Principals' Roles in Supporting and Evaluating Teacher Use Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio Essentials 2012

Artist Song Series Issue Track 44 When Your Heart Stops BeatingHitz Radio Issue 81 14 112 Dance With Me Hitz Radio Issue 19 12 112 Peaches & Cream Hitz Radio Issue 13 11 311 Don't Tread On Me Hitz Radio Issue 64 8 311 Love Song Hitz Radio Issue 48 5 - Happy Birthday To You Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 21 - Wedding Processional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 22 - Wedding Recessional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 23 10 Years Beautiful Hitz Radio Issue 99 6 10 Years Burnout Modern Rock RadioJul-18 10 10 Years Wasteland Hitz Radio Issue 68 4 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Radio Essential IssueSeries 44 Disc 44 4 1975, The Chocolate Modern Rock RadioDec-13 12 1975, The Girls Mainstream RadioNov-14 8 1975, The Give Yourself A Try Modern Rock RadioSep-18 20 1975, The Love It If We Made It Modern Rock RadioJan-19 16 1975, The Love Me Modern Rock RadioJan-16 10 1975, The Sex Modern Rock RadioMar-14 18 1975, The Somebody Else Modern Rock RadioOct-16 21 1975, The The City Modern Rock RadioFeb-14 12 1975, The The Sound Modern Rock RadioJun-16 10 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 4 2 Pistols She Got It Hitz Radio Issue 96 16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Radio Essential IssueSeries 23 Disc 23 3 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 16 21 Savage Feat. J. Cole a lot Mainstream RadioMay-19 11 3 Deep Can't Get Over You Hitz Radio Issue 16 6 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Hitz Radio Issue 46 6 3 Doors Down Be Like That Hitz Radio Issue 16 2 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Hitz Radio Issue 62 16 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Hitz Radio Issue 12 15 3 Doors Down Here Without You Hitz Radio Issue 41 14 3 Doors Down In The Dark Modern Rock RadioMar-16 10 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time Hitz Radio Issue 95 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Hitz Radio Issue 3 9 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Hitz Radio Issue 57 15 3 Doors Down One Light Modern Rock RadioJan-13 6 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Hitz Radio Issue 31 2 3 Doors Down Feat. -

Redox DAS Artist List for Period

Page: Redox D.A.S. Artist List for01.10.2020 period: - 31.10.2020 Date time: Title: Artist: min:sec 01.10.2020 00:01:07 A WALK IN THE PARK NICK STRAKER BAND 00:03:44 01.10.2020 00:04:58 GEORGY GIRL BOBBY VINTON 00:02:13 01.10.2020 00:07:11 BOOGIE WOOGIE DANCIN SHOES CLAUDIAMAXI BARRY 00:04:52 01.10.2020 00:12:03 GLEJ LJUBEZEN KINGSTON 00:03:45 01.10.2020 00:15:46 CUBA GIBSON BROTHERS 00:07:15 01.10.2020 00:22:59 BAD GIRLS RADIORAMA 00:04:18 01.10.2020 00:27:17 ČE NE BOŠ PROBU NIPKE 00:02:56 01.10.2020 00:30:14 TO LETO BO MOJE MAX FEAT JAN PLESTENJAK IN EVA BOTO00:03:56 01.10.2020 00:34:08 I WILL FOLLOW YOU BOYS NEXT DOOR 00:04:34 01.10.2020 00:38:37 FEELS CALVIN HARRIS FEAT PHARRELL WILLIAMS00:03:40 AND KATY PERRY AND BIG 01.10.2020 00:42:18 TATTOO BIG FOOT MAMA 00:05:21 01.10.2020 00:47:39 WHEN SANDRO SMILES JANETTE CRISCUOLI 00:03:16 01.10.2020 00:50:56 LITER CVIČKA MIRAN RUDAN 00:03:03 01.10.2020 00:54:00 CARELESS WHISPER WHAM FEAT GEORGE MICHAEL 00:04:53 01.10.2020 00:58:49 WATERMELON SUGAR HARRY STYLES 00:02:52 01.10.2020 01:01:41 ŠE IMAM TE RAD NUDE 00:03:56 01.10.2020 03:21:24 NO ORDINARY WORLD JOE COCKER 00:03:44 01.10.2020 03:25:07 VARAJ ME VARAJ SANJA GROHAR 00:02:44 01.10.2020 03:27:51 I LOVE YOU YOU LOVE ME ANTHONY QUINN 00:02:32 01.10.2020 03:30:22 KO LISTJE ODPADLO BO MIRAN RUDAN 00:03:02 01.10.2020 03:33:24 POROPOMPERO CRYSTAL GRASS 00:04:10 01.10.2020 03:37:31 MOJE ORGLICE JANKO ROPRET 00:03:22 01.10.2020 03:41:01 WARRIOR RADIORAMA 00:04:15 01.10.2020 03:45:16 LUNA POWER DANCERS 00:03:36 01.10.2020 03:48:52 HANDS UP / -

