Summary Rpt on Public Diplomacy at the Dept.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEPARTMENT of STATE 2201 C Street NW., Washington, DC 20520 Phone, 202–647–4000

DEPARTMENT OF STATE 2201 C Street NW., Washington, DC 20520 Phone, 202±647±4000 SECRETARY OF STATE WARREN M. CHRISTOPHER Chief of Staff THOMAS E. DONILON Executive Assistant to the Secretary ROBERT BRADTKE Special Assistant to the Secretary and KENNETH C. BRILL Executive Secretary of the Department Deputy Assistant Secretary for Equal DEIDRE A. DAVIS Employment Opportunity and Civil Rights Chief of Protocol MOLLY M. RAISER Chairman, Foreign Service Grievance Board JAMES OLDHAM Civil Service Ombudsman CATHERINE W. BROWN Deputy Secretary of State STROBE TALBOTT Under Secretary for Political Affairs PETER TARNOFF Under Secretary for Economic and JOAN E. SPERO Agricultural Affairs Under Secretary for Global Affairs TIMOTHY E. WIRTH Under Secretary for Arms Control and LYNN E. DAVIS International Security Affairs Under Secretary for Management RICHARD M. MOOSE Assistant Secretary for Administration PATRICK F. KENNEDY Assistant Secretary for Consular Affairs MARY A. RYAN Assistant Secretary for Diplomatic Security ANTHONY C.E. QUAINTON Chief Financial Officer RICHARD L. GREENE Director General of the Foreign Service and GENTA HAWKINS HOLMES Director of Personnel Medical Director, Department of State and ELMER F. RIGAMER, M.D. the Foreign Service Executive Secretary, Board of the Foreign LEWIS A. LUKENS Service Director of the Foreign Service Institute (VACANCY) Director, Office of Foreign Missions ERIC JAMES BOSWELL Assistant Secretary for Population, Refugee, PHYLLIS E. OAKLEY and Migration Affairs Inspector General JACQUELINE L. WILLIAMS-BRIDGER Director, Policy Planning Staff JAMES B. STEINBERG Assistant Secretary for Legislative Affairs WENDY RUTH SHERMAN Assistant Secretary for Democracy, Human JOHN SHATTUCK Rights and Labor Legal Adviser CONRAD K. HARPER Assistant Secretary for African Affairs GEORGE MOOSE Assistant Secretary for East Asian and Pacific WINSTON LORD Affairs Assistant Secretary for European and RICHARD HOLBROOKE Canadian Affairs Assistant Secretary for Inter-American Affairs ALEXANDER F. -

DEPARTMENT of STATE 2201 C Street NW., Washington, DC 20520 Phone, 202–647–4000

DEPARTMENT OF STATE 2201 C Street NW., Washington, DC 20520 Phone, 202±647±4000. Internet, http://www.state.gov/. SECRETARY OF STATE MADELEINE K. ALBRIGHT Chief of Staff ELAINE K. SHOCAS Executive Assistant ALEJANDRO D. WOLFF Special Assistant to the Secretary and KRISTIE A. KENNEY Executive Secretary of the Department Deputy Assistant Secretary for Equal DEIDRE A. DAVIS Employment Opportunity and Civil Rights Chief of Protocol MARY MEL FRENCH Chairman, Foreign Service Grievance Board THOMAS J. DILAURO Civil Service Ombudsman TED A. BOREK Deputy Secretary of State STROBE TALBOTT Under Secretary for Political Affairs THOMAS R. PICKERING Under Secretary for Economic, Business, and STUART E. EIZENSTAT Agricultural Affairs Under Secretary for Arms Control and JOHN D. HOLUM, Acting International Security Under Secretary for Management BONNIE R. COHEN Under Secretary for Global Affairs FRANK E. LOY Counselor of the Department of State WENDY SHERMAN Assistant Secretary for Administration PATRICK F. KENNEDY Assistant Secretary for Consular Affairs MARY A. RYAN Assistant Secretary for Diplomatic Security DAVID G. CARPENTER and Director of the Office of Foreign Missions Chief Financial Officer BERT T. EDWARDS Chief Information Officer and Director of the FERNANDO BURBANO Bureau of Information Resource Management Director General of the Foreign Service and EDWARD W. GNEHM, JR. Director of Personnel Medical Director, Department of State and CEDRIC E. DUMONT the Foreign Service Executive Secretary, Board of the Foreign TED PLOSSER Service Director of the Foreign Service Institute RUTH A. DAVIS Assistant Secretary for Population, Refugee, JULIA V. TAFT and Migration Affairs Inspector General JACQUELYN L. WILLIAMS-BRIDGERS Director, Policy Planning Staff MORTON H. -

