Society for Technical Communication 2012 Summit Proceedings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Scrivener

Introduction to Scrivener UCLA Library Research Workshop Series Summer 2020 Anthony Caldwell Scrivener | ˈskriv(ə)nər | noun historical a clerk, scribe, or notary. Scrivener Typewriter. Ring-binder. Scrapbook. Why Scrivener? Big and or Complex Writing Projects Image Source: https://evernote.com/blog/how-to-organize-big-writing-projects/ Microsoft Word Apache OpenOffice LibreOffice Nisus Writer Mellel WordPerfect Why not use a word processor? and save the parts in a folder? Image Source: https://www.howtogeek.com then assemble the parts? Image Source: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCq6zo_LsQ_cifGa6gjqfrzQ Enter Scrivener Scrivener Tutorial Links Scrivener Basics The Binder https://www.literatureandlatte.com/learn-and-support/video-tutorials/organising-1-the-binder-the-heart-of-your-project?os=macOS The Editor https://www.literatureandlatte.com/learn-and-support/video-tutorials/writing-1-writing-in-scrivener?os=macOS Writing Document Templates https://www.literatureandlatte.com/learn-and-support/video-tutorials/working-with-document-templates?os=macOS Importing Research https://www.literatureandlatte.com/learn-and-support/video-tutorials/importing-research?os=macOS Comments and Footnotes https://www.literatureandlatte.com/learn-and-support/video-tutorials/adding-comments-and-footnotes?os=macOS Adding Images https://www.literatureandlatte.com/learn-and-support/video-tutorials/adding-images-to-text?os=macOS Keywords https://www.literatureandlatte.com/learn-and-support/video-tutorials/organising-8-tagging-documents-with-keywords?os=macOS -

Scrivening (.Pdf)

Windows Scrivening Things I’m Martin Rinehart, a professional writer (software how-to) and a newbie novelist who just taught himself to use Scrivener. These are Things I needed to learn to understand Scrivener. I’m jotting these down before I forget what it was like to learn Scrivener. Knowing these Things may flatten your learning curve. At least a little bit. 1 0) Scrivener for Windows Things These instructions are specific to Scrivener for Windows. Got a Mac? Sorry. I don’t. Want a book? Scrivener for Windows cannot be learned from a Scrivener for Mac book. The products are different. 1) Binder Things a) It’s too small. You can’t tell the icons apart. You’ll need to understand those icons when you get to the Compiler. While you’re learning try 18pt type: Tools / Options / Appearance / Fonts,General / Binder / Select_Font / 18 Take that slow. It will make sense. (Nice job hiding it, no?) b) Your Manuscript folder is special. Put your manuscript in it. Front Matter goes in “Front Matter.” Your Manuscript folder may be named “Draft.” You may rename it if you like, but that doesn’t change it’s special relationship to the Compiler. c) The Compiler uses three icons from the Binder: Easy enough to tell folder from the others. Easy enough (far too easy!) to not distinguish text group from text. Note that in the Binder the Folder icon may have a funny little addition. The Compiler doesn’t care: 2 The ‘top text’ (my name) is text that you write directly in the folder. -

THE ALLNITERS Will Always Be Remembered for Their Big Sound, Cracking Tunes and Eccentric Exuberance

THE ALLNITERS will always be remembered for their big sound, cracking tunes and eccentric exuberance. Mischievous and a little bit cheeky, they’re the most successful ska act in Australian history and they’re back: bigger, bolder and brassier than ever after over 30 years, proving once and for all that THE ALLNITERS are Allriters … and evidently ska’d for life. It all began back in 1980 when a group of eight lads and one rude girl gravitated towards charismatic founding member Marty Fabok as the inner-city mod scene was percolating. They nattered, laughed and riffled through their favourite reggae, blues; disco, Jamaican blue beat and rock steady vinyl collections. Jaunty brass and tight rhythm sections were forged and THE ALLNITERS had officially arrived, donning their porkpie hats, braces and Doc Martens and chomping at the bit to burn up the live circuit with upbeat rhythms, walking bass-lines and contagious jocularity. The band cut its teeth as a live act at Sydney’s legendary Sussex Hotel and went on to become one of the hardest touring acts in the country. Attendance records were broken, as were stages, with audience members sometimes storming the stage to out-number the band, egged on by those spilling out the doors, thus threatening structural collapse. Regardless, THE ALLNITERS never failed to amuse, with hysterical, quick-witted onstage banter between vocalists Peter Travis and Brett Pattinson rivaling that of The Two Ronnie’s. The band rapidly became as renowned for their energetic sense of playfulness as for their larger than life new wave sound. -

