Chapter Two Mapping the Celluloid Journey of the Queer This Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume-13-Skipper-1568-Songs.Pdf

HINDI 1568 Song No. Song Name Singer Album Song In 14131 Aa Aa Bhi Ja Lata Mangeshkar Tesri Kasam Volume-6 14039 Aa Dance Karen Thora Romance AshaKare Bhonsle Mohammed Rafi Khandan Volume-5 14208 Aa Ha Haa Naino Ke Kishore Kumar Hamaare Tumhare Volume-3 14040 Aa Hosh Mein Sun Suresh Wadkar Vidhaata Volume-9 14041 Aa Ja Meri Jaan Kishore Kumar Asha Bhonsle Jawab Volume-3 14042 Aa Ja Re Aa Ja Kishore Kumar Asha Bhonsle Ankh Micholi Volume-3 13615 Aa Mere Humjoli Aa Lata Mangeshkar Mohammed RafJeene Ki Raah Volume-6 13616 Aa Meri Jaan Lata Mangeshkar Chandni Volume-6 12605 Aa Mohabbat Ki Basti BasayengeKishore Kumar Lata MangeshkarFareb Volume-3 13617 Aadmi Zindagi Mohd Aziz Vishwatma Volume-9 14209 Aage Se Dekho Peechhe Se Kishore Kumar Amit Kumar Ghazab Volume-3 14344 Aah Ko Chahiye Ghulam Ali Rooh E Ghazal Ghulam AliVolume-12 14132 Aah Ko Chajiye Jagjit Singh Mirza Ghalib Volume-9 13618 Aai Baharon Ki Sham Mohammed Rafi Wapas Volume-4 14133 Aai Karke Singaar Lata Mangeshkar Do Anjaane Volume-6 13619 Aaina Hai Mera Chehra Lata Mangeshkar Asha Bhonsle SuAaina Volume-6 13620 Aaina Mujhse Meri Talat Aziz Suraj Sanim Daddy Volume-9 14506 Aaiye Barishon Ka Mausam Pankaj Udhas Chandi Jaisa Rang Hai TeraVolume-12 14043 Aaiye Huzoor Aaiye Na Asha Bhonsle Karmayogi Volume-5 14345 Aaj Ek Ajnabi Se Ashok Khosla Mulaqat Ashok Khosla Volume-12 14346 Aaj Hum Bichade Hai Jagjit Singh Love Is Blind Volume-12 12404 Aaj Is Darja Pila Do Ki Mohammed Rafi Vaasana Volume-4 14436 Aaj Kal Shauqe Deedar Hai Asha Bhosle Mohammed Rafi Leader Volume-5 14044 Aaj -

Shu Lea Cheang with Alexandra Juhasz

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Brooklyn College 2020 When Are You Going to Catch Up with Me? Shu Lea Cheang with Alexandra Juhasz Alexandra Juhasz CUNY Brooklyn College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/bc_pubs/272 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 When Are You Going to Catch Up with Me? Shu Lea Cheang with Alexandra Juhasz Abstract: “Digital nomad” Shu Lea Cheang and friend and critic Alexandra Juhasz consider the reasons for and implications of the censorship of Cheang’s 2017 film FLUIDØ, particularly as it connects to their shared concerns in AIDS activism, feminism, pornography, and queer media. They consider changing norms, politics, and film practices in relation to technology and the body. They debate how we might know, and what we might need, from feminist-queer pornography given feminist-queer engagements with our bodies and ever more common cyborgian existences. Their informal chat opens a window onto the interconnections and adaptations that live between friends, sex, technology, illness, feminism, and representation. Keywords: cyberpunk, digital media, feminist porn, Shu Lea Cheang, queer and AIDS media Shu Lea Cheang is a self-described “digital nomad.” Her multimedia practice engages the many people, ideas, politics, and forms that are raised and enlivened by her peripatetic, digital, fluid existence. Ruby Rich described her 2000 feature I.K.U. -

