Who Was Wilmot? – an Inquiry Mark Mccarthy June 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Cant Be Coded Can Be Decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output What cant be coded can be decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/198/ Version: Public Version Citation: Evans, Oliver Rory Thomas (2016) What cant be coded can be decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake. PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of London. c 2016 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email “What can’t be coded can be decorded” Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake Oliver Rory Thomas Evans Phd Thesis School of Arts, Birkbeck College, University of London (2016) 2 3 This thesis examines the ways in which performances of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1939) navigate the boundary between reading and writing. I consider the extent to which performances enact alternative readings of Finnegans Wake, challenging notions of competence and understanding; and by viewing performance as a form of writing I ask whether Joyce’s composition process can be remembered by its recomposition into new performances. These perspectives raise questions about authority and archivisation, and I argue that performances of Finnegans Wake challenge hierarchical and institutional forms of interpretation. By appropriating Joyce’s text through different methodologies of reading and writing I argue that these performances come into contact with a community of ghosts and traces which haunt its composition. In chapter one I argue that performance played an important role in the composition and early critical reception of Finnegans Wake and conduct an overview of various performances which challenge the notion of a ‘Joycean competence’ or encounter the text through radical recompositions of its material. -

London Gazette

. 1S828. [ 1501 ] London Gazette. TUESDAY, JULY 26, 1831. By the KING. Vaux, our Chancellor of Great Britain; the Most Reverend Father in God Our right trusty and right A PROCLAMATION, entirely-beloved Councillor Edward Archbishop of Dedaring His Majesty's Pleasure touching His Royal York, Primate of England and Metropolitan ; Our Coronation, and the Solemnity thereof. right trusty and entirely-beloved Cousin and Coun- cillor Henry Marquess of Lansdowne, President of WILLIAM, R, Our Council; Our right trusty and well-beloved 'HEREAS We have resblved, by the favour Councillor John George Lord Durham, Keeper of and blessing of Almighty God, to celebrate the Onr Privy Seal; Our right trusty and right entirely- solemnity of Our Royal Coronation, and of the Co- beloved Cousins and Councillors Bernard Edward ronation of Our dearly-beloved Consort the Queen, Duke of Norfolk, Hereditary Earl Marshal of upon Thursday the eighth day of September England ; William Spencer Duke of Devonshire, next, at Our Palace at Westminster; and forasmuch Lord Chamberlain of Our Household ; Charles Duke as by ancient customs and usages of this realm, as of Richmond, Our Postmaster-General; George also in regard of divers tenures of sundry manors, Duke of Gordon ; George William Frederick Duke lands, and otheV'aereditaiuents, many of Our loving of Leeds j John Duke of Bedford; James Duke subjects do claim, and are bound to do and perform of Montrose ; Alexander Duke of Hamilton ; Wil- divers services on the said day and at the time of the liam Henry Duke of Portland; -

Slater V. Baker and Stapleton (C.B. 1767): Unpublished Monographs by Robert D. Miller

SLATER V. BAKER AND STAPLETON (C.B. 1767): UNPUBLISHED MONOGRAPHS BY ROBERT D. MILLER ROBERT D. MILLER, J.D., M.S. HYG. HONORARY FELLOW MEDICAL HISTORY AND BIOETHICS DEPARTMENT SCHOOL OF MEDICINE AND PUBLIC HEALTH UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN - MADISON PRINTED BY AUTHOR MADISON, WISCONSIN 2019 © ROBERT DESLE MILLER 2019 BOUND BY GRIMM BOOK BINDERY, MONONA, WI AUTHOR’S INTRODUCTION These unpublished monographs are being deposited in several libraries. They have their roots in my experience as a law student. I have been interested in the case of Slater v. Baker and Stapleton since I first learned of it in law school. I was privileged to be a member of the Yale School Class of 1974. I took an elective course with Dr. Jay Katz on the protection of human subjects and then served as a research assistant to Dr. Katz in the summers of 1973 and 1974. Dr. Katz’s course used his new book EXPERIMENTATION WITH HUMAN BEINGS (New York: Russell Sage Foundation 1972). On pages 526-527, there are excerpts from Slater v. Baker. I sought out and read Slater v. Baker. It seemed that there must be an interesting backstory to the case, but it was not accessible at that time. I then practiced health law for nearly forty years, representing hospitals and doctors, and writing six editions of a textbook on hospital law. I applied my interest in experimentation with human beings by serving on various Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) during that period. IRBs are federally required committees that review and approve experiments with humans at hospitals, universities and other institutions. -

