2006 Founder's Day Video Series Script

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alumni Magazine UMMER 2007 S • 1 ER NUMB • 8 UME VOL

IllinoisIllinois StateState alumni magazine UMMER 2007 S • 1 ER NUMB • 8 UME VOL Making music and memories with the Big Red Marching Machine. page 24 Marching through time It takes hard work practicing in the heat, followed by pain as performances are played in freezing temperatures. And yet members of The Big Red Marching Machine will attest that there is no sweeter experience than the years spent making music in the University’s marching band. Cover: Illinois State band members have played with 11 pride for decades. Contents 2 UNIVERSITY NEWS 8 DELAYED BUT NOT DEFEATED Lisa Daniels ’99, M.S. ’00, watched her classmates head off to college after high school. As a teenage mom, she wasn’t able to follow the traditional academic path. Daniels was 29 when she arrived at Illinois State. Now part of an international firm, she empowers struggling students with her success story. 8 16 I STHE EARTH WARMING? Geography-Geology Professor Emeritus James Carter answers the 16 question debated by so many experts that the general public is left to ponder the need for panic. Carter’s examination of inevitable climate change provides insights into what’s happening across the planet. 20 TACKLING THE NATION’S ILLS Chris Wiant ’72 is immersed in two of the country’s toughest problems—health care woes and environmental safety concerns. Now the CEO of a $170 million foundation dedicated to improving Colorado’s health care, Wiant is lauded nationally as the man who negotiated the Rocky Mountain Arsenal clean-up. 24 DAYS LESS GLORIOUS While most remember their collegiate years as carefree and grand, wars, civil unrest, and economic downturns left their mark on the campus community. -

Illinois STATE, November 2018

From war to warrior Colonel takes on the fight to help fellow veterans heal invisible wounds to their soul and spirit. NOVEMBER 2018 NOVEMBER • NUMBER 3 NUMBER • 19 VOLUME RedbirdsRising.IllinoisState.edu EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Susan Marquardt Blystone ’84, M.S. ’03 ALUMNI EDITOR Rachel Kobus ’09, M.S. ’11 LEAD DESIGNERS First Word Dave Jorgensen, M.S. ’03 Michael Mahle The holiday season is once again fast approaching, DESIGNERS resulting in a time of reflection as the calendar year comes to a close. As Illinois State Jeff Higgerson ’92 Sean Thornton ’00, M.S. ’17 University’s president, my thoughts inevitably turn to all that has been achieved within Evan Walles ’06 the campus community. WEB EDITOR There is the fact that ISU’s enrollment is strong and stable at a time when many Kevin Bersett, MBA ’17 PHOTOGRAPHER public institutions are struggling. Our student body this fall totals 20,635 giving credence Lyndsie Schlink ’04 to the claim that Illinois State remains a top-choice institution. PRODUCTION COORDINATOR Financial support for the University is gratifying and humbling, as donors have con- Tracy Widergren ’03, M.S. ’15 WRITERS tributed more than $124 million toward the $150 million Kate Arthur Redbirds Rising campaign goal. There is no doubt the Kevin Bersett, MBA ’17 John Moody objectives of strengthening scholarship, leadership, and innovation will be achieved through the fundraising Illinois State (USPS 019606) is published four times annually for donors and members of the Illinois State effort that ends in 2020. University Alumni Association at Alumni Center, 1101 N. Main Street, Normal, Illinois 61790-3100. -

Jungle Classroom Biology Students’ Quest for Learning Leads to Costa Rican Adventure EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Susan Marquardt Blystone ’84, M.S