Yaari Dosti: Young Men Redefine Masculinity a Training Manual

A ‘real man’…….. l is not Gud (feminine; homosexual) l Y has sex only with women aari Dost l leads the physical fighting l always needs to prove that he is a real Young Men Redefine i man. — Y Masculinity oung Men Redefine Masculinity OR l establishes relationship based on equity, intimacy and respect rather than sexual conquest l takes responsibility towards partner and provides care to children l shares responsibility for sexual and reproductive health is- sues with partner l does not support or use violence against partners Adapted from Programme H—Working with Young Men Series Yaari-Dosti-English 1 8/28/06 3:06:27 PM Yaari Dosti: Young Men Redefine Masculinity A Training Manual Population Council, New Delhi CORO for Literacy, Mumbai MAMTA, New Delhi Instituto Promundo, Rio de Janerio Programme H Alliance Yaari Dosti is an adaptation of Program H: Working with Young Men Series, originally developed by Instituto Promundo, ECOS (Brazil), Instituto PAPAI (Brazil) and Salud y Genero (Mexico). In India the adaptation was compiled and produced by Population Council, CORO (Mumbai) and other collaborative partners. This training manual aims to promote gender equity and addresses masculinity as a strategy for the prevention of HIV infection. The Manual is based on operations research that was undertaken in Mumbai and Uttar Pradesh to develop educational activities targeted to young men. For additional copies of this manual, please contact: Population Council 142, Golf Links New Delhi 110003 Tel: +91 11 41743410-11 Fax: +91 11 41743412 Email : [email protected] Website: www.popcouncil.org/horizons South & East Asia Regional Office Zone 5A, India Habitat Centre Lodi Road New Delhi 110003 Tel: +91 11 24642901/02 Fax: +91 11 24642903 Email: [email protected] The Population Council, an international, nonprofit, nongovernmental organization, seeks to improve the well-being and reproductive health of current and future generations around the world and to help achieve a humane, equitable, and sustainable balance between people and resources. -

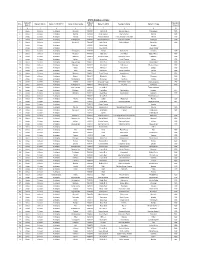

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A SPRAKASH REDDY 25 A D REGIMENT C/O 56 APO AMBALA CANTT 133001 0000IN30047642435822 22.50 2 A THYAGRAJ 19 JAYA CHEDANAGAR CHEMBUR MUMBAI 400089 0000000000VQA0017773 135.00 3 A SRINIVAS FLAT NO 305 BUILDING NO 30 VSNL STAFF QTRS OSHIWARA JOGESHWARI MUMBAI 400102 0000IN30047641828243 1,800.00 4 A PURUSHOTHAM C/O SREE KRISHNA MURTY & SON MEDICAL STORES 9 10 32 D S TEMPLE STREET WARANGAL AP 506002 0000IN30102220028476 90.00 5 A VASUNDHARA 29-19-70 II FLR DORNAKAL ROAD VIJAYAWADA 520002 0000000000VQA0034395 405.00 6 A H SRINIVAS H NO 2-220, NEAR S B H, MADHURANAGAR, KAKINADA, 533004 0000IN30226910944446 112.50 7 A R BASHEER D. NO. 10-24-1038 JUMMA MASJID ROAD, BUNDER MANGALORE 575001 0000000000VQA0032687 135.00 8 A NATARAJAN ANUGRAHA 9 SUBADRAL STREET TRIPLICANE CHENNAI 600005 0000000000VQA0042317 135.00 9 A GAYATHRI BHASKARAAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041978 135.00 10 A VATSALA BHASKARAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041977 135.00 11 A DHEENADAYALAN 14 AND 15 BALASUBRAMANI STREET GAJAVINAYAGA CITY, VENKATAPURAM CHENNAI, TAMILNADU 600053 0000IN30154914678295 1,350.00 12 A AYINAN NO 34 JEEVANANDAM STREET VINAYAKAPURAM AMBATTUR CHENNAI 600053 0000000000VQA0042517 135.00 13 A RAJASHANMUGA SUNDARAM NO 5 THELUNGU STREET ORATHANADU POST AND TK THANJAVUR 614625 0000IN30177414782892 180.00 14 A PALANICHAMY 1 / 28B ANNA COLONY KONAR CHATRAM MALLIYAMPATTU POST TRICHY 620102 0000IN30108022454737 112.50 15 A Vasanthi W/o G -

