Audience Development and Local History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Benefice of Pickering with Levisham, Lockton and Marishes

The Benefice of Pickering with Levisham, Lockton and Marishes We pray for a Priest to lead us. If you think you may be that person, please read our Benefice profile below We are able to offer: a committed, worshipful, predominantly mature congregation with a steady attendance of approximately 100 people at services every Sunday. broad churchmanship with liberal catholic character reverent observance of services during Holy Week and other Feast days throughout the Church’s year by a good number of the congregation an active Ministry team of retired clergy Lay involvement during the services, e.g. altar servers, intercessors, eucharistic ministers a desire to minister throughout the community four well maintained churches a Walsingham cell and annual pilgrimage of approximately 25 members of the congregation to the Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham in north Norfolk good ecumenical relations with other local Churches an award-winning team of bellringers a strong musical focus provided by our organist and choir an area strong on tourism and world-famous wall paintings We are seeking a priest that God has prepared for us who will find warm and strong support from committed people within the congregations. a priest who is from the central tradition of the church, faithful in the Ministry of the Word and Sacrament a priest with vision, excellent preaching skills, who will be able to build on our strong foundations whilst working to develop healthy, growing churches which are well- equipped to take the gospel out into the wider community a caring individual with a zeal for the pastoral care for members of the Church and wider community. -

Newton-On-Rawcliffe

10/10/2017 Dales Trails |Home | Calendar | Trans-Dales Trail 1 | Trans-Dales Trail 2 | Trans-Dales Trail 3 | Go walking with Underwood | Dales Trails NORTH YORK MOORS : Newton-on-Rawcliffe Newton Dale - 14.4km (9 miles) Newton Dale is one of the most spectacular valleys in the north of England, created when melt water from an ice age glacier gouged a deep gorge through the hills. Newton Dale’s forest & moorland, ups & downs, streams & steam trains together make this a classic walk on the North York Moors. Fact File Distance 14.4km (9 miles) Time 4 hours Map OS Explorer OL27 North York Moors (East) Start/Parking Newton-on-Rawcliffe (near the pond) Forest and moorland paths & tracks – two steep Terrain descents and ascents Grading **** nearest Town Pickering Black Swan Inn at Newton-on-Rawcliffe and Refreshments refreshment kiosk at Levisham station (when trains running) Toilets Levisham station Moorsbus (M6/M8 Pickering – Rosedale) operates via Public Newton-on-Rawcliffe (Sundays – March to Oct, also Transport Wednesdays July - Sept) Stiles 6 http://www.dalestrails.co.uk/Newton-on-Rawcliffe.htm 1/4 10/10/2017 Dales Trails Route created using TrackLogs Digital Mapping Image reproduced with kind permission of Ordnance Survey and Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland. 1. (Start) Walk due north from the pond up the road past the village hall towards a bend and a junction with two lanes on the right. Take the bridleway heading straight ahead (north) which drops downhill passing a cattle-shed. Newton Bank falls steeply on the right into Newton Dale. The track swings left and drops down to cross a stream at Raygate Slack. -

