Sullivan, Scott, and Ivanhoe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Discourse in the Savoy Theatre's

SOCIAL DISCOURSE IN THE SAVOY THEATRE’S PRODUCTIONS OF THE NAUTCH GIRL (1891) AND UTOPIA LIMITED (1893): EXOTICISM AND VICTORIAN SELF-REFLECTION William L. Hicks, B.M. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2003 APPROVED: John Michael Cooper, Major Professor Margaret Notley, Committee Member Mark McKnight, Committee Member James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Hicks, William L, Social Discourse in the Savoy Theatre’s Productions of The Nautch Girl (1891) and Utopia Limited (1893): Exoticism and Victorian Self-Reflection. Master of Music (Musicology), August 2003, 107 pp., 4 illustrations, 12 musical examples, references, 91 titles. As a consequence to Gilbert and Sullivan’s famed Carpet Quarrel, two operettas with decidedly “exotic” themes, The Nautch Girl; or, The Rajah of Chutneypore, and Utopia Limited; or, The Flowers of Progress were presented to London audiences. Neither has been accepted as part of the larger Savoy canon. This thesis considers the conspicuous business atmosphere of their originally performed contexts to understand why this situation arose. Critical social theory makes it possible to read the two documents as overt reflections on British imperialism. Examined more closely, however, the operettas reveal a great deal more about the highly introverted nature of exotic representation and the ambiguous dialogue between race and class hierarchies in late nineteenth-century British society. Copyright, 2003 by William L. Hicks ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Because of the obscurity of The Nautch Girl and Utopia Limited, I am greatly indebted to the booksellers Christopher Browne and Wilfred M. -

THE MIKADO Gilbert & Sullivan

THE MIKADO Gilbert & Sullivan FESTIVAL THEATRE STATE OPERA SOUTH AUSTRALIA THE MIKADO A Comedic Opera in two acts Gilbert & Sullivan by Gilbert & Sullivan Orchestration by Eric Wetherell A Comedic Opera in two acts Orchestration by Eric Wetherell CREATIVES CAST Conductor - Simon Kenway Mikado - Pelham Andrews Director - Stuart Maunder Nanki Poo- Dominic J. Walsh Design - Simone Romaniuk Ko-Ko - Byron Coll Lighting Designer - Donn Byrnes Pooh-Bah - Andrew Collis Choreography - Siobhan Ginty Pish-Tush - Nicholas Cannon Associate Choreographer - Penny Martin Yum-Yum - Amelia Berry Repetiteur - Andrew George Pitti-Sing - Bethany Hill Peep-Bo - Charlotte Kelso Katisha - Elizabeth Campbell 9-23 NOVEMBER ADELAIDE FESTIVAL THEATRE STATE OPERA CHORUS The Mikado is an original ADELAIDE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA production by Opera Queensland. Director’s Note There is no theatrical phenomenon in the Antipodes The G&S operetta’s durability is extraordinary but with the staying power of Gilbert and Sullivan. not unexplainable. After all, Gilbert’s dramatic situations are still funny, and Sullivan’s music Our love affair with G&S (and let’s face it, how succeeds in providing a kind of romantic foil to many creators are instantly recognised by their Gilbert’s pervasive drollery and cynicism. This kind initials alone?) is almost as enduring as the works of friction was very much at the heart of Gilbert themselves. In the 1870s, when policing copyright and Sullivan’s creative relationship and the gentle was much trickier than it is now, two rival “pirate” satire alternating with genuine heartfelt emotion is productions of H.M.S. Pinafore were playing across a combination that never ages – indeed, perhaps it’s the street from one another in Melbourne. -