Get a PDF Copy of Morgan's Voice

Morgan's Voice POEMS& STORIES Morgan Segal Copyright © 1997 by RobertSegal All rights reserved. Library of CongressCataloging-in-Publication Data Segal,Morgan Morgan's Voice Poems8c Stories ISBN 0-9662027-0-8 First Edition 1997 Designedby RileySmith Printed in the United Statesof America by PacificRim Printers/Mailers 11924 W. Washington Blvd. LosAngeles, CA 90066 Printed on acid-free, recycled paper. The gift of sharing so intimately in Morgan's life, through her prose and poetry, is one all will commit to their hearts. Here are remembrances, emotionally inspired, of personal journeys through a landscape of experience that has been both tranquil and turbulent. Her poems are "pearls dancing," shimmering like her own life in an all too brief sunlight; her stories portraits, at times fragile, at times triumphant in their will to witness lasting humaness. She is tmly a talent and a presence too soon lost. -James Ragan, Poet Director, Professional Writing Program University of Southern California Morgan possessed a rare and beautiful soul. Those wide brown eyes of hers shone forth with a child's curiosity and innocence. But her heart was the heart of woman who was haunted by unfathomable darkness. Morgan's words are infused with depth, wisdom, honesty, courage and insight. Her descriptions reveal the intense thirst she had for even the most mundane aspects of life -- a fingernail, the scale of a fish, a grandfather's breath, a strand of hair. The attention she pays to details can help us to return to our lives with a renewed revereance for all the subtle miracles that surround us each moment. -

Unfinished Book of Poetry 2020

The Unfinished Book of Poetry 2020 poetry from five Cork City secondary schools Published by Cork City Council Published in 2020 by Cork City Council, Cork City Libraries and Schools Project Supported by the Arts Office, Cork City Council in partnership with Ó Bhéal The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means, adapted, rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owners. Applications for permissions should be addressed to the publisher. All rights reserved. Text © 2020 for each author as indicated www.obheal.ie Cover image, design and editing by Paul Casey Printed in Cork by City Print The Unfinished Book of Poetry 2020 Contents Foreword by Liam Ronayne, City Librarian 1 Assisting Writers’ Biographies 2 Gaelcholáiste Choilm Introduction by Bernadette Nic an tSaoir 4 Aoife Ní Bhruadair 8 An Tigín Bán // Chug Chug Chug // Mo Chúinne // Scéal mo Bheatha // No Sound // My Santa Claus // Birds of Glanworth // Grian agus Gealach // Proper New Yorkers // Sugar Butter Flour // Me and my Balloon // Haikú Art Óg Ó Gráda 16 Doire Fhíonáin Ciara Ní Aodha 17 Fadó // I am Invisible // My Species // The Girl on the Rocks // Dhá Haikú // Mise agus an Stáitse // Me and my Open Window // The Wisdom a Bird Possesses Cillian Ó Cathasaigh 23 Ceol Na nÉan // Licence to Kill // A Lost Hope // Haikú // Deireadh an Chogaidh // First Day at School David Ó Meachair -