Officers of the Society 1970-71

CONTENTS PAGE Frontispiece: Professor David Winton Thomas .. .. 4 Officers of the Society .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 News of the Society Notices and Reports .. .. .. .. .. 6-9 A Personal Note .. .. .. .. .. 9 St Catharine's Gild 10 The Society's Finances .. .. .. .. .. 11 The General Meeting of the Society, 1970 .. .. 12-13 The Quincentenary Appeal Accounts .. .. .. 14 The Quincentenary Accounts .. .. .. .. 15 The Annual Dinner, 1970 16-17 Engagements .. .. .. .. .. .. 18 Marriages .. .. .. .. .. .. 18-19 Births 19-20 Deaths 21 Obituaries 22-27 Ecclesiastical Appointments .. .. .. .. 28 Miscellaneous .. .. .. .. .. .. 29-36 Publications 37-39 News of the College College News Letter 40-43 The College Societies 44-50 Academic Distinctions .. .. .. .. .. 51-52 Articles The World of Music .. 53-54 ' Let us now praise famous men ' .. .. .. 54-55 Illustrations Interlude .. .. .. .. .. .. (facing) 10 Degree Day 1970 40 Another Year Ends .. .. .. .. .. 44 Professor David Winton Thomas Fellow of St Catharine's 1943-1969 SEPTEMBER 1970 Officers of the Society 1970-71 President Sydney Smith, PH.D., M.A. Vice-Presidents C. R. Allison, M.A. R. T. Pemberton C. Belfield Clarke, M.A. D. Portway, C.B.E., T.D., D.L., M.A. C. R. Benstead, M.C, M.A. The Reverend F. E. Smith, M.A. Sir Frank Bower, C.B.E., M.A. A. Stephenson, M.A. R. F. Champness, M.A., LL.M. A. H. Thomas, LL.D., M.A. R. Davies, C.M.G., M.A. Sir Augustus Walker, K.C.B., Sir Norman Elliott, C.B.E., M.A. C.B.E., D.S.O., D.F.C, M.A. A. A. Heath, M.A. E. Williamson, M.A. -

North Yorkshire Hole of Horcum

NORTH YORKSHIRE GLAMORGAN 19 HOLE OF HORCUM 20 MERTHYR MAWR WALES uDistance: 7½ miles/12km uTime: 4½ hours uGrade: Moderate EAST NORTH uDistance: 5¾ miles/9km uTime: 3 hours uGrade: Moderate Descending Saltergate Bank PLAN YOUR WALK Afon Ogwr and PLAN YOUR WALK into the Hole of Horcum. the salt marshes. FEATURE SEE ON PAGE 42 PHOTO: PHOTO: TOM BAILEY TOM ROUTE JULIE ROYLE ROUTE Start/parking Roadside Start/parking Beach Road, parking in Levisham, YO18 Newton, Porthcawl, grid 7NL, grid ref SE833905 ref SS836769 Is it for me? Mostly clear Is it for me? Sandy beach, paths across moorland dunes, scrub, woodland, CHOSEN BY… Inn and follow Braygate Lane. and through river valleys; CHOSEN BY… wonderful examples of the grassland, heath, marsh NICK HALLISSEY Where road bends L, continue boggy patches after rain JULIE ROYLE other habitats encompassed Stiles 2 This classic North ahead on enclosed track (still Stiles 1 Merthyr Mawr by this incredibly varied nature York Moors route marked as Braygate Lane on Warren National reserve. There are complex PLANNING PLANNING presents the Hole of Horcum OS Explorer map). On reaching Nature Reserve is relatively woodlands which have Nearest town Porthcawl Nearest town Pickering Refreshments The Jolly as it should be seen – as a gate, go through (or cross stile) little known, yet it is one of developed entirely within Refreshments Horseshoe Sailor and the Ancient surprise from Saltergate Bank, and continue ahead onto Inn in Levisham at start the wonders of Wales. It has hollows between dunes, areas Briton at Newton before diving headlong into open moorland, keeping wall L. -