Special Events: Film and Television Programme

Left to right: Show Me Love, Gas Food Lodging, My Own Private Idaho, Do the Right Thing Wednesday 12 June 2019, London. Throughout July and August BFI Southbank will host a two month exploration of explosive, transformative and challenging cinema and TV made from 1989-1999 – the 1990s broke all the rules and kick-started the careers of some of the most celebrated filmmakers working today, from Quentin Tarantino and Richard Linklater to Gurinder Chadha and Takeshi Kitano. NINETIES: YOUNG SOUL REBELS will explore work that dared to be different, bold and exciting filmmaking that had a profound effect on pop culture and everyday life. The influence of these titles can still be felt today – from the explosive energy of Do the Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989) through to the transformative style of The Blair Witch Project (1999) and The Matrix (The Wachowskis, 1999). Special events during the season will include a 90s film quiz, an event celebrating classic 90s children’s TV, black cinema throughout the decade and the world cinema that made waves. Special guests attending for Q&As and introductions will include Isaac Julien (Young Soul Rebels), Russell T Davies (Queer as Folk) and Amy Jenkins (This Life). SPECIAL EVENTS: - The season will kick off with a special screening Do the Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989) on Friday 5 July, presented in partnership with We Are Parable; Spike Lee’s astute, funny and moving film stars out with a spat in an Italian restaurant in Brooklyn, before things escalate to a tragic event taking place in the neighbourhood. -

The Iafor Journal of Media, Communication & Film

the iafor journal of media, communication & film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Editor: James Rowlins ISSN: 2187-0667 The IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue – I IAFOR Publications Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane The International Academic Forum IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Editor: James Rowlins, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore Associate Editor: Celia Lam, University of Notre Dame Australia, Australia Assistant Editor: Anna Krivoruchko, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore Advisory Editor: Jecheol Park, National University of Singapore, Singapore Published by The International Academic Forum (IAFOR), Japan Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane Editorial Assistance: Rachel Dyer IAFOR Publications. Sakae 1-16-26-201, Naka-ward, Aichi, Japan 460-0008 IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 IAFOR Publications © Copyright 2016 ISSN: 2187-0667 Online: JOMCF.iafor.org Cover photograph: Harajuku, James Rowlins IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Edited by James Rowlins Table of Contents Notes on Contributors 1 Introduction 3 Editor, James Rowlins Interview with Martin Wood: A Filmmaker’s Journey into Research 5 Questions by James Rowlins Theorizing Subjectivity and Community Through Film 15 Jakub Morawski Sinophone Queerness and Female Auteurship in Zero Chou’s Drifting Flowers 22 Zoran Lee Pecic On Using Machinima as “Found” in Animation Production 36 Jifeng Huang A Story in the Making: Storytelling in the Digital Marketing of 53 Independent Films Nico Meissner Film Festivals and Cinematic Events Bridging the Gap between the Individual 63 and the Community: Cinema and Social Function in Conflict Resolution Elisa Costa Villaverde Semiotic Approach to Media Language 77 Michael Ejstrup and Bjarne le Fevre Jakobsen Revitalising Indigenous Resistance and Dissent through Online Media 90 Elizabeth Burrows IAFOR Journal of Media, Communicaion & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Notes on Contributors Dr. -