Sullivan-Journal

Sullivan-Journal Sullivan-Journal Nr. 4 (Dezember 2010) Die Wechselbeziehungen von Sullivans Werk und seiner Epoche sowie seine Leistungen und deren Würdigung sind in Deutschland bislang nur ansatzweise erforscht worden. Deshalb wer- fen wir in der neuen Ausgabe des Sullivan-Journals einen Blick auf den Beginn von Sullivans Laufbahn und deren Ausklang, indem wir uns mit seiner Freundschaft mit Charles Dickens und seinen Erfahrungen mit dem Musikfestival in Leeds befassen, insbesondere warum er dort die künstlerische Leitung abgeben musste. Zudem setzen wir uns aus unterschiedlichen Blickwin- keln mit Sullivans populärster Oper, The Mikado, auseinander: Wie sehen Japaner das Werk und steht dieses Stück noch in Einklang mit Sullivans Anforderungen an die Oper? Eine Übersicht über Sullivans Repertoire als Dirigent lenkt die Aufmerksamkeit auf Künstler und Werke, mit denen er sich intensiv auseinandergesetzt hat. Inhalt S. J. Adair Fitzgerald: Sullivans Freundschaft mit Dickens 2 Musical World (1886): Eine japanische Sicht auf The Mikado 4 Meinhard Saremba: Warum vertonte Sullivan The Mikado und The Rose of Persia? 7 Anne Stanyon: Das große Leeds-Komplott 27 Anhang Sullivans Repertoire als Dirigent 43 Sullivans London 48 Standorte der wichtigsten Manuskripte 49 1 S. J. Adair Fitzgerald Sullivans Freundschaft mit Dickens [Erstveröffentlichung in The Gilbert and Sullivan Journal Nr. 2, Juli 1925. Von S. J. Adair Fitzgerald erschien 1924 das Buch The Story of the Savoy Opera.] Charles Dickens hatte stets eine mehr oder weniger starke Neigung zur Musik. Es gibt Hinwei- se von seiner Schwester Fanny, die mit ihm die Lieder einstudierte, die er Bartley, dem Büh- nenmanager am Covent Garden Theatre, vorsingen sollte, als er versuchte, auch selbst auf der Bühne aufzutreten und gegebenfalls Unterhaltungsabende zu bieten wie Charles Mathews seni- or. -

Recitative in the Savoy Operas

Recitative in the Savoy Operas James Brooks Kuykendall In the early 1870s, London music publisher Boosey & Co. launched a new venture to widen its potential market. Boosey’s repertoire had been domestic music for amateur vocalists and pianists: drawing-room ballads and both piano/vocal and solo piano scores across the range of standard Downloaded from operatic repertory of the day, published always with a singing translation in English and often substituting Italian texts for works originally in French or German. Rossini, Donizetti, Bellini, and Verdi, Auber, Meyerbeer, Gounod, and Lecocq, Mozart, Beethoven, Weber, and Wagner all appeared in Boosey’s Royal Edition of Operas series, together http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ with a handful of “English” operas by Michael William Balfe and Julius Benedict. The new effort supplemented this domestic repertory with one aimed at amateur theatricals: “Boosey & Co.’s Comic Operas and Musical Farces.” The cartouche for this series is reproduced in figure 1, shown here on the title page of Arthur Sullivan’s 1867 collaboration with Francis C. Burnand, The Contrabandista. Seven works are listed as part of the new imprint, although three by guest on May 11, 2013 of these (Gounod, Lecocq, and Offenbach’s Grand Duchess) had been issued as part of the Royal Edition. Albert Lortzing’s 1837 Zar und Zimmermann masquerades as Peter the Shipwright, and it appeared with an English text only. The new series may well have been the idea of Sullivan himself. He had been retained by Boosey since the late 1860s as one of the general editors for the Royal Edition. -