Redox DAS Artist List for Period: 01.11.2020

Page: Redox D.A.S. Artist List for01.11.2020 period: - 30.11.2020 Date time: Title: Artist: min:sec 01.11.2020 00:02:37 TO NISI TI CHATEAU 00:04:00 01.11.2020 00:06:39 TANJA CHATEAU 00:04:14 01.11.2020 00:10:53 MIDDLE OF THE NIGHT MONSTA X 00:02:42 01.11.2020 00:13:46 STAY MY BABY AMY DIAMOND 00:03:00 01.11.2020 00:16:45 MAMBO NIKKI VIANNA 00:02:51 01.11.2020 00:19:37 SEI UN MITO 883 00:05:02 01.11.2020 00:24:37 ZARADI UPANJA NEISHA 00:03:06 01.11.2020 00:27:43 MOONWALK RMX LAURA 00:03:54 01.11.2020 00:31:38 MRS ROBINSON LEON LOPEZ 00:03:42 01.11.2020 00:35:20 DYNAMITE TAIO CRUZ 00:03:19 01.11.2020 00:38:46 WAKING UP SLOW GABRIELLE APLIN 00:03:22 01.11.2020 00:42:09 MY ARMS KEEP MISSING RICK ASTLEY 00:03:07 01.11.2020 00:45:13 SUMMER NIGHTS SURANNE JONES AND JONATHAN 00:03:33WILKES 01.11.2020 00:48:47 WITH EVERY BEAT OF MY HEART TAYLOR DAYNE 00:04:17 01.11.2020 00:53:03 QUE PIDES TO ALEX UBAGO 00:04:05 01.11.2020 00:57:07 IN THE NIGHT BILGERI 00:03:51 01.11.2020 01:01:01 MONEY S TOO TIGHT TO MENTIONVALENTINE BROTHERS 00:05:48 01.11.2020 01:06:49 GOOD BOYS (RMX) BLONDIE 00:03:38 01.11.2020 01:10:28 MISS SARAJEVO PASSENGERS 00:04:29 01.11.2020 01:15:05 NIHČE NI POPOLN GAME OVER 00:03:49 01.11.2020 01:18:55 ORPHANS COLDPLAY 00:03:16 01.11.2020 01:22:11 SATURDAY PARTY (STRUMP DUMPWALTER ) AND SIMON 00:04:16 01.11.2020 01:26:27 ONE OF US JUST FRIENDS 00:05:37 01.11.2020 01:32:03 EVERYWAY THAT I CAN SERTAB 00:02:34 01.11.2020 01:34:38 ZA ZMERAJ DAVID FEAT ANJA BAŠ 00:02:19 01.11.2020 01:36:58 WHAT S LOVE GOT TO DO WITH ITMARIA LUCIA 00:03:26 -

Partner Név Jellemző Művek 100 BANDS PUBLISHING LUCKY YOU /#/ RINGER /#/ SIT DOWN /#/ KILLSHOT /#/ GOOD GUY FEAT JESSIE REYEZ

Partner név Jellemző Művek 100 BANDS PUBLISHING LUCKY YOU /#/ RINGER /#/ SIT DOWN /#/ KILLSHOT /#/ GOOD GUY FEAT JESSIE REYEZ 13 MOONS MUSIC BLOW /#/ KEEP PLAYING /#/ KEEP ME UP ALL NIGHT /#/ TOGETHER WE RUN /#/ BIGROOM BLITZ (RADIO MIX) 14 PRODUCTIONS SARL TIC TIC TAC /#/ OU SONT LES REVES /#/ PLACE DES GRANDS HOMMES /#/ QUI A LE DROIT /#/ JE SERAI LA POUR LA SUITE 1794 MUSIC AMERICAN BOOK OF SECRETS CUES /#/ AMERICA S BOOK OF SECRETS CUES /#/ BMOC /#/ LIMO HIP HOP VER 4 /#/ JOURNEY THROUGH TIME 1819 BROADWAY MUSIC DAYDREAM /#/ STORY S OVER (THE) /#/ STORY S OVER /#/ DAYDREAM (DJ NEWIK & STARWHORES REMIX) /#/ VADONATÚJ ÉRZÉS 1916 PUBLISHING MIDDLE (THE) /#/ HATE ME /#/ RUIN MY LIFE /#/ SLOW DANCE /#/ IF IT AIN T LOVE 23DB MUSIC RAPTURE /#/ HONEST SLEEP /#/ PALM DREAMS /#/ FLOWERS AND YOU /#/ DNA 24 HOUR SERVICE STATION ON THE LOOKOUT 2L E-SCORE UBI CARITAS /#/ SERENITY /#/ SNOW IN NEW YORK, FOR PIANO /#/ HUDSON /#/ ROXBURY PARK, FOR PIANO 2WAYTRAFFIC UK RIGHTS LTD TODAY S NAME - MAI JÁTÉKOSOK /#/ TODAY S NAMES /#/ WHAT IS THE ORDER - SORREND 3 WEDDINGS MUSIC SOMETHING ABOUT DECEMBER /#/ MAKE ME BELIEVE AGAIN /#/ HERE S TO NEVER GROWING UP /#/ JET BLACK HEART (START AGAIN) /#/ LET ME GO 360 MUSIC PUBLISHING LTD ONLY ONE /#/ IF YOU KNEW /#/ DON T BELONG /#/ HUMANICA /#/ MINIMAL LIFE 386MUSIC DON T LET GO /#/ VIOLET ALONE 3BEAT MUSIC LIMITED QUESTIONS /#/ MAN BEHIND THE SUN /#/ CONNECTION /#/ WHO'S LOVING YOU (PART 1) /#/ LINK UP 4 REAL MUSIC ANGELS LANDING /#/ EUGINA 2000 50 CENT MUSIC BEST FRIEND /#/ HATE IT OR LOVE IT /#/ HUSTLER S AMBITION -