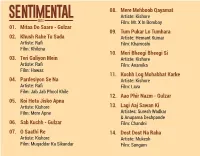

Sentimental Booklet for Web Copy

08. Mere Mehboob Qayamat Artiste: Kishore Film: Mr. X In Bombay 01. Mitaa Do Saare - Gulzar 09. Tum Pukar Lo Tumhara 02. Khush Rahe Tu Sada Artiste: Hemant Kumar Artiste: Rafi Film: Khamoshi Film: Khilona 10. Meri Bheegi Bheegi Si 03. Teri Galiyon Mein Artiste: Kishore Artiste: Rafi Film: Anamika Film: Hawas 11. Kuchh Log Mohabbat Karke 04. Pardesiyon Se Na Artiste: Kishore Artiste: Rafi Film: Lava Film: Jab Jab Phool Khile 12. Aao Phir Nazm - Gulzar 05. Koi Hota Jisko Apna Artiste: Kishore 13. Lagi Aaj Sawan Ki Film: Mere Apne Artistes: Suresh Wadkar & Anupama Deshpande 06. Sab Kuchh - Gulzar Film: Chandni 07. O Saathi Re 14. Dost Dost Na Raha Artiste: Kishore Artiste: Mukesh Film: Muqaddar Ka Sikandar Film: Sangam 2 3 15. Hui Sham Unka Khayal 22. Din Dhal Jaye Haye Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Rafi Film: Mere Hamdam Mere Dost Film: Guide 01. Mitaa Do Saare - Gulzar 16. Kuchh To Log Kahenge 23. Mere Toote Huye Dil Se 02. Khush Rahe Tu Sada Artiste: Kishore Artiste: Mukesh Artiste: Rafi Film: Amar Prem Film: Chhalia Film: Khilona 17. Waqt Karta Jo Wafa 24. Hue Hum Jinke Liye 03. Teri Galiyon Mein Artiste: Mukesh Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Rafi Film: Dil Ne Pukara Film: Deedar Film: Hawas 18. Patthar Ke Sanam 25. Koi Sagar Dil Ko Bahlata 04. Pardesiyon Se Na Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Rafi Film: Patthar Ke Sanam Film: Dil Diya Dard Liya Film: Jab Jab Phool Khile 19. Khilona Jan Kar Tum To 26. Chandi Ki Deewar 05. Koi Hota Jisko Apna Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Mukesh Artiste: Kishore Film: Khilona Film: Vishwas Film: Mere Apne 20. -

New Queer Cinema, a 25-Film Series Commemorating the 20Th Anniversary of the Watershed Year for New Queer Cinema, Oct 9 & 11—16

BAMcinématek presents Born in Flames: New Queer Cinema, a 25-film series commemorating the 20th anniversary of the watershed year for New Queer Cinema, Oct 9 & 11—16 The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Brooklyn, NY/Sep 14, 2012—From Tuesday, October 9 through Tuesday, October 16, BAMcinématek presents Born in Flames: New Queer Cinema, a series commemorating the 20th anniversary of the term ―New Queer Cinema‖ and coinciding with LGBT History Month. A loosely defined subset of the independent film zeitgeist of the early 1990s, New Queer Cinema saw a number of openly gay artists break out with films that vented anger over homophobic policies of the Reagan and Thatcher governments and the grim realities of the AIDS epidemic with aesthetically and politically radical images of gay life. This primer of new queer classics includes more than two dozen LGBT-themed features and short films, including important early works by directors Todd Haynes, Gus Van Sant, and Gregg Araki, and experimental filmmakers Peggy Ahwesh, Luther Price, and Isaac Julien. New Queer Cinema was first named and defined 20 years ago in a brief but influential article in Sight & Sound by critic B. Ruby Rich, who noted a confluence of gay-oriented films among the most acclaimed entries in the Sundance, Toronto, and New Directors/New Films festivals of 1991 and 1992. Rich called it ―Homo Pomo,‖ a self-aware style defined by ―appropriation and pastiche, irony, as well as a reworking of history with social constructionism very much in mind . irreverent, energetic, alternately minimalist and excessive.‖ The most prominent of the films Rich catalogued were Tom Kalin’s Leopold and Loeb story Swoon (the subject of a 20th anniversary BAMcinématek tribute on September 13) and Haynes’ Sundance Grand Jury Prize winner Poison (1991—Oct 12), an unpolished but complex triptych of unrelated, stylistically diverse, Jean Genet-inspired stories. -