Walkslevisham,Skelton Towerandnewtondale

Walks 11 what’son Schematic Walks Levisham, Skelton map – take OS Explorer OL27 with you Tower and Newton Dale Walk Information out over 10,000 years ago by great walk along the road away from the torrents of water thundering station and over a cattle grid, just down this once small valley. This beyond which (as the road climbs Distance: 7.25 km (4.5 miles) is known as a “misfit” valley as up) take the path to the right Time: Allow 2 – 3 hours the tiny stream of Pickering Beck immediately after the house on Map: OS Explorer Sheet OL27 is obviously too small to have the right (signpost Levisham), Start/Parking: Levisham station created such a vast valley by itself over a stream and through a gate or village. – it had to have had help by into woodland. A clear path leads Refreshments: Horseshoe Inn, melting glaciers. up through woods to reach a gate Levisham that brings you out on the open Terrain: Clear moorland and Threading its way along the floor hillside then head straight uphill, woodland paths and tracks almost of this valley is the North bearing slightly to the right, to all the way, with a number of Yorkshire Moors Railway. This reach a stile next to a gate that steep inclines. historic line was completed in 1836 leads onto a grassy track. Turn Steam Railway: Why not start and between Pickering with Whitby, right along the track then almost finish this walk in style aboard a built to provide a stimulus for its immediately head up the wide, steam train on the North flagging whaling and shipbuilding grassy path that branches up to Yorkshire Moors Railway. -

Levisham Moor and the Hole of Horcum

Levisham Moor and the Hole of Horcum Hole of Horcum The Hole of Horcum is one of the most spectacular features in the National Park – a huge natural amphitheatre 400 feet deep and more than half a mile across. Legends hang easily upon a place known as the ‘Devil’s Punchbowl’ – the best-known says that it was formed when Wade the Giant scooped up a handful of earth to throw at his wife during an argument. Actually, it was created by a process called spring-sapping, whereby water welling up from the hillside has gradually undermined the slopes above, eating the rocks ral wonders and an nts away grain by grain. Over thousands of years, a once narrow valley has widened and natu cient monume deepened into an enormous cauldron – and the process still continues today. Mike Kipling e prepared for grand landscapes and big views on this North York Moors Bclassic. Starting with the dramatic panorama from Saltergate over the Hole Levisham Moor of Horcum, the 5-mile scenic walk follows a prominent track over Levisham The track across Levisham Moor runs through a landscape Moor, past important archaeological remains. There’s a possible diversion rich in archaeological remains – in fact the moor itself is to the stunning viewpoint of Skelton Tower, after which the route drops into the largest ancient monument in the North York Moors. the rocky ravine of Dundale Griff and returns along the valley to the Hole of Half-hidden in the heather are traces of human occupation Horcum, climbing back out at Saltergate. -

NYM-Landscape-Character-Assessment-Reduced.Pdf

WHITE YOUNG GREEN ENVIRONMENTAL NORTH YORK MOORS NATIONAL PARK LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT CONTENTS Page No 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background to the Report 1 1.2 The North York Moors National Park 1 1.3 Context and Scope of the Study 1 1.4 The Study Area 2 1.5 Relationship to Previous Studies 2 1.6 Relationship to Studies Undertaken within Areas Bounding the National Park 5 1.7 Methodology 6 1.8 Structure of the Report 7 1.9 The Next Steps 7 2.0 THE NORTH YORK MOORS NATIONAL PARK 8 2.1 Key Characteristics 8 2.2 Landscape Character 8 2.3 Physical Influences 9 2.4 Historical and Cultural Influences 10 2.5 Buildings and Settlement 11 2.6 Land Cover 11 3.0 CHANGE IN THE LANDSCAPE 13 3.1 Introduction 13 3.2 Agriculture 13 3.3 Upland Management 15 3.4 Biodiversity Aims 15 3.5 Trees, Woodland and Commercial Forestry 16 3.6 Recreation and Tourism 17 3.7 Settlement Change and Expansion 18 3.8 Communications, Power Generation and Distribution, Military Infrastructure 18 3.9 Roads and Traffic 19 3.10 Mining and Quarries 20 3.11 External Influences 20 3.12 Air Pollution and Climate Change 20 3.13 Geological and Archaeological Resource 20 4.0 LANDSCAPE CHARACTER TYPES AND AREAS 22 Moorland 23 (1a) Western Moors 26 (1b) Central & Eastern Moors 27 (1c) Northern Moors 29 Narrow Moorland Dale 34 (2a) Ryedale 37 (2b) Bilsdale 38 (2c) Bransdale 39 (2d) Farndale 40 (2e) Rosedale 41 (2f) Hartoft 42 (2g) Baysdale 42 (2h) Westerdale 43 (2i) Danby Dale 43 North York Moors National Park Authority North York Moors National Park Landscape Character Assessment -

