'She Had Always Been a Difficult Case …'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GP Text Paste Up.3

FACING ASIA A History of the Colombo Plan FACING ASIA A History of the Colombo Plan Daniel Oakman Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/facing_asia _citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry Author: Oakman, Daniel. Title: Facing Asia : a history of the Colombo Plan / Daniel Oakman. ISBN: 9781921666926 (pbk.) 9781921666933 (eBook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Economic assistance--Southeast Asia--History. Economic assistance--Political aspects--Southeast Asia. Economic assistance--Social aspects--Southeast Asia. Dewey Number: 338.910959 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Emily Brissenden Cover: Lionel Lindsay (1874–1961) was commissioned to produce this bookplate for pasting in the front of books donated under the Colombo Plan. Sir Lionel Lindsay, Bookplate from the Australian people under the Colombo Plan, nla.pic-an11035313, National Library of Australia Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press First edition © 2004 Pandanus Books For Robyn and Colin Acknowledgements Thank you: family, friends and colleagues. I undertook much of the work towards this book as a Visiting Fellow with the Division of Pacific and Asian History in the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University. There I benefited from the support of the Division and, in particular, Hank Nelson and Donald Denoon. -

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 41 February 2007 Compiled for the ANHG by Rod Kirkpatrick, 13 Sumac Street, Middle Park, Qld, 4074. Ph. 07-3279 2279. Email: [email protected] The publication is independent. 41.1 COPY DEADLINE AND WEBSITE ADDRESS Deadline for next Newsletter: 30 April 2007. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] The Newsletter is online through the “Publications” link of the University of Queensland’s School of Journalism & Communication Website at www.uq.edu.au/sjc/ and through the ePrint Archives at the University of Queensland at http://espace.uq.edu.au/) 41.2 EDITOR’S NOTE Please note my new email address: [email protected] I am on long service leave until early July. New subscriptions rates now apply for ten hard-copy issues of the Newsletter: $40 for individuals; and $50 for institutions. CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS: METROPOLITAN 41.3 COONAN MEDIA LAWS: WHEN WILL THEY TAKE EFFECT? The big question Australian media owners want answered as 2007 hits its straps is: when will the Coonan media laws take effect? Mark Day discusses many of the possible outcomes of an early or late introduction of the laws in the Media section of the Australian, 1 February 2007, pp.15-16. 41.4 NEWS WINS APPROVAL FOR FPC, PART 2 News Limited is set to increase its stable of local publications after the competition regulator said it would not oppose its acquisition of the remainder of Sydney-based Federal Publishing Company. News is negotiating with publisher Michael Hannan to acquire FPC’s 18 community newspapers in Queensland and NSW. -

Water Politics in Victoria: the Impact of Legislative Design, Policy

Water Politics in Victoria The impact of legislative design, policy objectives and institutional constraints on rural water supply governance Benjamin David Rankin Thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Swinburne Institute for Social Research Faculty of Health, Arts and Design Swinburne University of Technology 2017 i Abstract This thesis explores rural water supply governance in Victoria from its beginnings in the efforts of legislators during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to shape social and economic outcomes by legislative design and maximise developmental objectives in accordance with social liberal perspectives on national development. The thesis is focused on examining the development of Victorian water governance through an institutional lens with an intention to explain how the origins of complex legislative and administrative structures later come to constrain the governance of a policy domain (water supply). Centrally, the argument is concentrated on how the institutional structure comprising rural water supply governance encouraged future water supply endeavours that reinforced the primary objective of irrigated development at the expense of alternate policy trajectories. The foundations of Victoria’s water legislation were initially formulated during the mid-1880s and into the 1890s under the leadership of Alfred Deakin, and again through the efforts of George Swinburne in the decade following federation. Both regarded the introduction of water resources legislation as fundamentally important to ongoing national development, reflecting late nineteenth century colonial perspectives of state initiated assistance to produce social and economic outcomes. The objectives incorporated primarily within the Irrigation Act (1886) and later Water Acts later become integral features of water governance in Victoria, exerting considerable influence over water supply decision making. -

How Foreign Correspondents Risked Capture, Torture and Death to Cover World War II by Ray Moseley