Films 2018.Xlsx

List of feature films certified in 2018 Certified Type Of Film Certificate No. Title Language Certificate No. Certificate Date Duration/Le (Video/Digita Producer Name Production House Type ngth l/Celluloid) ARABIC ARABIC WITH 1 LITTLE GANDHI VFL/1/68/2018-MUM 13 June 2018 91.38 Video HOUSE OF FILM - U ENGLISH SUBTITLE Assamese SVF 1 AMAZON ADVENTURE Assamese DIL/2/5/2018-KOL 02 January 2018 140 Digital Ravi Sharma ENTERTAINMENT UA PVT. LTD. TRILOKINATH India Stories Media XHOIXOBOTE 2 Assamese DIL/2/20/2018-MUM 18 January 2018 93.04 Digital CHANDRABHAN & Entertainment Pvt UA DHEMALITE. MALHOTRA Ltd AM TELEVISION 3 LILAR PORA LEILALOI Assamese DIL/2/1/2018-GUW 30 January 2018 97.09 Digital Sanjive Narain UA PVT LTD. A.R. 4 NIJANOR GAAN Assamese DIL/1/1/2018-GUW 12 March 2018 155.1 Digital Haider Alam Azad U INTERNATIONAL Ravindra Singh ANHAD STUDIO 5 RAKTABEEZ Assamese DIL/2/3/2018-GUW 08 May 2018 127.23 Digital UA Rajawat PVT.LTD. ASSAMESE WITH Gopendra Mohan SHIVAM 6 KAANEEN DIL/1/3/2018-GUW 09 May 2018 135 Digital U ENGLISH SUBTITLES Das CREATION Ankita Das 7 TANDAB OF PANDAB Assamese DIL/1/4/2018-GUW 15 May 2018 150.41 Digital Arian Entertainment U Choudhury 8 KRODH Assamese DIL/3/1/2018-GUW 25 May 2018 100.36 Digital Manoj Baishya - A Ajay Vishnu Children's Film 9 HAPPY MOTHER'S DAY Assamese DIL/1/5/2018-GUW 08 June 2018 108.08 Digital U Chavan Society, India Ajay Vishnu Children's Film 10 GILLI GILLI ATTA Assamese DIL/1/6/2018-GUW 08 June 2018 85.17 Digital U Chavan Society, India SEEMA- THE UNTOLD ASSAMESE WITH AM TELEVISION 11 DIL/1/17/2018-GUW 25 June 2018 94.1 Digital Sanjive Narain U STORY ENGLISH SUBTITLES PVT LTD. -

ASHA Database Unnao Name of ID No.Of Population S.No

ASHA Database Unnao Name Of ID No.of Population S.No. Name Of Block Name Of CHC/BPHC Name Of Sub-Centre Name Of ASHA Husband's Name Name Of Village District ASHA Covered 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 Unnao C.Karan Achalganj Kharauli 7406001 Anita Devi Shravan Kumar Chandanpur 1000 2 Unnao C.Karan Achalganj Banthar 7406002 Anita Gautam Manoj Kumar Banthar 1000 3 Unnao C.Karan Achalganj Banthar 7406003 Anita Kushwaha Prem Shankar Kushwaha Banthar 1000 4 Unnao C.Karan Achalganj Achalganj Ist 7406004 Anita Shriwastava Ramesh Chandra Achalganj 1200 5 Unnao C.Karan Achalganj Maswasi II 7406005 Anita Singh Mukesh Singh Galgalaha 1000 6 Unnao C.Karan Achalganj 7406006 Anita Singh Singaha 7 Unnao C.Karan Achalganj 7406007 Anju Mishra Gayatri Nagar 8 Unnao C.Karan Achalganj Kulhagarha 7406008 Antoni Ram Kumar Khutaha 1800 9 Unnao C.Karan Achalganj Maswasi 7406009 Anuradha Anil Tiwari Durgan Khera 1500 10 Unnao C.Karan Achalganj Badarka 7406010 Archana Yadav Mratunjay Kumar Badarka 1590 11 Unnao C.Karan Achalganj Kathar 7406011 Aruna Devi Lotan Sharma Kathar 1000 12 Unnao C.Karan Achalganj Jagjeewanpur 7406012 Asha Devi Fool Singh Yadav Manoharpur 1000 13 Unnao C.Karan Achalganj Dubepur 7406013 Asha Devi Kalicharan Bhaisai Chatur 850 14 Unnao C.Karan Achalganj Band 7406014 Asha Devi Muneshwar Saidpur 1300 15 Unnao C.Karan Achalganj Nibai 7406015 Beena Devi Dinesh Chandra Baruwa 1000 16 Unnao C.Karan Achalganj Mainaha 7406016 Beenu Rawat Arvind Kumar Tikauli 2000 17 Unnao C.Karan Achalganj Supasi 7406017 Bhagirathi Dulare Ramganj 1000 18 Unnao C.Karan Achalganj -