North York Moors National Park Authority Business Plan 2017-2020

North York Moors National Park Authority Business Plan 2017-2020 North York Moors National Park Authority Business Plan 2017-20 Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 PRIORITIES, RESOURCES AND PERFORMANCE ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 MEDIUM TERM FINANCIAL STRATEGY ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 EXTERNAL FUNDING PRIORITIES ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 OBJECTIVES AND TARGETS .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 11 ENVIRONMENT .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

INVASIVE NON-NATIVE SPECIES REPORT and CONTROL STRATEGY for Riparian Plants

INVASIVE NON-NATIVE SPECIES REPORT and CONTROL STRATEGY for Riparian plants YORKSHIRE DERWENT CATCHMENT November 2019 Original Author: Matt Cross 2017 Revised by Vanessa Barlow 2019 Yorkshire Wildlife Trust 1 St. George’s Place York YO24 1GN Tel: 01904 659570 Email: [email protected] www.ywt.org.uk Yorkshire Wildlife Trust is a company limited by guarantee, registered in England Number 409650 Registered Charity Number 210807 ©Yorkshire Wildlife Trust 2019 All rights reserved INNS Report and Control Strategy Table of Contents Overview of work 2019/20 .................................................................................................................... 5 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 1.1 The Yorkshire Derwent Catchment ................................................................................................. 5 1.2 River Derwent SSSI .......................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Invasive Non-Native Species (INNS) ................................................................................................ 6 1.3.1 INNS Legislation ........................................................................................................................ 7 2 INNS status in the Yorkshire Derwent Catchment ......................................................................... 9 3 Determining Priorities .............................................................................................................. -

Gridline 2016 Spring

GRIDLINESpring 2016 The magazine for landowners Remote antidote How a hut in the wilderness is making dreams come true The City artisans The Square Mile’s not-so-secret craft society Callsunshine me mister Inside Meet the man with spring in his step on a mission to brighten up The town using nature to our homes all year round fight back against the floods How important is it to stay in touch? WIN a two-night getaway of your choice 00945_Gridline_Cover_v2.indd 2 04/03/2016 09:58 16 Some useful contact numbers The Land & Business Support team are responsible for acquiring all rights and permissions from statutory authorities and landowners needed to install, operate and maintain National Grid’s electricity and gas transmission networks. The group acts as the main interface for landowners who have gas and electricity equipment installed on their land. Your local contacts are listed below. ELECTRICITY AND GAS » Land teams – all regions 0800 389 5113 WAYLEAVE PAYMENTS » For information on wayleave payments, telephone the payments helpline on 0800 389 5113 CHANGE OF DETAILS » To inform National Grid of changes in ownership or contact details, telephone 0800 389 5113 for electric and 01926 654844 for gas, or email [email protected] ELECTRICITY EMERGENCY » Emergency calls to report pylon damage to National Grid can be made on 0800 404090. Note the tower’s number – found just below the property plate – to help crews locate it ELECTRIC AND MAGNETIC FIELDS 10 Many grantors have » For information on electric and magnetic fields, worked hard against call the EMF information line on 08457 023270 the odds and the (local call rate). -