2017-042 12 May 2017 Reporting War: How Foreign Correspondents Risked Capture, Torture and Death to Cover World War II by Ray Moseley. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2017. Pp. xiii, 421. ISBN 978–0–300–22466–5. Review by Donald Lateiner, Ohio Wesleyan University ([email protected]). As a child, Ray Moseley listened to reporters of World War II on the radio. He later came to know fourteen of them, but they never spoke of their experiences and he never asked (xi)—a missed oppor- tunity many of us have experienced with the diminishing older generation. 1 Moseley himself was a war and foreign correspondent for forty years from 1961, so he knows the territory from the inside out. He was posted to Moscow, Berlin, Belgrade, and Cairo, among many newspaper datelines. His book is an account and tribute to mostly British and American reporters who told “the greatest story of all time” (1, unintended blasphemy?). 2 He does not include World War II photographers as such, 3 but offers photos taken of many reporters. As usual, the European theater gets fuller attention than the Pacific (17 of the book’s 22 chapters). By design, breadth of coverage here trumps depth.4 Moseley prints excerpts from British, Australian, Canadian, Soviet, South African, Danish, Swedish, French, and Italian reporters. He excludes Japanese and German correspondents because “no independent reporting was possible in those countries” (x). This is a shame, since a constant thread in the reports is the relentless, severe censorship in occupied countries, invaded and invading Allied authorities, and the American and British Armed Forces them- selves. -

The Banning of E.A.H. Laurie at Melbourne Teachers' College, 1944

THE BANNING OF E.A.H. LAURIE AT MELBOURNE TEACHERS' COLLEGE, 1944. 05 Rochelle White DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES Fourth Year Honours Thesis Faculty of Arts, Victoria University. December, 1997 FTS THESIS 323.4430994 WHI 30001004875359 White, Rochelle The banning of E.A.H. Laurie at Melbourne Teachers' College, 1944 TABLE OF CONTENTS Synopsis i Disclaimer ii Acknowledgments iii Chapter 1: Introduction 1-3 Chapter 2: Background 4-14 Chapters: Events 15-23 Chapter 4: Was the ban warranted? 24-29 Chapters: Conclusion 30-31 Bibliography Appendix: Constitution Alteration (War Aims and Reconstruction ) Bill - 1942 SYNOPSIS This thesis examines the banning of a communist speaker. Lieutenant E.A.H. Laurie, at Melbourne Teachers' College in July, 1944 and argues that the decision to ban Laurie was unwarranted and politically motivated. The banning, which was enforced by the Minister for Public Instruction, Thomas Tuke Hollway, appears to have been based on Hollway's firm anti-communist views and political opportunism. A. J. Law, Principal of the Teachers' College, was also responsible for banning Laurie. However, Law's decision to ban Laurie was probably directed by Hollway and supported by J. Seitz, Director of Education. Students at the neighbouring Melbourne University protested to defend the rights of Teachers' College students for freedom of speech. The University Labor Club and even the University Conservative Club argued that Hollway should have allowed Laurie to debate the "Yes" case for the forthcoming 1944 Powers Referendum. The "Fourteen Powers Referendum" sought the transfer of certain powers from the States to the Commonwealth for a period of five years after the war, to aid post-war reconstruction. -

Earle Page and the Imagining of Australia

‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA ‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA STEPHEN WILKS Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, Or what’s a heaven for? Robert Browning, ‘Andrea del Sarto’ The man who makes no mistakes does not usually make anything. Edward John Phelps Earle Page as seen by L.F. Reynolds in Table Talk, 21 October 1926. Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463670 ISBN (online): 9781760463687 WorldCat (print): 1198529303 WorldCat (online): 1198529152 DOI: 10.22459/NPM.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This publication was awarded a College of Arts and Social Sciences PhD Publication Prize in 2018. The prize contributes to the cost of professional copyediting. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: Earle Page strikes a pose in early Canberra. Mildenhall Collection, NAA, A3560, 6053, undated. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS Illustrations . ix Acknowledgements . xi Abbreviations . xiii Prologue: ‘How Many Germans Did You Kill, Doc?’ . xv Introduction: ‘A Dreamer of Dreams’ . 1 1 . Family, Community and Methodism: The Forging of Page’s World View . .. 17 2 . ‘We Were Determined to Use Our Opportunities to the Full’: Page’s Rise to National Prominence . -

The Shelf Life of Zora Cross

THE SHELF LIFE OF ZORA CROSS Cathy Perkins A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Research in History University of Sydney 2016 Cathy Perkins, Zora Cross, MA thesis, 2016 I declare that the research presented here is my own original work and has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of a degree. Signed: Cathy Perkins Date: 14 July 2016 ii Cathy Perkins, Zora Cross, MA thesis, 2016 Abstract Zora Cross (1890–1964) is considered a minor literary figure, but 100 years ago she was one of Australia’s best-known authors. Her book of poetry Songs of Love and Life (1917) sold thousands of copies during the First World War and met with rapturous reviews. She was one of the few writers of her time to take on subjects like sex and childbirth, and is still recognised for her poem Elegy on an Australian Schoolboy (1921), written after her brother was killed in the war. Zora Cross wrote an early history of Australian literature in 1921 and profiled women authors for the Australian Woman’s Mirror in the late 1920s and early 1930s. She corresponded with prominent literary figures such as Ethel Turner, Mary Gilmore and Eleanor Dark and drew vitriol from Norman Lindsay. This thesis presents new ways of understanding Zora Cross beyond a purely literary assessment, and argues that she made a significant contribution to Australian juvenilia, publishing history, war history, and literary history. iii Cathy Perkins, Zora Cross, MA thesis, 2016 Acknowledgements A version of Chapter 3 of this thesis was published as ‘A Spoonful of Blood’ in Meanjin 73, no. -