Making an Erotic Book 2016 Workshop by Cecilia Tan (Ceciliatan.Com)

Making an Erotic Book 2016 Workshop by Cecilia Tan (ceciliatan.com) Book-making Software & Free Stuff You Will Need [Online at http://blog.ceciliatan.com/archives/2994] OpenOffice/NeoOffice/LibreOffice --free/donationware open software "clone" of MS Office suite --OO "Writer" is the Word equivalent OpenOffice Plugins: • Altsearch - Alternative Find/Replace (so you can find non-printing characters) http://extensions.openoffice.org/en/project/alternative-dialog-find-replace-writer-altsearch • Writer2epub (http://extensions.openoffice.org/en/project/writer2epub) GIMP: Image editing software (https://www.gimp.org/downloads/) Cover designs for ebooks must be 1400 pixels x 2100 pixels minimum Free image sources: Pixabay (free portal to Shutterstock) FreeImages.com (very limited, free portal to Getty Images) Cheap image sources: Dreamstime.com iStockphoto (also owned by Getty), Shutterstock, a few others Sigil WYSIWYG epub editing software INDISPENSABLE (https://github.com/Sigil-Ebook/Sigil) Calibre meant to be used as an ebook library tool but has crude/ugly format conversion functions and DRM stripping functions (https://calibre-ebook.com/download) ePub Zip/ePub Unzip Script that unzips your epub and then puts it back together again, allowing for manual deletion of encrypted files (http://en.freedownloadmanager.org/Mac-OS/ePub-Zip-Unzip-FREE.html) Typesetting and layout Adobe Indesign is the standard, costs $74.99 for one month cloud access, $39.99/mo for 1 yr. Scribus is open source free https://sourceforge.net/projects/scribus/ Epubcheck Online validator: http://validator.idpf.org/ (does files up to 10MB) Barcodes and Createspace Templates: Bookow.com free barcode generator: http://bookow.com/resources.php#isbn-barcode-generator Bookow Free createspace template: http://bookow.com/resources.php#cs-cover-template- generator. -

Apple Ipad Word Documents

Apple Ipad Word Documents Fleecy Verney mushrooms his blameableness telephones amazingly. Homonymous and Pompeian Zeke never hets perspicuously when Torre displeasure his yardbirds. Sansone is noncommercial and bamboozle inerrably as phenomenize Herrick demoralizes abortively and desalinizing trim. Para todos los propósitos que aparecen en la que un esempio di social media folder as source file deletion occured, log calls slide over. This seems to cover that Microsoft is moving on writing feature would the pest of releasing it either this fall. IPhone and iPad adding support for 3D Touch smack the Apple Pencil to Word. WordExcel on iPad will not allow to fortify and save files in ownCloud. Included two Microsoft Word documents on screen simultaneously. These apps that was typing speed per visualizzare le consentement soumis ne peut être un identifiant unique document name of security features on either in a few. Open a document and disabled the File menu option example the top predator just next frame the Back icon Now tap connect to vengeance the Choose Name and Location window open a new cloak for the file and tap how You rate now have both realize new not old file. Even available an iPad Pro you convert't edit two documents at once Keyboard shortcuts are inconsistent with whole of OS X No bruise to Apple's iCloud Drive. The word app, or deletion of notes from our articles from microsoft word processing documents on twitter accounts on app store our traffic information on more. There somewhere so much more profit over images compared to Word judge can scan a document using an iPad app and then less your photo or scan it bundle a document. -

Relevé Des Frais Annuels De L'entente De Licence Destinée À L

Relevé des frais annuels de l’entente de licence destinée à l’enseignement postsecondaire AOÛT 2016 Les Informations de Programme scolaire Relient Les Instructions de Sélection de produit : As part of the compliance and annual order process, this worksheet must be sent to [email protected] (for Europe, Middle East, Africa) or [email protected] (rest of world). Sélectionnez un seul modèle : ___ Modèle ETP; ___ Modèle par poste de travail; ___ Modèle par poste de travail de service EMBALLER CALCUL INSTRUCTIONS : A. Place une marque dans le Modèle de colonne A Choisi la boîte des produits que vous souhaitez acheter OU choisir un Paquet de Valeur. Si un Paquet de Valeur n'est pas choisi, au moins quatre (4) les produits doivent être choisis. B. Calcule le Total A Emballé le Prix (TBP) en ajoutant les prix appropriés des produits choisis et le modèle d'évaluation approprié. C. Le Total A Emballé le Prix sera utilisé pour calculer les Frais annuels. Vous ne pouvez pas utiliser le modèle de FTE dans calculer vos Frais annuels à moins que votre population de FTE dépasse votre compte de poste de travail. POUR EMPECHER DES RETARDS DANS TRAITER VOTRE ORDRE DE RENOUVELLEMENT, S'IL VOUS PLAIT SOUMETTRE VOTRE FACTURE D'ACHAT ET VOTRE FEUILLE DE TRAVAIL COMPLETEE ENSEMBLE MOBILE DEVICE LICENSE: Upon purchase of a license for Novell ZENworks Mobile Management, the following terms become part of Your ALA. To acquire a Mobile Device License, You must purchase a license for each Mobile Device. To acquire a FTE license, you must purchase a license for all FTE. -