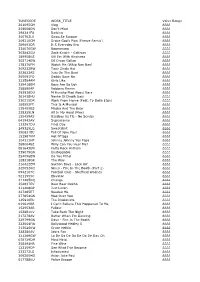

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When -

Merchants and Chamber Officials Express Guarded Optimism About

7= HOW TO OIF THE LEADER Just Fttl in the Form On Page 5 And Return It to Us! —Serving the Town Since 1890- UHWtM YEAR Thursday, December 3,1992 232-4407 FORTY CENTS ASSEMBLYMAN'S CONTINUED INTERCESSION SOUGHT State Historians Still Are Delaying Ttittle Parkway Bridge Replacement; Mayor Will Write Urging Action Councilman MacRitchie Suggests Moving Current Structure to Local Park; Union County Proposes New Bridge Over Creek Sear Springfield Avenue By ROBERT R. FASZCZEWSKI the historical officials had given it Mr. Brandt said permission also SiO Writumfir Tin Wttfild Indtr their imprimatur. would have to be granted from the Motorists who have been finding However, at Tuesday night 'sTown Westfield Veterinary Hospital and the other ways to get from the South to Council conference session Trans- Honeywell Corp., which have prop- the North Site of Westfield without portation, Parking and Traffic Safety erties adjacent to the creek for the using the Turtle Parkway Bridge for Committee Chairman Kenneth L. bridge project and a sidewalk it plans several years apparently will be MacRitchie reported the historians to install. waiting a while longer. still have held up the project. The council also gave tentative The bridge, which was built in Councilman MacRitchie, who said approval to resolutions approving Fire 1907, has remained closed to ve- the state should move the bridge to a Department and Public Works De- hicular traffic for some time because local park or some other site and partment salaries for 1993. it is in need of repair or replacement, replace it with a new one if it is such Town firefighters next year will according to state Department of a historically-significant structure, receive 5 per cent raises as part of the Transportation officials. -

AC/DC Nickelback Take That David Guetta David Bowie Max Raabe Unheilig Katherine Jenkins Olly Murs Sasha Anouar Brahem Inhalt

GRATIS | DEZEMBER 2014 / JANUAR 2015 Ausgabe 14 AC/DC NICKELBACK TAKE THAT DAVID GUETTA DAVID BOWIE MAX RAABE UNHEILIG KATHERINE JENKINS OLLY MURS SASHA ANOUAR BRAHEM INHALT INHALT EditiON – IMPRESSUM 03 HERBERT GRÖNEMEYER HERAUSGEBER 04 AC/DC AKTIV MUSIK MARKETING GMBH & CO. KG 05 NICKELBACK | TAKE THAT Steintorweg 8, 20099 Hamburg, UstID: DE 187995651 06 DAVID GUETTA | DAVID BOWIE PERSÖNLICH HAFTENDE GESELLSCHAFTERIN: 07 RAKEDE | RISE OF THE NORTHSTAR AKTIV MUSIK MARKETING 08 MAX RAABE | schillER VERWALTUNGS GMBH & CO. KG 09 FRANK SINATRA | COLDPLAY | SIDO Steintorweg 8, 20099 Hamburg 10 UNHEILIG | SISTER CRISTINA SITZ: Hamburg, HR B 100122 11 KATHERINE JENKINS | SHADY XV GESCHÄFTSFÜHRER Marcus-Johannes Heinz 12 THE VELVET UndErgrOUnd | FON: 040/468 99 28-0 Fax: 040/468 99 28-15 THE COMMON linnEts | SUPErtramP E-Mail: [email protected] 14 OLLY MURS | SASHA 15 THE NEW BASEMENT TAPES | MARY J. BLIGE | REDAKTIONS- UND ANZEIGENLEITUNG SOUNDGARDEN Daniel Ahrweiler (da) (verantwortlich für den Inhalt) 16 ANOUAR BRAHEM| IGGY AZALEA 17 THE HOBBIT | METALLICA | MITARBEITER DIESER AUSGABE DIE TribUTE VON PanEM Marcel Anders (ma), Helmut Blecher (hb), Dagmar 18 HELENE FISCHER | NinO DE ANGELO | HEinO Leischow (dl), Patrick Niemeier (nie), Steffen Rüth (sr), 19 NEUHEITEN Anja Wegner 23 PLATTENLADEN DES MONATS | PLATTENLÄDEN FOTOGRAFEN DIESER AUSGABE Bleibe auf dem Laufenden und bestelle unseren Newsletter auf Ellen von Unwerth (1 Herbert Grönemeyer, 6 David WWW.PLATTENLADENTIPPS.DE/NEWSLETTER Guetta), Ali Kepenek (3 Herbert Grönemeyer), James Minchin -