Statutes and Rules for the British Museum

(ft .-3, (*y Of A 8RI A- \ Natural History Museum Library STATUTES AND RULES BRITISH MUSEUM STATUTES AND RULES FOR THE BRITISH MUSEUM MADE BY THE TRUSTEES In Pursuance of the Act of Incorporation 26 George II., Cap. 22, § xv. r 10th Decembei , 1898. PRINTED BY ORDER OE THE TRUSTEES LONDON : MDCCCXCYIII. PRINTED BY WOODFALL AND KINDER, LONG ACRE LONDON TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. PAGE Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees . 7 CHAPTER II. The Director and Principal Librarian . .10 Duties as Secretary and Accountant . .12 The Director of the Natural History Departments . 14 CHAPTER III. Subordinate Officers : Keepers and Assistant Keepers 15 Superintendent of the Reading Room . .17 Assistants . 17 Chief Messengers . .18 Attendance of Officers at Meetings, etc. -19 CHAPTER IV. Admission to the British Museum : Reading Room 20 Use of the Collections 21 6 CHAPTER V, Security of the Museum : Precautions against Fire, etc. APPENDIX. Succession of Trustees and Officers . Succession of Officers in Departments 7 STATUTES AND RULES. CHAPTER I. Of the Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees. 1. General Meetings of the Trustees shall chap. r. be held four times in the year ; on the second Meetings. Saturday in May and December at the Museum (Bloomsbury) and on the fourth Saturday in February and July at the Museum (Natural History). 2. Special General Meetings shall be sum- moned by the Director and Principal Librarian (hereinafter called the Director), upon receiving notice in writing to that effect signed by two Trustees. 3. There shall be a Standing Committee, standing . • Committee. r 1 1 t-» • 1 t> 1 consisting 01 the three Principal 1 rustees, the Trustee appointed by the Crown, and sixteen other Trustees to be annually appointed at the General Meeting held on the second Saturday in May. -

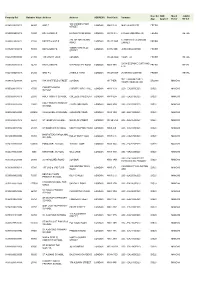

AMBER VALLEY VACANT INDUSTRIAL PREMISES SCHEDULE Address Town Specification Tenure Size, Sqft

AMBER VALLEY VACANT INDUSTRIAL PREMISES SCHEDULE Address Town Specification Tenure Size, sqft The Depot, Codnor Gate Ripley Good Leasehold 43,274 Industrial Estate Salcombe Road, Meadow Alfreton Moderate Freehold/Leasehold 37,364 Lane Industrial Estate, Alfreton Unit 1 Azalea Close, Clover Somercotes Good Leasehold 25,788 Nook Industrial Estate Unit A Azalea Close, Clover Somercotes Moderate Leasehold/Freehold 25,218 Nook Industrial Estate Block 19, Amber Business Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 25,200 Centre, Riddings Block 2 Unit 2, Amber Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 25,091 Business Centre, Riddings Unit 3 Wimsey Way, Alfreton Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 20,424 Trading Estate Block 24 Unit 3, Amber Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 18,734 Business Centre, Riddings Derby Road Marehay Moderate Freehold 17,500 Block 24 Unit 2, Amber Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 15,568 Business Centre, Riddings Unit 2A Wimsey Way, Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 15,543 Alfreton Trading Estate Block 20, Amber Business Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 14,833 Centre, Riddings Unit 2 Wimsey Way, Alfreton Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 14,543 Trading Estate Block 21, Amber Business Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 14,368 Centre, Riddings Three Industrial Units, Heage Ripley Good Leasehold 13,700 Road Industrial Estate Industrial premises with Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 13,110 offices, Nix’s Hill, Hockley Way Unit 2 Azalea Close, Clover Somercotes Good Leasehold 13,006 Nook Industrial Estate Derby Road Industrial Estate Heanor Moderate Leasehold 11,458 Block 23 Unit 2, Amber Alfreton Moderate -

