What Is New, and Permanent, About the "New Economy"?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA CHOICE-INTERSIL CIVIL ACTION MICROSYSTEMS, INC. et a1 Plaintiffs V. AGERE SYSTEMS, INC. Defendant NO. 02-8219 MEMORANDUM AND ORDER September 2003 McLaughlin , J. ,&, Choice-Intersil Microsystems, Inc., Intersil Corporation, and Intersil Americas Inc., have moved for a preliminary injunction on their claim of trade secret misappropriation under Pennsylvania law.' The plaintiffs own trade secrets related to computer technology as the successors in interest to a Joint Development Agreement ("JDA',) executed in 1995 between Digital Ocean and AT&T Corporation. The plaintiffs allege that Agere Systems, Inc. (\\Agere")unlawfully possesses and unlawfully disclosed the trade secrets. Agere claims that it possesses the trade secrets legally as a successor in interest under the JDA to Lucent Technologies that was a successor in interest to AT&T. - 1 For ease of reference, Choice-Intersil Microsystems, Inc. is referred to as I1Choice-Intersil,"Intersil Corporation is referred to as I1Intersil,"Intersil Americas Inc. is referred to as IIIntersil Americas,Ii and Choice Microsystems is referred to as llChoice. 1 The parties agreed to brief the plaintiffs’ motion in stages. At this stage, the parties briefed whether Agere has rights under the JDA and the Addendum to the JDA. The Court held an evidentiary hearing on this issue on February 27 and 28, 2003. The parties have consented to the Court issuing a final decision on whether Agere has rights under the JDA and the Addendum. The Court finds that Agere does have rights under the JDA and the Addendum. The question before the Court is whether the section of the JDA that granted to each party the right to assign its rights under the JDA to a successor in interest continued in existence in an Addendum to the JDA. -

OMB Number: Expires: Estimated Average Burden Hours Per Response

---------------------------- OMB APPROVAL ---------------------------- OMB Number: Expires: Estimated average burden hours per response..... ---------------------------- SEC USE ONLY ---------------------------- ---------------------------- UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 13F INFORMATION REQUIRED OF INSTITUTIONAL INVESTMENT MANAGERS PURSUANT TO SECTION 13(f) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 AND RULES THEREUNDER REPORT FOR THE CALENDAR YEAR OR QUARTER ENDED November 9, 2001 - -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- (PLEASE READ INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE PREPARING FORM.) - -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- IF AMENDED REPORT CHECK HERE: |_| Allstate Life Insurance Company - -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NAME OF INSTITUTIONAL INVESTMENT MANAGER 3075 Sanders Road, Suite G4A Northbrook Illinois 60062-7127 - -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- BUSINESS ADDRESS (STREET) (CITY) (STATE) (ZIP) Doug Welch (847) 402-2170 Assistant Vice President, Investment Operation - -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NAME, PHONE NO., AND TITLE OF PERSON DULY AUTHORIZED TO SUBMIT THIS REPORT. - ------------------------------------ATTENTION----------------------------------- INTENTIONAL MISSTATEMENTS OR OMISSIONS OF FACTS CONSTITUTE FEDERAL CRIMINAL VIOLATIONS. SEE 18 U.S.C. 1001 AND 15 U.S.C. -