Creative Writing Anthology

Creative Writing Anthology Somerset County Teen Arts Festival 2016 Creative Writing Anthology The Somerset County Creative Writing Anthology is a component of the annual Somerset County Teen Arts Festival Program. Students’ creative writing is submitted to respected professional writers and/or Geraldine R. Dodge Poets who review the submissions and offer written critiques for each student. The professional writers engaged commend the students’ strong points and offer constructive suggestions for improving particular aspects of their work. At the festival, students attend feedback sessions to discuss the work in the anthology with the critique writers. Additionally, students are encouraged to attend Creative Writing workshops on a variety of subjects led by the visiting writers. As a complement to school districts’ regular English classes, the Somerset County Teen Arts Creative Writing component offers students the opportunity to work directly with professional writers and poets who encourage them to fine-tune their writing skills while offering helpful hints into the creative process. The Somerset County Cultural & Heritage Commission wishes to commend the students whose work appears in the anthology, and hopes the experience will inspire them to continue writing as an expressive art form. Cover Artwork: Shaniyah Phinn, 17 Bound Brook High School Grade 11 2 SCHOOLS & STUDENTS ALEXANDER BATCHO INTERMEDIATE SCHOOL Teachers: Maggie Balzano, Ericka Barney, Kevin McManus Arias, Esteban .......................................................................................................................................................................... -

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie 2015 T 01

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie Reihe T Musiktonträgerverzeichnis Monatliches Verzeichnis Jahrgang: 2015 T 01 Stand: 21. Januar 2015 Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main) 2015 ISSN 1613-8945 urn:nbn:de:101-ReiheT01_2015-9 2 Hinweise Die Deutsche Nationalbibliografie erfasst eingesandte Pflichtexemplare in Deutschland veröffentlichter Medienwerke, aber auch im Ausland veröffentlichte deutschsprachige Medienwerke, Übersetzungen deutschsprachiger Medienwerke in andere Sprachen und fremdsprachige Medienwerke über Deutschland im Original. Grundlage für die Anzeige ist das Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG) vom 22. Juni 2006 (BGBl. I, S. 1338). Monografien und Periodika (Zeitschriften, zeitschriftenartige Reihen und Loseblattausgaben) werden in ihren unterschiedlichen Erscheinungsformen (z.B. Papierausgabe, Mikroform, Diaserie, AV-Medium, elektronische Offline-Publikationen, Arbeitstransparentsammlung oder Tonträger) angezeigt. Alle verzeichneten Titel enthalten einen Link zur Anzeige im Portalkatalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek und alle vorhandenen URLs z.B. von Inhaltsverzeichnissen sind als Link hinterlegt. Die Titelanzeigen der Musiktonträger in Reihe T sind, wie sche Katalogisierung von Ausgaben musikalischer Wer- auf der Sachgruppenübersicht angegeben, entsprechend ke (RAK-Musik)“ unter Einbeziehung der „International der Dewey-Dezimalklassifikation (DDC) gegliedert, wo- Standard Bibliographic Description for Printed Music – bei tiefere Ebenen mit bis zu sechs Stellen berücksichtigt ISBD (PM)“ zugrunde. -

Albus Dumbledore Concerns Would Be Something of an Understatement

Harry Potter and the Elder Sect The Beginning The Great Hall was silent other than the chanting of the young woman, her hands raised toward the stone ceiling. Her chanting ebbed and flowed with the pulse of the magic that came from the three ley lines that all three of her companions could feel. The woman began to glow with a blue aura and a burst of blood red energy leaped from her upraised hands to feather against the unyielding stone. The column of magic pulsed in time with the woman's chant, building with each stanza until she reached the end of her casting, and all the occupants in the room were blinded by the final pulse. "Bloody hell!" the largest of the observers breathed as he stared at the ceiling, which now displayed the sunlit sky of the summer day, complete with the clouds scudding across the ceiling. "Bloody hell is right," the other man said staring upward in amazement. "I thought you were going to make windows to let light in, not... that." "That's our Rowena," the plump woman said admiringly. "Even her windows stand out above all others." "Oh dear," the caster said, covering her mouth with her left hand. "I certainly didn't intend to do that." "Congratulations!" a new voice broke in, "You've invented magical glass Clara, you must be proud." The two men were instantly on guard, wands drawn, offensive spells on their lips, only to find themselves and Helga frozen in place. "Endora?" Rowena asked. "What are you doing here?" "I'm here to invite you to my wedding Clara, that's what Sisters do, you know," a redheaded woman emerged from the shadows.