Revolution @State: the Spread of Ediplomacy

M arch 2012 ANALYSIS FERGUS HANSON Revolution @State: Fergus is currently seconded to the Brookings Institution as a Visiting The Spread of Ediplomacy Fellow in Ediplomacy. He is also a Research Fellow and Director of Polling at the Lowy Institute. Tel: +1 202 238 3526 E xecutive summary [email protected] The US State Department has become the world’s leading user of ediplomacy. Ediplomacy now employs over 150 full-time personnel working in 25 different ediplomacy nodes at Headquarters. More than 900 people use it at US missions abroad. Ediplomacy is now used across eight different program areas at State: Knowledge Management, Public Diplomacy and Internet Freedom dominate in terms of staffing and resources. However, it is also being used for Information Management, Consular, Disaster Response, harnessing External Resources and Policy Planning. In some areas ediplomacy is changing the way State does business. In Public Diplomacy, State now operates what is effectively a global media empire, reaching a larger direct audience than the paid circulation of the ten largest US dailies and employing an army of diplomat-journalists to feed its 600-plus platforms. In other areas, like Knowledge Management, ediplomacy is finding solutions to problems that have plagued foreign ministries for centuries. The slow pace of adaptation to ediplomacy by many foreign ministries LOWY INSTITUTE FOR suggests there is a degree of uncertainty over what ediplomacy is all INTERNATIONAL POLICY about, what it can do and how pervasive its influence is going to be. 31 Bligh Street This report – the result of a four-month research project in Washington Sydney NSW 2000 DC – should help provide those answers. -

List of Delegations to the Seventieth Session of the General Assembly

UNITED NATIONS ST /SG/SER.C/L.624 _____________________________________________________________________________ Secretariat Distr.: Limited 18 December 2015 PROTOCOL AND LIAISON SERVICE LIST OF DELEGATIONS TO THE SEVENTIETH SESSION OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY I. MEMBER STATES Page Page Afghanistan......................................................................... 5 Chile ................................................................................. 47 Albania ............................................................................... 6 China ................................................................................ 49 Algeria ................................................................................ 7 Colombia .......................................................................... 50 Andorra ............................................................................... 8 Comoros ........................................................................... 51 Angola ................................................................................ 9 Congo ............................................................................... 52 Antigua and Barbuda ........................................................ 11 Costa Rica ........................................................................ 53 Argentina .......................................................................... 12 Côte d’Ivoire .................................................................... 54 Armenia ........................................................................... -

Telephone Directory

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Organizational Directory 5/2/2011 Provided by The Office of Global Publishing Solutions, A/ISS/GPS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Organizational Directory United States Department of State 2201 C Street NW, Washington, DC 20520 Office of the Secretary (S) Editor Editor 7516 202-647-1512 The Watch 7516 202-647-1512 Secretary Crisis Management Staff 7516 202-647-7640 Secretary Hillary Clinton 7th Floor 202-647-5291 Emergency and Evacuations Planning 7516 202-647-7640 Office Manager Claire Coleman 7226 202-647-7098 Emergency Relocation 7516 202-647-7640 Counselor and Chief of Staff Cheryl Mills 7226 202-647-5548 Military Representative Lt. Col. Paul Matier 7516 202-647-6097 Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations Huma Abedin 202-647-9572 7226 Office of the Executive Director (S/ES-EX) Deputy Chief of Staff for Policy Jacob Sullivan 7226 202-647-9572 Scheduling Lona Valmoro 7226 202-647-9071 Executive Director, Deputy Executive Secretary 202-647-7457 Lewis A. Lukens 7507 Scheduling Linda Dewan 7226 202-647-5733 Deputy Executive Director Mark R. Brandt 7507 202-647-5467 Executive Assistant Joseph Macmanus 7226 202-647-9572 Personnel Officer Cynthia J. Motley 7515 202-647-5638 Special Assistant Laura Lucas 7226 202-647-9573 Budget Officer Reginald J. Green 7515 202-647-9794 Special Assistant Timmy T. Davis 7226 202-647-6822 General Services Officer Dwayne Cline 7519 202-647-9221 Staff Assistant Lauren Jiloty 7226 202-647-5298 Staff Assistant Daniel Fogarty 7226 202-647-9572 Ombudsman for Civil Service Employees (S/CSO) Executive Secretariat (S/ES) Ombudsman Shireen Dodson 7428 202-647-9387 Special Assistant to the Secretary and the Executive 202-647-5301 Secretary of the Department Stephen D. -