The Rise and Demise of Lucent Technologies

The Rise and Demise of Lucent Technologies William Lazonick and Edward March In 1999, as the Internet boom was approaching its apex, Lucent Technologies was the world’s largest telecommunications equip- ment company. With revenues of $38.3 billion, net income of $4.8 billion, and 153,000 employees for the fiscal year ending Septem- ber 30, 1999, Lucent was larger and more profitable than Nortel, Alcatel, and Ericsson, its three major global competitors. In fiscal 2006, however, Lucent’s revenues were only $8.8 billion and its employment level stood at 29,800. Both figures were lower than those of its three major rivals. On December 1, 2006, the merger that created Alcatel-Lucent took place, making Lucent a wholly owned subsidiary of Alcatel. In this paper, we analyze the rise and demise of Lucent Technologies from the time that it was spun off from AT&T in April 1996 to its 2006 merger with Alcatel. Our analysis of the case of Lucent shows the ways in which strategy, The original version of this paper was presented to the conference on Innovation and Competition in the Global Communications Technology Industry, INSEAD, August 23-24, 2007. The paper is part of a project, emanating from that conference, engaged in a comparative, updatable analysis of business models and economic performance among the major competitors in the communications technology industry. For other studies generated by this project, see www.theAIRnet.org. In the later stages, funding was provided by FINNOV project through Theme 8 of the Seventh Framework Programme of the European Commission (Socio-Economic Sciences and Humanities), under the topic “The role of finance for growth, employment and competitiveness in Europe” (SSH- 2007-1.2-03), as well as by the Ford Foundation project on “Financial institutions for innovation and development” and the Institute for New Economic Thinking project on “The stock market and innovative enterprise.” We are grateful to Yue Zhang for research assistance. -

The History of Verizon Communications

The history of Verizon Communications Verizon Communications Inc., based in New York City and incorporated in Delaware, was formed on June 30, 2000, with the merger of Bell Atlantic Corp. and GTE Corp. Verizon began trading on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) under the VZ symbol on Monday, July 3, 2000. It also began trading on the NASDAQ exchange under the same symbol on March 10, 2010. The symbol was selected because it uses the two letters of the Verizon logo that graphically portray speed, while also echoing the origin of the company name: veritas, the Latin word connoting certainty and reliability, and horizon, signifying forward-looking and visionary. While Verizon is truly a 21st century company, the mergers that formed Verizon were many years in the making, involving companies with roots that can be traced to the beginnings of the telephone business in the late 19th century. Government regulation largely shaped the evolution of the industry throughout most of the 20th century. Then, with the signing of the Telecommunications Act on February 8, 1996, federal law directed a shift to more market-based policies. This promise of a new competitive marketplace was a driving force behind Verizon’s formation. Verizon’s formation The mergers that formed Verizon were among the largest in U.S. business history, culminating in a definitive merger agreement, dated July 27, 1998, between Bell Atlantic, based in New York City, and GTE, which was in the process of moving its headquarters from Stamford, Conn., to Irving, Texas. GTE and Bell Atlantic had each evolved and grown through years of mergers, acquisitions and divestitures. -

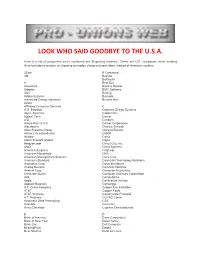

Look Who Said Goodbye to the U.S.A

LOOK WHO SAID GOODBYE TO THE U.S.A. Here is a list of companies we've confirmed are "Exporting America." These are U.S. companies either sending American jobs overseas, or choosing to employ cheap overseas labor, instead of American workers. 3Com B Continued… 3M Bechtel BellSouth A Best Buy Accenture Black & Decker Adaptec BMC Software ADC Boeing Adobe Systems Brocade Advanced Energy Industries Bumble Bee Aetna Affiliated Computer Services C A.G. Edwards Cadence Design Systems Agere Systems Capital One Agilent Tech. Carrier AIG Cendant Alamo Rent A Car Cerner Corporation Albertson's Charles Schwab Allen Systems Group ChevronTexaco Alliance Semiconductor CIBER Allstate Ciena Alpha Thought Global Cigna Amazon.com Circuit City, Inc. AMD Cisco Systems American Express Citigroup American Household CNA American Management Systems Coca-Cola American Standard Cognizant Technology Solutions Amphenol Corp. Columbia House Analog Devices Comcast Holdings Andrew Corp. Computer Associates Anheuser-Busch Computer Sciences Corporation AOL CompuServe Apple Continental Airlines Applied Materials Convergys A.T. Cross Company Cooper Tire & Rubber AT&T Cooper Tools AT&T Wireless Countrywide Financial A.T. Kearney COVAD Comm. Automatic Data Processing CSX Avanade Cummins Avery Dennison Cypress Semiconductor B D Bank of America Dana Corporation Bank of New York Delco Remy Bank One Dell Computer BearingPoint Delphi Bear Stearns Delta Air Lines D Continued…. H Continued…. Direct TV Humana Discover Document Sciences Corp. I Dow Chemical IBM Dun & Bradstreet iGate -