Download Booklet

HarmoniousThe EchoSONGS BY SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN MARY BEVAN • KITTY WHATELY soprano mezzo-soprano BEN JOHNSON • ASHLEY RICHES tenor bass-baritone DAVID OWEN NORRIS piano Sir Arthur Sullivan, Ottawa, 1880 Ottawa, Sullivan, Arthur Sir Photograph by Topley, Ottawa, Canada /Courtesy of David B. Lovell Collection Sir Arthur Sullivan (1842 – 1900) Songs COMPACT DISC ONE 1 King Henry’s Song (1877)* 2:23 (‘Youth will needs have dalliance’) with Chorus ad libitum from incidental music to Henry VIII (1613) by William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616) and John Fletcher (1579 – 1625) Andante moderato Recording sponsored by Martin Yates 3 2 The Lady of the Lake (1864)† 3:25 from Kenilworth, ‘A Masque of the Days of Queen Elizabeth’, Op. 4 (or The Masque at Kenilworth) (1864) Libretto by Henry Fothergill Chorley (1808 – 1872) Allegro grazioso 3 I heard the nightingale (1863)‡ 2:59 Dedicated to his Friend Captain C.J. Ottley Allegretto moderato 4 Over the roof (1864)† 3:04 from the opera The Sapphire Necklace, or the False Heiress Libretto by Henry Fothergill Chorley Allegretto moderato Recording sponsored by Michael Symes 4 5 Will He Come? (1865)§ 4:05 Dedicated to The Lady Katherine Coke Composed expressly for Madame Sainton Dolby Moderato e tranquillo – Quasi Recitativo – Tranquillo un poco più lento Recording sponsored by Michael Tomlinson 6 Give (1867)† 4:56 Composed and affectionately dedicated to Mrs Helmore Allegretto – Un poco più lento – Lento Recording sponsored by John Thrower in memory of Simon and Brenda Walton 7 Thou art weary (1874)§ 5:00 Allegro vivace e agitato – Più lento – Allegro. Tempo I – Più lento – Allegro. -

GILBERT and SULLIVAN: Part 1

GILBERT AND SULLIVAN: Part 1 GILBERT AND SULLIVAN Part 1: The Correspondence, Diaries, Literary Manuscripts and Prompt Copies of W. S. Gilbert (1836-1911) from the British Library, London Contents listing PUBLISHER'S NOTE CONTENTS OF REELS CHRONOLOGY 1836-1911 DETAILED LISTING GILBERT AND SULLIVAN: Part 1 Publisher's Note "The world will be a long while forgetting Gilbert and Sullivan. Every Spring their great works will be revived. … They made enormous contributions to the pleasure of the race. They left the world merrier than they found it. They were men whose lives were rich with honest striving and high achievement and useful service." H L Mencken Baltimore Evening Sun, 30 May 1911 If you want to understand Victorian culture and society, then the Gilbert and Sullivan operas are an obvious starting point. They simultaneously epitomised and lampooned the spirit of the age. Their productions were massively successful in their own day, filling theatres all over Britain. They were also a major Victorian cultural export. A new show in New York raised a frenzy at the box office and Harper's New Monthly Magazine (Feb 1886) stated that the "two men have the power of attracting thousands and thousands of people daily for months to be entertained”. H L Mencken's comments of 1911 have proved true. Gilbert & Sullivan societies thrive all over the world and new productions continue to spring up in the West End and on Broadway, in Buxton and Harrogate, in Cape Town and Sydney, in Tokyo and Hong Kong, in Ottawa and Philadelphia. Some of the topical references may now be lost, but the basis of the stories in universal myths and the attack of broad targets such as class, bureaucracy, the legal system, horror and the abuse of power are as relevant today as they ever were. -

Style in the Music of Arthur Sullivan: an Investigation

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Style in the Music of Arthur Sullivan: An Investigation Thesis How to cite: Strachan, Martyn Paul Lambert (2018). Style in the Music of Arthur Sullivan: An Investigation. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2017 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000e13e Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk STYLE IN THE MUSIC OF ARTHUR SULLIVAN: AN INVESTIGATION BY Martyn Paul Lambert Strachan MA (Music, St Andrews University, 1983) ALCM (Piano, 1979) Submitted 30th September 2017 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Open University 1 Abstract ABSTRACT Style in the Music of Arthur Sullivan: An Investigation Martyn Strachan This thesis examines Sullivan’s output of music in all genres and assesses the place of musical style within them. Of interest is the case of the comic operas where the composer uses parody and allusion to create a persuasive counterpart to the libretto. The thesis attempts to place Sullivan in the context of his time, the conditions under which he worked and to give due weight to the fact that economic necessity often required him to meet the demands of the market. -