Telephone Directory

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Organizational Directory 1/19/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Organizational Directory United States Department of State 2201 C Street NW, Washington, DC 20520 Office of the Secretary (S) Emergency and Evacuations Planning CMS Staff 202-647-7640 7516 Secretary Emergency Relocation CMS Staff 7516 202-647-7640 Secretary Michael R Pompeo 7th Floor 202-647-4000 Resident task force ONLY Task Force 1 7516 202-647-6611 Executive Assistant Timmy T Davis 7226 202-647-4000 Consular task force ONLY Task Force 2 (CA) 7516 202-647-7004 Special Assistant Andrew Lederman 7226 202-647-4000 Resident task force ONLY Task Force 3 7516 202-647-6613 Special Assistant Kathryn L Donnell 7226 202-647-4000 Special Assistant Jeffrey H Sillin 7226 202-647-4000 Office of the Executive Director (S/ES-EX) Special Assistant Victoria Ellington 7226 202-647-4000 Executive Director, Deputy Executive Secretary 202-647-7457 Scheduling & Advance Joseph G Semrad 7226 202-647-4000 Howard VanVranken 7507 Scheduler Ruth Fisher 7226 202-647-4000 Deputy Executive Director Michelle Ward 7507 202-647-5475 Office Manager Sally Ritchie 7226 202-647-4000 Budget Officer Reginald J. Green 7515 202-647-9794 Office Manager Hillaire Campbell 7226 202-647-4000 Bureau Security Officer Dave Shamber 5634 202-647-7478 Senior Advisor Mary Kissel 7242 202-647-4000 Human Resources Division Director Eboni C 202-647-5478 Staff Asst. to SA Kissel Simonette -

The Foreign Service Journal, October 2006.Pdf

AFSA SCORES CONGRESS REACHING OUT TO MUSLIMS TWO RIVERS $3.50 / OCTOBER 2006 OREIGN ERVICE FJ O U R N A L S THE MAGAZINE FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS PROFESSIONALS BRANDISHING THE BULLHORN Public Diplomacy Under Karen Hughes CONTENTS October 2006 Volume 83, No. 10 F OCUS ON P UBLIC D IPLOMACY F EATURE 19 / DAMAGE CONTROL: KEEPING SCORE IN THE CONGRESSIONAL GAME / 53 KAREN HUGHES DOES PD AFSA profiles how your senators and representatives A year into her tenure, is supported American engagement in world affairs. Hughes making effective use By Ken Nakamura of Foreign Service expertise? By Shawn Zeller 27 / PUBLIC DIPLOMACY C OLUMNS D EPARTMENTS MATTERS MORE THAN EVER PRESIDENT’S VIEWS / 5 Like intelligence analysis, LETTERS / 6 Ideology, Greed and the PD must be protected from CYBERNOTES / 10 Future of the Foreign Service MARKETPLACE / 12 political strong-arming, By J. Anthony Holmes AFSA NEWS / 71 generously funded and BOOKS / 83 PEAKING UT heeded at the highest level. S O / 14 IN MEMORY / 87 By Patricia H. Kushlis and Reaching Out to Muslims INDEX TO Patricia L. Sharpe By Richard S. Sacks ADVERTISERS / 98 33 / NEITHER MADISON AVENUE NOR HOLLYWOOD REFLECTIONS / 100 If public diplomacy has failed, as many critics Two Rivers Run Through It now claim, it is not due to an inability to find By Scott R. Riedmann the secret slogan or magic message. By Robert J. Callahan 39 / REBUILDING AMERICA’S CULTURAL DIPLOMACY Since the end of the Cold War, the U.S. has unwisely left cultural and educational diplomacy to the tough mercies of the marketplace. -