No99 Jan 1987 Capital Gains-Our January Talk Advance Notice Beauty in History One Hundred Up

No99 of the CAMDEN HISTORY SOCIETY Jan 1987 Capital Gains-our January Beauty in History Thursday, Feb 5th, 8pm. Talk Burgh House, New End Square, NW3 Wednesday, January 21st, 7pm Holborn Central Library, Theobalds Rd WCl our talk in February has the unusual theme of beauty in history, more particularly the As members will be aware there has been a social and political implications of significant increase in archaeological personal appearance in western society from activity in London in the last decade. The 1500 to present day. This intriguing talk, Museum of London has recently mounted an to be given by Professor Arthur Marwick, exhibition to give perspective to the finds will be, of course, illustrated with and conclusions. We are therefore pleased slides. Professor Marwick is Head of the that Dr Hugh Chapman, of the Museum of Department of History at the Open London, has agreed to give us a talk on the_ University and is a frequent broadcaster. same theme, either to whet our appetites to He emphasises that his theme is to do with see the Exhibition or else to enlarge on physical beauty and not to do with fashion. what we have already seen. One Hundred Up Advance Notice Don't forget that the next Newsletter is Please put these dates in your new diaries: the one hundredth edition. We want to make it a larger edition that usual so if you Mar 25, 7.30pm. St Pancras Church House. have a short contribution do send it in to Jim Eliot on 'The City in Maps through the the editot, John Richardson, 32 Ellington ages' Street, N7 before February 15th. -

Chapter Eight: a Lost Way of Life – Farms in the Parish

Chapter Eight: A lost way of life – farms in the parish Like everywhere else in England, the farms in Edingale parish have consolidated, with few of the post-inclosure farms remaining now as unified businesses. Of the 13 farms listed here post-inclosure, only three now operate as full-time agricultural businesses based in the parish (ignoring the complication of Pessall Farm). While for more than 200 years, these farms were far and away the major employers in the parish, full-time non-family workers now account for fewer than ten people. Where this trend will finally end is hard to predict. Farms in Oakley As previously mentioned, the historic township of Oakley was split between the Catton and Elford estates. In 1939, a bible was presented to Mrs Anson, of Catton Hall, from the tenants and staff of the estate, which lists Mansditch, Raddle, Pessall Pitts, The Crosses, Donkhill Pits and Oakley House farms among others. So the Catton influence on Oakley extended well into the twentieth century. Oakley House, Oakley The Croxall registers record that the Haseldine family lived at Oakley, which we can presume to be Oakley House. The last entry for this family is 1620 and the registers then show two generations of the Dakin family living there: Thomas Dakin who died in 1657, followed by his son, Robert . Thomas was listed as being churchwarden of Croxall in 1626 and in 1633. Three generations of the Booth family then lived at Oakley House. John Booth, born in 1710, had seven children. His son George (1753-1836 ) married Catherine and they had thirteen children, including Charles (1788-1844) who married Anna Maria. -