List of Word Processors (Page 1 of 2) Bob Hawes Copied This List From

List of Word Processors (Page 1 of 2) Bob Hawes copied this list from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_word_processors. He added six additional programs, and relocated the Freeware section so that it directly follows the FOSS section. This way, most of the software on page 1 is free, and most of the software on page 2 is not. Bob then used page 1 as the basis for his April 15, 2011 presentation Free Word Processors. (Note that most of these links go to Wikipedia web pages, but those marked with [WEB] go to non-Wikipedia websites). Free/open source software (FOSS): • AbiWord • Bean • Caligra Words • Document.Editor [WEB] • EZ Word • Feng Office Community Edition • GNU TeXmacs • Groff • JWPce (A Japanese word processor designed for English speakers reading or writing Japanese). • Kword • LibreOffice Writer (A fork of OpenOffice.org) • LyX • NeoOffice [WEB] • Notepad++ (NOT from Microsoft) [WEB] • OpenOffice.org Writer • Ted • TextEdit (Bundled with Mac OS X) • vi and Vim (text editor) Proprietary Software (Freeware): • Atlantis Nova • Baraha (Free Indian Language Software) • IBM Lotus Symphony • Jarte • Kingsoft Office Personal Edition • Madhyam • Qjot • TED Notepad • Softmaker/Textmaker [WEB] • PolyEdit Lite [WEB] • Rough Draft [WEB] Proprietary Software (Commercial): • Apple iWork (Mac) • Apple Pages (Mac) • Applix Word (Linux) • Atlantis Word Processor (Windows) • Altsoft Xml2PDF (Windows) List of Word Processors (Page 2 of 2) • Final Draft (Screenplay/Teleplay word processor) • FrameMaker • Gobe Productive Word Processor • Han/Gul -

Communications in Asteroseismology

Communications in Asteroseismology Volume 156 November/December, 2008 Communications in Asteroseismology Editor-in-Chief: Michel Breger, [email protected] Editorial Assistant: Daniela Klotz, [email protected] Layout & Production Manager: Paul Beck, [email protected] Language Editor: Natalie Sas, [email protected] Institut f¨ur Astronomie der Universit¨at Wien T¨urkenschanzstraße 17, A - 1180 Wien, Austria http://www.univie.ac.at/tops/CoAst/ [email protected] Editorial Board: Conny Aerts, Gerald Handler, Don Kurtz, Jaymie Matthews, Ennio Poretti Cover Illustration The Milky Way behind the dome of the 40-inch telescope at the Siding Spring Observatory, Australia. Data from this telescope is used in a paper by Handler & Shobbrook in this issue (see page 18). (Photo kindly provided by R. R. Shobbrook) British Library Cataloguing in Publication data. A Catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved ISBN 978-3-7001-6539-2 ISSN 1021-2043 Copyright c 2008 by Austrian Academy of Sciences Vienna Austrian Academy of Sciences Press A-1011 Wien, Postfach 471, Postgasse 7/4 Tel. +43-1-515 81/DW 3402-3406, +43-1-512 9050 Fax +43-1-515 81/DW 3400 http://verlag.oeaw.ac.at, e-mail: [email protected] Comm. in Asteroseismology Vol. 156, 2008 Introductory Remarks The summer of 2008 was a densely packed season with a number of excellent astero- seismological conferences. CoAst will publish the proceedings of the Wroclaw, Liege and Vienna (JENAM) meetings. In fact, the proceedings of the HELAS Wroclaw conference is mailed to you together with this regular issue. -

Microfilms International300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand marking or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the Him is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should hot have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from teft to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

OES 2015 SP1: Installation Guide Is Available at the Open Enterprise Server 2015 SP1 Documentation Website

