARTHWORKS THROUGH THE AGES “We are all related” Mann 2009 “We are all related” Earthen architecture and mound building was evident throughout the eastern third of North America for millennia. Everyone who lived in the woodlands prior to Removal knew about earthworks, if they weren’t building them. The beautiful, enormous, geometric precision of the Hopewell earthworks were the culmination of the combined brilliance of cultures in the Eastern Woodlands across time and distance. Has this traditional indigenous knowledge persisted in the cultural traditions of contemporary American Indian cultures today? Mann 2009 Each dot represents Indigenous architecture and cultural sites, most built before 1491 Miamisburg Mound is the largest conical burial mound in the USA, built on top of a 100’ bluff, it had a circumference of 830’ People of the Adena Culture built it between 2,800 and 1,800 years ago. 6 Miamisburg, Ohio (Montgomery County) Picture: Copyright: Tom Law, Pangea-Productions. http://pangea-productions.net/ Items found in mounds and trade networks active 2,000 years ago. years 2,000 active networks trade and indicate vast travel Courtesy of CERHAS, Ancient Ohio Trail Inside the 50-acre Octagon at Sunrise 8 11/1/2018 Octagon Earthworks, Newark, OH Indigenous people planned, designed and built the Newark Earthworks (ca. 2000 BCE) to cover an area of 4 square miles (survey map created by Whittlesey, Squier, and Davis, 1837-47) Photo Courtesy of Dan Campbell 10 11/1/2018 Two professors recover tribal knowledge 2,000 years ago, Indigenous people developed specialized knowledge to construct the Octagon Earthworks to observe the complete moon cycle: 8 alignments over a period of 18 years and 219 days (18.6 years) “Geometry and Astronomy in Prehistoric Ohio” Ray Hively and Robert Horn, 1982 Archaeoastronomy (Supplement to Vol. -

A Lenape Among the Quakers

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters University of Nebraska Press 2014 A Lenape among the Quakers Dawn G. Marsh [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples Marsh, Dawn G., "A Lenape among the Quakers" (2014). University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters. 266. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples/266 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Nebraska Press at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A Lenape among the Quakers Buy the Book Buy the Book A Lenape among the Quakers The Life of Hannah Freeman dawn g. marsh University of Nebraska Press Lincoln & London Buy the Book © 2014 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska Parts of this book have previously appeared in different form in “Hannah Freeman: Gendered Sovereignty in Penn’s Peaceable Kingdom,” in Gender and Sovereignty in Indigenous North America, 1400–1850, ed. Sandra Slater and Fay A. Yarborough (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2011), 102–22. All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Marsh, Dawn G. A Lenape among the Quakers: the life of Hannah Freeman / Dawn G. Marsh. pages cm. Includes bibliographical references. isbn 978-0-8032-4840-3 (cloth: alk. paper)— isbn 978-0-8032-5419-0 (epub)— isbn 978-0-8032-5420-6 (mobi)— isbn 978-0-8032-5418-3 (pdf) 1. -

Fabrics and Typologies: New York / Global Supplemental

Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture Planning and Preservation A6837 Urban Design Seminar IIA Richard Plunz, Instructor Fall 2016 FABRICS AND TYPOLOGIES: NEW YORK / GLOBAL SUPPLEMENTAL READINGS Part I: Lectures on New York City Richard Plunz, Instructor Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation Fall 2016 A6837 FABRICS AND TYPOLOGIES: NEW YORK/GLOBAL Instructor: Richard Plunz _______________________________________________________________________________________ READINGS FOR PART I LECTURES:* *In addition to assigned readings in A History of Housing in New York City. Lecture 1: ORIGINS: LOCAL FABRICS / GLOBAL TYPOLOGIES Enrico Guidoni, “Street and Block from the Late Middle Ages to the Eighteenth Century,” Lotus 19 (1978). Pp. 5-19. Giulio Carlo Argan, “On the Typology of Architecture,” Architectural Design 33 (December 1963). pp. 564-565. Rafael Moneo, “On Typology,” Oppositions 13 (Summer 1978). Pp. 23-45. Jean Castex and Philippe Panerai, “Prospects for Typomorphology,” Lotus 36 (1982), pp. 94-99. Christel Hollevoet, “Wandering in the City. Flânerie to Dérive and After: The Cognitive Mapping of Urban Space ,” in Hollevoet and Karen Jones , The Power of the City. The City of Power New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1992. pp. 25-56. Stephen Barber, Fragments of the European City London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 1995. pp. 67- 76; 91-107. Lieven DeCauter, “The City in the Age of Transcendental Capitalism,” in Decauter, The Capsular Civilization Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 2004. Pp. 40-53. Lecture 2: TERRACE URBANISM AND ITS DERIVITIVES, 1628-1863 "Geology," in John Kieran, A Natural History of New York City. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1959. Ch. 2. "The Lenape," in Eric W. Sanderson, Mannahatta. -

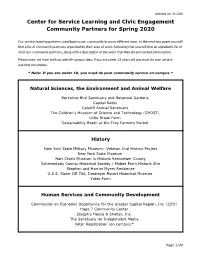

Center for Service Learning and Civic Engagement Community Partners for Spring 2020