Telecommunication Basic Research: an Uncertain Future for the Bell Legacy

Telecommunication Basic Research: An Uncertain Future for the Bell Legacy A. Michael Noll Professor of Communications Annenberg School for Communication University of Southern California Los Angeles, CA 90089-0281 (213) 740-0926 February 14, 2003 Accepted for publication in Prometheus. An initial version of this paper was presented at the Telecommunications Policy Research Conference in Alexandria, Virginia on September 30, 2002. - 1 - Telecommunication Basic Research: An Uncertain Future for the Bell Legacy A. Michael Noll ABSTRACT The Bell Labs of decades ago was well recognized as a national treasure for its pioneering innovations and its creation of new knowledge. However, the breakup of the Bell System that occurred in 1984 resulted in considerable change for research and development in telecommunication. This paper reviews that history and, in anticipation of continuing uncertainty and a possible impending crisis, examines possible options for the future to assure leadership by the United States in basic research in telecommunication. KEYWORDS: research, Bell Labs, AT&T Labs, R&D, basic research, telecommunication research RESEARCH LEGACY A hundred years ago, the radio spectrum and telecommunication was developed by a number of pioneering inventors and businesses. Some of these pioneers were: Thomas Alva Edison, David Sarnoff, Nikola Tesla, Guglielmo Marconi, Samuel Finley Breese Morse, Lee de Forest (triode vacuum tube), Claude E. Shannon (information theory), Alexander Graham Bell, Allen DuMont, Philo T. Farnsworth (TV camera), Vladimir Kosma Zworykin (electronic television), Michael Pupin (loading coil), and Edwin Howard Armstrong (FM radio). Many of the businesses founded by these pioneers created their own corporate research laboratories to continue the tradition of invention. -

1 in the United States District Court for the District Of

Case 1:19-cv-02155-LPS Document 11 Filed 03/30/20 Page 1 of 56 PageID #: 108 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE BELL SEMICONDUCTOR, LLC, Plaintiff, Civil Action No. 19-cv-2155-LPS v. JURY TRIAL DEMANDED INTEGRATED DEVICE TECHNOLOGY, INC. Defendant. BELL SEMICONDUCTOR, LLC’S FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT Plaintiff Bell Semiconductor, LLC (“Bell Semic”) as and for its complaint against Integrated Device Technology, Inc. (“IDT” or “Defendant”) alleges as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. Bell Semic is a technology and intellectual property licensing company. Bell Semic’s patent portfolio comprises over 1,900 worldwide patents and applications, approximately 1,500 of which are active United States patents. This patent portfolio of semiconductor-related inventions was developed over many years by some of the world’s leading semiconductor technology innovators, including AT&T Bell Laboratories, Lucent Technologies (Lucent), Agere Systems (Agere), LSI Logic and LSI Corporation (LSI). The portfolio reflects expertise developed at the various R&D laboratories and manufacturing locations of these companies around the world. The technology created, developed, and patented at those companies underlies many important innovations in the development of semiconductors and integrated circuits for high-tech products, including smartphones, computers, wearables, digital signal processors, IoT devices, automobiles, broadband carrier access, switches, network processors and wireless connectors. 1 Case 1:19-cv-02155-LPS Document 11 Filed 03/30/20 Page 2 of 56 PageID #: 109 2. Bell Semic was formed in 2017 to manage this portfolio of semiconductor-related intellectual property acquired from Broadcom and assigned to Bell Semic. -