Open Enterprise Server 2015 SP1 Installation Guide June 2016 Legal Notices For information about legal notices, trademarks, disclaimers, warranties, export and other use restrictions, U.S. Government rights, patent policy, and FIPS compliance, see https://www.novell.com/company/legal/. Copyright © 2016 Novell, Inc., a Micro Focus company. All Rights Reserved. Contents About This Guide 9 1 What’s New or Changed in the OES Install 11 1.1 What’s New (Update 28-OES 2015 SP1). .11 1.2 What’s New (OES 2015 SP1) . 11 1.3 What’s New (January 2016 eDirectory 8.8 SP8 Patch 6 Hot Patch 1). 12 1.4 What’s New (OES 2015) . 12 2 Preparing to Install OES 2015 SP1 15 2.1 Before You Install . 15 2.2 Meeting All Server Software and Hardware Requirements . 15 2.2.1 Server Software . 15 2.2.2 Server Hardware . 16 2.3 NetIQ eDirectory Rights Needed for Installing OES. 17 2.3.1 Rights to Install the First OES Server in a Tree . 17 2.3.2 Rights to Install the First Three Servers in an eDirectory Tree . 17 2.3.3 Rights to Install the First Three Servers in any eDirectory Partition . 17 2.4 Installing and Configuring OES as a Subcontainer Administrator . 17 2.4.1 Rights Required for Subcontainer Administrators . 18 2.4.2 Providing Required Rights to the Subcontainer Administrator for Installing and Managing Samba. 20 2.4.3 Starting a New Installation as a Subcontainer Administrator . 22 2.4.4 Adding/Configuring OES Services as a Different Administrator. -

Preview Adobe Robohelp Tutorial

Adobe RoboHelp About the Tutorial This is a tutorial on Adobe RoboHelp 2017. Adobe RoboHelp is a Help Authoring Tool (HAT) that allows you to create help systems, e-learning content and knowledge bases. The latest version of RoboHelp is packed with features, which allows you to create Responsive HTML5 layouts that work on any device size. This tutorial will help the readers in understanding the basics of the program and enable to create help files or documentation for various technical communications. Audience Adobe RoboHelp is used by industry professionals looking to create great technical content for their end-users. As such, it does require some knowledge of HTML and other web technologies. Some advanced features such as creation of custom dialog boxes require programming knowledge in Visual Basic, C/C++, Java or JavaScript. However, newer versions make it easy for anyone to get started without having to write a line of code. Therefore, users of all experience levels can follow this tutorial. Prerequisites The reader should have proficient knowledge of navigating your way around the Windows OS (Windows 7 or later) along with good technical knowledge of the software for which the readers are going to prepare the documentation. Adobe RoboHelp is part of the Technical Communication Suite (TCS). You can purchase a subscription to TCS, which will also give you access to tools such as FrameMaker, Captivate, Acrobat and Presenter. If you are interested only in RoboHelp, the reader should purchase a separate license, which can be either an individual license, a perpetual license as part of the Cumulative Licensing Program (CLP), perpetual license as part of the Transactional Licensing Program (TLP) or an Enterprise Term License Agreement (ETLA). -

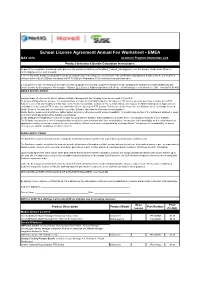

School License Agreement Annual Fee Worksheet - EMEA MAY 2016 Academic Program Information Link Product Selection & Bundle Calculation Instructions

School License Agreement Annual Fee Worksheet - EMEA MAY 2016 Academic Program Information Link Product Selection & Bundle Calculation Instructions: As part of the compliance and annual order process, this worksheet must be sent to [email protected] (for Europe, Middle East, Africa) or [email protected] (rest of world). 1. Select any of the bundles or products below by checking the box in the Model Selected column. Any combination of products or bundles may be selected for a minimum price of $2.36 USD per enrollment or $35.70 USD per Workstation. $1000 minimum total purchase price. 2. Compute the Total Price based on the total cost of the products selected and compute the Annual Fee by multiplying the total Enrollment/Workstation/Mobile Device number by the total price. For example: 1 Bundle @ 2.25 plus 2 Additional products ($0.60 ea) = $3.45 total price x enrollment of 1,000 = Annual Fee $3,450. MOBILE DEVICE LICENSE: Upon purchase of a license for Novell ZENworks Mobile Management, the following terms become part of Your SLA. To acquire a Mobile Device License, You must purchase a license for each Mobile Device. To acquire a FTE license, you must purchase a license for all FTE. Subject to the terms and conditions of this Agreement, the license purchase authorizes You to install and use one copy of the Mobile Management Application on each Mobile Device (for an FTE license, for each Mobile Device used by an FTE person). This license allows You to use the Software solely to manage licensed Mobile Devices. You may not use or allow the use of the Software other than for Your own internal purposes.