Updated Jan 16 2020 Center for Service Learning and Civic Engagement Community Partners for Spring 2020 Our service learning partners contribute to our community in many different ways. In the next two pages you will find a list of community partners organized by their area of work. Following that you will find an alphabetic list of all of our community partners, along with a description of the work that they do and contact information. Please note, we have both on and off-campus sites. If you are under 18 years old you must do your service learning on campus. * Note: If you are under 18, you must do your community service on-campus * Natural Sciences, the Environment and Animal Welfare Berkshire Bird Sanctuary and Botanical Gardens Capital Roots Catskill Animal Sanctuary The Children’s Museum of Science and Technology (CMOST) Little Brook Farm Sustainability Booth at the Troy Farmers Market History New York State Military Museum– Veteran Oral History Project New York State Museum Hart Cluett Museum in Historic Rensselaer County Schenectady County Historical Society / Mabee Farm Historic Site Stephen and Harriet Myers Residence U.S.S. Slater DE 766, Destroyer Escort Historical Museum Yates Farm Human Services and Community Development Commission on Economic Opportunity for the Greater Capital Region, Inc. (CEO) Hope 7 Community Center Joseph’s House & Shelter, Inc. The Sanctuary for Independent Media Voter Registration (on campus)* Page 1/20 Updated Jan 16 2020 Literacy and adult education English Conversation Partners Program (on campus)* Learning Assistance Center (on campus)* Literacy Volunteers of Rensselaer County The RED Bookshelf Daycare, school and after-school programs, children’s activities Albany Free School Albany Police Athletic League (PAL), Inc. -

ANISHINABEG CULTURE.Pdf

TEACHER RESOURCE LESSON PLAN EXPLORING ANISHINABEG CULTURE MI GLCES – GRADE THREE SOCIAL STUDIES H3 – History of Michigan Through Statehood • 3-H3.0.1 - Identify questions historians ask in examining Michigan. • 3-H3.0.5 - Use informational text and visual data to compare how American Indians and settlers in the early history of Michigan adapted to, used, and modifi ed their environment. • 3-H3.0.6 - Use a variety of sources to describe INTRODUCTION interactions that occured between American Indians and the fi rst European explorers and This lesson helps third grade students understand settlers of Michigan. the life and culture of the Native Americans that G5 - Environment and Society lived in Michigan before the arrival of European settlers in the late 17th century. It includes • 3-G5.0.2 - Decribe how people adapt to, use, a comprehensive background essay on the and modify the natural resources of Michigan. Anishinabeg. The lesson plan includes a list of additional resources and copies of worksheets and COMMON CORE ANCHOR STANDARDS - ELA primary sources needed for the lessons. Reading • 1 - Read closely to determine what the text says ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS explicitly and to make logical inferences from it. What are key cultural traits of the Native Americans • 7 - Intergrate and evaluate content presented who lived in Michigan before the arrival of in diverse media and formats, including visually Europeans? and quantitatively, as well as in words. Speaking and Listening LEARNING OBJECTIVES • 2 - Integrate and evaluate information presented Students will: in diverse media and formats, including visually, • Learn what Native American groups traveled quantitatively, and orally. -

Folk Taxonomy, Nomenclature, Medicinal and Other Uses, Folklore, and Nature Conservation Viktor Ulicsni1* , Ingvar Svanberg2 and Zsolt Molnár3

Ulicsni et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2016) 12:47 DOI 10.1186/s13002-016-0118-7 RESEARCH Open Access Folk knowledge of invertebrates in Central Europe - folk taxonomy, nomenclature, medicinal and other uses, folklore, and nature conservation Viktor Ulicsni1* , Ingvar Svanberg2 and Zsolt Molnár3 Abstract Background: There is scarce information about European folk knowledge of wild invertebrate fauna. We have documented such folk knowledge in three regions, in Romania, Slovakia and Croatia. We provide a list of folk taxa, and discuss folk biological classification and nomenclature, salient features, uses, related proverbs and sayings, and conservation. Methods: We collected data among Hungarian-speaking people practising small-scale, traditional agriculture. We studied “all” invertebrate species (species groups) potentially occurring in the vicinity of the settlements. We used photos, held semi-structured interviews, and conducted picture sorting. Results: We documented 208 invertebrate folk taxa. Many species were known which have, to our knowledge, no economic significance. 36 % of the species were known to at least half of the informants. Knowledge reliability was high, although informants were sometimes prone to exaggeration. 93 % of folk taxa had their own individual names, and 90 % of the taxa were embedded in the folk taxonomy. Twenty four species were of direct use to humans (4 medicinal, 5 consumed, 11 as bait, 2 as playthings). Completely new was the discovery that the honey stomachs of black-coloured carpenter bees (Xylocopa violacea, X. valga)were consumed. 30 taxa were associated with a proverb or used for weather forecasting, or predicting harvests. Conscious ideas about conserving invertebrates only occurred with a few taxa, but informants would generally refrain from harming firebugs (Pyrrhocoris apterus), field crickets (Gryllus campestris) and most butterflies.