The US Department of State Student Internship Program

E PL UR U M I B N U U S 13-23026 Student Internship_COVER.indd 1 6/4/13 7:50 AM The U.S. Department of State Student Internship Program The U.S. Department of State The U.S. Department of State is the leading U.S. foreign affairs agency responsible for advancing freedom for the benefit of the American people and the international community. The Department’s employees, Foreign Service Officers and Specialists, Civil Service professionals and Foreign Service Nationals work at over 265 locations overseas, and throughout the United States. Together, they help to build and sustain a more democratic, secure, and prosperous world composed of well-governed states that respond to the needs of their people, reduce widespread poverty, and act responsibly within the international system. The Department selects and hires employees who can accomplish America’s mission of diplomacy at home and around the world, including Foreign Service Officers (FSO), Foreign Service Specialists (FSS) and Civil Service (CS) professionals. For those pursuing undergraduate, graduate or other advanced degrees, and professionals who are interested in an executive development program in public service, the Department offers a number of internships and fellowships. The U.S. Department of State’s Mission Shape and sustain a peaceful, prosperous, just, and democratic world and foster conditions for stability and progress for the benefit of the American people and people everywhere. U.S. Department of State Structure The U.S. Department of State is made up of bureaus with responsibility for the many aspects of U.S. foreign policy and the general operations and administration of our diplomatic missions abroad. -

Department of State Telephone Directory

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Organizational Directory 1/25/2017 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Organizational Directory United States Department of State 2201 C Street NW, Washington, DC 20520 Office of the Secretary (S) Lucia Piazza 7516 (24 Hour Per Day) Senior Watch Officer 7516 202-647-1512 Secretary Military Representative Col Francisco Gallei 7516 202-647-6097 Secretary John Kerry 7th Floor 202-647-9572 (24 Hours Per Day) Editor 7516 202-647-1512 Chief of Staff Jonathan J. Finer 7234 202-647-8633 (24 Hours Per Day) The Watch 7516 202-647-1512 Deputy Chief of Staff Jennifer Stout 7226 202-647-5548 CMS Crisis Management Support 7516 202-647-7640 Deputy Chief of Staff Thomas Sullivan 7226 202-647-9071 Emergency and Evacuations Planning CMS Staff 202-647-7640 Executive Assistant Lisa Kenna 7226 202-647-9572 7516 Office Manager Claire L. Coleman 7226 202-647-9572 Emergency Relocation CMS Staff 7516 202-647-7640 Senior Aide Jason Meininger 7226 202-647-5601 Resident task force ONLY Task Force 1 7516 202-647-6611 Scheduling Julie Ann Wirkkala 7226 202-647-5733 Consular task force ONLY Task Force 2 (CA) 7516 202-647-6612 Scheduling John Natter 7226 202-647-5733 Resident task force ONLY Task Force 3 7516 202-647-6613 Senior Advisor Cindy Chang 7226 202-647-9572 Special Assistant William P. Cobb 7226 202-647-9572 Office of the Executive Director (S/ES-EX) Special Assistant Sujata Sharma 7226 202-647-9572 Executive Director, Deputy Executive Secretary Eric 202-647-7457 Special Assistant Christopher Flanagan 7226 202-647-9572 Nelson 7507 Special Assistant Nicholas Christensen 7226 202-647-9572 Deputy Executive Director Jonathan R. -

DEPARTMENT of STATE 2201 C Street NW., Washington, DC 20520 Phone, 202–647–4000

DEPARTMENT OF STATE 2201 C Street NW., Washington, DC 20520 Phone, 202±647±4000. Internet, http://www.state.gov/. SECRETARY OF STATE MADELEINE K. ALBRIGHT Chief of Staff ELAINE K. SHOCAS Executive Assistant DAVID M. HALE Special Assistant to the Secretary and KRISTIE A. KENNEY Executive Secretary of the Department Deputy Assistant Secretary for Equal DEIDRE A. DAVIS Employment Opportunity and Civil Rights Chief of Protocol MARY MEL FRENCH Chairman, Foreign Service Grievance Board THOMAS J. DILAURO Civil Service Ombudsman TED A. BOREK Deputy Secretary of State STROBE TALBOTT Under Secretary for Political Affairs THOMAS R. PICKERING Under Secretary for Economic, Business, and STUART E. EIZENSTAT Agricultural Affairs Under Secretary for Arms Control and JOHN HOLUM, Acting International Security Affairs Under Secretary for Management BONNIE R. COHEN Under Secretary for Global Affairs WENDY SHERMAN, Acting Counselor of the Department of State WENDY SHERMAN Assistant Secretary for Administration PATRICK R. HAYES, Acting Assistant Secretary for Consular Affairs MARY A. RYAN Assistant Secretary for Diplomatic Security PATRICK F. KENNEDY, Acting Chief Financial Officer RICHARD L. GREENE Director General of the Foreign Service and EDWARD W. GNEHM, Acting Director of Personnel Medical Director, Department of State and CEDRIC E. DUMONT the Foreign Service Executive Secretary, Board of the Foreign JONATHAN MUDGE Service Director of the Foreign Service Institute RUTH A. DAVIS Director, Office of Foreign Missions PATRICK F. KENNEDY, Acting Assistant Secretary for Population, Refugee, JULIA V. TAFT and Migration Affairs Inspector General JACQUELINE L. WILLIAMS-BRIDGER Director, Policy Planning Staff GREGORY P. CRAIG Assistant Secretary for Legislative Affairs BARBARA LARKIN Assistant Secretary for Democracy, Human JOHN SHATTUCK Rights, and Labor Legal Advisor DAVID R. -

