The Te Pahi Medal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kerikeri Mission House Conservation Plan

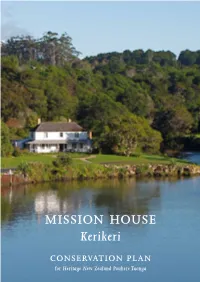

MISSION HOUSE Kerikeri CONSERVATION PLAN i for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Mission House Kerikeri CONSERVATION PLAN This Conservation Plan was formally adopted by the HNZPT Board 10 August 2017 under section 19 of the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 2014. Report Prepared by CHRIS COCHRAN MNZM, B Arch, FNZIA CONSERVATION ARCHITECT 20 Glenbervie Terrace, Wellington, New Zealand Phone 04-472 8847 Email ccc@clear. net. nz for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Northern Regional Office Premier Buildings 2 Durham Street East AUCKLAND 1010 FINAL 28 July 2017 Deed for the sale of land to the Church Missionary Society, 1819. Hocken Collections, University of Otago, 233a Front cover photo: Kerikeri Mission House, 2009 Back cover photo, detail of James Kemp’s tool chest, held in the house, 2009. ISBN 978–1–877563–29–4 (0nline) Contents PROLOGUES iv 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Commission 1 1.2 Ownership and Heritage Status 1 1.3 Acknowledgements 2 2.0 HISTORY 3 2.1 History of the Mission House 3 2.2 The Mission House 23 2.3 Chronology 33 2.4 Sources 37 3.0 DESCRIPTION 42 3.1 The Site 42 3.2 Description of the House Today 43 4.0 SIGNIFICANCE 46 4.1 Statement of Significance 46 4.2 Inventory 49 5.0 INFLUENCES ON CONSERVATION 93 5.1 Heritage New Zealand’s Objectives 93 5.2 Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 93 5.3 Resource Management Act 95 5.4 World Heritage Site 97 5.5 Building Act 98 5.6 Appropriate Standards 102 6.0 POLICIES 104 6.1 Background 104 6.2 Policies 107 6.3 Building Implications of the Policies 112 APPENDIX I 113 Icomos New Zealand Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Heritage Value APPENDIX II 121 Measured Drawings Prologue The Kerikeri Mission Station, nestled within an ancestral landscape of Ngāpuhi, is the remnant of an invitation by Hongi Hika to Samuel Marsden and Missionaries, thus strengthening the relationship between Ngāpuhi and Pākeha. -

Suitcases and Stories Pre-Federation Migration

SUITCASES AND STORIES PRE-FEDERATION MIGRATION These activity ideas are linked to groups of people who came to Australia before 1901, from convicts who had no choice, to the gold rush fortune seekers and free settlers who came to for a better life. To Research: Not all the convicts who came to Australia were from England. They originated from more than twenty-five countries. Make a list of where they came from. What is emancipation and how did it work? Consider and discuss the class distinction between the officers and free settlers, emancipated persons and convicts, and indigenous people. Research the life, work and achievements of Caroline Chisholm. Find out about quarantine stations. Where were they located? Why were the migrants put into quarantine? What diseases were the authorities worried about? What were the conditions like? How long was the average stay? To Create: A love token was a coin-sized piece of metal featuring an inscription. When someone was leaving for a long time they gave it to a loved one as a keepsake. Put yourself in the place of a convict being transported to Australia and create your own love token. Who would you be creating the token for? Love Token: Convict love token 1770s-1820s, 1770s-1820s (00040473) ANMM Collection. Thomas Barrett – The Charlotte Medal https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W7LvWKkZR70 List the crimes of Thomas Barrett before he arrived in Australia. Where was it thought, that Thomas Barrett learned his skills as an engraver? Who asked Thomas Barrett to create the Charlotte Medal? What did Thomas Barrett do to bring about his untimely ending? https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/thomas-barrett-the-man-who-carved-the-charlotte- medal-was-the-first-convict-executed-in-sydney/news-story/f425a72b34736f268f596966bee882c2 http://firstfleet.uow.edu.au/details.aspx?surname=&gender=&term=&ship=Charlotte&age=¬ es=&-recid=39 https://www.sea.museum/2013/11/26/reflections-on-charlotte-medal/ Play the voyage game The Voyage is an online game based on real convict voyages. -

