Chapter 1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nigeria Centre for Disease Control Protecting the Health of Nigerians

Nigeria Centre for Disease Control Protecting the health of Nigerians Cholera hotspots mapping in Nigeria Iliya Cheshi - NCDC [email protected] Profile: Nigeria • Nigeria is a federal republic comprising 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja • Inhabited by more than 250 ethnic groups with over 500 distinct languages • Nigeria is divided roughly in half between Christians and Muslims 195.9 million (2018) Census 2 NIGERIA CENTRE FOR DISEASE CONTROL Introduction • Cholera remains a global public health problem, disproportionately affecting the tropical and sub-tropical areas of the world, where focal areas or hotspots play a key role in perpetuating the disease transmission • Targeting these hotspots with proven interventions e.g. Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WaSH), as well as Oral Cholera Vaccines (OCV) could reduce the mean annual incidence of the entire sub-Saharan African region by half (Lessler et al) • The Global Task Force on Cholera Control (GTFCC) has thus advocated for a comprehensive cholera control strategy where the use of OCV plays a complementary role to other preventive interventions, chiefly, ensuring access to WaSH 3 NIGERIA CENTRE FOR DISEASE CONTROL • To align its cholera control strategies with the global road map of the GTFCC, the team at the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) released a document detailing their preparedness and response plans • Assessing cholera transmission dynamics in Nigeria and identifying cholera hotspots were outlined as immediate-term goals. This help to design and implement relevant long term and cost effective solutions to achieve the ultimate goal of cholera elimination 4 NIGERIA CENTRE FOR DISEASE CONTROL Cholera hotspot mapping in Nigeria “Cholera hotspot” is defined as a geographically limited area (e.g. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Analysis of Spatial Variation in Agricultural Development Programmes in Kano State, Nigeria

ISSN (Print): 2476-8316 ISSN (Online): 2635-3490 Dutse Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences (DUJOPAS), Vol. 4 No. 2 December 2018 Analysis of Spatial Variation in Agricultural Development Programmes In Kano State, Nigeria Abdulkadir, H¹*; Adefila, J. O²; & Yusuf, R. O.2 ¹Department of Geography, Saadatu Rimi College of Education, Kano State, Nigeria. [email protected] 2 Department of Geography and Environmental Management, Ahmadu Bello University Zaria, Nigeria Abstract Agriculture is an important sector in the economic development and poverty alleviation drive of many countries. The importance of this sector is more pronounced in developing countries such as Nigeria. The persistent failure of agricultural development programmes in Nigeria has demonstrated the weakness of the policies coupled with inability of the successive administrations to resolve the fundamental problems of development. The major goal of this study is to analyse spatial variation in agricultural development programmes in Kano State. Questionnaire survey and documented materials constituted major sources of data. Twelve Local Government Areas were purposely selected across the three Senatorial districts. A total of 384 respondents were randomly selected in the administration of the questionnaire. Descriptive statistics was used to summarize the data. Also, inferential statistics such as the location quotient (LQ) was employed to measure level of variations in agricultural development programmes. The location quotient result is categorized into upper, middle and bottom based on the performance of each Local Government Area in agricultural development programmes The upper group include Tofa(0.80), Madobi(1.10), Warawa(1.20) and Kura (1.30) While the middle group include Gwarzo(1.34), Gaya (1.39), Danbatta(1.40) and Tsanyawa(1.45). -

Nigeria: Current Locations of Internally Displaced Persons from Borno State (As of 30 April 2016)