Thomas Anson of Shugborough

Thomas Anson of Shugborough and The Greek Revival Andrew Baker October 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My interest in Thomas Anson began in 1982, when I found myself living in a cottage which had formerly been occupied by a seamstress on the Shugborough estate. In those days very little was known about him, just enough to suggest he was a person worth investigating, and little enough material available to give plenty of space for fantasy. In the early days, I was given a great deal of information about the background to 18th- century England by the late Michael Baigent, and encouragement by his friend and colleague Henry Lincoln (whose 1974 film for BBC’s “Chronicle” series, The Priest the Painter and the Devil introduced me to Shugborough) and the late Richard Leigh. I was grateful to Patrick, Earl of Lichfield, and Leonora, Countess of Lichfield, for their enthusiastic support. I presented my early researches at a “Holy Blood and Holy Grail” weekend at Shugborough. Patrick Lichfield’s step-grandmother, Margaret, Countess of Lichfield, provided comments on a particularly puzzling red-herring. Over the next twenty years the fantasies were deflated, but Thomas Anson remained an intriguing figure. I have Dr Kerry Bristol of Leeds University to thank for revealing that Thomas really was a kind of “eminence grise”, an influential figure behind the scenes of the 18th-century Greek Revival. Her 2006 conference at Shugborough was the turning point. The time was ripe for new discoveries. I wish to thank several researchers in different fields who provided important revelations along the way: Paul Smith, for the English translation from Chris Lovegrove, (former editor of the Journal of the Pendragon Society) of the first portion of Lady Anson’s letter referring to Honoré d’Urfé’s pastoral novel L’Astrée, written in French. -

CAMDEN STREET NAMES and Their Origins

CAMDEN STREET NAMES and their origins © David A. Hayes and Camden History Society, 2020 Introduction Listed alphabetically are In 1853, in London as a whole, there were o all present-day street names in, or partly 25 Albert Streets, 25 Victoria, 37 King, 27 Queen, within, the London Borough of Camden 22 Princes, 17 Duke, 34 York and 23 Gloucester (created in 1965); Streets; not to mention the countless similarly named Places, Roads, Squares, Terraces, Lanes, o abolished names of streets, terraces, Walks, Courts, Alleys, Mews, Yards, Rents, Rows, alleyways, courts, yards and mews, which Gardens and Buildings. have existed since c.1800 in the former boroughs of Hampstead, Holborn and St Encouraged by the General Post Office, a street Pancras (formed in 1900) or the civil renaming scheme was started in 1857 by the parishes they replaced; newly-formed Metropolitan Board of Works o some named footpaths. (MBW), and administered by its ‘Street Nomenclature Office’. The project was continued Under each heading, extant street names are after 1889 under its successor body, the London itemised first, in bold face. These are followed, in County Council (LCC), with a final spate of name normal type, by names superseded through changes in 1936-39. renaming, and those of wholly vanished streets. Key to symbols used: The naming of streets → renamed as …, with the new name ← renamed from …, with the old Early street names would be chosen by the name and year of renaming if known developer or builder, or the owner of the land. Since the mid-19th century, names have required Many roads were initially lined by individually local-authority approval, initially from parish named Terraces, Rows or Places, with houses Vestries, and then from the Metropolitan Board of numbered within them. -

Property Ref Rateable Value Address Address ADDRESS Post Code Surname App Applied Relief Rlf Cd

Disc Rel SBR Mand ·Addtnl Property Ref Rateable Value Address Address ADDRESS Post Code Surname App Applied Relief Rlf Cd 102 CAMDEN HIGH 00641010210011 64500 GND F LONDON NW1 0LU MUCHO MAS LTD FRESH STREET 00895006510018 18000 BST & GND FS 65 GRAYS INN ROAD LONDON WC1X 8TL FISHER LONDON LTD FRESH RETAIL 285-287 GRAYS INN C A MEDICAL (LONDON) 00895028530012 31500 BST PT & GND F LONDON WC1X 8QF FRESH ROAD LIMITED 12SBR3 GREVILLE 01182001230014 58000 BST & GND FS LONDON EC1N 8SB JERKKIES LIMITED FRESH STREET 01232019000006 21000 190 DRURY LANE LONDON WC2B 5QD V&ART UK FRESH RETAIL SARA BESPOKE CURTAINS 05006050910018 14250 BST & GND FS 509 FINCHLEY ROAD LONDON NW3 7BB FRESH RETAIL LTD 0122400021001A 24250 GND F L 2 NEALS YARD LONDON WC2H 9DP 26 GRAINS LIMITED FRESH RETAIL THE LONDON EARLY 0094100520000A 22000 54A WHITFIELD STREET LONDON W1T 4ER DR2000 MAND80 YEARS FOUNDATION CHRISTCHURCH 00000290107013 17500 CHRISTCHURCH HILL LONDON NW3 1JH LBC - EA200CE020 DIS20 MAND80 SCHOOL 00000290108016 22000 HOLY TRINITY SCHOOL COLLEGE CRESCENT LONDON NW3 5DN LBC - EA204CE020 DIS20 MAND80 HOLY TRINITY PRIMARY 00000290116008 20500 HARTLAND ROAD LONDON NW1 8DB LBC - EA205CE020 DIS20 MAND80 SCHOOL 00000290120003 203000 WILLIAM ELLIS SCHOOL HIGHGATE ROAD LONDON NW5 1QS LBC - EA315CE020 DIS20 MAND80 00000290123016 36250 ST JOSEPHS SCHOOL MACKLIN STREET LONDON WC2B 5NA LBC - EA215CE020 DIS20 MAND80 00000290137004 47250 ST DOMINICS SCHOOL SOUTHAMPTON ROAD LONDON NW5 4JS LBC - EA213CE020 DIS20 MAND80 HAMPSTEAD PAROCHIAL 00150099920008 34000 HOLLY BUSH VALE -