Colonisation and the Involution of the Maori Economy Hazel Petrie

Colonisation and the Involution of the Maori Economy Hazel Petrie University of Auckland Auckland, New Zealand [email protected] A paper for Session 24 XIII World Congress of Economic History Buenos Aires July 2002 In 2001, international research by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, found Maori to be the most entrepreneurial people in the world, noting also that Maori ‘played an important role in the history and evolution of New Zealand entrepreneurship’.1 These findings beg a consideration of why the Maori economy, which was expanding vigorously in terms of value and in terms of international markets immediately prior to New Zealand’s annexation by Britain in 1840, involuted soon after colonisation. Before offering examples of Maori commercial practice in the period between initial European contact and colonisation, this paper will summarise some essential features of Maori society that underlay those practices. It will then consider how three broad aspects of the subsequent colonising process impacted on these practices during its first twenty five years. These aspects are: Christian beliefs and values, the ideologies of the newly emerging ‘science’ of Political Economy; and the racial attitudes and political demands of an increasingly powerful settler government. It is acknowledged that the nature of Maori commerce varied according to regional resources, the timing and degree of exposure to foreigners, local politics, individual personalities, and many other factors. There was no one Maori practice or experience, but the examples offered, which arose in a study of Maori flourmill and trading ship ownership, are intended to show how these facets of colonisation interwove to encourage a narrowing and contraction of Maori commercial endeavours. -

Download All About Islands

13 Motukokako Marsden Rangihoua Bird Rock ‘Hole in the rock’ Heritage Cross 12 DOC a 6 l u Park Cape Brett Hut s n Lighthouse i n R e a P n g a ih u o r ua e B T r ay e u P Deep Water P u Cove n Te Pahi a 11 I Islands n l e t Okahu Waewaetorea HMZS Canterbury 10 Wreck Dive k l a W 7 9 t t e 4 km r B Moturoa e Black Motukiekie p Urupukapuka a Rocks C y 8 Rawhiti a B e k O Moturua Otehei Bay a o r Motuarohia Brett Walk o 5 pe T Ca e T 4 / u r u m u o m rb angamu a Ha h m g W u u T n um ra a c h m Tapeka Point k a W ng ha Waitangi W Mountain Bike Park Long Beach Waitangi Treaty Grounds 14 Did you know? RUSSELL Project Island Song is a wildlife sanctuary. The Waitangi seven main islands in the eastern Bay of Islands 3 Pompallier have been pest mammal free since 2009, and the Mission Haruru natural eco-systems are being restored. Falls www.projectislandsong.co.nz 2 To Helena Bay / Whangarei PAIHIA 1 5 Point of interest Passenger ferry Scenic views Food NORTHLAND NZ To Kaikohe / Kerikeri / Kerikeri Kaikohe To Tohu Whenua Water taxi Iconic photo stop! Cafe Kaitaia Swimming Tour boat Local favourite Shop Okiato Whangarei Snorkeling Mountain biking Don’t miss Private boat Opua Forest et e Inl aikar Walking track Petrol station EV Charging Camping Opua Car Ferry W Find more at northlandjourneys.co.nz 2019 © Northland Inc. -

Australian National Maritime Museum Annual Report 2013–14 Australian National Maritime Museum Annual Report 2013–14 2013–14 Chairman’S Message

AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2013–14 AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2013–14 2013–14 CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE Australian National Maritime Museum It’s my pleasure, once again, to present the Australian National Annual Report 2013–14 © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 Maritime Museum’s Annual Report for the period 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2014. This Annual Report addresses the second year of the ISSN 1034-5019 museum’s strategic plan for the period 2012–2015, a key planning This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under document that was developed and tabled in accordance with the the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior permission from the Australian Australian National Maritime Museum Act 1990. National Maritime Museum. AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM This was another year of change and progress for the museum, for both its staff The Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM) and its site. Various factors and events – the important centenary of the beginning at Darling Harbour, Sydney, opens 9.30 am–5 pm every day (9.30 am–6 pm in January). Closed 25 December. of World War 1, the upcoming anniversary of Gallipoli, and the exhibitions, projects and events the museum has programmed in commemoration; major staffing ENTRY AT 30 JUNE 2014 Big Ticket: admission to galleries and exhibitions + vessels changes; the extensive redevelopment of the Darling Harbour area; and the more + Kids on Deck long-term plans for the redevelopment of the museum – have all ensured that it Adult $27, child $16, concession/pensioners $16 Members/child under 4 free, family $70 has been a busy and challenging year. -

Maori in Sydney and the Critical Role They Played in the Success of the Town Has Been Minimised by Historians

Sydney Journal 3(1) December 2010 ISSN 1835-0151 http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ojs/index.php/sydney_journal/index Maori Jo Kamira Non-Indigenous written history claims there was no contact between Maori and Koori.1 Despite this, Indigenous lore in Australia tells of contact between the two. In the early days of the colony, trans-Tasman travel was fluid between Sydney and New Zealand for Maori and non-Indigenous people alike. An eighteenth-century map by Daniel Djurberg shows an alternative name for New Holland as 'Ulimaroa'. This was widely believed to be a Maori word for Australia; however there is no L in the Maori alphabet. This may mean it was a Polynesian word, perhaps Hawaiian or Samoan, however it does not explain how the name came into Djurberg's possession. From 1788 to 1840 the colony of New South Wales included New Zealand. The head of state was the monarch, represented by the governor of New South Wales. British sovereignty over New Zealand was not established until 1840, when the Treaty of Waitangi recognised that New Zealand had been an independent territory until then. The Declaration of Independence signed in 1835 by a number of Maori chiefs and formally recognised by the British government indicated that British sovereignty did not extend to New Zealand. This meant the British in Sydney had no option than to deal with Maori, who were still in control of their own land. The history of Maori in Sydney and the critical role they played in the success of the town has been minimised by historians. -

Here Were Two Million Copies of the Dairyman’S Daughter Pub- Lished in English, in the USA As Well As in the UK

A major new biography of the leading evangelist to New Zealand, the ‘flogging parson’ Rev. Samuel Marsden, and the struggles with ‘the world, the flesh and the devil’ that he spent his life pursuing. New Zealanders know Samuel Marsden as the founder of the CMS missions that brought Christianity (and perhaps sheep) to New Zealand. Australians know him as ‘the flogging parson’ who established large landholdings and was dismissed from his position as magistrate for exceeding his jurisdiction. English readers know of Marsden for his key role in the history of missions and empire. In this major biography spanning research, and the subject’s life, across England, New South Wales and New Zealand, Andrew Sharp tells the story of Marsden’s life from the inside. Sharp focuses on revealing to modern readers the powerful evangelical lens through which Marsden understood the world. By diving deeply into key moments – the voyage out, the disputes with Macquarie, the founding of missions – Sharp gets us to reimagine the world as Marsden saw it: always under threat from the Prince of Darkness, in need of ‘a bold reprover of vice’, a world written in the words of the King James Bible. Andrew Sharp takes us back into the nineteenth-century world, and an evangelical mind, to reveal the past as truly a foreign country. Andrew Sharp is Emeritus Professor of Political Studies at the University of Auckland. Since 2006 he has lived in London, and is the author or editor of books including The Political Ideas of the English Civil Wars (1983), Justice and the Māori (1990, expanded 1997), Leap into the Dark: The Changing Role of the State in New Zealand since 1984 (1994), The English Levellers (1998), Histories Power and Loss: Uses of the Past – a New Zealand Commentary (2001 with P. -