Nigeria: Current locations of internally displaced persons from Borno state (as of 30 April 2016) 1.8 million NIGER Estimated number of people displaced from Borno state. (Source DTM Round IX and Joint UN Mission) Yusufari CHAD Machina Nguru Estimated number of internally displaced persons Karasuwa per Local Government Areas of origin* Bade Gubio Bama Bade Geidam 405,507 Kaura-Namoda Gwoza 250,772 Talata Makoda Dambatta Jakusko BORNO Mafara Konduga 157,802 Bungudu Bichi YOBE Tarmua Magumeri Damboa 126,104 Ungogo Gabasawa Maru Gezawa Zaki Gamawa Ngala 114,155 Gummi Tofa Ajingi Jere Mafa Tsafe Gwale Warawa Itas/Gadau Kabo Maiduguri Gubio 98,891 Nangere Fune Damaturu ZAMFARA Karaye Madobi WudilGaya Kaga Jama'are Katagum Potiskum 94,004 Bunkure Dawakin Kudu Damban Kaga Kiru Konduga Mafa 77,692 Gusau Rogo Kibiya Takali Shira Maru Giade Misau Kukawa 63,317 Markafi KANO Sumaila Hawul Ikara Darazo 53,054 Sabon-Gari Warji Nafada Damboa Monguno 45,173 Zaria Ningi Marte 41,291 Soba Kubau Doguwa Biu Chibok Madagali Dikwa 37,408 Igabi Ganjuwa Dukku Askira/Uba Askira/Uba 24,958 Kaduna North Michika Kwami Kwaya Maiduguri 9,296 Kaduna South BAUCHI Hawul Kirfi BayoKusar Hong Mubi North Jere 5,490 Kauru Gombe Yamaltu Chikun Bauchi Abadam 4,524 /Deba Shani Gombi Mubi South Bassa Akko Mobbar KADUNA Dass 4,286 Jos North GOMBE Alkaleri Magumeri 2,000 Zango-Kataf Tafawa-Balewa Billiri BalangaGuyuk Song Maiha Biu 895 Jos South Shomgom ADAMAWA CHAD Chibok Lamurde 861 Kagarko PLATEAU Kwaya/Kusar 181 Kanke Numan Gireri Bwari Yola South Guzamala 68 Bokkos Karin-Lamido -

Analysis of Human Capital Development Index in Kano State

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Developing Country Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-607X (Paper) ISSN 2225-0565 (Online) Vol.7, No.5, 2017 Analysis of Human Capital Development Index in Kano State Dr. Nazifi Abdullahi Darma 1 Aigbedion I. Marvelous 1 Nafiu Bashir 2 Umar Abubakar kari 3 1.Department of Economics, University of Abuja 2.Department of Economics, Bayaro University Kano (BUK) 3.Department of Sociology, University of Abuja Abstract The study focuses on the analysis of human capital development index domesticated in Kano state, Nigeria. The main objective of this study is design human capital index and explores the contributors and inhibitors to the development and deployment of a healthy, educated and productive labour force in the state. The study covers the 44 local government areas and 122 wards of the State. Four key indicators were used for the design of human capital index in Kano State which are; level of education, health and wellness, workforce and employment and enabling environment. These indicators were analyzed using standardization method of ranking. From the index, some regions of the states have impressive and fair human capital index which are Northern Central, Eastern and North Western regions while some regions have poor ranking of human capital index in the State especially Far South, Western and Southern regions were most of the index were negative as per the defined indicators as captured by the level of education, health and wellness, workforce and employment and enabling environment. -