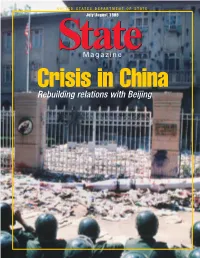

Rebuilding Relations with Beijing Coming in September: Thessaloniki

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF STATE July/August 1999 StateStateMagazine Crisis in China Rebuilding relations with Beijing Coming in September: Thessaloniki State Magazine (ISSN 1099–4165) is published monthly, except bimonthly in July and August, by the U.S. Department of State, 2201 C St., N.W., Washington, DC. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, State DC. POSTMASTER: Send changes of address to State Magazine, Magazine PER/ER/SMG, SA-6, Room 433, Washington, DC 20522-0602. State Carl Goodman Magazine is published to facilitate communication between manage- ment and employees at home and abroad and to acquaint employees EDITOR-IN-CHIEF with developments that may affect operations or personnel. The Donna Miles magazine is also available to persons interested in working for the DEPUTY EDITOR Department of State and to the general public. Kathleen Goldynia State Magazine is available by subscription through the DESIGNER Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Isaias Alba IV Washington, DC 20402 (telephone [202] 512-1850). The magazine can EDITORIAL ASSISTANT be viewed online free at www.state.gov/www/publications/statemag. The magazine welcomes State-related news and features. Informal ADVISORY BOARD MEMBERS articles work best, accompanied by photographs. Staff is unable to James Williams acknowledge every submission or make a commitment as to which CHAIRMAN issue it will appear in. Photographs will be returned upon request. Articles should not exceed five typewritten, double-spaced Sally Light pages. They should also be free of acronyms (with all office names, EXECUTIVE SECRETARY agencies and organizations spelled out). Photos should include Albert Curley typed captions identifying persons from left to right with job titles. -

DEPARTMENT of STATE 2201 C Street NW., Washington, DC 20520 Phone, 202–647–4000

DEPARTMENT OF STATE 2201 C Street NW., Washington, DC 20520 Phone, 202±647±4000. Internet, www.state.gov. SECRETARY OF STATE MADELEINE K. ALBRIGHT Assistant Secretary for Intelligence and J. STAPLETON ROY Research Assistant Secretary for Legislative Affairs BARBARA LARKIN Chairman, Foreign Service Grievance Board EDWARD REIDY Chief of Protocol MARY MEL FRENCH Chief of Staff ELAINE K. SHOCAS Civil Service Ombudsman TED A. BOREK Counselor of the Department of State WENDY SHERMAN Deputy Assistant Secretary for Equal DEIDRE A. DAVIS Employment Opportunity and Civil Rights Director, Policy Planning Staff MORTON H. HALPERIN Inspector General JACQUELYN L. WILLIAMS-BRIDGERS Legal Advisor DAVID R. ANDREWS Special Assistant to the Secretary and KRISTIE A. KENNEY Executive Secretary of the Department Deputy Secretary of State STROBE TALBOTT Under Secretary for Arms Control and JOHN D. HOLUM, Acting International Security Affairs Assistant Secretary for Arms Control AVIS T. BOHLEN Assistant Secretary for Nonproliferation ROBERT J. EINHORN Assistant Secretary for Political-Military ERIC NEWSOM Affairs Assistant Secretary for Verification and (VACANCY) Compliance Under Secretary for Economic, Business, and ALAN P. LARSON Agricultural Affairs Assistant Secretary for Economic and EARL ANTHONY WAYNE Business Affairs Under Secretary for Global Affairs FRANK E. LOY Assistant Secretary for Democracy, Human HAROLD H. KOH Rights, and Labor Assistant Secretary for International RAND BEERS Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs Assistant Secretary for Oceans and DAVID B. SANDALOW International Environmental and Scientific Affairs Assistant Secretary for Population, JULIA V. TAFT Refugee, and Migration Affairs Under Secretary for Management BONNIE R. COHEN Assistant Secretary for Administration PATRICK F. KENNEDY Assistant Secretary for Consular Affairs MARY A.