Midwestern Gilbert and Sullivan Society

NEWSLETTER OF THE MIDWESTERN GILBERT AND SULLIVAN SOCIETY September 1990 -- Issue 27 But the night has been long, Ditto, Ditto my song, And thank goodness they're both of 'em over! It isn't so much that the night was long, but that the Summer was (or wasn't, as the case may be). This was not one of S/A Cole's better seasons: in June, her family moved to Central Illinois; in July, the computer had a head crash that took until August to fix, and in that month, she was tired and sick from all the summer excitement. But, tush, I am puling. Now that Autumn is nearly here, things are getting back to normal (such as that is). Since there was no summer Nonsense, there is all kinds of stuff in this issue, including the answers to the Big Quiz, an extended "Where Can it Be?/The G&S Shopper", reports on the Sullivan Festival and MGS Annual Outing, and an analysis of Thomas Stone's The Savoyards' Patience. Let's see what's new. First of all, we owe the Savoy-Aires an apology. Oh, Members, How Say You, S/A Cole had sincerely believed that an issue of the What is it You've Done? Nonsense would be out in time to promote their summer production of Yeomen. As we know now, Member David Michaels appeared as the "First no Nonsense came out, and the May one didn't even Yeomen" in the Savoy-Aires' recent production of mention their address. Well, we're going to start to The Yeomen of the Guard. -

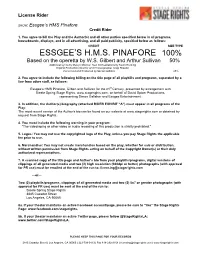

Essgee's H.M.S. Pinafore 100%

License Rider SHOW: Essgee’s HMS Pinafore Credit Rider 1. You agree to bill the Play and the Author(s) and all other parties specified below in all programs, houseboards, displays, and in all advertising, and all paid publicity, specified below as follows: CREDIT SIZE TYPE ESSGEE’S H.M.S. PINAFORE 100% Based on the operetta by W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan 50% Additional Lyrics by Melvyn Morrow New Orchestrations by Kevin Hocking Original Production Director and Choreographer Craig Shaefer Conceived and Produced by Simon Gallaher 25% 2. You agree to include the following billing on the title page of all playbills and programs, separated by a line from other staff, as follows: Essgee’s HMS Pinafore, Gilbert and Sullivan for the 21st Century, presented by arrangement with Steele Spring Stage Rights, www.stagerights.com, on behalf of David Spicer Productions, representing Simon Gallaher and Essgee Entertainment. 3. In addition, the Author(s) biography (attached RIDER EXHIBIT “A”) must appear in all programs of the Play: The most recent version of the Author’s bio can be found on our website at www.stagerights.com or obtained by request from Stage Rights. 4. You must include the following warning in your program: "The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited." 5. Logos: You may not use the copyrighted logo of the Play, unless you pay Stage Rights the applicable fee prior to use. 6. Merchandise: You may not create merchandise based on the play, whether for sale or distribution, without written permission from Stage Rights acting on behalf of the Copyright Owner(s) or their duly authorized representatives. -