Telecommunications Mergers and Acquisitions: Key Policy Issues and Options for State Regulators

NRRI97 - 20 TELECOMMUNICATIONS MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS: KEY POLICY ISSUES AND OPTIONS FOR STATE REGULATORS Edwin A. Rosenberg, Ph.D. Senior Research Specialist The National Regulatory Research Institute 1080 Carmack Road Columbus, Ohio 43210-1002 July 1997 This report was prepared by The National Regulatory Research Institute (NRRI) at the suggestion of the Illinois Commerce Commission (ICC). Funding for the research was provided by the National Association of Regulatory Utilities Commissioners (NARUC). The opinions expressed herein are the author's; no inference should be made regarding the opinions or policies of the ICC, the NRRI, the NARUC, or any member commission of the NARUC. NRRI 97-20: Telecommunications Mergers and Acquisitions TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE .......................................................... v INTRODUCTION ..................................................... 1 MARKET POWER AND MARKET STRUCTURE ............................ 4 Market Power ..................................................... 4 Competitive and Contestable Markets .................................. 4 Monopoly ......................................................... 5 Monopoly Abuses ............................................... 6 Remedies for Monopoly Abuses .................................... 8 Oligopoly . .. 9 Telecommunications Market Structures ................................ 10 MERGERS AND MARKET POWER ..................................... 12 MERGERS - GOOD AND BAD ........................................ 13 MERGERS - REGULATORY -

2003 10K Statement, Agere Systems

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on December 8, 2003 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K [X] ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended September 30, 2003 [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number 001-16397 Agere Systems Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 22-3746606 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 1110 American Parkway N.E. Allentown, Pennsylvania 18109 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: 610-712-1000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Class A Common Stock, $.01 par value New York Stock Exchange Class B Common Stock, $.01 par value New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None. Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes [X] No [ ] Indicate by check mark if disclosure of delinquent filers pursuant to Item 405 of Regulation S-K is not contained herein, and will not be contained, to the best of registrant’s knowledge, in definitive proxy or information statements incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K or any amendment to this Form 10-K. -

The Rise and Fall of Lucent Technologies

The Rise and Demise of Lucent Technologies William Lazonick The Academic-Industry Research Network and University of Massachusetts Edward March Thayer School of Engineering Dartmouth College March 2010 The original version of this paper was presented to the conference on Innovation and Competition in the Global Communications Technology Industry, INSEAD, Fontainebleau, France, August 23-24, 2007. This paper is part of a project, emanating from that conference, that is engaged in a comparative, updatable, analysis of business models and economic performance among the major competitors in the communications technology industry. For other studies generated by this project, see www.theAIRnet.org. In the later stages, funding for this paper was provided by FINNOV project through Theme 8 of the Seventh Framework Programme of the European Commission (Socio- Economic Sciences and Humanities), under the topic “The role of finance for growth, employment and competitiveness in Europe” (SSH-2007-1.2-03) as well as the Ford Foundation project on “Financial institutions for innovation and development” and the Institute for New Economic Thinking project on “The stock market and innovative enterprise”. We are grateful to Yue Zhang for research assistance. Lazonick and March: Lucent Technologies 1. From Boom to Bust to Boétie In 1999, as the Internet boom was approaching its apex, Lucent Technologies was the world’s largest telecommunications equipment company. With revenues of $38.3 billion, net income of $4.8 billion, and 153,000 employees for the fiscal year ending September 30, 1999, Lucent was larger and more profitable than Nortel, Alcatel, and Ericsson, its three major global competitors (see Figures 1 and 2).1 In fiscal 2006, however, Lucent’s revenues were only $8.8 billion and its employment level stood at 29,800. -