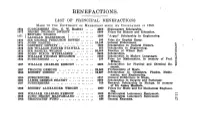

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE to the UNIVERSITY Oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION in 1853

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE TO THE UNIVERSITY oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION IN 1853. 1864 SUBSCRIBERS (Sec, G. W. Rusden) .. .. £866 Shakespeare Scholarship. 1871 HENRY TOLMAN DWIGHT 6000 Prizes for History and Education. 1871 j LA^HL^MACKmNON I 100° "ArSUS" S«h°lar8hiP ln Engineering. 1873 SIR GEORGE FERGUSON BOWEN 100 Prize for English Essay. 1873 JOHN HASTIE 19,140 General Endowment. 1873 GODFREY HOWITT 1000 Scholarships in Natural History. 1873 SIR WILLIAM FOSTER STAWELL 666 Scholarship in Engineering. 1876 SIR SAMUEL WILSON 30,000 Erection of Wilson Hall. 1883 JOHN DIXON WYSELASKIE 8400 Scholarships. 1884 WILLIAM THOMAS MOLLISON 6000 Scholarships in Modern Languages. 1884 SUBSCRIBERS 160 Prize for Mathematics, in memory of Prof. Wilson. 1887 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 2000 Scholarships for Physical and Chemical Re search. 1887 FRANCIS ORMOND 20,000 Professorship of Music. 1890 ROBERT DIXSON 10,887 Scholarships in Chemistry, Physics, Mathe matics, and Engineering. 1890 SUBSCRIBERS 6217 Ormond Exhibitions in Music. 1891 JAMES GEORGE BEANEY 8900 Scholarships in Surgery and Pathology. 1897 SUBSCRIBERS 760 Research Scholarship In Biology, in memory of Sir James MacBain. 1902 ROBERT ALEXANDER WRIGHT 1000 Prizes for Music and for Mechanical Engineer ing. 1902 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 1000 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 JOHN HENRY MACFARLAND 100 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 GRADUATES' FUND 466 General Expenses. BENEFACTIONS (Continued). 1908 TEACHING STAFF £1160 General Expenses. oo including Professor Sponcer £2riS Professor Gregory 100 Professor Masson 100 1908 SUBSCRIBERS 106 Prize in memory of Alexander Sutherland. 1908 GEORGE McARTHUR Library of 2600 Books. 1004 DAVID KAY 6764 Caroline Kay Scholarship!!. 1904-6 SUBSCRIBERS TO UNIVERSITY FUND . -

Provenance 2015

Provenance 2015 Issue 14, 2015 ISSN: 1832-2522 Index About Provenance 2 Editorial 4 Refereed articles 6 Patricia Grimshaw and Hannah Loney ‘Doing their bit helping make Australia free’: Mothers of Aboriginal diggers and the assertion of Indigenous rights 7 James Kirby Beyond failure and success: The soldier settlement on Ercildoune Road 18 Cassie May Lithium and lost souls: The role of Bundoora Homestead as a repatriation mental hospital 1920–1993 30 Dr Cate O’Neill ‘She had always been a difficult case …’ : Jill’s short, tragic life in Victoria’s institutions, 1952–1955 40 Amber Graciana Evangelista ‘… From squalor and vice to virtue and knowledge …’: The rise of Melbourne’s Ragged School system 56 Barbara Minchinton Reading the papers: The Victorian Lands Department’s influence on the occupation of the Otways under the nineteenth century land Acts 71 Peter Davies, Susan Lawrence and Jodi Turnbull Historical maps, geographic information systems (GIS) And complex mining landscapes on the Victorian goldfields 85 Forum articles 93 Dr David J Evans John Jones: A builder of early West Melbourne 94 Jennifer McNeice Military exemption courts in 1916: A public hearing of private lives 106 Dorothy Small An Innocent Pentonvillain: Thomas Drewery, chemist and exile 1821-1859 115 Janet Lynch The families of World War I veterans: Mental illness and Mont Park 123 Research journeys 130 Jacquie Browne Who says ‘you can’t change history’? 131 1 About Provenance The journal of Public Record Office Victoria Provenance is a free journal published online by Editorial Board Public Record Office Victoria. The journal features peer- reviewed articles, as well as other written contributions, The editorial board includes representatives of: that contain research drawing on records in the state • Public Record Office Victoria access services; archives holdings. -