Princess Ida

Princess Ida LET’S STUDY A PLAY TOGETHER Summer 2012 Princess Ida CONTENT PLANNED FOR TODAY’S CLASS: • William Schenk Gilbert • Arthur Sullivan • G&S Collaboration • D’Oyly Carte’s role • Savoy Theater • G&S – output 2 Princess Ida TODAY’S CLASS CONTENT (cont.) • Topsy Turvy trailer • Class discussion • Update on where our characters are now (Act II, start of Scene 4) • Read Act II, III to end 3 Princess Ida William Schwenk Gilbert (1836 -1911 ): • Gifted writer and librettist • Came from a nautical family • Educated as a lawyer, but unsuccessful in that field • Wrote satires, short stories, humorous poetry before meeting Sullivan • Wrote an earlier “Princess Ida” 4 Princess Ida • Gilbert (1879) 5 Princess Ida Sir W. Schwenk Gilbert 6 Princess Ida Arthur Sullivan (1842 -1900): • Gifted musician • Classically trained • Studied in Germany and Austria and held a Doctorate in Music • Was a well-regarded conductor • Wrote oratorios, operas, ballads, hymns, ballets, songs • Wrote the music for “Onward, Christian Soldiers” and “The Lost Chord” • A well-known Sullivan grand opera is “Ivanhoe” • Considered possibly “the best English composer of the 19th century” 7 Princess Ida • Sullivan (1870) 8 Princess Ida Sir Arthur Sullivan 9 Princess Ida Richard D’Oyle Carte (1844 – 1901): • Musician, ran a theatrical management company • Desired to start a light opera company in London • Had produced Sullivan’s “Cox and Box” • Introduced Gilbert to Sullivan – result “Trial by Jury” and twelve more 10 Princess Ida Richard D’Oyly Carte (Cont.) • Opened the -

A Walking Tour of Sir Arthur Sullivan's London

A Walking Tour of Sir Arthur Sullivan’s London AUTHORS: Theodore C. Armstrong 2015 Connor M. Haley 2015 Nicolás R. Hewgley 2015 Gregory G. Karp-Neufeld 2014 James L. Megin III 2015 Evan J. Richard 2015 Jason V. Rosenman 2014 ADVISOR: Professor John Delorey, WPI SPONSORS: Sir Arthur Sullivan Society Robin Gordon-Powell, Liaison DATE SUBMITTED: 20 June 2013 A Walking Tour of Sir Arthur Sullivan’s London INTERACTIVE QUALIFYING PROJECT WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE AUTHORS: Theodore C. Armstrong (CS) 2015 Connor M. Haley (BME) 2015 Nicolás R. Hewgley (BBT/TH) 2015 Gregory G. Karp-Neufeld (MIS) 2014 James L. Megin III (CS) 2015 Evan J. Richard (RBE/ME) 2015 Jason V. Rosenman (ECE) 2014 ADVISOR: Professor John Delorey, WPI SPONSORS: Sir Arthur Sullivan Society Robin Gordon-Powell, Liaison DATE SUBMITTED: 20 June 2013 Abstract The Sir Arthur Sullivan Society seeks to educate the public on the life and works of Sir Arthur Sullivan, a 19th-century composer. This project researched the ideal components of, and implemented, a brochure based walking tour of Sir Arthur Sullivan’s London. Additional research into other walking tour formats was conducted. Additionally cultural research of London was also conducted. i Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ..................................................................................................................................... 3 The Sir Arthur Sullivan -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Style in the Music of Arthur Sullivan: An Investigation Thesis How to cite: Strachan, Martyn Paul Lambert (2018). Style in the Music of Arthur Sullivan: An Investigation. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2017 The Author Version: Version of Record Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk STYLE IN THE MUSIC OF ARTHUR SULLIVAN: AN INVESTIGATION BY Martyn Paul Lambert Strachan MA (Music, St Andrews University, 1983) ALCM (Piano, 1979) Submitted 30th September 2017 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Open University 1 Abstract ABSTRACT Style in the Music of Arthur Sullivan: An Investigation Martyn Strachan This thesis examines Sullivan’s output of music in all genres and assesses the place of musical style within them. Of interest is the case of the comic operas where the composer uses parody and allusion to create a persuasive counterpart to the libretto. The thesis attempts to place Sullivan in the context of his time, the conditions under which he worked and to give due weight to the fact that economic necessity often required him to meet the demands of the market. The influence of his early training is examined as well as the impact of the early Romantic German school of composers such as Mendelssohn, Schubert and Schumann.