Some Famous Trade Marks …And the Stories Behind Them

Some famous trade marks …and the stories behind them... Like ah say, man, da shape o’ mah crittar is yooneek, so yo’ gotta defend ‘er. Yo! Dat’s da name! De Fender! Git writin‘, man, git writin‘… © Tony McStea 2013-21 18.Feb.2021 Introduction This is pure indulgence on my part. These things interest me, so I put them together in booklet form. They are arranged in the order in which I first thought of them. If anyone knows any good stories, I’d always be interested. 2 What’s where… page page page page ABC 65 Coca-Cola 3 IKEA 25 Novartis 22 AC/DC 45 Colgate 41 Intel 37 Nutella 31 Acer 62 Columbia 13 Interflora 55 Omega 16 Adidas 11 Continental 75 IWC 57 Opel 62 Adobe 54 Corn Flakes 18 J.P.Morgan Chase 67 Oreo 29 Aeroflot 73 Danone 53 Jaguar 19 Oscars 63 Agip 25 Dell 71 Jeep 49 Otis 66 AKZO Nobel 26 Delta 73 John Deere 45 Palmolive 41 Albertson’s 68 Deutsche Grammophon 42 Johnnie Walker 15 Panasonic 11 Aldi 69 DHL 46 Johnson & Johnson 35 Paramount 12 Alfa Romeo 14 Diner’s Club 47 Kenworth 45 Parker 45 Amazon 11 Dior 64 KFC 16 Patek Philippe 31 American Airlines 73 Disney 55 Kia 72 PayPal 39 American Express 47 Dow 59 KitKat 15 Penguin 43 Apple 3 Dulux 8 Kleenex 17 Pepsi-Cola 3 Araldite 40 Dunlop 65 KLM 56 Persil 18 Asda 69 Du Pont 2 Kmart 48 Peterbilt 46 Aston Martin 35 Dyson 5 2 Kodak 6 Peugeot 13 Asus 62 eBay 38 Kraft 26 PEZ 75 AT&T 32 Electrolux 58 Kroger 68 Philips 9 Audi 2 Emmys 63 Lacoste 6 Pirelli 65 Avon 20 Ericsson 63 Lamborghini 35 Porsche 2 Band-Aid 17 Esso 1 Land Rover 50 Post-It 72 Barbie 6 6 Estée Lauder 56 Lego 7 PPG 26 BASF -

Alcatel-Lucent Retirement Income Plan Lucent Pension Program Summary Plan Description December 1, 2010

Alcatel-Lucent Retirement Income Plan Lucent Pension Program Summary Plan Description December 1, 2010 Alcatel-Lucent Retirement Income Plan – Lucent Pension Program Disclaimer This is a summary of the benefits available to eligible occupational employees under the Lucent Pension Program (LPP) provisions of the Alcatel-Lucent Retirement Income Plan (Pension Plan). The LPP was created as a spinoff from the Lucent Technologies Inc. Pension Plan (LTPP), effective December 1, 2010. To the extent that this SPD refers to dates, events, agreements, elections or designations before December 1, 2010, such dates, events, agreements, elections or designations shall be recognized as if the LPP were in existence at the applicable time. Benefits for eligible occupational employees who terminated employment prior to December 1, 2010, are governed by the terms of the LTPP in effect as of their termination of employment. Occupational employees who are not represented by the Communications Workers of America or the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers and who retire on or after December 1, 2010 will be transferred from the Lucent Technologies Inc. Retirement Plan (LTRP) to the LPP. Benefits for eligible occupational employees who terminated employment on or after December 1, 2010, are governed by the terms of the LTRP in effect as of their termination of employment. This summary is provided for informational purposes only and is intended to comply with Department of Labor requirements for Summary Plan Descriptions (“SPDs”). More detailed information about the LPP is provided in the official Pension Plan document, a copy of which can be obtained by writing to the Pension Plan Administrator (see “Important Contacts” and “Other Important Information”).