Articles 'The Silence of the Sphinx': the Delay in Organising Media

‘FAILED’ STATES AND THE ENVIRONMENT Articles ‘The silence of the Sphinx’: The delay in organising media coverage of World War II ABSTRACT None of those New Zealand men who served as official war correspondents in World War II are alive today to tell their stories. It is left to the media historian to try and piece together their lives and actions, always regret- ting that research had not started sooner. Sadly there is more information available about World War I and the life and actions of Malcolm Ross, the country’s first official war correspondent, than there is about New Zea- land’s World War II correspondents. Nevertheless, remembering the work of these journalists is important, so this is a first attempt at chronicling the circumstances surrounding the appointment of the first of the official correspondents, John Herbert Hall and Robin Templeton Miller, for the 1939-45 conflict. The story of the appointment of men to cover the war, whether as press correspondents, photographers, artists or broadcasters, is one of ‘absurd delays’ which were not resolved until nearly two years of the war had passed. Keywords: journalism history, New Zealand, newspapers, public relations, war correspondence ALLISON OOSTERMAN Auckland University of Technology HIS preliminary research focuses solely on the appointment of those official New Zealand correspondents sent expressly to cover the actions Tof the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) troops and covers up until the establishment of the Public Relations Office in May 1941. Many reporters PACIFIC JOURNALISM REVIEW 20 (2) 2014 187 pjr_20_2_October_2014 final.indd 187 31/10/2014 6:32:59 p.m. -

A Watergate Lawyer-Hero's World War II Nazi Camps-Response

A WATERGATE LAWYER-HERO’S WORLD WAR II NAZI CAMPS-RESPONSE: A CHESTERFIELD H. SMITH- CENTENARY REAPPRECIATION GEORGE S. SWAN I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 139 A. Chesterfield Harvey Smith, Senior: Watergate Lawyer- Hero ..................................................................................... 139 B. Chesterfield Harvey Smith, Senior: Second World War Hero ..................................................................................... 141 II. THE SATURDAY NIGHT MASSACRE, AND ITS AFTERMATH .............. 143 A. The Fever in America: October 1973 ................................. 143 B. The Climate in America: 1995-2003 .................................. 146 III. FIVE LIBERATED NAZI CAMP WARSTORIES .................................... 148 A. The Smith Papers Version: 2009 ......................................... 148 B. The Florida Bar Version: 2003, Regarding 1995 ............... 148 i. 1995 ............................................................................... 148 ii. 1993–1995 ..................................................................... 149 C. The Museum of Florida History Version: 1997 .................. 151 D. The Oral History Version: 2000 .......................................... 152 E. The Dr. Jim Wendell Version: 1999 .................................... 152 i. Dr. Wendell as Reliable ReporTer .................................. 153 ii. Wendell-SmiTh as Suspect Source ................................. 155 a. The Wendell-Smith -

Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels”: Looking Beyond the Myth Emma Rogerson

The “Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels”: looking beyond the myth Emma Rogerson Abstract The popular myth of the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels has throughout the generations asserted the belief that Papuan carriers, during the 1942 battle for Kokoda, willingly provided assistance to the Australian war effort as volunteers. However, contradictions surround the history of the Papuan carriers concerning their recruitment, treatment, and working conditions. The contrasting stories of Papuan experiences as carriers have been left out of Australian memory for a number of reasons. This exclusion has in turn affected the way Papuans see their role as carriers in post-war history, and also raises issues of recognition, compensation and remembrance. William Dargie, Stretcher bearers in the Owen Stanleys, 1943, oil on canvas, 143.2 x 234.4 cm. AWM ART26653 2 Australian War Memorial, SVSS paper, 2012 Emma Rogerson, The “Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels”:looking beyond the myth ©Australian War Memorial Introduction The romanticised myth of the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels has lingered in Australian public memory since 1942, when Sapper Bert Beros of the 7th Division, Royal Australian Engineers, wrote the poem entitled “The Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels”. Expressing fondness towards the “black angels” who were assisting the Australians in the war against Japan, the poem found instant fame in Australian papers. Two months later George Silk, a photographer for the Australian Department of Information, captured what would become the iconic image of the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angel, a black-and-white photograph depicting blinded Australian Private George Whittington being led to a field hospital near Buna by carrier Raphael Oimbari. These two impressions of the Papuan carriers were strengthened by the attitudes and views of some Australian soldiers in war diaries, letters home and press reports, which led to the creation of the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angel myth.