Preliminary Results from Direct-To-Facility Vaccine Deliveries in Kano, Nigeria

Preliminary results from direct-to-facility vaccine deliveries in Kano, Nigeria Muyi Aina Uchenna Igbokwe Solina Center for International Development and Research Rabiu Fagge Kano State Primary Health Care Management Board Presentation at the Health and Humanitarian Logistics Conference, Copenhagen June 8, 2017 CONFIDENTIAL AND PROPRIETARY Any use of this material without specific permission of Solina Health is strictly prohibited Content Background Methods Results Learnings Conclusion 2 General information on Kano state, Nigeria Kano at a glance Kano State has 44 LGAs ▪ 11 Million (2011) Population1 Makoda Kunchi Dambatta GDP per ▪ $1,288 USD Tsanyawa Bichi 2 Minjibir Gabasawa capita Dawakin Tofa Bagwai Ungogo Tofa Dala Gezawa Shanono Rimin Gado Tarauni Ajingi KumbotsoWarawa ▪ 0.44 Million Gwarzo Kabo No. of Madobi Dawakin Kudu Kura Gaya children <1 Wudil Karaye Bumkure Albasu Kiru Garun Mallam Garko Rogo Bebeji Rano ▪ 50 deaths per 1,000 Kibiya Takai Infant mortality rate3 children Tudun Wada Sumaila ▪ BCG: 27.5% Immun. ▪ DPT3: 18.9% coverage rate4 Doguwa ▪ Fully immunised: 13.2% ▪ 1,300 PHCs;, 1,142 0 50 100 Km Healthcare facilities providing RI services SOURCE: 1. City population statistics; 2. Canback Dangtel C-GIDD, 3. MDG 2014; 4. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey, 2013 3 Historically, a weak vaccine supply chain system significantly contributed to poor immunization coverage rates in Kano Key supply chain bottlenecks resulted in …and contributed to the poor vaccination inadequate supply of vaccine for RI sessions… coverage in Kano and other northern states DPT3 coverage by state (NDHS 2013) 1 Inadequate cold chain and poor maintenance limiting vaccine availability at service points 2 Complex and ineffective distribution architecture causing frequent stock outs 3 Inadequate and ad-hoc funding for vaccine transportation across all levels 4 Faulty vaccine forecasting and allocation which did not adequately reflect demand 5 Weak data management systems resulting in ineffective management decision making 6 Lack of proper supportive supervision due to 1. -

RJOAS, 6(114), June 2021

RJOAS, 6(114), June 2021 DOI 10.18551/rjoas.2021-06.03 EFFORTS OF DRY-LAND FARMERS OF KANO-NIGERIA IN THE CONDITIONS OF COVID-19 PANDEMIC THAT HITS GLOBAL FOOD SECURITY Salami Azeez Oyeniyi Shelterbelt Research Station, Forestry Research Institute of Nigeria, Kano, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] ORCID: 0000 0002 8250 0898 ABSTRACT A survey was conducted in Kano State-Nigeria aimed at exploring the travails of the dry-land farmers of the state amidst Covid-19 pandemic lockdown. The exercise was carried out in 8 Local Government Areas marked out in two sampling units within the metropolis and outside the metropolis. Within the Kano metropolis were Nassarawa, Ungogo, Tarauni and Dala; while Madobi, Minjiibir, Garun Mallam and Dambatta were outside the metropolitan. The enumeration thus pointed to the complete halt of all activities in the state during the ill-fated lockdown which was coupled with hunger, starvation, alongside stringent survival strategies; difficult access to agricultural imputes aids; and the effects on farming activities, among others. Structured interview was employed with a total of 120 respondents, using Availability Sampling Technique. However, food insecurity and malnutrition in Nigeria is as a result of the non implementation of the national and conventional food policy and agricultural programs. Nonetheless, in this critical time of economic pressure and the insurgence of Covid-19 pandemic, it is very important therefore to improve the budget allocation to the agricultural sector, as well as sustainable agricultural policy improvement programs by giving very compelling priority for nutrition on the agenda of the government, and enforcing a vibrant policy at aiding these dry-land farmers from whom the bulk of the global food production emanates. -

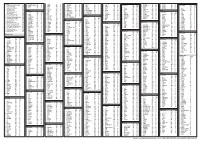

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST -

Nigeria Hotspots Location by State Platform Cholera Kano State West and Central Africa