Australian National Maritime Museum Annual Report 2019–20 Contents

Australian National Maritime Museum Annual Report 2019–20 Contents Publication information 1 Chairman’s letter of transmittal 3 Director’s statement 6 Our vision, mission and priorities 7 Year in review 8 Highlights 8 Grants received 8 Director’s report 9 Director’s highlight 11 Annual Performance Statement 13 Introductory statement 13 Purpose of the museum 13 Results for 2019–20 14 Delivery against Statement of Intent 37 Exhibitions and attractions 44 Touring exhibitions 48 Multimedia 50 Governance and accountability 52 Corporate governance 52 Roles and functions of the museum 53 Legislation 55 Outcome and program structure 56 ANMM Council 56 Council meetings and committees 62 Legal and compliance 65 People and culture 67 Other information 73 Grants programs 79 Australian National Maritime Museum Foundation 87 Financial Statements 2019–2020 91 Appendixes 130 Index 168 Annual Report 2019–20 Publication information 1 Publication information Copyright Australian National Maritime Museum Annual Report 2019–20 © Commonwealth of Australia 2020 ISSN 1039-4036 (print) ISSN 2204-678X (online) This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior permission from the Australian National Maritime Museum. Australian National Maritime Museum The Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM) at Darling Harbour, Sydney, opens 9.30 am–5 pm every day (9.30 am–6 pm in January). Closed 25 December. Entry at 30 June 2020 See it All Ticket Adult $25, child $15, concession $20, family $60 (2 adults + 3 children), child under 4 free. Entry includes: ● Special exhibitions – Wildlife Photographer of the Year and Sea Monsters: Prehistoric ocean predators ● Top-deck vessel tours aboard HMB Endeavour and HMAS Vampire ● Permanent galleries – Under Southern Skies; Cook and the Pacific; HERE: Kupe to Cook Big Ticket (1/7/19–4/12/19) Adult $32, child $20, concession $20, family $79 (2 adults + 3 children), child under 4 free. -

Admiral Arthur Phillip.Pdf

Admiral Arthur Phillip, R.N. (1738 – 1814) A brief story by Angus Ross for the Bread Street Ward Club, 2019 One of the famous people born in Bread Street was Admiral Arthur Phillip, R.N, the Founder of Australia and first Governor of New South Wales (1788-1792). His is a fascinating story that only recently has become a major subject of research, especially around his naval exploits, but also his impact in the New Forest where he lived mid-career and also around Bath, where he finally settled and died. I have studied records from the time Phillip sailed to Australia, a work published at the end of the 19c and finally from more recent research. Some events are reported differently by different observes or researchers so I have taken the most likely record for this story. Arthur Phillip in later life His Statue in Watling Street, City of London I have tried to balance the amount of detail without ending up with too long a story. It is important to understand the pre-First Fleet Phillip to best understand how he was chosen and was so well qualified and experienced to undertake the journey and to establish the colony. So, from a range of accounts written in various times, this story aims to identify the important elements of Phillip’s development ending in his success in taking out that First Fleet, made up primarily of convicts and marines, to start the first settlement. I have concluded this story with something about the period after he returned from Australia and what recognition of his life and achievements are available to see today. -

Ohakiri Pa St Paul's Rock Scenic Reserve Historic Heritage

Ohakiri Pa St Paul’s Rock Scenic Reserve Historic Heritage Assessment Melina Goddard 2011 Ohakiri Pa: St Paul’s Rock Scenic Reserve Historic Heritage Assessment Melina Goddard, DoC, Bay of Islands Area Office 2011 Cover image: Ohakiri pa/St Paul’s Rock taken facing south (A. Blanshard DoC) Aerial of St Paul’s Rock/Ohakiri pa. Peer-reviewed by: Joan Maingay, Andrew Blanshard Publication information © Copyright New Zealand Department of Conservation (web pdf # needed) 2 Contents Site Overview 5 History Description 5 Fabric Description 10 Cultural Connections 12 National Context 12 Historic Significance 13 Fabric Significance 13 Cultural Significance 13 Management Recommendations 13 Management Documentation 14 Management Chronology 14 Sources 16 Endnotes 17 Image: Entrance to the Whangaroa Harbour taken facing northeast from the top of the Dukes Nose (K. Upperton DoC). 3 Figure 1: The location of Ohakiri Pa in the St Paul’s Rock Reserve, Whang aroa Harbour, indicated in inset. Site Overview Ohakiri Pa or St Paul’s Rock, as it is better known as today, is located within the St Paul’s Rock Scenic Reserve which is under the care of the Department of Conservation. The Reserve consists of two blocks, the northern and southern, on a peninsula that projects out into the Whangaroa Harbour on Northland’s east coast (fig 1). The rock is part of the Maori legend that tells of the formation of the harbour and today it is a significant landmark within the district and commands the inner harbour. Ohakiri is regionally significant as one of the only accessible tangible remains of Whangaroa’s early Maori and European history. -