VOLUME 14 • NUMBER 4• MAY 2014 Jungle classroom Jungle leads to Costa Ricanadventure leads toCosta forlearning quest Biology students’ EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Susan Marquardt Blystone ’84, M.S. ’03 ALUMNI EDITOR Zach Parcell ’08 COPY EDITOR Kevin Bersett LEAD DESIGNERS FirstWord Dave Jorgensen, M.S. ’03 Michael Mahle Four years to finish a degree seemed like an eternity DESIGNERS to me when I arrived at Illinois State as a freshman. The thought of navigating through Jeff Higgerson ’92 all the classes, papers, and projects on the journey between the first and final semester Carol Jalowiec ’08 Jon Robinson M.S. ’12 was overwhelming. WEB EDITOR So were the goodbyes at move-in. I vividly remember watching as my parents pulled Ryan Denham away from the curb that hot August evening in 1980. The car had been emptied of all my PHOTOGRAPHER Lyndsie Schlink ’04 belongings. They were heading home with nothing but memories to fill what had been PRODUCTION COORDINATOR my spot in the backseat. Tracy Widergren ’03 Colby 1079 was my new home, a WRITERS Steven Barcus ’06, M.S. ’09 fact that seemed surreal as I walked to Kevin Bersett Ryan Denham the elevator and hit the button for what Tom Nugent my floormates affectionately called ‘the EDITORIAL INTERN penthouse.’ Kelsey Lutz That first evening was filled with Illinois State (USPS 019606) is published quarterly for members of the Illinois State University Alumni introductions, nervous laughter, pizza Association at Alumni Center, 1101 N. Main Street, from Garcia’s, and a sense of camarade- Normal, Illinois 61790-3100. Periodicals postage paid at Normal, Illinois, and at additional mailing offices. -

Alumni Magazine 0 0 9 2 L L FA • N U M B E R 2 • V O L U M E 1 0

V o l u m e 1 0 • N u m b e r 2 • FA l l 2 0 0 9 Illinois State students. current generation of is the norm for the Digital communication Illinois State Illinois alumni magazine illinois state alumni magazine Volume 10, Number 2, Fall 2009 Editorial advisory GROUP Pete Guither; Amy Humphreys; Joy Hutchcraft; Lynn Kennell; Katy Killian ’92; Todd Kober ’97, M.S. ’99; Claire Lieberman; Marilee (Zielinski) Rapp ’63; Jim Thompson ’80, M.S. ’89; Toni Tucker; Lori Woeste, M.S. ’97, Ed.D. ’04 PUblishEr, Stephanie Epp, Ed.D. ’07 Editor-in-chiEf, Susan Marquardt Blystone ’84, M.S. ’03 alUmni Editor, Annette States Levitt ’96, M.S. ’02 class notEs Editor, Janae Stork coPy Editors, Susan Marquardt Blystone ’84, M.S. ’03; Steven Barcus ’06 lEad DesiGnEr, Dave Jorgensen, M.S. ’03 DesiGnErs, Jeff Higgerson ’92, Brian Huonker ’92, Carol Jalowiec ’08, Michael Mahle, Jon Robinson The First PHOTOGRAPhEr, Lyndsie Schlink ’04 PROdUCTION coordinator, Mary (Mulhall) Cowdery ’80 Word writErs, Kate Arthur, Steven Barcus ’06, Phaedra Hise, Megan Murray ’09 Illinois State (USPS 019606) is published quarterly for members of the there are many unsung heroes at illinois state. Illinois State University Alumni Association at Bone Student Center 146, Included among them are employees who quietly exceed all expectations, 100 North University Street, Normal, Illinois 61790-3100. Periodicals consistently giving an extraordinary effort to make certain students realize postage paid at Normal, Illinois, and at additional mailing offices. Magazine editorial offices are located at 1101 North Main Street, Normal, they are valued members of the University family. -

Illinois State Magazine, November 2018 Issue University Marketing and Communications

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Illinois State Magazine University Marketing and Communications 11-1-2018 Illinois State Magazine, November 2018 Issue University Marketing and Communications Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/ism Recommended Citation University Marketing and Communications, "Illinois State Magazine, November 2018 Issue" (2018). Illinois State Magazine. 39. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/ism/39 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Marketing and Communications at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Illinois State Magazine by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From war to warrior Colonel takes on the fight to help fellow veterans heal invisible wounds to their soul and spirit. NOVEMBER 2018 NOVEMBER • NUMBER 3 NUMBER • 19 VOLUME RedbirdsRising.IllinoisState.edu EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Susan Marquardt Blystone ’84, M.S. ’03 ALUMNI EDITOR Rachel Kobus ’09, M.S. ’11 LEAD DESIGNERS First Word Dave Jorgensen, M.S. ’03 Michael Mahle The holiday season is once again fast approaching, DESIGNERS resulting in a time of reflection as the calendar year comes to a close. As Illinois State Jeff Higgerson ’92 Sean Thornton ’00, M.S. ’17 University’s president, my thoughts inevitably turn to all that has been achieved within Evan Walles ’06 the campus community. WEB EDITOR There is the fact that ISU’s enrollment is strong and stable at a time when many Kevin Bersett, MBA ’17 PHOTOGRAPHER public institutions are struggling. Our student body this fall totals 20,635 giving credence Lyndsie Schlink ’04 to the claim that Illinois State remains a top-choice institution. -