Title: New Gay Sincerity' and Andrew Haigh's Weekend (UK, 2011)

1 Title: New Gay Sincerity’ and Andrew Haigh’s Weekend (UK, 2011) Author: Andrew Moor Contact Details: Department of English, Manchester Metropolitan University [email protected] Biography: Andrew Moor is Reader in Cinema History at Manchester Metropolitan University. He is the author of Powell and Pressburger: A Cinema of Magic Spaces (IB Tauris, 2005) and co-editor of The Cinema of Michael Powell: International Perspectives on an English Film-maker (BFI) and Signs of Life: Medicine and Cinema (Wallflower Press, 2005). He has written widely on aspects of Queer and British cinema. Acknowledgements: Sue Harper and Andy Medhurst kindly read early drafts of this article, and provided useful comments. Their input was gratefully received and is happily acknowledged. 2 ‘New Gay Sincerity’ and Andrew Haigh’s Weekend In the last few years an important new aesthetic direction for non-straight cinema has emerged. A handful of films have chosen a mode of frank, observational realism, capturing the everyday lives of gay people in ways that ‘feel’ authentic but which are far from naïve about the image-making process. Adapting Jim Collins’s concept of ‘New Sincerity’, this article proposes that the new trend in gay cinema can be thought of as a mode of ‘New Gay Sincerity’.1 Collins first coined his phrase to account for conservative genre-cinema in the late 1980s and early 1990s that had turned its back on forms of parody and self- reflexivity to present instead an ‘aura’ of authenticity. It signifies a tentative reaction against the polished irony and the proliferated textuality of postmodernism. -

Lesbians (On Screen) Were Not Meant to Survive

Lesbians (On Screen) Were not Meant to Survive Federica Fabbiani, Independent Scholar, Italy The European Conference on Media, Communication & Film 2017 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract My paper focuses on the evolution of the image of the lesbian on the screen. We all well know what can be the role of cinema in the structuring of the personal and collective imaginary and hence the importance of visual communication tools to share and spread lesbian stories "even" with a happy ending. If, in the first filmic productions, lesbians inevitably made a bad end, lately they are also able to live ‘happily ever after’. I do too believe that “cinema is the ultimate pervert art. It doesn't give you what you desire - it tells you how to desire” (Slavoy Žižek, 2006), that is to say that the lesbian spectator had for too long to operate a semantic reversal to overcome a performance deficit and to desire in the first instance only to be someone else, normal and normalized. And here it comes during the 2000s a commercial lesbian cinematography, addressed at a wider audience, which well interpret the actual trend, that most pleases the young audience (considering reliable likes and tweets on social networks) towards normality. It is still difficult to define precisely these trends: what would queer scholars say about this linear path toward a way of life that dares only to return to normality? No more eccentric, not abject, perhaps not even more lesbians, but 'only' women. Is this pseudo-normality (with fewer rights, protections, privileges) the new invisibility? Keywords: Lesbianism, Lesbian cinema, Queer cinema, LGBT, Lesbian iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org Introduction I would try to trace how the representation of lesbians on screen has developed over time.