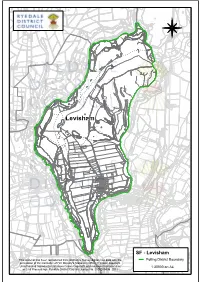

Levisham.Pdf

Cropton Forest CS A 169 Stone Wilden Moor Rotten Gill Black Rigg Pickering Moor Def Track ED & Ward Bdy SS Yaul Sike Slack Hussacks Def Sheepfold Yaul Sike N Slack Def Needle Point Saltergate Moor FB Track CS Path (um) Havern Newton Dale Spring Needle Eye Beck Killing Nab Scar Path (um) CS Und W E Track Beulah Wood Waterfall Yaul Sike Waterpale Slack Drain Hut Slack Path CS Path Newton Dale Track Newton Dale Pifelhead Wood Pifelhead End Path (um) S Yaul Sike Hole Lockton High Moor Yewtree Scar Hut Slack CS Path (um) Saltergate Bridge ED & Bdy Saltergate Moor Wardle Rigg Ward CS Havern Beck Talbot Wood Track Havern Hudson's Cross Beck Newtondale Forest Drive Waterfalls Saltergate Kidstyle Waterpale Slack Farm Pickering Moor Pickering Moor Cropton Forest Cropton Forest FF Levisham Moor Saltergate Huggitt's Scar Pile of Stones Path (um) Path (um) Double Dike West Side Brow Saltergate Brow SS Scarfhill Beck Long Gill Path (um) Path Path (um) Hole of Horcum Horcum Wood Raindale Head Path (um) Waterhill Slack CS Path (um) Path (um) Long Gill Path (um) Raper's Moors Railway Sole Farm Post ED & Ward Bdy Track Track Earthwork Beck Path (um) Path Track Cargate Nab Slack Scarfhill Hole of Horcum Track Rigg Path (um) Post Waterpale Slack Track North Yorkshire Horcum Dike Tumuli Horcum Wood Path (um) Crompton Forest Post Pickering Moor Scarfhill Beck Hole of Horcum Scargill Levisham Beck Gate Tk S Path (um) Track Stone Beck Oak Tree Cottage Path (um) Lockton Low Moor Gallock CS Path (um) Hill Pickering Post Track Track Path (um) Path (um) Broadhead -

APPLICATION for IDA DESIGNATION North York Moors National Park International Dark Sky Reserve

North York Moors National Park Authority 1 APPLICATION FOR IDA DESIGNATION North York Moors National Park International Dark Sky Reserve 25 September 2020 Cover image: Polly A Baldwin North York Moors National Park International Dark Sky Reserve 25 September 2020 Contents 3 Foreword by the Chairs of the North 4 Lighting 6.2 Rawcliffe House Farm 63 York Moors and the Yorkshire Dales Management Plan 44 6.4 Sutton Bank National Parks 5 4.1 Lighting Audit 45 National Park Centre 67 4.2 Lighting Management Plan 45 6.5 The Fox and Hounds Inn, 1 Executive Summary 6 Ainthorpe, Whitby 68 4.3 Street Lighting 46 1.1 Letter from North York Moors National Park Authority 4.4 Planning Statements 7 Consultation 70 Interim CEO, Chris France 9 in the LMP 47 4.5 Dark Sky Lighting Scheme 48 1.2 Nomination 10 8 Summary: Threats 1.3 Meeting Eligibility and 4.6 Visitor Lighting 49 and Mitigations 74 Minimum Requirements 12 8.1 Non-residential Properties 75 5 Outreach 50 1.4 North York Moors National Park 8.2 Residential Properties 75 International Dark Sky Reserve 14 5.1 Dark Skies Festival 51 8.3 RAF Fylingdales and 5.2 Dark Sky Campaigns 53 Woodsmith Mine 75 2 North York Moors 5.3 Starmakers 56 National Park 20 8.4 New Developments 76 5.4 Star Tips for Profit and 8.5 Threats from Beyond the 2.1 Factfile 22 Dark Sky Friendly Marque 56 Reserve and Nearby Settlements 76 2.2 Governance 22 5.5 Dark Sky Grants 58 8.6 Satellite Constellations 77 2.3 Light Pollution: 5.6 Sutton Bank National Park Current Situation 24 Centre Stargazing Pavilion 58 9 The future 78 5.7