Illinois State Volleyball

Illinois State VolleybalL 2021 spring Match notes MVC Tournament at Redbird Arena Normal, Illinois 2021 Illinois State Spring Schedule SCOUTING THE BRACKET (13-5 Overall, 11-3 MVC) No. 8 Indiana State No. 4 Bradley No. 5 Valparaiso January 22 at No. 20 Marquette L, 0-3 23 at No. 20 Marquette W, 3-2 25 Bradley * W, 3-0 29 (RV) Cincinnati L, 1-3 30 (RV) Cincinnati W, 3-0 2021 Record: 7-12, 7-11 MVC 2021 Record: 12-6, 12-6 MVC 2021 Record: 11-9, 10-8 MVC 2019 Overall Record: 7-21 2019 Overall Record: 15-15 2019 Overall Record: 14-20 February 2019 NCAA Postseason: n/a 2019 NCAA Postseason: n/a 2019 NCAA Postseason: n/a 1 at Bradley * L, 0-3 Head Coach: Lindsay Allman Head Coach: Carol Price-Torok Head Coach: Carin Avery 7 at Indiana State * W, 3-2 Career Record: 35-74 Career Record: 68-74 Career DI Record: 423-207 8 at Indiana State * L, 1-3 Record at INS: same Record at BU: same Record at VU: same Series: Illinois State leads 66-9 Series: Illinois State leads 59-12 Series: Illinois State leads 10-3 14 Drake * W, 3-0 Last Meeting: 2/8/21 (INS won 1-3) Last Meeting: 2/1/21 (BU won 3-0) Last Meeting: 2/22/21 (VU won 3-2) 15 Drake * W, 3-1 2021 Illinois State Spring Roster 21 Valparaiso * W, 3-1 No. Name Pos. Yr. Ht. Hometown / Last School(s) 22 Valparaiso * L, 2-3 1 Jessica D’Ambrose L Fr. -

Illinois State's Response

Nov. 2013 COVER.indd 1 VOLUME 14 • NUMBER 2 • NOVEMBER 2013 9/30/13 10:55AM EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Susan Marquardt Blystone ’84, M.S. ’03 ALUMNI EDITOR Zach Parcell ’08 COPY EDITOR Kevin Bersett LEAD DESIGNERS FirstWord Dave Jorgensen, M.S. ’03 Michael Mahle From the moment Nancy and I arrived on campus DESIGNERS August 8, we have been impressed by the warm and welcoming attitude of everyone Jeff Higgerson ’92 Carol Jalowiec ’08 we have encountered in the campus and local community. We enjoyed meeting faculty, Jon Robinson M.S. ’12 staff members, students, alumni and retirees. We assisted students as they moved in to Sean Thornton ’00 residence halls and apartments, and enjoyed a cookout with student-athletes. In every WEB EDITOR Ryan Denham instance, we felt the genuine excitement that greets the new academic year. PHOTOGRAPHER The fall semester began with on-campus enrollment slightly lower than last year. Lyndsie Schlink ’04 New numbers show more students are taking PRODUCTION COORDinatOR Tracy Widergren ’03 classes at off-campus locations in Chicago and WRITERS downstate Illinois. Steven Barcus ’06, M.S. ’09 Kevin Bersett The academic quality of our students is on Ryan Denham the rise, with ACT and grade point averages well EDITORIAL INTERN Brooke Burns ’10 above national averages and among the highest in the state. Illinois State (USPS 019606) is published quarterly for members of the Illinois State University Alumni The numbers and academic quality of stu- Association at Alumni Center, 1101 N. Main Street, Normal, Illinois 61790-3100. Periodicals postage paid dents from underrepresented groups continues at Normal, Illinois, and at additional mailing offices. -