Cholera - Nigeria hotspots location by state Platform Cholera Kano State West and Central Africa Kunchi Dambatta Makoda Katsina Kunchi Dambatta Makoda Tsanyawa Tsanyawa Bichi Bichi Jigawa Gabasawa Bagwai Minjibir Minjibir Gabasawa Dawakin Tofa Ungogo Shanono Bagwai Tofa Hotspots typology in the State Shanono Ungongo Gezawa Jigawa Tofa DalaFagge Hotspot type T.1: Rimin Gado Nassarawa GwaleTarauni Ajingi High priority area with a high frequency Gwarzo Rimin Gado Ajingi Kumbotso Warawa and a long duration. Gwarzo Kabo Gaya Kabo Kumbotso Wudil Karaye Madobi Madobi Dawakin Kudu Hotspot type T.2: Kura Gaya Medium priority area with a moderate frequency Karaye Kura Wudil Kiru Bunkure Bebeji Albasu and a long duration Garko Garum MallamBunkure Takai Kiru Albasu Rogo Rano Hotspots distribution in the State Nigeria Kibiya Garko Sumaila Rogo Bebeji Kibiya Rano Takai Sumaila 18 10 Tudun Wada Tudun Wada Hotspots Type 1 Hotspots Type 2 Bagwai Kano Municipal Bebeji Kura Bichi Karaye Garko Madobi Dala Kumbotso Dambatta Nassarawa Garum Mallam Minjibir Dawakin Tofa Rimin Gado Fagge Rogo Gaya Sumaila Gezawa Tarauni Kabo Wudil Bauchi Gwale Tsanyawa Gwarzo Ungongo Doguwa Legend Kaduna Ririwai Countries State Main roads XXX LGA (Local Governmental Area) Hydrography 0 70 140 280 420 560 XXX Cities (State capital, LGA capital, and other towns) Kilometers Date of production: January 21, 2016 Source: Ministries of Health of the countries members of the Cholera platform Contact : Cholera project - UNICEF West and Central Africa Regionial Office (WCARO) Feedback : Coordination : Julie Gauthier | [email protected] Information management : Alca Kuvituanga | [email protected] : of support the With The epidemiological data is certified and shared by national authorities towards the cholera platform members. -

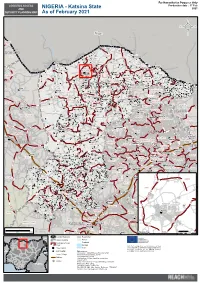

Katsina State 2021 SECURITY PLANNING MAP As of February 2021

For Humanitarian Purposes Only LOGISTICS ACCESS Production date : 17 Feb AND NIGERIA - Katsina State 2021 SECURITY PLANNING MAP As of February 2021 Niger SABON BIRNI Dutsin Bamli Forest* Dan Kunama Dan Kabba SOKOTO Forest Re Dagura Dadin Sarki ISA Matsai Maiaduwa KAITA Washemi Jibiya MAI'ADUA Jasai Kaita MASHI Mazanya Jerdedi Forest Zango Rese* Daura JIBIA Karawa Gulbin Baure KATSINA Forest* Zandam, Gulbi ZANGO Katsina Mashi Sandamu DAURA Forest Dan Tambara Fiwuni Kututure SHINKAFI Katsina Damakola Rese* Gurjiya Kigo, River Sandamu DUTSI Sukanawa MANI Unguwar GajeUnguwar Gaje Batagarawa Kaurin Saidu Pakarawa Forest* Maikiliya Dan Aunai SANDAMU Yantuba Dutsawa Lemo Tamdamwa Dutsawa Sabon Gari Fulani Giginya Nat* Forest Gidan Adamu Burudu Gargarawa Rese* Saboa Dandogo Rimi Mani Forest* Maibara Rimi Baure DancaleDancale Dutsi Kufani Adalawa Salei BATSARI Kawari Bardaya Zakata Dutsi BAURE Zurmi Gwiwa Kyaras ZURMI Yan Molo Batsari Alumu RIMI BINDAWA YANKWASHI Inga Dole GWIWA Musari Ungua Tsamia Tuwaru Sabuwa Dan KuliyaDan Gagi Daura Kuraye Yankwashi Kwahi Bagadi Safana Kabura Gawaji Kuma Faru Tachiawa Kurfi Yanuku Charanchi Roni Kazaure Ajiwa Bindawa Ingawa KURFI CHARANCHI Dandi Lake Gaiwa KAURA Dan Jakko Dambuna KAZAURE INGAWA Ruruma Birci NAMODA Kirkini Yakassa Jobe BABURA Gamda RONI Birni Mogaji Kankiya Gaci Kunchi MAKODA SAFANA Daddare Eaguwa Forest Rese JIGAWA Kusada BIRNIN MAGAJI Dutsin Ma KUSADA Dambatta Kafarda KUNCHI Safana KANKIA Makoda DAMBATTA GARKI Magwai, River Ungwan Adar Duru Ganuwa Dan-Tudu Makanwashi Karaduwa Jigawar Sawai -