Penthouses Collection 8 Esther Anne Place

Penthouses Collection 8 Esther Anne Place ISLINGTON SQUARE 1 Contents 02 38 The Place to Live Historical The Place that Lives Ambassadors 04 40 The Pinnacle Premium of London Living Living 14 72 In and Around Material Palette Islington Square and Specifications 34 78 The Centre The Space to Live of Things The Space to Grow 36 104 Explore the Contact Whole of London 2 ISLINGTON SQUARE The Place to Live The Place that Lives Islington has a fascinating and diverse history. An exciting mix of independent businesses and boutiques, cultural venues and creative hubs makes it one of London’s most celebrated areas. In the heart of the community is Islington Square, a development that builds on the richness and variety of this neighbourhood. At the centre of the scheme is an Edwardian former Royal Mail sorting office, beautifully restored to its former grandeur and importance by CZWG Architects. Above grand new buildings, high arcades and a tree-lined boulevard, they have created fantastic apartments for living, arranged around calming internal landscaped courtyards. This vibrant addition to Islington includes a prestigious collection of shops, cafés and restaurants alongside warehouse-style apartments. There will be a luxury cinema, The Lounge by Odeon; a 40,000 square foot Third Space premier gym and a new landmark public art commission. It is a city within a city. At the heart of CZWG Architects’ stunning designs for Islington Square 2 THE SCHEME is the lovingly restored Edwardian former sorting office building. ISLINGTON SQUARE 3 The Pinnacle of London Living CZWG Architects are renowned for their outstanding schemes that astound and inspire. -

Hampstead and Highgate Past

No 111 of the CAMDEN HISTORY SOCIETY Jan 1989 Sounds from the Past Faking the Past Wed, 25th January, 6.30pm 20th February, 7.30pm Children's Library, St Marylebone Library, King of Bohemia, Hampstead High Street NW3 Marylebone Road, NWl. (nr Baker Street station). Entrance through main door of Philip Venning, the Director of the library. Society for the Preservation of Ancient One of the treasures of Britain, Buildings is our speaker on the 20th. He surprisingly unprivatised so far, is the will, of course, be telling us about the BBC Sound Archive. Regular radio listeners work of his Society, but he tells us that will be aware of its scope and grateful one of the concerns of his organisation is for it. We are joining with the St not just the preservation of old buildings Marylebone Society for this talk on the but the well-intentioned restoration or work and contents of this famous library, faking that goes on. to be given by Sally Hine, its archivist. STEPHEN WILSON BECOMES VICE-PRESIDENT Please note the earlier starting time! We are pleased to announce that one of our members, Stephen Wilson, has accepted our Poets on the Heath invitation to become a Vice-President of 16th March, 7.30pm the Society. Mr Wilson, who is now Rosslyn Hill Chapel, Rosslyn Hill, NW3. retired, was Keeper of the Public Records from October 1960, but prior to that he As mentioned in our previous Newsletter had spent much of his previous career in our talk in March is by Michael Foot MP, the Ministry of Transport and the Ministry on the theme of the poets associated with of Supply soon after the last War.