Historic Heritage Area Historic Heritage Area Nrc Id 15 1

HISTORIC HERITAGE AREA NRC ID 151515 PART ONEONE:: IDENTIFICATION Place Name: RANGIHOUA HISTORIC AREA Image ::: Copyright: Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Site Address: Lying at the southern end of the Purerua Peninsula, the area incorporates the whole of Rangihoua Bay, the eastern end of Wairoa Bay and a cluster of small islands (collectively known as the Te Pahi Islands), which lie offshore between the two bays and the seabed in the northern parts of Rangihoua and Wairoa Bays. It forms a contiguous area measuring approximately 2000m east-west x 2500m north-south. Legal Description: The registration includes all of the land in each of: Te Pahi Islands SO 57149 (NZ Gazette 1981, p.728), North Auckland Land District; Island of Motu Apo Blk IX Kerikeri SD (CT NA767/279); Lot 4 DP 361786 (CT 251357), North Auckland Land District; Lot 42 DP 361786 (CT 251364), North Auckland Land District; Lot 3 DP 202151 and Lot 5 DP 202152 (CT 251366), North Auckland Land District; Lots 4 and 6 DP 202152 (CT NA130C/641) North Auckland Land District; Lot 3 DP 361786 (CT 251356), North Auckland Land District; Lot 40 DP 361786 (CT 251362), North Auckland Land District; Lot 41 DP 361786 (CT 251363), North Auckland Land District; Lot 1 DP 361786 (CT 251354), North Auckland Land District; Lot 28 DP 346421 (CT 190767), North Auckland Land District; Lot 31 DP 323083 (CT 103501), North Auckland Land District; Lot 40 DP 346421 (CT 190761), North Auckland Land District; Rangihoua Native Reserve ML 12693 (MLC Title Order Reference 12 BI 19), North Auckland Land -

FFF Board Taken to Court! "'-~-~~ - =------'

PATRON: Her Excellency, Professor Marie Bashir, AC, CVO, Governor of New South Wales Volume 39, Issue 5 September/October 2008 TO LIVE ON IN TiiE HEARTS AND MINDS OF DESCENDANTS IS NEVER TO DIE FFF Board taken to Court! "'-~-~~ - =------ ' ' his gathering was caught unaware in front of the Old 1999. The restored building now operates as an Environment TCourt House in Wollongong. The occasion in June was and Heritage Centre, and is owned by Council. the visit of the Fellowship Board, for its first meeting ever John went on to conduct a brief tour of some inner city in "regional territory", that of the South Coast Chapter. The heritage sites including the plaque designating the founding of meeting was preceded by a social gathering with Chapter the lllawarra by Surveyor General Oxley in 1816, the plaque members and friends during which Peter Christian gave to Charles Throsby Smith, founder of Wollongong, the rotunda an intricate, yet whimsiqil-~ccount of the history of the Fel recording the centenary of the landing of the first Europeans lowship. The hosts were iavish in their provision of morning in the district, Bass and Flinders in 1796, and the excellent tea and the local deli excelled itself,with the luncheon fare. atmospheric lllawarra Museum. Chapter President, John Boyd, was proud to show off the The Board Meeting was the first occasion when the three building. It was designed by Alexander Dawson as the Gong's newly-appointed members, Keith Thomas, Robin Palmer and Courthouse from 1858 to 1885. It then became in turn the Ron Withington were all in attendance.