Digital Brochure

OUR STUDENTS FALL IN LOVE WITH ILLINOIS STATE FROM THEIR FIRST STEPS ON CAMPUS. Insider Tip We’ve included insider tips throughout this book It’s a hard feeling to put a finger on, but as you flip to help you find that special feeling. through these pages considering where your path might lead, we’ll offer a taste of what it’s like to be a Redbird. And who knows? You may just fall in love with Illinois State too. Illinois State ranks among the Top 100 best national YOUR OPTIONS public universities based on Find a program at Illinois State and start creating your future. academic quality and student AGRICULTURE AND Music – New Media Composition Biological Sciences Teacher Education HUMANITIES AND LANGUAGE Conservation Biology Music – Voice Performance Business Teacher Education Engineering Physics success, according to U.S. ENVIRONMENT English – Creative Writing Music Business Chemistry Teacher Education Environmental Systems Science and Agribusiness English – Publishing Studies Music Therapy Dance Teacher Education Sustainability News & World Report. Agriculture Communications and Lead- English – Technical Writing and Rhet- Exercise Science – Allied Health Profes- ership Organizational Leadership and Commu- Deaf and Hard of Hearing Education orics nication sions Agronomy Management Early Childhood Education English Political Communication Exercise Science – Health and Human Animal Industry Management Earth and Space Science Teacher European Studies Performance Public Relations Education Animal Science French Geography Radio Elementary -

Alumni Magazine Winter 2009-2010 • N U M B E R 3 •

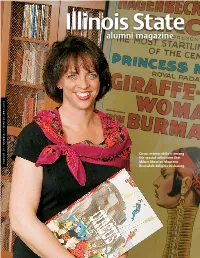

Illinois State alumni magazine WINTer 2009-2010 • N u m b e r 3 • Circus memorabilia is among the special collections that Milner librarian Maureen V o l u m e 1 0 Brunsdale delights in sharing. illinois state alumni magazine Volume 10, Number 3, Winter 2009-2010 Editorial advisory GROUP Pete Guither; Amy Humphreys; Joy Hutchcraft; Lynn Kennell; Katy Killian ’92; Todd Kober ’97, M.S. ’99; Claire Lieberman; Marilee (Zielinski) Rapp ’63; Jim Thompson ’80, M.S. ’89; Toni Tucker; Lori Woeste, M.S. ’97, Ed.D. ’04 PUblishEr, Stephanie Epp, Ed.D. ’07 Editor-in-chiEf, Susan Marquardt Blystone ’84, M.S. ’03 alUmni Editor, Annette States Levitt ’96, M.S. ’02 class notEs Editor, Janae Stork coPy Editors, Susan Marquardt Blystone ’84, M.S. ’03; Steven Barcus ’06 lEad DesiGnEr, Dave Jorgensen, M.S. ’03 DesiGnErs, Jeff Higgerson ’92, Brian Huonker ’92, Carol Jalowiec ’08, Michael Mahle, Jon Robinson The First PHOTOGRAPhEr, Lyndsie Schlink ’04 PROdUCTION coordinator, Mary (Mulhall) Cowdery ’80 Word writErs, Kate Arthur, Megan Murray ’09 Illinois State (USPS 019606) is published quarterly for members of the Illinois State University Alumni Association at Bone Student Center 146, rarely does a day pass without 100 North University Street, Normal, Illinois 61790-3100. Periodicals some national news on the education front. Media report the pitfalls postage paid at Normal, Illinois, and at additional mailing offices. Magazine editorial offices are located at 1101 North Main Street, Normal, and progress within schools across the country, creating a steady flow of Illinois 61790-3100; telephone (309) 438-2586; facsimile (309) 438-8057; headlines that seem to focus disproportionately on the negative. -

The Shots Seen Around the World February 2012 February Number 3 • Number • Volume 12 Publisher Stephanie Epp Bernoteit, Ed.D