An Account of the High Population in Kano State, Northern Nigeria

1 An Account of the High Population in Kano State, Northern Nigeria By Aliyu Salisu Barau Department of geography Federal College of Education, Kano, Nigeria PMB 3045 Kano [email protected] Introduction Population is one of the four fundamental features of a state, the other three being territory, sovereignty and government. By and large, population is an important factor in the global as well as local politics, economy and ecology. Indeed, population related issues are nowadays in the forefront of development activities/issues. The principal objectives of this paper is to reveal the following: • The nature and origin of population development in Kano State • The socio- cultural impulses for the maintained high population concentration in Kano State • The prospects for the sustained population growth in Kano state and • To objectively inform compatriots, expatriates and professionals about the peculiar nature of the population of Kano state. • To highlight some of the ecological risks associated with the population pressure stress in the state To achieve these objectives, relevant literature were reviewed and some observations and surveys were made in an attempt to drive home some facts and figures on the character and trends of the population of Kano state. 2 Population Development Theories Myriad demographic theories were developed overtime and over places to explain the arguments for or against population expansion. Prominent amongst such include those theories of Adam Smith who was vehemently optimistic of the need for population growth to sustain the emerging industrial muscle of Europe in the 19th century. Thomas Robert Malthus (in the 19th century too) was pessimistic of exploding population when the commensurate food supply was not in sight. -

Technical Cooperation for Development Planning on the One

The Federal Republic of Nigeria Small and Medium Enterprises Development Agency of Nigeria (SMEDAN) Technical Cooperation for Development Planning on the One Local Government One Product Programme for Revitalising the Rural Economy in the Federal Republic of Nigeria FINAL REPORT December 2011 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) IC Net Limited Overseas Merchandise Inspection Co., Ltd. Yachiyo Engineering Co., Ltd. A2 Kano State Katsina State A9 Jigawa State Kunchi MakodaDambatta A9 Tsanyawa A9 Nigeria all area Bichi Minjibir Gabasawa Bagwai DawakinT Ungogo Shanono A2 Gezawa Tofa Dala RiminGad Ajingi Lake Chad Gwarzo Kumbotso Warawa Sokoto Lake Chad Kabo A2 Madobi DawakinKK a n o S t a t e Karaye Kura Gaya Kano NdjamenaNdjamena Wudil Maiduguri Garum Mallam Bunkure A2 Albasu Kiru Garko Kaduna Rogo Bebeji Kaduna Rano Kibiya Takai A2 AbujaAbuja A2 Sumaila Tundun Wada Ilorin A126 IbadanIbadan A2 LagosLagos A236 Enugu PortoPorto NovoNovo Benin City Doguwa A11 ¯ A11 Port Harcourt Yaounde A11 A11 Douala 0Malabo75 150 300 450 600 750 Kaduna State A11 Km A236 A235 0 10 20 40 60 80 100 A236 Km A126 A1 Zamfara State Kebbi State Kebbi State Rijau A1 A2 Agwara A1 Kaduna State A125 Mariga Kaduna State A125 Niger State A235 A125 Magama Kontogur A2 Borgu A125 A2 Rafi A125 Shiroro Niger State Niger State Mashegu Legend A1 Muya Wushishi p Airports Chanchaga A7 Bosso Primary road A2 Paikoro Local road Lavun A124 A2A124 Katcha Gurara Urban Areas Mokwa Gbako Tafa A124 Suleja A234 Intermittent stream A7 Bida A124 Perennial stream A7 Kwara State Edati Agaie Water bodies: Intermittent A1 Lavun A2 Water bodies: Perennial A1 A7 Lapai National Boundary O y o S t a t e A1 State Boundary A123 A1 Niger and Kano State Nassarawa State 0 10 20 40 60 80 A123100 Km A123 LGA Boundary K o g i S t a t e Source: ESRI Japan; Study Team Map of Nigeria iii Table of contents Abbreviations and acronyms ...............................................................................................................