VOLUME 12 • NUMBER 3• FEBRUARY 2012 The shotsseen the world around around PUBLISHER Stephanie Epp Bernoteit, Ed.D. ’07 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF FirstWord Susan Marquardt Blystone ’84, M.S. ’03 ALUMNI EDITOR The nation’s economic struggles are impossible to ignore, Annette States Vaughan ’96, M.S. ’02 as media reports keep news of unemployment rates and Wall Street woes on our minds CLASS NOTES EDITOR Nancy Neisler daily. While discouraging headlines and gloomy predictions trouble all adults, they COPY EDITORS cripple our college students. Susan Marquardt Blystone ’84, M.S. ’03 Steven Barcus ’06, M.S. ’09 I have never encountered so many students still in the process of completing LEAD DESIGNER their degree who are simultane- Dave Jorgensen, M.S. ’03 ously in a state of angst regarding DESIGNERS Jeff Higgerson ’92 their future employment. Their Carol Jalowiec ’08 Michael Mahle concern is legitimate given jobs Jon Robinson are disappearing, which creates a WEB EDITOR stress level unlike what graduates Brian Huonker ’92 of years past experienced. PHOTOGRAPHER Lyndsie Schlink ’04 Illinois State’s faculty and PRODUCTION COORDINATOR staff are responding in several Mary (Mulhall) Cowdery ’80 ways to empower our students to WRITERS Kate Arthur go forward with confidence. The first priority remains as it has since the University’s Steven Barcus ’06, M.S. ’09 founding in 1857: We provide a solid educational experience that allows students to EDITORIAL INTERNS Lyndsey Eagle mature academically, personally, and professionally. Kristen Wegrzyn Evidence that this goal is being met exists across campus. Mennonite College of Illinois State (USPS 019606) is published quarterly for members of the Illinois State University Alumni Nursing graduates consistently exceed state and national averages on the professional Association at Alumni Center, 1101 N. -

Illinois State Magazine, May 2014 Issue University Marketing and Communications

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Illinois State Magazine University Marketing and Communications 5-1-2014 Illinois State Magazine, May 2014 Issue University Marketing and Communications Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/ism Recommended Citation University Marketing and Communications, "Illinois State Magazine, May 2014 Issue" (2014). Illinois State Magazine. 22. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/ism/22 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Marketing and Communications at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Illinois State Magazine by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 14 • NUMBER 4• MAY 2014 Jungle classroom Jungle leads to Costa Ricanadventure leads toCosta forlearning quest Biology students’ EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Susan Marquardt Blystone ’84, M.S. ’03 ALUMNI EDITOR Zach Parcell ’08 COPY EDITOR Kevin Bersett LEAD DESIGNERS FirstWord Dave Jorgensen, M.S. ’03 Michael Mahle Four years to finish a degree seemed like an eternity DESIGNERS to me when I arrived at Illinois State as a freshman. The thought of navigating through Jeff Higgerson ’92 all the classes, papers, and projects on the journey between the first and final semester Carol Jalowiec ’08 Jon Robinson M.S. ’12 was overwhelming. WEB EDITOR So were the goodbyes at move-in. I vividly remember watching as my parents pulled Ryan Denham away from the curb that hot August evening in 1980. The car had been emptied of all my PHOTOGRAPHER Lyndsie Schlink ’04 belongings. -

Illinois State Magazine, May 2015 Issue University Marketing and Communications

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Illinois State Magazine University Marketing and Communications 5-1-2015 Illinois State Magazine, May 2015 Issue University Marketing and Communications Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/ism Recommended Citation University Marketing and Communications, "Illinois State Magazine, May 2015 Issue" (2015). Illinois State Magazine. 26. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/ism/26 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Marketing and Communications at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Illinois State Magazine by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 15 • NUMBER 4• MAY 2015 have elevated Redbird football. Redbird elevated have planandpatience Spack’s Brock the Coach to Kudos EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Susan Marquardt Blystone ’84, M.S. ’03 ALUMNI EDITOR Zach Parcell ’08 COPY EDITOR Kevin Bersett LEAD DESIGNERS FirstWord Dave Jorgensen, M.S. ’03 Michael Mahle As I reflect on my first full academic year DESIGNERS as Illinois State University’s 19th president, I recall one of my first days on the job and Jeff Higgerson ’92 Sean Thornton ’00 an interview with a reporter from our student newspaper, the Vidette. The reporter Carol (Jalowiec) Watson ’08 remarked that I had ascended to the presidency rapidly, having been appointed after WEB EDITOR Ryan Denham serving less than three years as vice president for Student Affairs. PHOTOGRAPHER For a moment, I felt like a very young man again. Lyndsie Schlink ’04 That was, until I had to confess I have actually served PRODUCTION COORDINATOR Tracy Widergren ’03 in public higher education for more than four decades WRITERS in many different roles and at several institutions.